Martine Séverin for Borderless Magazine

Martine Séverin for Borderless MagazineShe was born in a refugee camp. Now, she helps other girls who have been displaced build their own community.

Pew Research estimates 1 in 10 Black people in the United States is an immigrant. In Black Immigrants Today, Borderless Magazine spoke to Black immigrants around Chicago about their homes, their lives, and the challenges they faced coming to the U.S.

Lillian Ingabire is a storyteller: she creates visual narratives through print, web, and social media design. She enjoys celebrating the stories of others like her through her work with GirlForward, an organization that supports girls who are refugees or asylum seekers. As a storyteller, Lillian’s art and writing is a way for her to navigate her multifaceted identity as a Black person, a woman, a refugee, and the eldest daughter of an immigrant family.

Lillian’s parents and late older brother were a few of the hundreds of Hutus who fled into the Congo rainforest, in what was then Zaire, to escape war after the Rwandan genocide. In just 100 days in 1994, nearly 800,000 Tutsis and moderate Hutus were slaughtered by Hutu extremists. The region remains unstable.

Want to receive stories like this in your inbox every week?

Sign up for our free newsletter.

Lillian doesn’t have any memory of the Mbuji Mayi refugee camp that her parents wound up settling in, but she knows that it is only part of her story. After living in refugee camps, Lillian and her family started a new life in Chicago in 2011 where she now gives back to the refugee community.

Lillian spoke with Borderless about her parents’ efforts to start a new life in the U.S., how she shaped her identity around her journey and what Blackness means to her.

My parents are originally from Rwanda and had to run away from the genocide that was happening. They fled into the Congo rainforest and found shelter in a nearby village. They then made their way to a refugee camp in the Democratic Republic of the Congo where they had my older brother. But the war eventually spilled into the Eastern Congo and my parents had to escape yet again. As they hid in the rainforest, my brother grew sick and died.

Several months later, they made it to the Mbuji Mayi refugee camp, where I was born in 1999. My grandmother on my father’s side was also with us. I have no memory of the camp, but my parents have always been open about this part of our lives. They gave me the last name Ingabire, which means “the gift” because when they lost my brother they had asked God for another child.

We moved around a lot until we found ourselves in Lusaka, the capital of Zambia, and I was there throughout most of my childhood. I have really fond memories of that time, especially going to school. I really excelled in school and was at the top of my class. But in the background, my parents were going through the long and complicated process of resettlement.

Read More of Our Coverage

The Hutus were blamed for the genocide and ongoing war that had spilled into the Congo so my parents wanted to remove us from the distrust people felt about them in Africa. My parents were going through multiple interviews and applications, while I was blissfully unaware, playing with my friends and taking care of my younger siblings.

During the resettlement process, we had to leave our home to move into Meheba refugee camp in Zambia. My parents would spend hours upon hours in what looked like CIA-style interrogations with immigration officers. In addition to more interviews, we were also required to complete extensive medical evaluations. In 2011, the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) assigned us to relocate to Chicago. I remember it was such a long plane ride; I felt like we were on the plane for days. I was eleven years old when we came to the United States.

It was a crazy experience. Catholic Charities helped us by locating an apartment for us to rent and furnishing it with donated items. They gave us video games, and I remember fighting over them with my siblings. But the amount of help that was given to us quickly dwindled, and we were left to adjust on our own. My parents worked a lot to keep up with all the bills.

Even though I already knew English, my accent gave away how different I was when I started school and tried interacting with my classmates. I remember that I had to frequently prove my intelligence to people. I had to take in this new culture and had to form a new identity for myself. I have one foot in Africa and another in America. But my heart will always be in Africa.

Read More of Our Coverage

I was shocked that people pay so much attention to race here. The first thing that people notice about you in America is your skin. In America, anyone who looks Black is lumped together into one group. I always say, if the police pull you over, they’re not going to ask, “Are you African or African American?” Your identity doesn’t matter. Your self-worth doesn’t matter. It’s as if race is weaponized here.

Sometimes it’s still hard for me to understand the concept of race in America. When I think about being Black in America, I think about how we focus on the wrong things. In Africa, we focus on who surrounds you, who is your family? Who are your people? I will always identify as being African first and forever.

After we resettled here, I did a lot of after school programs when I was in middle school. The programs were mainly services for refugee students and parents. Later, I connected with GirlForward when I was in high school. It was really amazing being in a space that was just for girls. We all had similar experiences and it was easy to relate to everyone. I was able to explore the city with a mentor, which really made an impact on me. It gave me a new sense of home.

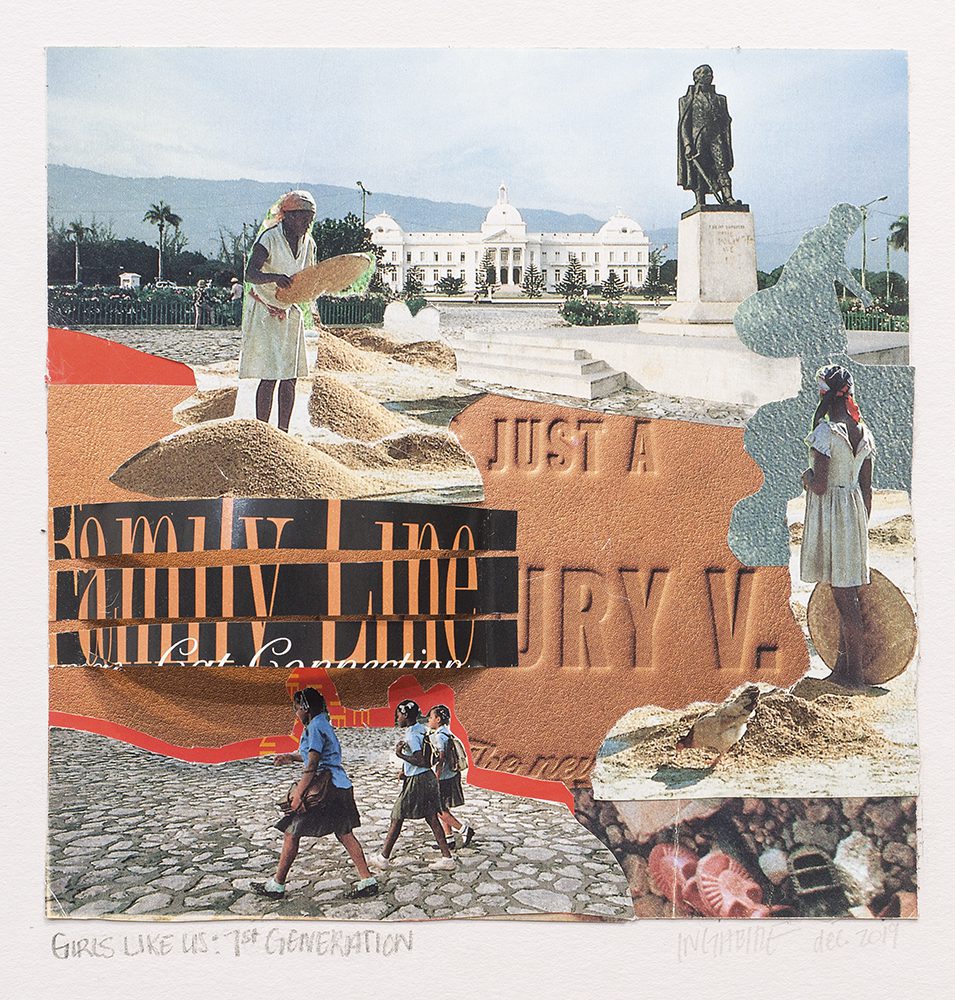

While I was in college in 2018, I studied studio art. I enjoy creating art in all forms as it is another form of storytelling. I find that art, including design, is quite receptive, in that one can use any form or medium of expression. It’s also very forgiving because the work does not need to be perfect in order to be experienced. Currently I gravitate toward making collage art and art installations.

After college, I returned to GirlForward and interned there during their summer program. I wanted to uplift other people like me. Now I’m working with GirlForward full time as the marketing and communications manager. I started in July 2022 and am in charge of digital marketing and storytelling to drive brand awareness, audience engagement and increase funds. I truly enjoy collaborating with the girls at GirlForward to craft and tailor their unique stories to multiple audiences.

I also joined the advisory board of Refugee Action Network in 2021. I offer feedback and ideas to major community non-profits regarding the needs that affect the refugee community. It’s important to celebrate the potential of refugees by giving them the space to use their voice and share their stories.

I’m grateful to have been able to visit Rwanda with my mother, who hadn’t been home in years, in 2018. It was the first time that I met my grandmother and the rest of my extended family on my mother’s side.

The people of Africa are strong and resilient. I don’t like the stereotype of African countries as being perceived as poor and horrible. It’s time that we diminish this idea of Africans having the inability to excel. Don’t underestimate Africans.

This story was produced using Borderless Magazine’s collaborative as-told-to method. To learn how we make stories like these, check out our as-told-to visual explainer.

Bring power to immigrant voices!

Our work is made possible thanks to donations from people like you. Support high-quality reporting by making a tax-deductible donation today.