Courtesy of Counterpoint Press

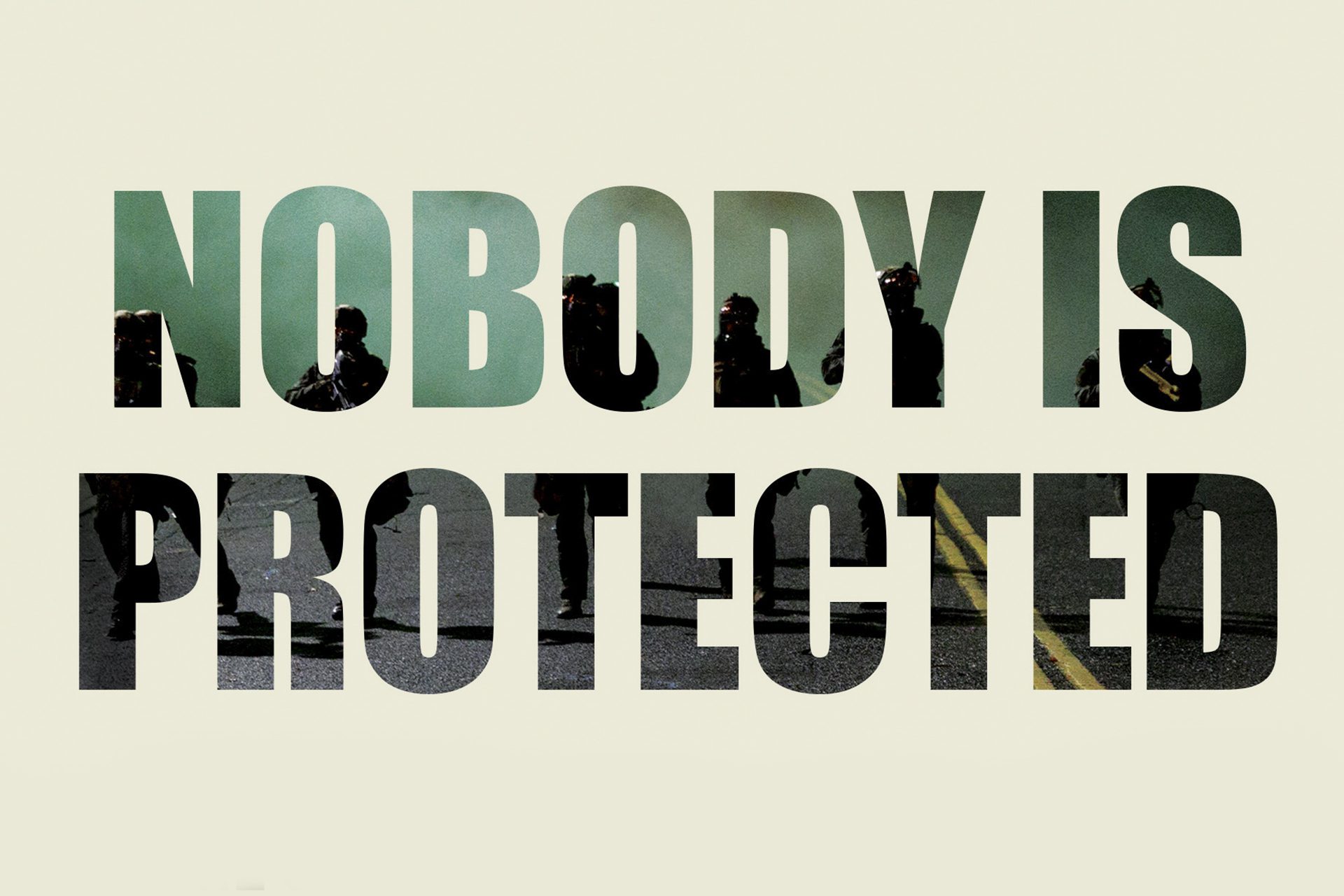

Courtesy of Counterpoint Press In his new book, Reece Jones traces the Border Patrol’s growth into a militarized force that operates in large swaths of the United States.

In July 2020, as people across the United States protested the murder of George Floyd by Minneapolis police officers, a group of armed agents in unmarked vans began detaining protestors in Portland, Oregon.

The agents were only identifiable by generic “police” patches on their vests. But they turned out to be members of an elite U.S. Border Patrol tactical unit, a revelation that had many Americans wondering why the agency was responding to a civil demonstration far from what they considered a national border.

Want to receive stories like this in your inbox every week?

Sign up for our free newsletter.

In his new book, “Nobody is Protected: How the Border Patrol Became the Most Dangerous Police Force in the United States,” author and political geographer Reece Jones pulls back the curtain on the Border Patrol and its expansive role.

Portland, it turns out, is part of the “border zone,” as are Chicago, Detroit, Seattle, San Francisco, New York and other cities within 100 miles of a national border or coastline. And the agents involved in those late-night detentions were operating under a section of law that no longer requires the Border Patrol to have an immigration-related purpose for its work.

What began as a small agency that patrolled the American frontier has since evolved into a heavily-militarized Border Patrol that operates under carved out exceptions to constitutional protections – making it the “most dangerous police force in the United States,” Jones writes.

The following excerpt from “Nobody Is Protected” describes how the Border Patrol has stopped and detained people based on race, especially Spanish-speakers, in the border zone.

Ana Suda and Martha “Mimi” Hernandez were chatting as they waited in line at the Town Pump convenience store in Havre, Montana, in the late evening of May 16, 2018. Both women were certified nursing assistants at the Northern Montana Care Center. They would often go to the gym together in the evening after their children went to bed and would regularly stop afterward at the store to pick up some groceries.

Havre, a small farming town thirty miles from the Canadian border, has a population of fewer than 10,000 people, 81 percent of whom are white. Native Americans make up the second largest group, with 13 percent. The Latino/a population is only 4 percent, or about 400 people. Havre was founded in the 1890s as a stop on the Great Northern Railroad that linked Minneapolis with Seattle. The town has a network of underground businesses that were dug over one hundred years ago as a refuge from the biting winter winds. The underground mall, which is marked at street level by purple tiled skylights, once held a bar, a Chinese laundry, and a bordello, but is now a tourist attraction. Despite its small size, Havre is the hometown of two former governors of Montana, Stan Stevens (1989–1993) and Brian Schweitzer (2005–2013), as well as Montana’s Democratic senator, Jon Tester (2007–present). Jeff Ament, the bass player in the rock band Pearl Jam, is also from Havre.

Ana and Mimi were speaking to each other in Spanish when Border Patrol agent Paul O’Neill walked into the store. O’Neill, with a thick brown mustache and crisp green uniform, was immediately suspicious because he thought no one spoke Spanish in Havre. He got a water from the cooler and then stood in line behind the two women in order to eavesdrop on them.

Havre is a small town where everyone knows each other, and people often greet each other in stores. Mimi turned to O’Neill and said, in English, “Hi, how’s it going?”

Agent O’Neill said, “Hi.” Then he commented on how strong her accent was and asked, “Where are you from?”

Ana and Mimi were surprised. They said, “We’re from Havre.”

Both women were American citizens born in the United States. They had moved to Havre in the previous decade, Ana in 2014 for her husband’s job and Mimi in 2010 because she fell in love with the area after a visit. As longtime Havre residents, they did not recognize O’Neill and were actually wondering where he was from. The women continued their conversation in Spanish.

Agent O’Neill flashed a knowing smile and then said, “Yeah, okay, but where were you guys born?”

The women were annoyed at this point. “Seriously?” they asked.

Agent O’Neill noted their confrontational tone and said, “I’m very serious, actually.”

Ana told him she was born in Texas; Mimi, California. O’Neill was not convinced, particularly because he could not believe that Mimi would speak accented English if she was born in California. He asked for their IDs and both women gave him valid Montana driver’s licenses.

Read More From Author Reece Jones

Agent O’Neill knew that driver’s licenses were not citizenship documents and continued to harbor doubts that Ana and Mimi were in the country legally. He decided to detain them and took them out to the parking lot beside his white and green Border Patrol truck to continue his investigation. He also called for backup, and several other agents quickly arrived, including a supervisory agent. Other shoppers at the Town Pump gawked at the spectacle of the cluster of Border Patrol trucks and the two detained women in the normally quiet town.

Ana and Mimi decided to record the interaction. On camera, they asked O’Neill why he targeted them.

He responded matter-of-factly, “Ma’am, the reason I asked for your ID is because I came in here and saw that you guys are speaking Spanish, which is very unheard-of up here.” The women decided not to remind the agent that Montana itself is a Spanish word.

The women turned to the supervisor and asked if they would have been detained if they were speaking French.

The supervisor shook his head. “No, we don’t do that.”

After being held for forty minutes, they were released. At no point during the detention did Ana mention that the reason she moved to Havre was because her husband was one of their colleagues who worked for Customs and Border Protection as a field operations agent at the port of entry on the Canadian border.

In 2019, the ACLU filed a lawsuit on behalf of the women, asking for damages for the violation of their Fourth and Fifth Amendment rights. The residents of Havre, however, blamed the women. They were yelled at and harassed in public and Ana was even pushed by a man who confronted her. Their children were called racial slurs in school. Both women were forced to move away to avoid the harassment. Ana went back to El Paso, even while her husband continued to work as a CBP agent in Havre, and Mimi moved to Great Falls, Montana.

As the case made its way through the courts, the ACLU obtained a series of damaging documents about Agent O’Neill specifically and the conduct of the Border Patrol in Havre generally. As part of the investigation of the incident, the supervisory Border Patrol agent who arrived as backup for Agent O’Neill at the Town Pump store participated in an interview with Border Patrol internal affairs officials. The supervisor thought that Agent O’Neill’s actions were routine and well within the norm for agents in Havre. The supervisor even recounted a story about himself when he was at the local mall in Havre with his family on his day off. He was eating at a restaurant when he looked up and saw “two Mexicans” at a nearby store. He debated about whether he should report it to his on-duty colleagues and after a few moments of observation decided to make the call. As he reached for his phone, he realized he was too late. He noticed another off-duty Border Patrol agent with his cell phone to his ear, following the two people about twenty feet behind them. He chuckled, “Really, it’s like that if there is somebody speaking Spanish down here, it’s like all of the sudden you’ve got five agents swarming in.”

The supervisor went on to explain, “It is a small place and we have a lot of agents here. And nobody really has much to do.” The supervisor said he was surprised when he found out that Ana was from El Paso. He felt like she should understand that racial profiling is the norm for non-white people in the border zone. He shrugged and laughed as he said, “What are you complaining about? You’re from El Paso, you do this every day.”

Racial Profiling in the Border Zone

The Border Patrol denies that they use racial profiling as a normal practice in the border zone. They collect data only on arrests, not on all stops or interactions, so they do not have data to prove their claim. However, their training documents give agents an overview of the 1970s Border Patrol cases and expressly allow for racial profiling. The 1981 version of the training materials summarized the articulable facts of reasonable suspicion from the Brignoni-Ponce case but expanded the wording beyond the “Mexican appearance” in the ruling. It lists “characteristic appearance of persons who are from foreign countries” as an example of an articulable fact. The 1999 Laws of Search Manual says agents can use “appearance of the occupants, including whether their mode of dress and/or haircut appear foreign.” By 2012, the explicit references to race were removed from the training manuals, but they still said that appearance could be a fact of reasonable suspicion, including if someone looked “dirty.”

Read More of Our Coverage

Complaints by individuals targeted by the Border Patrol and studies by outside groups have shown that racial profiling is a common practice both in roving patrols like the one that targeted Ana and Mimi and at the interior checkpoints. In an analysis of Border Patrol arrests in Ohio in 2010 and 2011, 85 percent were of Latino/a descent even though they make up only 3 percent of the state population. Although ostensibly the patrols in the northern border region should be targeting entries from Canada, the country across the border, less than one quarter of 1 percent of those stopped by agents were Canadian.

Geoffrey Alan Boyce and the ACLU of Michigan found a similar pattern when they analyzed the Border Patrol’s apprehension and arrest records in Michigan. Although the Border Patrol’s authorization is to stop clandestine entries into the United States, only 1.3 percent of people apprehended in Michigan had crossed from Canada. The majority were longtime residents stopped by the local or state police for a traffic infraction. The Border Patrol was then called when the officer suspected the individual was in the country without authorization. The average person had resided in Michigan 7.36 years at the time of their apprehension.

The Michigan analysis also demonstrated how easy it was for agents to manufacture reasonable suspicion under the guidelines the Supreme Court established in Brignoni-Ponce. No matter what an individual did when they encountered a Border Patrol agent, it was perceived as suspicious. If they drove too fast or drove too slow, that could result in suspicion. If they stared at the agent, that was suspicious in some cases, but in others it was suspicious if they averted their gaze. The records also confirmed that the agents were relying on racial characteristics in their decisions to make stops. In essence, the Brignoni-Ponce guidelines for reasonable suspicion were so broad that the agents could stop any vehicle they wanted.

In Arivaca, Arizona, local residents were frustrated with the Border Patrol’s constant interference with their daily lives. Although the Martinez-Fuerte decision stated that “Motorists whom the officers recognize as local inhabitants, however, are waved through the checkpoint without inquiry,” the residents of Arivaca have found this is not the case. The Border Patrol tries to prevent agents from establishing roots in the local community because they believe it makes them susceptible to corruption and smuggling. Instead, agents are typically rotated through different postings every few months, before they can become familiar with the local population. The residents of Arivaca formed an organization called People Helping People, initially to provide humanitarian aid, but later they began to monitor the Border Patrol’s activities in town and on the highways nearby.

Arivaca is a tiny town with a population of only 700, about eleven miles north of the U.S.–Mexico border. It has a post office, a restaurant, and a small grocery store along with a few blocks of irregularly spaced homes. There is only one road that passes through town, the two-lane Arivaca Sasabe Road. To the east, it is a thirty-minute drive to Interstate 19, which connects Tucson and Nogales. To the west, the road winds through the Buenos Aires National Wildlife Refuge for twelve miles before it hits Route 286, the north-south road that connects the border town of Sasabe with the western suburbs of Tucson. No matter which way they go, residents of Arivaca have to pass through at least one Border Patrol checkpoint to drive to any other part of Arizona.

Rather than refusing to comply with the Border Patrol’s requests like Terry Bressi, the University of Arizona astronomer, People Helping People instead started to simply show up at the checkpoints and observe what was happening there. They would bring folding chairs, cameras, and notebooks to monitor the activities of the agents. From their perspective, it was a public road so they were free to sit on the shoulder for as long as they wanted.

The Border Patrol did not see it that way. On the first day of observation, the Border Patrol threatened to arrest the monitors and called the local police. The Border Patrol tried to prevent them from observing at all and then expanded the size of the checkpoint so the monitors were forced to sit far from where the stops occurred. The agents parked vehicles in front of them to block their view and left the engines running for hours with the exhaust pointed at the observers so they had to breathe in the noxious fumes. The Arivaca residents filed a lawsuit against the Border Patrol on First Amendment grounds, which is ongoing. In 2014, People Helping People released a report on their observations of the Amado checkpoint, to the east of Arivaca toward I-19. Between February 26 and April 28, 2014, People Helping People volunteers counted 2,379 vehicles that were forced to stop by the Border Patrol at the checkpoint. They found that cars with only Latino/a occupants were twenty-six times more likely to be asked to show ID and twenty times more likely to be referred to secondary inspection compared to vehicles with white occupants. The report also raised serious questions about the efficacy of the Amado checkpoint. During the entire one hundred hours of observation, the Border Patrol did not make a single immigration apprehension or drug seizure.

Excerpted from Nobody Is Protected: How the Border Patrol Became the Most Dangerous Police Force in the United States, copyright © 2022 by Reece Jones. Reprinted by permission of Counterpoint Press.

Bring power to immigrant voices!

Our work is made possible thanks to donations from people like you. Support high-quality reporting by making a tax-deductible donation today.