Carlos Barberena

Carlos BarberenaAhead of his new exhibition in Milwaukee, the Chicago-based artist talks about his work and the radical democracy of printmaking.

Carlos Barberena became an artist to show the world who his people are.

Want to receive stories like this in your inbox every week?

Sign up for our free newsletter.

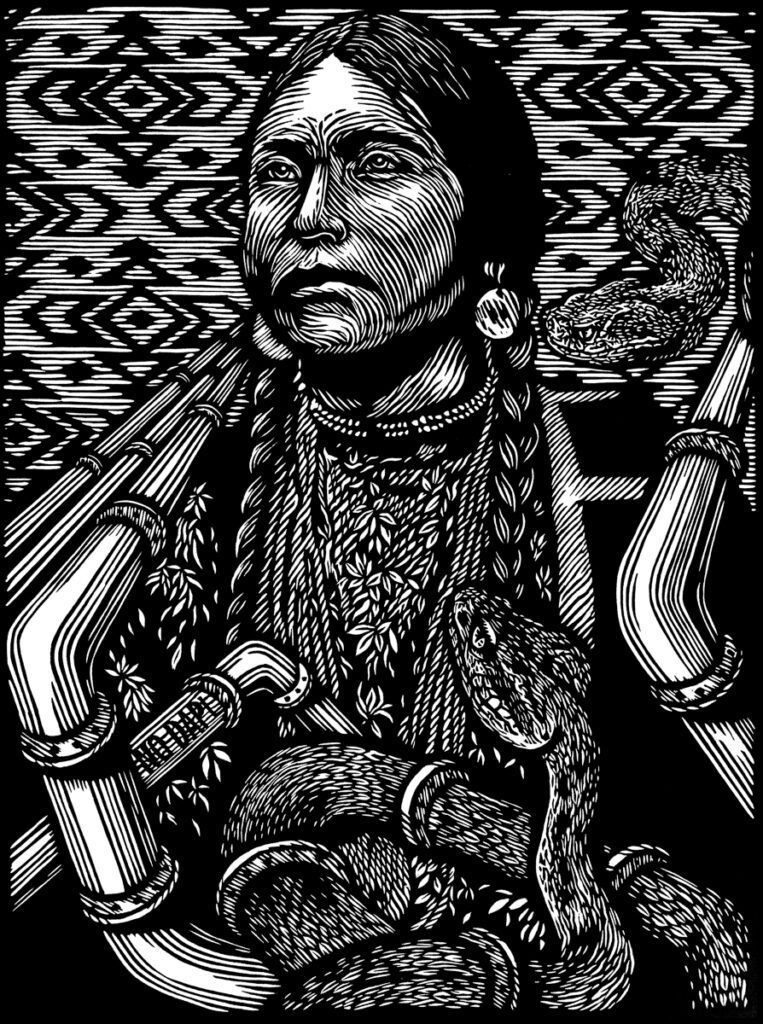

The Nicaragua-born, Chicago-based artist creates intricately carved, monochromatic linocut prints that often depict the issues and experiences of migrants from Latin and Central America, such as their perilous journeys to the U.S. His dramatic works often feature drawings of Black and Brown people who are part of movements for justice, from George Floyd to an Indigenous woman protesting the Dakota Access Pipeline, depicted with the pipeline snaking around her torso. Though sometimes somber in tone, Barberena’s prints also use satire to invite societal critiques. At other times, he hopes to show the humanity of migrants and how everyone deserves a safe and healthy life.

Printmaking has long been used to advance radical causes and spread awareness of social issues. Barbarena, who moved to the U.S. in 2008, follows in this tradition. He cites as an influence the German Expressionist printmaker Käthe Kollwitz, who was concerned with the plight of the working class. And his works align with those of contemporary artists such as Nicole Marroquin and Favianna Rodriguez, who have also used printmaking to champion migrant rights.

In his new exhibition at Milwaukee’s Latino Arts Inc., “I Have Been a Stranger in My Own Land,” Barberena shows a recent series of prints that highlight the importance of essential workers. Also on display are works that consider the difficult choices people have to make when deciding to leave their home countries.

Read More of Our Coverage

Borderless Magazine spoke with the artist about his new exhibition and his journey to printmaking.

I was born in Granada, Nicaragua. There are a lot of artists there: poets, painters, singers. I grew up in this environment, going to my grandma’s house with musicians and poets that were visiting and having cultural conversations. I have two brothers who are artists as well, so growing up in that environment, it was very natural for me to start drawing. When my mom realized I was another artist, she sent me to a popular cultural school.

The late ’70s and early ’80s were a time of revolution. Art in school was very conservative. I remember I was drawing a bottle. My brothers were at the national fine art school in Managua and were experimenting with Cubism, so I drew the bottle in that style, and the instructor tore up my drawing. He said: “You have no talent. I don’t know what you’re doing here.” I was 10 years old. I was like, I don’t want to touch a pencil anymore in my life. I felt a lot of frustration.

After the civil war and with the U.S. embargo in Nicaragua, my mom said, “You have to leave.” I was 13 years old and went to Costa Rica for high school. I started to realize all the things that immigrants feel — xenophobia, discrimination, that you are a criminal, you are taking our jobs. I started to try to put all those feelings together in some way. I found art again.

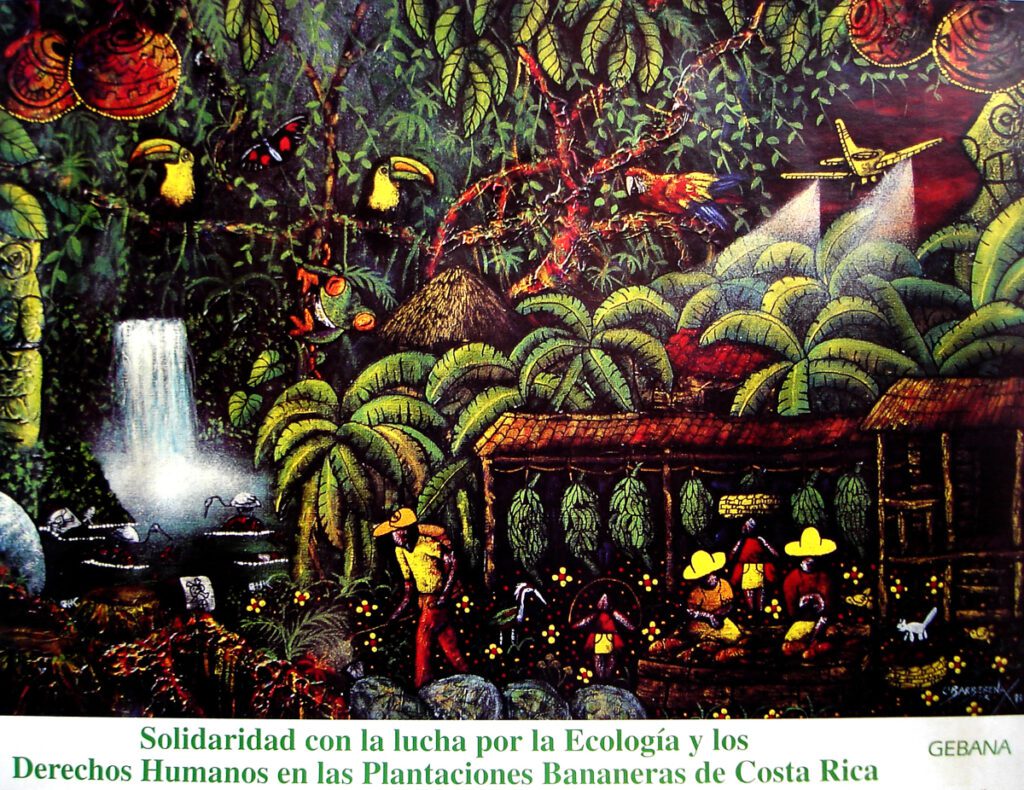

My brother saw my drawings and was like, “We could sell these.” We went to a gallery in a hotel, where a woman sold souvenirs, and she liked my drawings. I started producing more and more. It was always partly because I wanted to show people who Nicaraguans are. Because I moved from Nicaragua, I was having to find my own roots and history. I did a poster about the pesticides that are prohibited in the United States, but the U.S. sells them to Central America. A labor rights organization named ASEPROLA invited me to submit a poster design for workers’ rights in the banana plantations in Costa Rica and the impact of pesticides on the environment. My proposal won, and the German fair trade organization GEBANA printed 5,000 posters to raise funds for workers rights in Costa Rica.

After drawing, I painted for several years, and my work started changing again. It was more political, more about the history of my country. I had been out of my country for seven years and I decided to go back and work there.

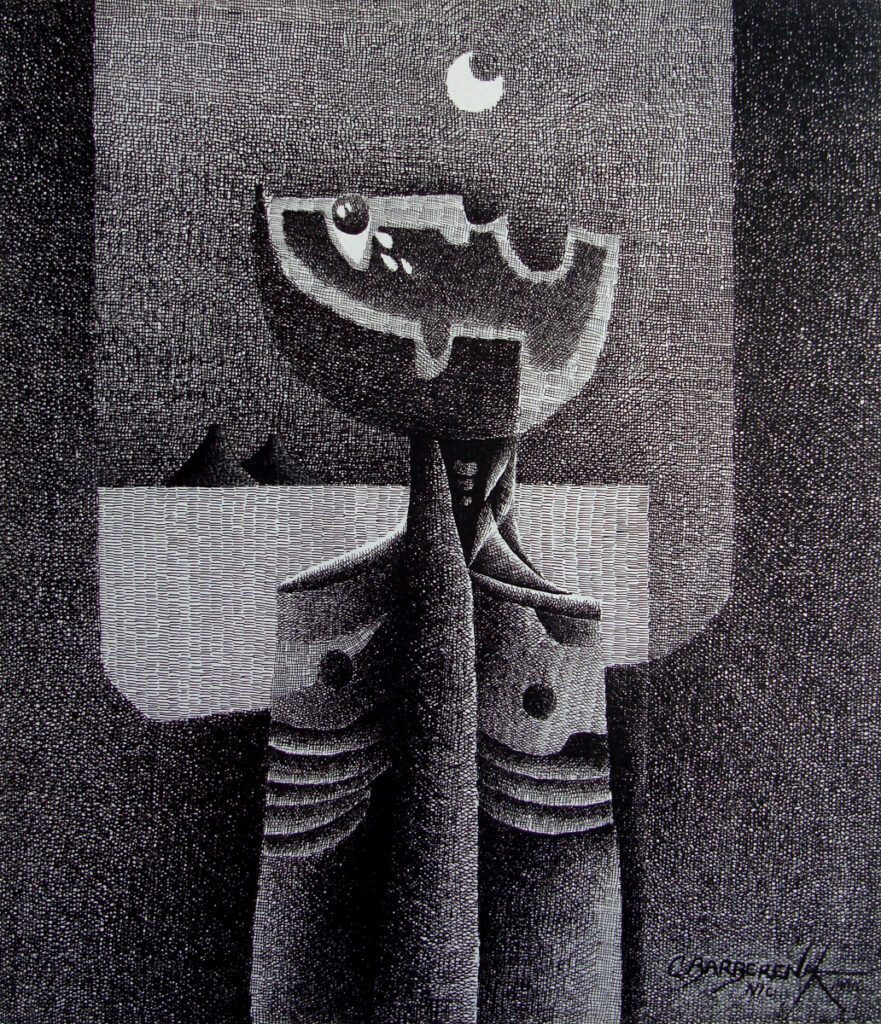

In 1999, I created a series called “Años de Miedo / Years of Fear.” It was a reflection about the effects that war has on human beings, on the psyche. My country went from a dictatorship — from the Somoza family that ruled the country for 45 years — to a revolution. After the civil wars, we had the embargo, we had the Contras sponsored by the United States. All these people dying for nothing. It was challenging because nobody wanted to talk about it. My contemporaries were doing more commercial work.

I was invited to do a residency in Mexico in 2007. It was my first time in the big city, with big museums. At the National Museum of Art (MUNAL), I went to a show of José Guadalupe Posada. That changed everything for me. He had work that was satire. I said, I could do this, because I always had this problem with people thinking that my work is very serious and depressing. That was the day I decided to be a printmaker. I wanted to be like Posada. I went back to Nicaragua and, with one of my brothers, started touring in Nicaragua, showing the techniques, which I had learned at a cultural center in my hometown, Casa de Los Tres Mundos. That was the other thing I learned there, how printmaking is always a community of artists sharing. Everybody is working together.

I have always been interested in the educational part. After moving to the United States in 2008 and joining Instituto Gráfico de Chicago, we started Grabadolandia in 2013. It is a three-day printmaking festival open to the community, giving opportunities to people to learn about printmaking. Everything is free. The artists don’t have to pay any fee. They can sell their work there — we ask them to have affordable work so everybody can take art home — and they do a demonstration. It’s always amazing to see kids playing with the stamps and learning about it.

The way that I work is I start with an idea and a reference image, like a photograph, and I draw on a piece of linoleum or wood, making my own design. Then I carve away around those lines. With printmaking, because you have multiples, you can reach more people. People always say it’s a more democratic technique and it is, because that piece could be in a museum, in a gallery, in the streets, on a T-shirt at the same time. That is the wonderful part of printmaking.

The show in Milwaukee is mostly focused on immigration and what issues push people to leave their own countries, like dictatorships or violence in their country. It is a reflection of the cycles of repression and resistance, and the relationship of resistance with the diaspora. People have always been coming here and looking for the American Dream.

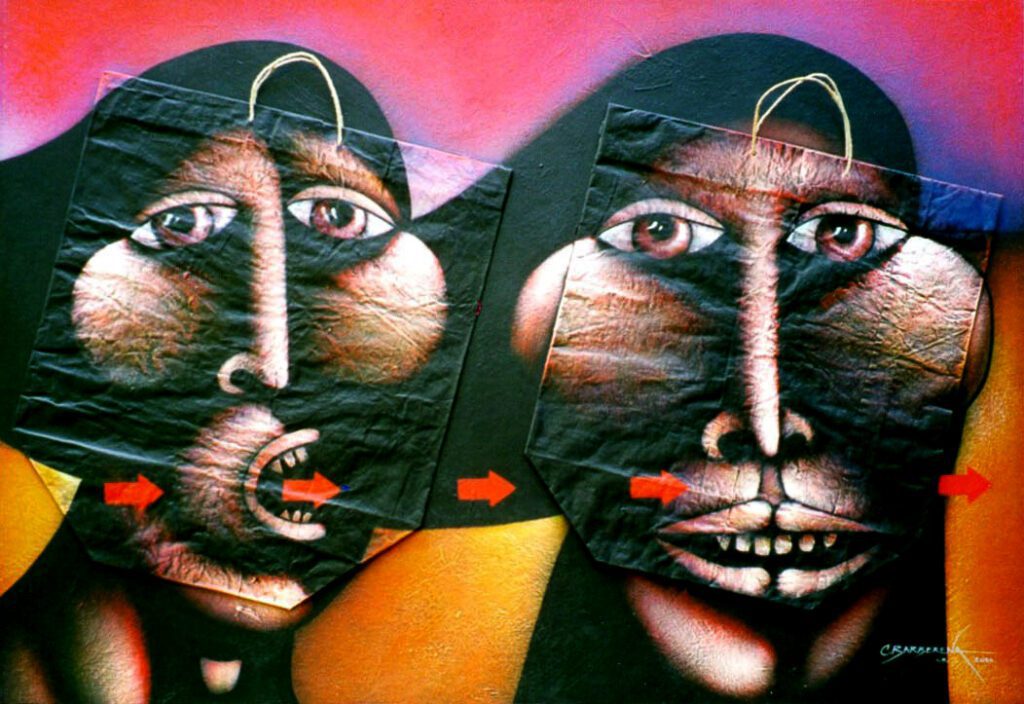

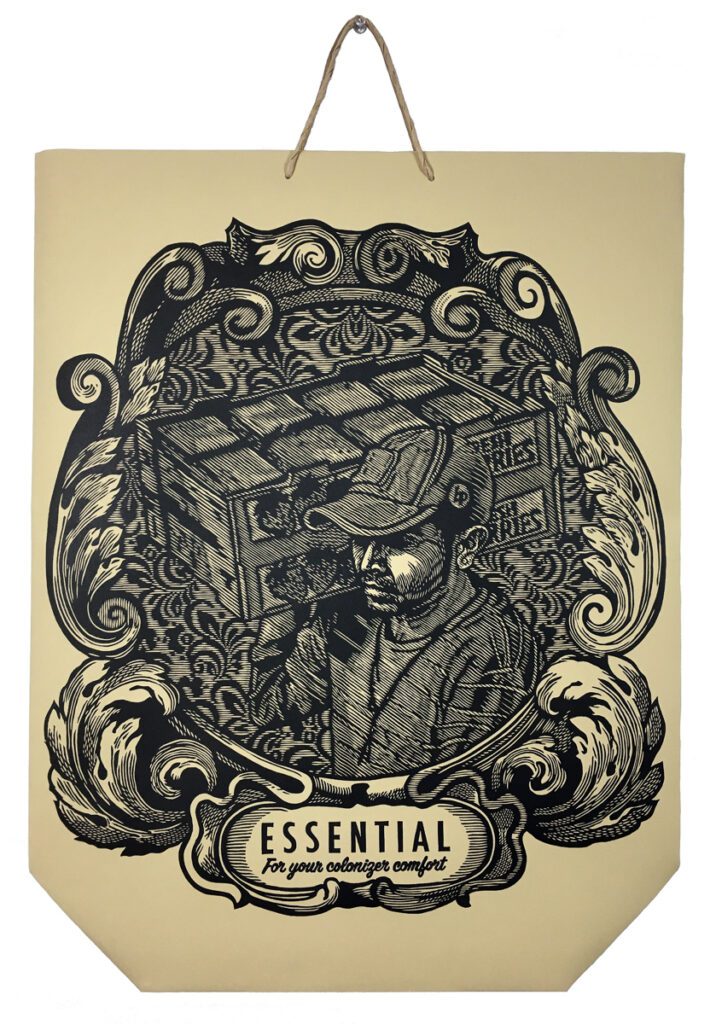

My series “Essential: For your colonizer comfort,” which is on display, honors farm workers, most of whom are undocumented, and creates awareness about why they are “essential workers.” The U.S. population and federal government labeled them “essential” in the context of COVID, a so-called honor for their centrality to the food system, while doing little to alleviate their lack of basic rights and vulnerability to exploitation and imminent deportation.

People are working more than 12 hours straight and didn’t receive any check from the government because they are undocumented. We go to the supermarket, buy the food, but we are not thinking of the people working there. Maybe we can’t see farm workers here in Chicago directly. But we are part of this food chain.

In the last four years, I have been hearing this speech of hate against immigrants everywhere — that we are just here and we don’t do anything. My art is a way to say, “We are here and we are going to stay, like it or not. We are giving to this country, but we are not receiving the same fruits as the rest.” My work can add a little to the cause.

“Carlos Barberena: I Have Been a Stranger in My Own Land” is on view at Latino Arts Inc. through March 11, 2022.

Bring power to immigrant voices!

Our work is made possible thanks to donations from people like you. Support high-quality reporting by making a tax-deductible donation today.