Photo by Camilla Forte/Borderless Magazine

Photo by Camilla Forte/Borderless MagazineBoth President Biden and Illinois Gov. Pritzker have recently changed immigration policies to better protect undocumented families. But for one local father of five, those changes have not gone far enough.

Never miss a story. Sign up for our Thursday newsletter to learn the latest about Chicago’s immigrant communities.

Summer vacation has officially started for the Elizarraraz family.

It’s a sunny afternoon in early June, and siblings Evelyn, 4, Alex, 6 and Jocelyn, 10, splash each other in their backyard kiddie pool in suburban Crystal Lake. Older brothers Aidan, 16, and Isaiah, 19, beat the heat inside the house, while their mother Kristin Glauner and uncle Arturo Elizarraraz relax on a well-worn leather couch in the living room.

From the family photos on the refrigerator to the colorful chalk drawings in the driveway, the family scene is exactly what you might expect on a typical summer day — except one person is missing: dad.

When Elizarraraz’s phone rings, his heart skips a beat. It’s a call from the McHenry County Jail. His brother — Kristin’s fiancé and the father of her five children — is on the line. And he could be deported at any moment.

Cesar Mauricio Elizarraraz, a Mexico-born, longtime Crystal Lake resident, had been in Immigration and Customs Enforcement custody and detained at the McHenry County Jail since December 2019. In late May of this year, the 40-year-old was denied an Emergency Stay of Removal. The court did not give a specific reason for denying the stay of removal, leaving the family to wonder whether it was due to a criminal conviction Elizarraraz received in his youth. His family has since lived with uncertainty, not knowing when, or if, they will be reunited.

“Teenagers make mistakes, I’ve made mistakes, everybody’s made mistakes,” Glauner said. “Me being a citizen, my mistakes aren’t coming back to haunt me. Him? Not. His mistakes have come back to haunt him, but he should not be defined for those mistakes he made over 20 years ago.”

A photograph of Cesar Mauricio Elizarraraz and his fiancé Kristen Glauner hangs on the fridge with art made by their kids in their Crystal Lake, Ill. home. Photo by Camilla Forte/Borderless Magazine

Elizarraraz’s case comes at a time when legislators have made national and statewide changes to immigration enforcement policies in the months since President Donald Trump left office.

Nationally, President Joe Biden promised to reset immigration policy for the U.S. the day he took office. In a February 4 email to ICE officials, then-acting ICE director Tae Johnson advised that people with criminal convictions over a decade old would generally not be prioritized for deportation.

In Chicago, the city passed an updated sanctuary city ordinance in February banning local police and other agencies from working with ICE. At the state level, a bill that would effectively close all detention centers statewide and limit the way local law enforcement interacts with ICE is expected to be signed into law by Governor J.B. Pritzker later this summer.

For Illinois immigrants like Elizarraraz, however, these changes may have come too late. While immigrant advocates have applauded the shifts from the Trump administration, many are still left wondering about the people who may have never been detained or deported were these policies in place mere months ago.

Teenage Mistakes

Cesar Mauricio Elizarraraz came to the United States from Mexico in 1993 as a 13-year-old, with his two younger brothers, Arturo and Ernesto, then respectively 9 and 11. Elizarraraz’s father, who was living in Crystal Lake at the time, had paved a way for his family’s residency in the U.S. by applying for legal permanent status under President Ronald Reagan’s 1986 Immigration Reform and Control Act. The wait time to receive a green card was up to 10 years. Wanting his sons to receive an American education before then, Elizarraraz’s father arranged for a family friend to bring the young boys into the country to Crystal Lake, leaving behind their mother and three younger siblings in the family’s home in Morelia.

Arturo, Elizarraraz’s younger brother, remembers the move being a traumatic experience for all three of them but especially for Cesar. That trauma would stay with him throughout his first few years in the United States.

“Even though we had my dad, and we had aunts and uncles here, it just wasn’t the same,” Arturo said. “Cesar was already sort of rebellious in Mexico in a way … When we got here, he didn’t have my mom, he just got with the wrong crowd right away.”

Cesar Elizarraraz was allowed to return to his family home in Crystal Lake, Ill. on Friday, June 18. He will remain there while he waits for his case to be adjudicated. Photo by Camilla Forte/Borderless Magazine

Frustrated with his environment, Elizarraraz eventually became involved with local gangs in an attempt to find safety from bullying. In February 1996, Elizarraraz’s family home in a predominantly Hispanic Crystal Lake neighborhood known as The Manor was targeted in a gang-affiliated drive-by shooting.

Elizarraraz and his family were at home that night when gunshots hit the house from outside. A bullet grazed his uncle’s head, missing him by just two inches as he sat in the living room.

The McHenry County Sheriff’s Office conducted a police investigation, but charges were never filed. Then in 1998, Elizarraraz got involved in a fight that started with some individuals yelling racial slurs at him and ended with him being charged with aggravated battery.

Working as a painter and living with friends at the time, Elizarraraz yielded a paint scraper during the fight that was later determined in court to be a weapon. After being assigned a public defender, he pled guilty to an aggravated felony. Elizarraraz was just 18 years old.

“They put him on probation and he was doing good, and then I had gotten pregnant and our baby had died halfway through the pregnancy,” Glauner said. “I took it bad. He took it bad — real bad and his probation was revoked due to him smoking weed to cope with it.”

In 1999 — the year the rest of the Elizarraraz family received amnesty under IRCA — Elizarraraz was sentenced to serve out his remaining probation time in prison for violating his probation. After serving his sentence, instead of being released, Elizarraraz says he was brought to a detention center in DuPage County and was told by an ICE officer that an immigration judge would never side with him because of his aggravated battery charge. He voluntarily self-deported to Mexico on March 15, 2000 — the year the rest of his immediate family came to the U.S.

“He had nobody [in Mexico],” Arturo said. “The moment that we were supposed to be a big happy family was the moment that he was gone.”

After spending time separated from his loved ones, Elizarraraz rejoined Glauner and his family in the U.S. in 2001.

“But after he was deported in 2000, that’s when he changed,” Glauner said. “He realized what a couple of years of him screwing up had made him lose.”

Alex Elizarraraz, 6, and Evelyn Elizarraraz, 4, play in the family home’s backyard in Crystal Lake, Ill., under the watchful eye of their grandmother, Mary Glauner, June 11, 2021. With Cesar Elizarraraz in immigration detention, Mary said that living just down the street from the children has been a blessing, as it has allowed her to help her daughter care for her five kids throughout the COVID-19 pandemic. Photo by Camilla Forte/Borderless Magazine

A year after his return, Elizarraraz and Glauner had their first child, and the family continued to grow over the years. Glauner purchased a two-story brick house across the street from her childhood home with the help of her brother-in-law. Elizarraraz got a job working in the shipping and receiving department of a local distribution company five minutes from the house, and he often stopped by to spend his lunch breaks at home with the family.

Second Detainment

In September 2019, a 40-year-old Elizarraraz was arrested by Crystal Lake police on charges of possessing a fraudulent I.D., theft by deception and running an unlicensed car dealership. While trying to make some extra money buying, fixing and reselling used cars, Elizarraraz was accused of misrepresenting the condition of a vehicle in an online listing and rolling back the mileage on the vehicle’s odometer, according to police records. Elizarraraz denies these accusations.

After refunding the money for the vehicle he sold, Elizarraraz’s charges of possessing a fraudulent I.D. and theft by deception were dropped. He did, however, plead guilty to the unlicensed car dealership charge and was sentenced to supervision for a year and 30 hours of community service. Despite not receiving prison time, Elizarraraz was not released to his family after sentencing. Instead, he was transferred to immigration detention on Dec. 27, 2019.

“We waited outside the McHenry County Jail for two hours, and he never came out,” Glauner said. “The [criminal] lawyer was like, ‘OK, he should be out, you guys are good to go,’ and ICE had picked him up. He was given right over to them.”

Elizarraraz said that after being processed to be released from the county jail, he was told to wait and was then approached by an ICE officer and taken into immigration custody.

According to an ICE spokesperson, immigration authorities “encountered” Elizarraraz a day after he was arrested by Crystal Lake police in September. They reinstated his previous order of removal from two decades prior.

It is unclear exactly how Elizarraraz was transferred into ICE custody. According to Chief of Police James Black, the Crystal Lake police department does not ask for or check the immigration status of individuals with whom officers come into contact.

“There is nothing in the report that indicates we called ICE, interacted with ICE on the date of arrest, initiated any type of ICE detainer or even asked Mr. Elizarraraz what his immigration status was at the time of the arrest,” Black said in an emailed statement.

However, McHenry County Jail does not have the same safeguards between law enforcement and ICE. The jail is, in fact, contracted as a detention center for ICE.

McHenry County Sheriff’s Office Deputy Kevin Byrnes confirmed ICE was notified by the county jail almost immediately after Elizarraraz was arrested and put in jail custody in September 2019. Byrnes also confirmed that notifying ICE of an inmate’s outstanding immigration case is standard procedure for incoming cases to the McHenry County Jail. Such a procedure would likely be illegal under the pending Illinois Way Forward law.

Regardless of how he came to be in ICE custody, Elizarraraz experienced the majority of his detainment during a time when ICE was trying to reduce its population in response to the coronavirus pandemic. Immigrant detention centers, like prisons, have struggled with COVID outbreaks since the pandemic’s start. As of June 30, 2021, the McHenry County detention center had a total of 23 COVID-19 cases since early March 2020, according to data reported by ICE.

A New Administration

On January 20, 2021, a little over a year after Elizarraraz was detained by ICE, President Joe Biden was sworn into office. He immediately began actions to overturn Trump-era immmigration policies, signing an Inauguration Day executive order revoking former President Donald Trump’s Executive Order 13768. The directive called for the Department of Homeland Security to reexamine immigration policies and implement new policies that “safeguard the dignity and well-being of all families and communities.”

Despite the shift in policy, change was yet to be felt on the ground by families like Elizarraraz’s.

“We were hoping that they were able to maybe take individual cases like mine and just look at them a little deeper and say, ‘Man, this guy needs a chance to be with his family … while we await the adjudication of his case.’ That’s not just me, but other cases as well,” Elizarraraz said.

Then-acting DHS Secretary David Pekoske also issued a memorandum offering new interim guidelines for the department on January 20, 2021. In addition to implementing an immediate 100-day pause on certain deportations, the memo limited enforcement to “priority” cases defined as those immigrants who pose a threat to national security, border security and public safety. That is, cases with individuals suspected of terrorism, those apprehended at the border and individuals convicted of an aggravated felony.

Despite these policy changes, immigration legal experts like Lena Graber, senior staff attorney at the Immigrant Law Resource Center, argue that the recent guidelines actually criminalize non-citizens.

“Although it is a significant relief and a big improvement over the last administration, the Biden administration has really already dug in on this idea that immigrants could present some kind of threat to national security or public safety.”

A February 18 memo from Tae Johnson, then-acting ICE director, issued further guidance on enforcement protocols, stating that individuals would be considered a threat to public safety — and therefore a priority for law enforcement — if they were convicted of an aggravated felony or affiliated with gang activity. Johnson’s February guidance is currently in effect until new guidance is issued by acting ICE Director Alejandro Mayorkas.

How recently a conviction occurred is a factor for immigration authorities to consider when prioritizing cases, the memo noted. But some people have come to question how long those charges should still be applicable to current deportation cases like Elizarraraz’s.

“There are many, many people in the same situation as Cesar, who are facing deportation very often for mistakes … in the past,” said Fred Tsao, Senior Policy Counsel for the Illinois Coalition for Immigrant and Refugee Rights. “And so, we need to question to what extent it’s even fair to be imposing this additional punishment on individuals who’ve done their time, who’ve built lives since their release and who are trying to live their lives in the States.”

Despite his initial actions, the Biden administration’s stance toward immigration has not drastically changed from that of former President Trump. In her first trip abroad as vice president, Kamala Harris made clear that the current administration will not welcome undocumented migrants with open arms. “Do not come,” she said. On June 25, on a trip to El Paso, Texas, she explained that the administration instead wants to focus on improving conditions in countries with high immigration traffic, such as Guatemala, to reduce the number of undocumented individuals wanting to travel into the United States.

Although detention numbers initially declined under Biden, with 15,104 people detained nationwide in January 2021, they have since increased to 26,789 as of June 25. Furthermore, Congress is considering an immigration reform policy known as the New Way Forward Act that would disrupt the prison-to-deportation pipeline; however, the legislation is unlikely to be signed into law.

Locally, Illinois and Chicago have passed recent legislation limiting the way local agencies interact with ICE.

In February this year, the city issued an update to its Welcoming City ordinance prohibiting Chicago law enforcement agencies from participating in immigration enforcement operations and cooperating with ICE. Had this policy been implemented in Chicago’s suburbs, ICE may not have been made aware of Elizarraraz’s recent conviction in Crystal Lake, reducing the chances of him from being detained in the first place.

At the state level, a bill known as the Illinois Way Forward Act is now awaiting approval from Governor J.B. Pritzker. If signed into the law, cities and counties would be prohibited from entering into contracts with ICE to house immigrants in local jails. The act would also limit local law enforcement’s ability overall to collaborate with the immigration enforcement agency.

Immigration cases are complex, however, and it is unclear how the new federal and state guidelines would impact Elizararazz’s case if they were in place earlier.

According to an ICE spokesperson, Elizarraraz filed an appeal with the Board of Immigration Appeals that was dismissed on April 19, 2021. In another attempt to return to his family, Elizarraraz also filed a motion for Emergency Stay of Removal, but was ultimately denied May 21 earlier this year. Elizarraraz also pursued a U-visa, a type of visa that protects immigrant victims of crimes who cooperate with law enforcement. He was potentially eligible for the visa because of the drive-by shooting that happened in his youth, but ultimately could not apply for one because McHenry County Sheriff’s Office refused to sign the certification.

In the eyes of immigration authorities, Elizarraraz was still considered a priority for removal, despite the new and pending policy changes.

A Community Rallies

On May 18, 2021, McHenry County held a board meeting to vote on cancelling the county’s contract with ICE, which paid the county jail to detain individuals like Elizarraraz in ICE custody. Even though cancelling the contract could mean that her husband would be transferred to another facility, Glauner and her eldest son Isaiah still spoke out in favor of closing the detention center.

“For the last 20 months, I have been living a nightmare I don’t wish upon anyone,” Glauner said at the board meeting. “Our county should not be supporting these practices and profiting off the misery of those that are being detained or the family of those detained. These detainees are more than just $95 a day. They are someone’s spouse, mother, father, son, daughter, aunt, uncle, neighbor or friend.”

Before the meeting, a rally organized by the Coalition to Cancel the ICE Contract in McHenry County and other local activist organizations unfolded outside the jail. Looking out of the window, detainees — including Elizarraraz — could see the noise being made in their honor.

“It’s easy to lose hope in a place like that, but then, when you start seeing things like … the rally outside the organizations … you can just sense the hope that, ‘I’m not going to give up.’ There’s people out there that care about us,” Elizarraraz said.

The county ultimately voted to maintain its current contract with ICE, which will stand until the Illinois Way Forward bill is signed into law and goes into effect on January 1 next year.

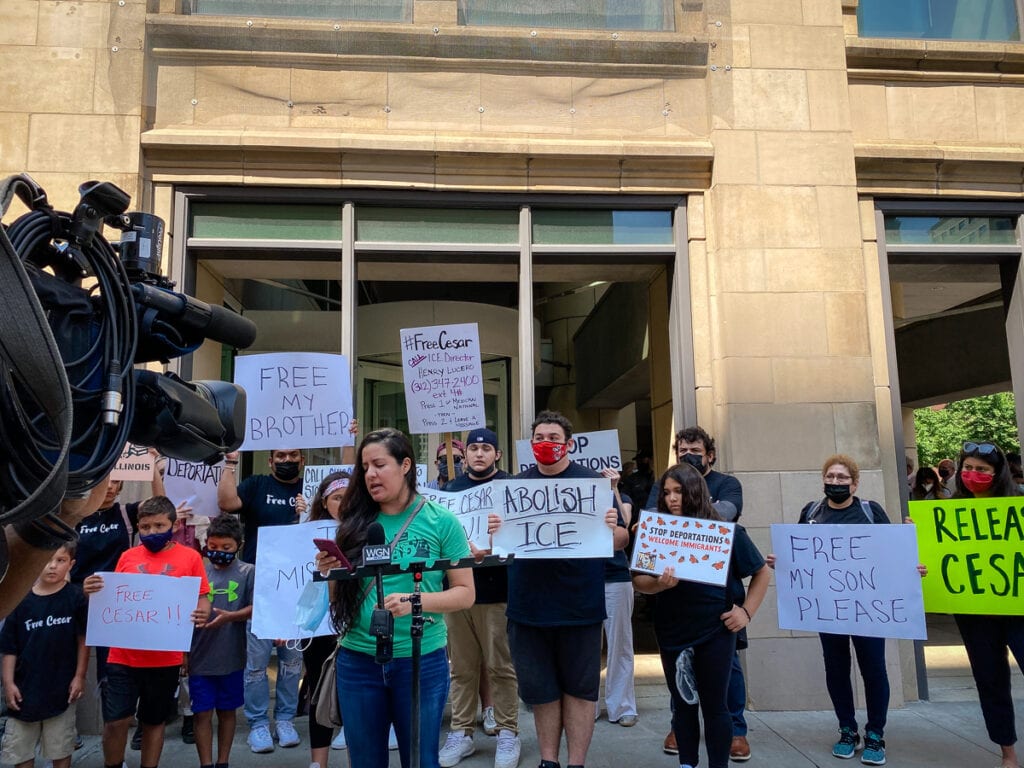

Xanat Sobrevilla speaks during a press conference outside of the United States Citizenship and Immigration Services’s field office to argue for Cesar Mauricio Elizarraraz’s release, on June 9, 2021 in downtown Chicago, Ill. Photo by Adriana Rezal/Borderless Magazine

Three weeks after the McHenry County board meeting, a crowd of about 25 people gathered outside the United States Citizenship and Immigration Services field office in downtown Chicago to advocate for Elizarraraz’s immediate release. Local organizations including the Illinois Coalition for Immigrant and Refugee Rights, Organized Communities Against Deportations and the Coalition to Cancel the ICE Contract in McHenry County held a press conference calling on Henry Lucero, ICE Enforcement and Removal Operations executive associate, to bring Elizarraraz home to his family.

“We need to see an immigration system that does not use criminalization of our people to excuse their actions, that criminal convictions don’t lead to automatic deportations,” OCAD organizer Xanat Sobrevilla, who helped organize the press conference, later said. “Cesar and his family demonstrate the detrimental consequences of that.”

Organizations and community members also circulated a petition calling for Elizarraraz’s release that gathered over 1,700 signatures.

Summer had just begun for the Elizarraraz family — the family’s second summer without their dad. At the press conference, 10-year-old Jocelyn held a large sign in front of cameras with the words “I MISS MY DAD.”

“Please allow him to continue fighting his case at home with his family,” Glauner said at the event. “Cesar should be seen as the loving adult that he is today versus the teenager he was once 20-plus years ago.”

Deportation Day

On Wednesday, June 16, Elizarraraz’s brother Arturo called the Mexican Consulate to find out if his brother was scheduled to be deported. The consulate confirmed that Elizarraraz was on the list to be deported for June 18.

A day later, Elizarraraz was denied the prosecutorial discretion his attorney, immigration lawyer Maria Baldini-Potermin, filed with the Chicago ICE field office on June 7.

Despite the news, the family, his attorney and local organizers refused to give up on Elizarraraz’s case. As news began to spread of his scheduled deportation, social media posts calling for his release circulated and organizers rushed to raise money for the family.

From inside the McHenry County detention center, Elizarraraz and his family began preparing their goodbyes. On Thursday, June 17, his extended family was scheduled to make nine video calls with him before being deported.

Before his first call, however, Elizarraraz found out from Glauner that immigration authorities had granted him a temporary stay of removal. On Friday, June 18, the day of his scheduled deportation, Elizarraraz was released to his family and put under electronic supervision. They were finally reunited one day short of 21 months of separation.

The family still doesn’t know why the stay was granted, or who granted it. But their lawyer Baldini-Potermin says that the public campaigns led by organizers were key to the decision.

Cesar Elizarraraz stands with a welcome message on the front porch of his home in Crystal Lake, Ill. on June 24,2021. Although reunited with his family, his case is far from over. Photo by Camilla Forte/Borderless Magazine

“There’s no measurement to describe the amount of happiness, the amount of joy that we’re having. Just being here with the kids, with Kristen — I’m still in shock, I’m still not believing it,” Elizarraraz said. “It’s the best gift I could have ever gotten — to be home with my family for Father’s Day, for [Kristin’s] birthday.”

At home, Elizarraraz wears an electronic ankle monitor as he sits at the dining room table holding Glauner’s hand. The kids can be heard playing in the backyard, sticking their faces into the window every now and then to ask their dad when he’s coming back outside. In the few days he’s been back, Elizarraraz has gone back to family bike rides, late movie nights and ice cream runs to the nearby CVS.

“For all the help that every single last person did out there for me, for the signatures, for the calls, and for whoever ultimately made the decision to allow me to be here with my family, I just want to thank them from the bottom of my heart,” he said.

Organizers say they will continue fighting for the right of Elizarraraz and others like him to stay. The passing of the Illinois Way Forward bill will not eradicate many of the challenges undocumented communities face, they say. Even when detention centers are no longer in Illinois, OCAD organizer Sobrevilla said ICE raids will continue and people can still be detained in other states, making it difficult for loved ones to stay in touch and for lawyers and organizers to advocate for cases.

“Our fights locally have been hard-fought and … long coming, but we’ll still be hurting if there’s no federal changes,” Sobrevilla said. “[Chicago’s] Welcoming City ordinance took five years, two mayors and even that was a struggle. Just recognizing that everyone deserves protections regardless of interactions with local police, or recognizing that policing is racialized and harmful — it hasn’t reduced violence in our communities. We’re seeking safety and healing.”

This week almost 160 organizations signed a letter criticizing the DHS and ICE for considering past criminal convictions as bars to immigration relief.

“There is no statistical correlation between citizenship or immigration status and proclivity to commit crime,” the letter said. “There is no evidence that detentions and deportations decrease crime or make our communities safer by any measure. There is myriad evidence, however, that detentions and deportations destabilize communities.”

Elizarraraz’s case is ongoing. He will meet with his case manager and case officer in Chicago on July 19. It is still unclear whether he will be allowed to stay in the United States, but he remains resilient.

“Mostly, I’ll just be spending time with family, taking one day at a time,” he says. “The fight’s not over yet.”

Clarification: This story has been updated to clarify the ownership of the family’s home and the fact that the court gave no official reason why it denied Elizarraraz’s Emergency Stay of Removal in May.