The Chicago-based artist on growing up in Iraq during the war and how his paintings endangered his life — and led to international acclaim.

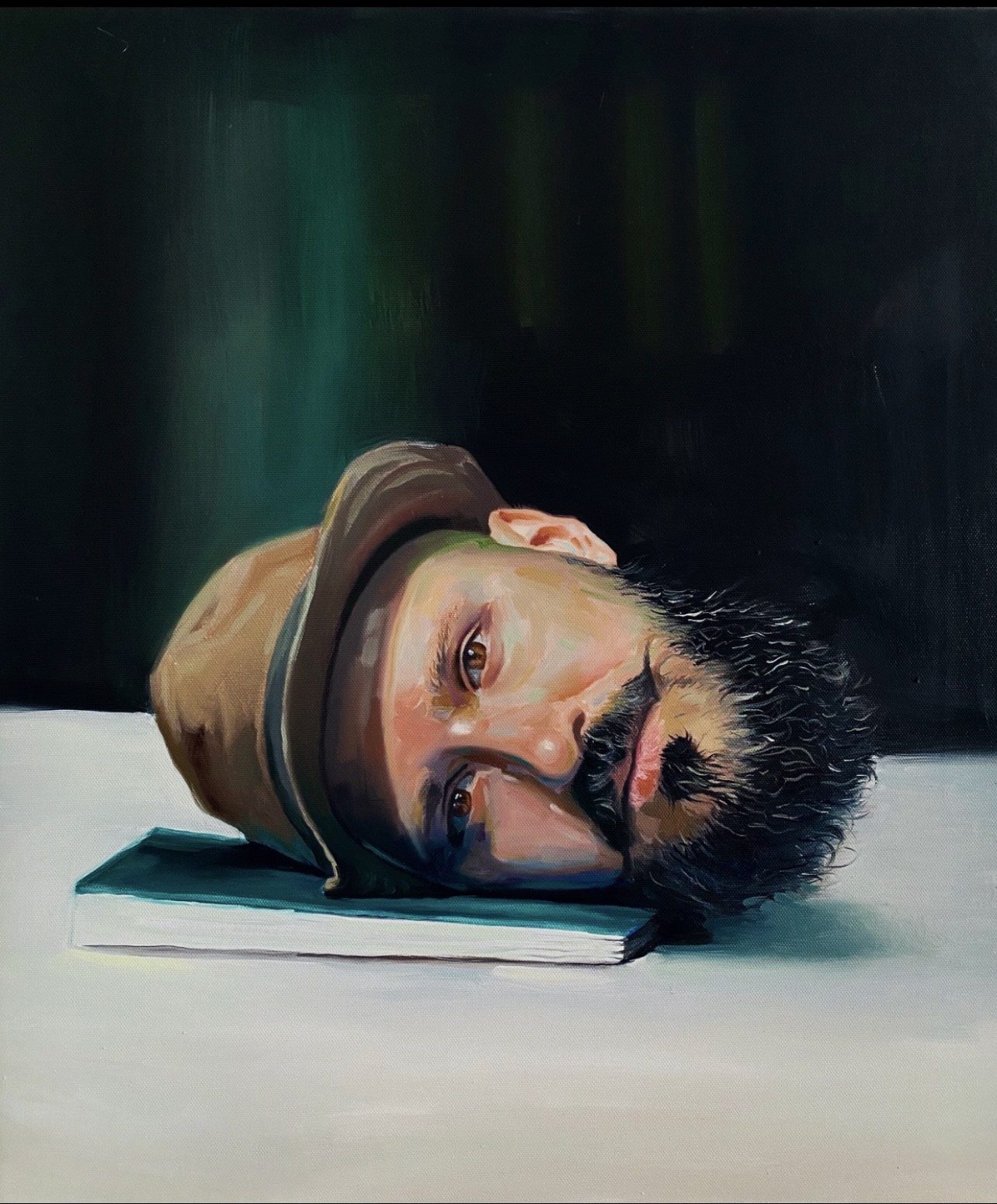

Bassim Al-Shaker was 19 years old when a group of militia men kidnapped and tortured him at his barbershop in Iraq for drawing the Venus de Milo. The violence roused him to the dangers of being an artist in his native country, but he refused to give in to such threats, eventually becoming a professor of fine arts in Baghdad.

News that puts power under the spotlight and communities at the center.

Sign up for our free newsletter and get updates twice a week.

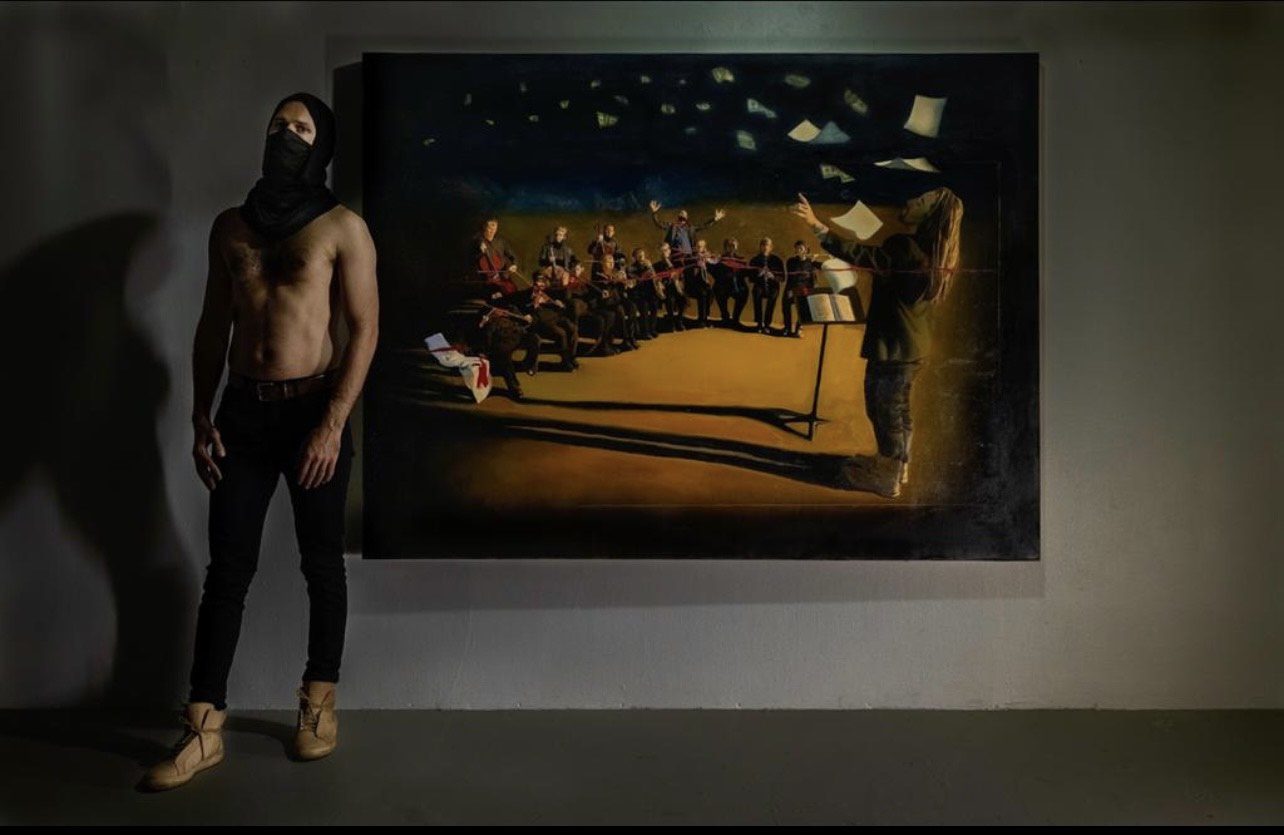

Now 35 and living in Chicago, the Iraqi artist is internationally recognized for his oil paintings that draw on his experiences growing up before and after the 2003 U.S. invasion of Iraq. These works are powerful allegories of the war that distill the complexities of revolution, immigration and freedom through realist, often unflinching imagery. His pieces have been exhibited around the world, from the 2013 Venice Biennale to several galleries in Chicago, where Al-Shaker earned his Masters of Fine Arts in 2021 from the School of the Art Institute of Chicago.

Since moving to the U.S. in 2013, Al-Shaker has continued to raise his international profile. This March, he will be in a group show at Zolla / Lieberman gallery and in June he will participate in the world’s biggest contemporary art show, Documenta, in Kassel, Germany, where he will debut a documentary based on his life that he produced, animated and is featured in.

Borderless Magazine spoke to Al-Shaker about his immigration experience and how he defines himself through his love for art and creativity.

[Editor’s Note: This story contains paintings depicting violent imagery.]

I have been painting since elementary school. My uncles are musicians and my father is a painter. Seeing my family around famous musicians in the Arab world sparked my dream to become an artist. But I took my own path. Art is sometimes seen as a technical thing: You paint something and sell it. But I look deeper into painting as a form of therapy. I needed to speak about myself and speak to others through painting.

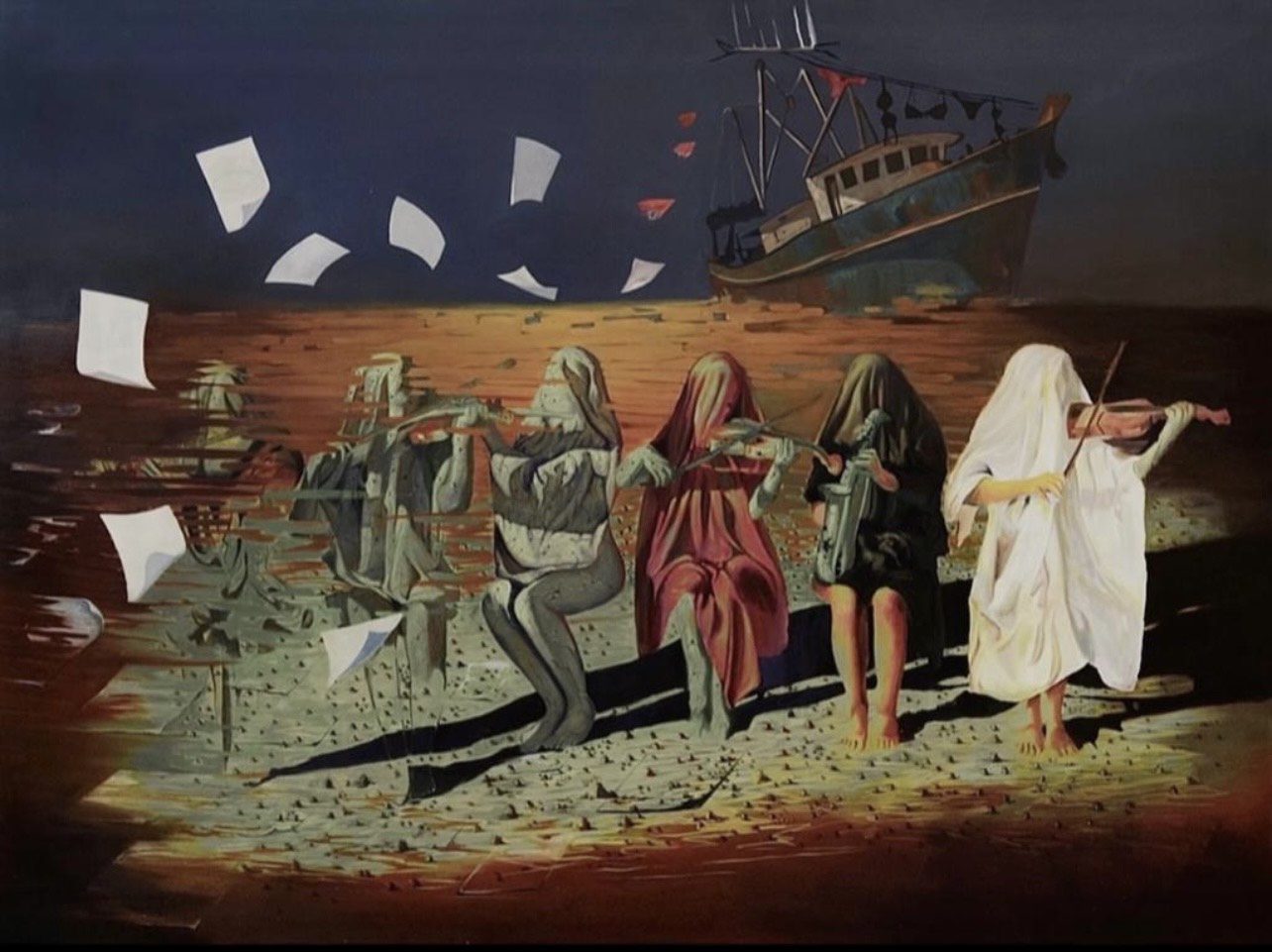

Many of my paintings are driven by the situation in Iraq, the place I grew up with all my friends and family. In October 2019 there were massive protests across the country against corruption, high unemployment and foreign interference, and to fight for basic public services and rights. Hundreds were killed and thousands were injured by the government and militias. My oil painting “Parliament Nightclub” and the series “Halal” were inspired by the protest and caused a lot of hate messages through social media because they highlight sectarianism. But if my paintings don’t cause problems, it is not a painting.

The painting “Halal” shows people sitting around a dinner table: One religious Shia clergy, one Sunni clergy, then Qassem Soleimani [before he died] and a politician for the Iraqi government who works for foreign countries. This painting is not only about the protests but also the militias in Iraq. More than 22,000 people were injured, and the government and sectarian groups allowed the casualties and deaths. The body you see in the middle of the table, although shaped in a woman’s form, is not a man nor a woman — there are no breasts on it, and actually there is hair on the head. This body represents their dinner. The militia kills both men and women without discrimination. The person laying on the table is wearing a mask with smoke coming out of their head, representing the tear gas that has caused thousands to die.

The October protests inspire me to paint, but so do the layers in me, made of my life experiences I faced until today. The revolution is already in me.

Read More of Our Coverage

Life in Iraq was amazing. By the age of 15 I was a barber, owned my salon, and I was getting my Bachelor of Art at Baghdad University’s College of Fine Arts. But once the 2003 war happened, the lifestyle quality went down too quickly, and I could not handle living there anymore.

One night at my salon in 2007, around 10 p.m. a group of Mahdi militia men wanted to cut their hair. As they walked into my salon they noticed my drawing board with Venus de Milo, which I was practicing for a college exam. When they saw the nude drawing, they all of a sudden wanted to fight. They beat me, abused me, put me in the chair and started cutting my hair, and they eventually dragged me down the street. Eventually the group of guys were arrested by the American army.

After the incident at my barber shop, they threatened to kill me if they found me painting. I reached a point where I was unable to paint in my own home. Those groups of men are not just bad people but jealous people. They are uneducated about real life and don’t know anything except how to murder and hurt others.

I always tell my friends in Iraq, if people do not paint or do art, I feel very bad for them. I put all my feelings of negativity, stress and energy into art. There is something I can take from inside me and put outside, which clears my inside. A lot of friends here in the U.S. ask me if I go to therapy after all I went through. Art is my therapy, which is why I was painting so much in Iraq during and after the 2003 war. Before 2003, art was seen as something nice and likeable. But after, this conservative, extremist mentality came out, and art was seen as haram. But I do what I want, fuck everything. Period.

In 2013, I was getting ready to go to Italy because I was chosen to represent Iraq at the 55th Venice Biennale. My brother informed me that the group of men who beat me up were out of jail and furious. That same night at 12 a.m., one of my friends knocked on my door very hard, telling me, “Those militia men who beat you and hurt you think you are the one who called the American army to arrest them, and they are now planning to kill you.” I left home that night and just waited in hiding for a month until my flight for Italy.

That year, I had also gone to Lebanon for art workshops sponsored by Sada for Iraqi Art, a nonprofit art education project to support young Iraqi artists. Rijin Sahakian, the founding director at the time, knew about me and was concerned about my safety. In Venice, she connected me with Gordon Knox, who was the director of Arizona State University’s art museum, which had a residency program for foreign artists. He eventually offered me a residency with a budget, studio and translator.

After the Venice Biennale I went back to Iraq for 10 days secretly, without anyone knowing, to renew my visa to travel to the U.S. That was the beginning of my new life. I was 24.

When I first came here I knew no English. That delayed me a bit, and it was extremely hard for the first six months. I would learn a specific English sentence and talk to random people on the street on my morning bike ride. I would repeat only sentences I knew and didn’t even know what they would say back. I would go to a restaurant, bar or whatever public setting and speak more comfortably and not be shy.

After arriving in Arizona, I had three months until my visa expired. Then I was featured in a New York Times article in August of 2013 that got a lot of attention. It was translated into several languages and shared around. Lawyers who heard it contacted the museum telling them they wanted to help me stay in the U.S. The museum chose a law company that eventually did all my paperwork for me for free. So I got extended to stay here through an artist visa, which is one of the hardest visas to obtain, then I got a green card. Today I am a citizen.

But even though I live in the U.S. I am not fully free because I cannot go back to Iraq because of my paintings. I am happy in life and extremely proud of myself. If someone looks at my life today they would not suspect I went through this.

Seeing my art spread everywhere makes me happy.