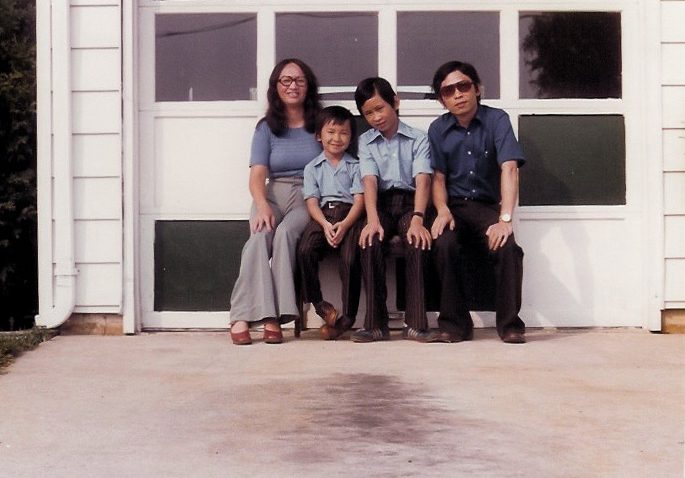

Photo courtesy of Viet Thanh Nguyen

Photo courtesy of Viet Thanh NguyenThe Pulitzer Prize-winning author of “The Sympathizer” will receive an award from the American Writers Museum in Chicago this month.

Growing up as a Vietnamese refugee in San Jose, California, Viet Thanh Nguyen felt a deep need to write in order to explore his family’s history and experiences.

The Pulitzer Prize-winning author was born in Ban Me Thuot, in the Central Highlands region of South Vietnam. After the fall of Saigon in 1975, his family came to the United States as refugees and eventually settled in San Jose, which is now home to more than 180,000 Vietnamese Americans.

News that puts power under the spotlight and communities at the center.

Sign up for our free newsletter and get updates twice a week.

Nguyen, a professor at the University of Southern California, received the 2016 Pulitzer Prize for fiction and other honors for his debut novel, “The Sympathizer.” He’s also published other acclaimed literary works, including two recent books, “The Refugees” and “The Committed.” In 2017, Nguyen was awarded a MacArthur Foundation Fellowship and Guggenheim Fellowship.

Later this month, Nguyen will accept the “Inspiring Writer Award” from the American Writers Museum in Chicago. He is donating the prize money to the Diasporic Vietnamese Artists Network, a group he cofounded that fosters literary voices in the Vietnamese diaspora.

Borderless spoke to Nguyen ahead of his visit to Chicago about growing up in San Jose and why refugees should have power over their own narratives.

You’ve talked a lot about growing up in San Jose, in a community of Vietnamese refugees. How has that shaped your view of what it means to be a “refugee?”

I grew up as a refugee in the 1970s and 1980s. And what that meant for me was that I saw my parents working relentlessly to carve out a life for themselves and their children and to send money home to Vietnam. I also saw the lives that my fellow Vietnamese refugees were living when the war was over, but so many of them seemed impacted by the legacy of the war, in terms of their memories and their feelings, and the way they acted out through trauma, melancholy loss and so on.

That time period really left its emotional imprint on me because I could see how the experiences of being refugees fleeing from war shaped so many people, not just in my parents generation who witnessed these things, but also my generation. Many of us didn’t witness these things, but experienced the emotional ramifications and ripples from what happened to our parents.

The experience left me with a deep empathy for refugees and immigrants and what they are going through. It also left me with an awareness that history had shaped my family, my refugee community and me. It gave me the sense that I needed to work through that history and try to understand it, which is what I do in my writing. And being a refugee also left me with the requisite emotional damage necessary to become a writer.

I think if I wasn’t a refugee, and didn’t feel that my emotional well being, my relationship to my parents and so on, had been fractured because of the many complexities of the refugee experience, I wouldn’t have the material and the motivation to write. So being a refugee is certainly a mixed blessing. I wouldn’t wish it on anybody. But I think the experience has left me with the empathy and the insight necessary to be a writer.

What kind of reactions do you get from Vietnamese American readers and refugees about your work? Do you feel like there’s a big difference generationally?

It’s hard to generalize a community like Vietnamese refugees, it would be like generalizing Americans. Americans have complicated feelings about my writing, some hate it, some love it, and there’s a whole range in between. So likewise, with refugees. “The Sympathizer” was written with what I think of as absolute authenticity, because I wrote it for myself.

I also wrote “The Refugees” for both myself and Vietnamese people because it’s about meeting these refugees. I was self conscious about Vietnamese reading the book, because I was self conscious about trying to represent them. And I felt that the book didn’t go far enough in terms of dealing with Vietnamese experiences and emotions and trying to represent the Vietnamese community.

I think a lot of so-called minority writers feel that sense of obligation, that given that we’ve been misrepresented so much by the larger community, we need to represent our own people. It’s a very noble ambition, but it’s also a flawed ambition, because I don’t think so-called majority writers feel that at all. I don’t think for example, white writers feel the need to represent anything or anybody but themselves for the most part.

In “The Sympathizer,” that was the position that I felt myself to be in. I was going to write about Vietnamese people, but I was going to write for myself, not for them, which means that the book has certain things that some Vietnamese people find to be very offensive.

The book is written from the perspective of a Communist spy. A lot of Vietnamese Americans are deeply anti-communist, and therefore refuse to read the book, and they think I’m a communist. The book is also very critical of communism. So the Communists in Vietnam think I’m very anti-communist, and the book is not allowed to be published there. And then there are some Vietnamese readers who think the book really does speak to their experiences, both younger and older Vietnamese people.

Why is it important for refugees to tell their own stories?

If we don’t tell our own stories, other people will tell stories about us. And often, that leads to misrepresentation and distortion or outright malevolence.

The very classification of refugees means partly that they cannot tell their own stories. They’ve been stripped of their identity, citizenship, nation and so on. People look down on them and treat refugees as objects to be spoken for or things to be spoken about. Refugees are treated as a crisis.

Read More of Our Coverage

Part of the irony of charitable or academic work about refugees is that even the people who are sympathetic to refugees can treat them as objects, speaking for refugees on their behalf. And so refugees absolutely need to be able to tell their own stories because they need to transform themselves from being objects in other people’s eyes into being the subjects of their own experiences.

In doing so, I think refugees can address this perception of themselves as being a crisis. I don’t think we have a refugee crisis. I think we have a systemic crisis of warfare, economic inequity, racism, xenophobia and a climate catastrophe that produces refugees. Refugees, if they can, can speak up for themselves to address this misperception.

You helped found the Diasporic Vietnamese Artists Network. Why do you think it’s important to bring together writers from the diaspora?

The roots of that organization are from my college days when I was hoping to be a writer.

I was looking around and I thought, wow, there are so many distortions and misrepresentations and stereotypes about Vietnamese people. It’s important that we have writers and artists, and my task was to become one of these writers. It was also to form a community of writers and people that supported writers so that there would be more and more opportunities.

Our challenge is to ensure that there is a diversity of voices speaking for us. And the reason why I think this is so crucial is because I have a certain vision of what I want to write about, and I think it’s legitimate, but I am well aware that there are many other kinds of perspectives in our community that need to be heard as well.

I’m also aware that I don’t even know what those perspectives are. In the younger generation below me, a lot of them don’t want to talk about the war, they don’t want to talk about the refugee experience. They want to talk about a bunch of other things, like vampires and trans possibilities. And so the creation of DVAN is partly to ensure that we give these opportunities to younger writers, and in the unpredictability of what they’ll come up with, they will transform the perception of Vietnamese Americans and the Vietnamese diaspora.

We’re witnessing two major refugee waves, with the situation in Afghanistan and Ukraine. There are also millions of other displaced people due to conflicts that don’t receive as much attention. What do you see as your role as a refugee storyteller – and what are the limits of that position?

The role and the limit are related, which is that refugees who can speak for themselves, find themselves in the same trap that other so-called minorities have found themselves in.

Which is that we’re only expected to speak about our personal experience. We are expected to be eyewitnesses, but only to our particular history. Our trauma and our story is used as evidence for charity and to create sympathy to take in more refugees. That’s all that’s expected of us.

And if we do that, we become professional refugees, or professional minorities of whatever background, and it’s very highly marketable. It doesn’t allow us to say that refugees have been with us in the past and refugees will be with us in the future, because of the systemic crisis of warfare and colonization that I already mentioned.

What we see is not an Afghan crisis or a Ukraine crisis but a crisis of imperial conflict. That’s a very different analysis. What we see is that refugees, in these cases, are being manipulated to fulfill the particular ideological narratives of the West. That’s going beyond what we’re expected to say.

Read More of Our Coverage

The pathway for Ukrainians to go to other countries is relatively easy. I mean, tens of thousands of Ukrainians have been admitted to a number of different countries.

The pathway for Afghans is much, much harder, on the scale of hundreds or thousands. And so, the way we as refugees solve our problem of being invited to speak, is to speak on our terms. So that we can say things like, “We are here, not because of the crises of our countries, Afghanistan, Ukraine, Vietnam, but because you, you who have invited me to speak, are part of countries that have fought wars or encouraged wars in our countries.”

The empathy the West feels for Ukraine right now, is very important, but also completely hypocritical and highly selective, and doesn’t extend equally to Afghans. It doesn’t extend equally to understanding that many of the things that we, the West, accuse Russia of doing, the West has already done and is doing now. And people who invite refugees to speak often do not want to hear this kind of analysis.

This interview has been edited and condensed for length and clarity.