Youngrae Kim for Borderless Magazine

Youngrae Kim for Borderless MagazineWith increased violence against Asians, community groups are taking action, from distributing self-defense tools to gathering critical data.

Summer of 2021 was busy for 34-year-old Kevin Chang. While working as a full-time doctor, he wanted to find other ways to protect Chicago’s Asian American community in a time of increased anti-Asian violence. In early April, Jin Yut Lew, a 61-year-old Chinese man and former chef, was found carjacked, beaten and unconscious near Chinatown. Attacks like this prompted Chang and his four peers to start a GoFundMe page in May. The goal was to raise money for personal keychain alarms to distribute to older adults, a demographic that reported 126 accounts of harassment or assault nationally between March 2020 and December 2021, according to the coalition Stop AAPI Hate.

The fundraiser was one of myriad efforts across the U.S., from California to New York, to empower Asian communities amid a surge of anti-Asian violence. Community-based efforts in Chicago include data collection, campaigns to raise awareness and the distribution of resources for self-defense like personal alarms or pepper sprays.

Want to receive stories like this in your inbox every week?

Sign up for our free newsletter.

In May alone, at least three incidents have prompted authorities to investigate them as hate crimes. At Tops supermarket in Buffalo, a white male mass shooter killed 10 Black people. In Dallas, three Korean women were injured during a shooting at a hair salon in Dallas’ Koreatown. And in Laguna Woods in Southern California, a Chinese immigrant targeted a Taiwanese church, killing a parishioner and wounding five elders.

While organizers aim to support community members, they also want to inform the broader public that attacks still happen regardless of attention from mainstream media. For many, the violence is nothing new. It reflects a long history of structural racism made clearer with increased xenophobia during the COVID-19 pandemic. While many government officials have responded to heightened violence with greater policing, many Asian community leaders have rejected this strategy, citing police misconduct and abuse of power. A survey conducted last year by research group AAPI Data also found that Asian Americans are among the least likely to feel comfortable reporting hate crimes to authorities. Language barriers and a lack of legal status can also contribute to this discomfort.

Responding to this distrust in systemic solutions, activists and scholars from AAPI groups have been taking matters into their own hands.

“I do feel like it’s just up to us,” Chang, who is Chinese, said. “There was like maybe 30 or 60 days last year where we got a lot of attention from big stars, but unless you’re Asian and follow certain people from the news, you don’t really hear about this anymore these days.”

After reaping almost $4,000 to purchase 1,800 personal alarms, Chang worked with groups like the Asian American Law Enforcement Association to distribute them. Volunteers also gave out instructional fliers in languages like Mandarin, Mongolian and Vietnamese. Recipient organizations included the South East Asian Center in Argyle, Chinese Consolidated Benevolent Association of Chicago in Chinatown, the Chicago Mongolian Association and seven other senior living apartments and community centers.

Tsegi Batmunkh, president of CMA, said that she prioritized giving the alarms to their women members working late hours in downtown restaurants and members who are delivery drivers.

“A lot of Mongolians drive Uber or Lyft and do a lot of deliveries for Uber Eats and two people were robbed and beaten while on the job,” Batmunkh said, adding that one had to be rushed to the ER. “They were able to get away and just gave their phones, earbuds and other stuff.”

These incidents happened in Chicago, but the 20,000-member network also covers Illinois suburbs and neighboring states like Wisconsin, Michigan and Indiana. As president, Batmunkh feels a responsibility to remind her community members, through internal meetings and social media posts, that safety is number one. “If they’re approaching you for robbery, whatever they want, give it away. Your life is more important,” she said.

These crimes went unreported, Batmunkh said, although she was not able to explain why. But for Jordan Stalker, a research advisor with the South Asian American Policy & Research Institute, part of the reason clearly stems from language barriers.

Read More of Our Coverage

“We looked at the hate crime reporting forms that are available from the Attorney General’s Office and they’re only in Mandarin and in English,” he said, adding that fact sheets are available in different languages, but access to them is inconsistent. “If your level of comfort with the English language isn’t up to a level where you can ask for a reporting form or fill it out properly, then you’re not going to do it.”

In March 2021, SAAPRI launched a survey to collect hate crime experiences from folks of South Asian descent over the age of 18. The project’s main objective is to reduce hate-based violence experienced by South Asian Americans in the Chicago area and make sure that their stories are included in broader conversations about anti-Asian hate, which often focus on East Asians.

“We want to advocate for hate crime reporting forms that include South Asian languages like Punjabi and Gujarati,” said Aakash Ray, a research volunteer with SAAPRI.

Stalker added that some people may not even have the terms to identify a hate crime. “If you don’t know you’ve been a victim of a hate crime, you’re not going to report it as such,” he said.

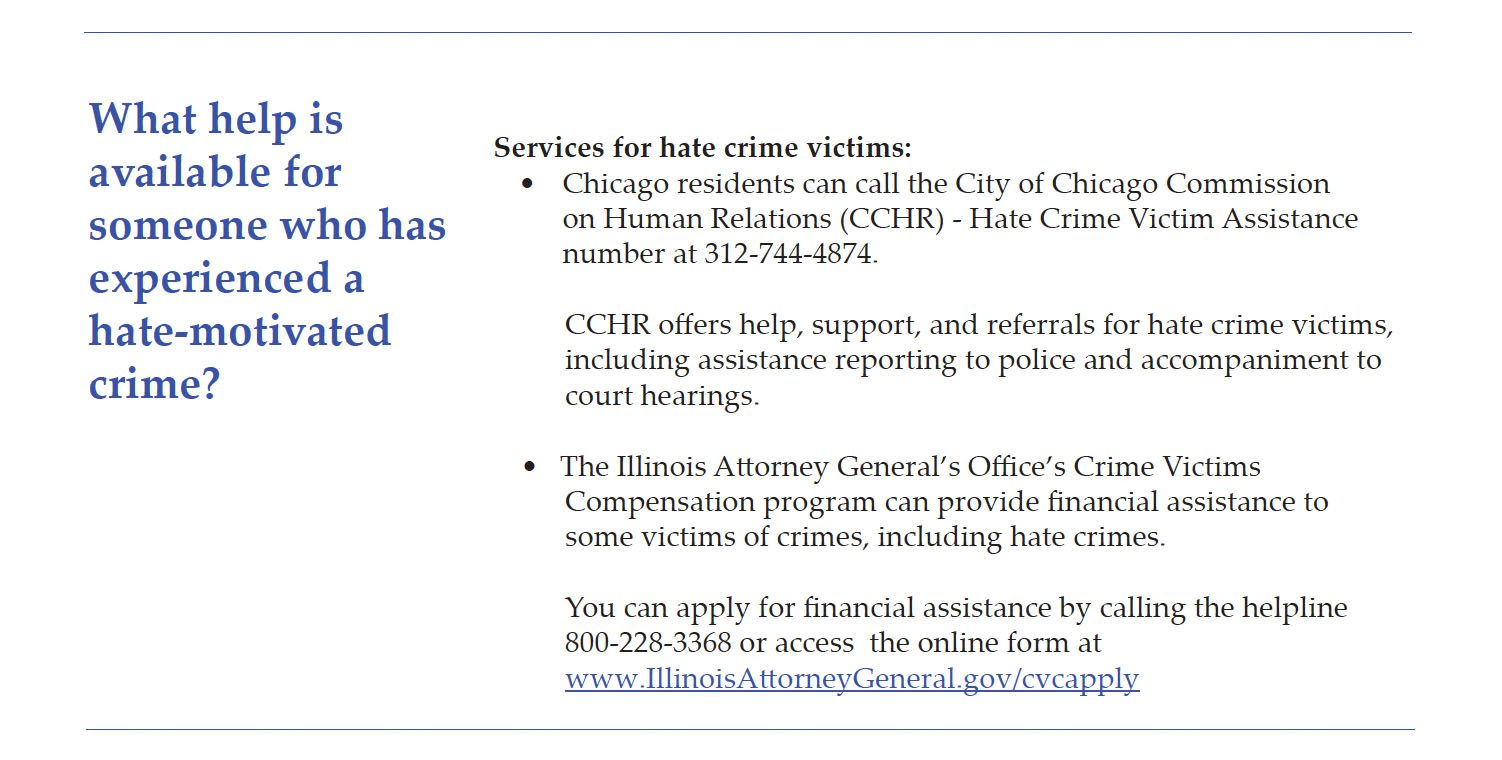

Additionally, it is not always clear how to report hate crimes and what recourse a victim has. The Chicago Police Department has an online reporting system, but because hate crime is not listed as an incident type, a hate-crime victim cannot report their case online. Instead, they must go to one of the department’s 24 police districts or call the non-emergency hotline 311 while simultaneously requesting language assistance if needed and available. CPD did not respond to Borderless’ questions about hate crime reporting.

SAAPRI is still gathering data but has already noticed that many reported hate crimes are verbal, a trend that aligns with Stop AAPI Hate’s own findings. Out of 10,905 incidents self-reported to the national network from March 2020 to December 2021, almost 7,000, or 63%, were cases of verbal harassment.

For Ray, these numbers suggest the immense challenge that the organization faces to combat anti-Asian hate.

“I feel like I understand more of how these systemic problems work. It can be easy to see something like that and say that someone should address that, but it takes so long for these issues [to be resolved],” the 22-year old said. “How do you stop something that’s not tangible?”

Read More of Our Coverage

One nationwide effort aims to directly influence policy makers to better serve AAPI folks. Researchers with the AAPI COVID-19 Needs Assessment Project are identifying and assessing the needs of these communities, specifically during the pandemic. These include mental health and healthcare services that have historically been challenging for Asian American communities, especially immigrants or refugees, to access. Researchers surveyed 3,736 Asian American respondents and 1,262 Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander respondents and found that 75% of Asian American respondents believe that the U.S. had become more dangerous for their racial or ethnic group. Four out of 10 respondents experienced symptoms after a race-based traumatic event, ranging from anxiety to hypervigilance.

For lead researcher Dr. Anne Saw, an associate professor of psychology at DePaul University, the timing of this research is critical.

“We can’t take a break because the minute that we do, people are gonna stop caring,” she said. “People are really hurting and we feel like we are responsible, so this is our moment to actually get people to listen and open up their hearts and their budgets.”

Having finished collecting data for the project, Saw, who is Chinese, has had time to reflect on its impact on herself. She realized that doing this work was her form of community care and self-care during a time when things didn’t feel like they made sense.

“It’s tough to try to put your personal feelings aside, and I haven’t been able to do that,” Saw said. “I don’t think that would’ve been beneficial anyway because part of why we were able to carry it out is because we’re part of those communities … because we cared enough and knew enough to ask the right questions.”

Bring power to immigrant voices!

Our work is made possible thanks to donations from people like you. Support high-quality reporting by making a tax-deductible donation today.