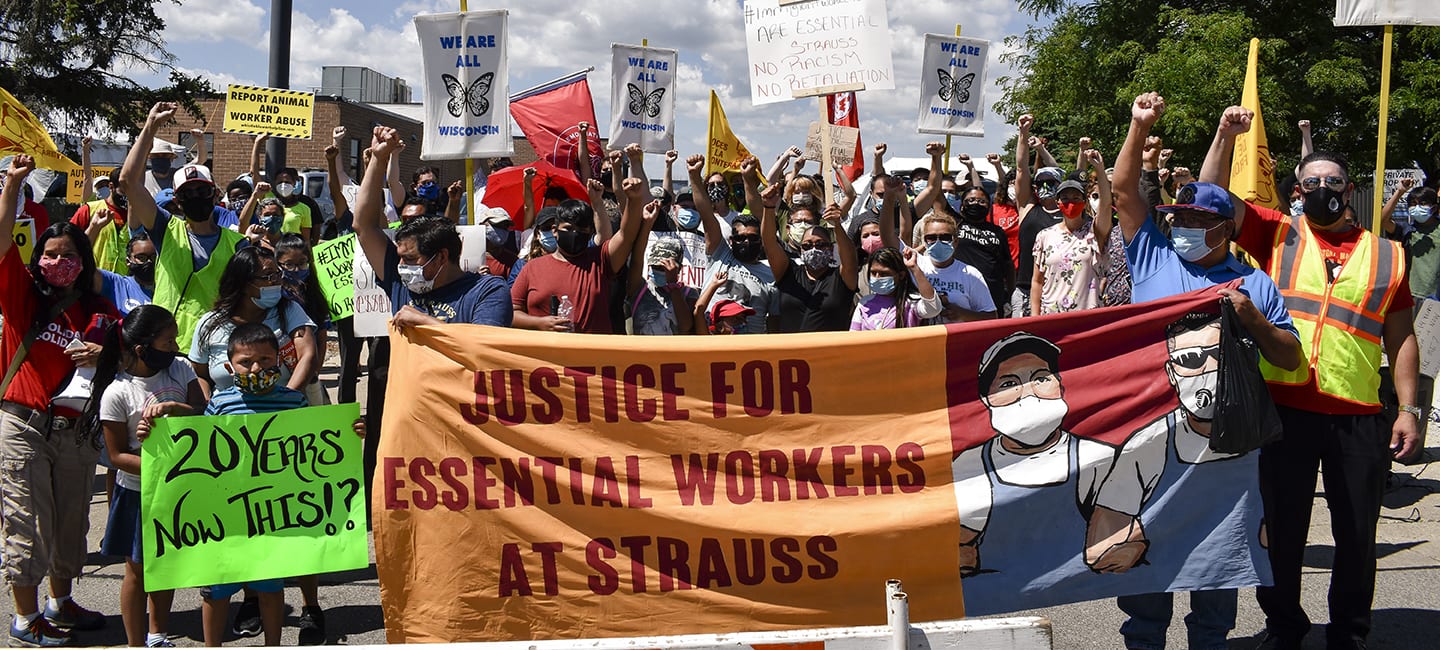

Francisco Velazquez/Borderless Magazine

Francisco Velazquez/Borderless Magazine Workers say they were fired after complaining about the lack of coronavirus safety measures. Over 17,000 COVID-19 cases have been reported among meat and poultry workers in the United States.

Above: About 60 demonstrators stand in front of the Strauss Brands, Inc. meatpacking facility before marching in Franklin, Wis. Aug. 7, 2020. Francisco Velazquez/Borderless Magazine

Strauss Brands, Inc.’s meatpacking facility is located a 20 minute drive from downtown Milwaukee. The first shift comes in at midnight and the second begins at noon during the day. Workers typically drive to the meatpacking plant at 5129 Franklin Drive in Franklin, Wisconsin in blue and grey colored trucks and SUVs, carrying their lunch in plastic bags.

In April six employees tested positive for COVID-19 and former workers allege Strauss put its entire workforce at risk by ignoring state mandated safety precautions to help slow the spread of the virus.

Twenty-nine employees anonymously filed complaints with the Occupational Safety and Health Administration about Strauss’ lax safety measures on April 22. These same employees allege they were then fired by Strauss on July 23 as retaliation.

Strauss claims the 29 employees were fired because their social security information did not match other tax documentation they had on file for them for the Internal Revenue Service.

Strauss notified one of its workers on July 23 that if they could not provide documentation that they were authorized to work legally or receive work authorization documents in the next 30 days the company would fire them, according to The Milwaukee Journal Sentinel.

Yet some of these employees had been working at Strauss for at least a decade without issue before they were fired in July.

Executive Director of Voces de la Frontera Christine Neumann-Ortiz and former Strauss Brands, Inc. meatpacking employee Maria Vasquez address a crowd of protestors during the Justice March for Essential Workers in Franklin, Wis. Aug. 7, 2020. Francisco Velazquez/Borderless Magazine

“OSHA was interviewing workers. That’s why we saw this as retaliation for demanding protections on the job, ” said Christine Neumann-Ortiz, Voces de la Frontera’s executive director. OSHA began an investigation into health and safety violations on June 2, 2020, according to OSHA records.

Strauss declined to comment when Borderless Magazine asked about the timing of the mass firings and the worker allegations that employees were terminated as retribution for the complaints they filed.

This isn’t the first time Strauss has been accused of being an unsafe place to work.

Strauss planned to move to Milwaukee’s Century Business park but withdrew the proposal in October 2019 after neighbors and a Milwaukee Common Council member opposed the project citing dangerous jobs that could lead to post-traumatic stress disorder among their concerns, according to The Milwaukee Journal Sentinel.

After withdrawing the initial project proposal, the company revised and resubmitted a new proposal in April of this year, with plans of beginning construction this fall.

In July 2017, OSHA fined Strauss for $5,000 for a health and safety violation. Strauss declined to comment on this violation.

Danny Alvardo, one of the 29 workers who filed anonymous complaints, stands outside of Strauss Brands, Inc. in Franklin, Wis. Aug. 7, 2020. Francisco Velazquez/Borderless Magazine

Danny Alvarado, 36, had worked at Strauss for 17 years when the coronavirus pandemic struck. He’s one of the 29 workers who filed the anonymous complaints with the help of Voces de la Frontera, a community based advocacy group safeguarding worker’s rights, about the lack of safety measures to slow the spread of COVID-19.

Alvarado and his coworkers allege Strauss did not follow any of the worker protections recommended by the CDC or OSHA: like staggering workers’ arrivals and departures, designating break times and encouraging workers to avoid carpooling to and from work.

Maria Vasquez, 41, is another worker fired by Strauss after filing complaints. She’d worked there for nearly 13 years and was the first person to test positive for the COVID-19 virus at the facility in April.

Vasquez, a single-mother of four, informed the company that she went to get tested on July 21. The company, however, did not inform her coworkers which put them at risk of being exposed to the virus.

Vasquez explained her recovery since contracting the virus has been different and challenging. She has slowly recovered over the past four months but still experiences body pain and has difficulty breathing.

Maria Vasquez and her family outside of their home in Milwaukee, Wis. Aug. 31, 2020. Francisco Velazquez/Borderless Magazine

“My biggest fear was my kids. ‘What were they going to do if I died?’ They would be without shoes, without food and possibly worse,” she said.

The company did not give her paid sick leave and she continued working though she was infected. Recovering from the virus is further complicated by burn injuries she suffered in 2014 while packing hamburger meat on an assembly line.

Vasquez still has bills piled up from the previous burn injuries and is fighting an ongoing court case against Strauss demanding that they pay her medical bills.

In Wisconsin, only 8.8 percent of confirmed COVID-19 cases among workers in five meatpacking plants were reported in April, according to CDC data. However, it is unclear how many workers at meat and food processing facilities may have been infected by the virus since data was last reported in April.

In Milwaukee, Latinos make-up only 15.4 percent of the population but make-up the largest number of confirmed cases, with an estimated 30 percent, according to data provided by the Milwaukee County COVID-19 dashboard, which is updated daily.

Wisconsin state orders have closely followed President Donald Trump’s executive order signed in April which ordered meat and poultry facilities to continue operating despite concerns about the virus.

After a public outcry over the firings their union negotiated for Strauss Brands to offer the fired employees a severance package worth over $264,000 on Aug. 6.

“When [employees are] fighting back, it’s not just the correct thing to do, but it’s like your fate is tied to one another,” Neumann-Ortiz said. “That’s why we encourage people to speak out, and to put a face to the movement. When they do, we actually see change.”

Voces has received 20 complaints from workers at other plant facilities in Briggs & Stratton and Echo Lakes Foods since mid-April. Those complaints include similar health and physical concerns to what the employees at Strauss complained about.

At Echo Lakes in Burlington, grandfather-to-be, Juan Manuel Reyes Valdez had been actively trying to force the company to implement these guidelines when he passed away.

At Briggs & Stratton, Mike Jackson, 45 and a father of eight, had been actively fighting and staged a walkout with co-workers before dying of COVID-19.

In both cases, the lack of paid sick days forced them to come to work while sick.

Racine Alderwoman Jennifer Levie during the Justice March for Essential Workers outside of Strauss Brands, Inc. in Franklin, Wis. Aug. 7, 2020. Francisco Velazquez/Borderless Magazine

An Aug. 7 protest in front of the Strauss headquarters also included support from elected officials and school board members like Milwaukee County Supervisors Steve Shea, Ryan Clancy, and Racine Alderwoman Jennifer Levie.

“I stand here in solidarity with these workers who are being treated incredibly unjustly. I call us to all stand together in this struggle to ensure that they are justly compensated,”Levie said, at the protest

It is a project of the Local Media Foundation with support from the Google News Initiative and the Solutions Journalism Network. The 19 partners span print, digital and broadcasting and include WBEZ, WTTW, the Chicago Reader, the Chicago Defender, La Raza, Shaw Media, Block Club Chicago, Borderless Magazine, the South Side Weekly, Injustice Watch, Austin Weekly News, Wednesday Journal, Forest Park Review, Riverside Brookfield Landmark, Windy City Times, the Hyde Park Herald, Inside Publications, Loop North News and Chicago Music Guide.