Max Herman/Borderless Magazine

Max Herman/Borderless MagazineThe eviction case comes as Chicago migrants are facing a triple crisis – homelessness, food insecurity and increased deportations under Trump.

When Yusmary* was first invited to “the Orphanage,” she thought she had finally found a safe place to rebuild her life.

“The Orphanage,” a nickname for a former church building in Chicago’s Bridgeport neighborhood, was well-worn, but it had a kitchen, bedrooms and accessible showers — things she didn’t have at the crowded, city-run migrant shelter in nearby Pilsen where she stayed with her husband and three kids. At its peak, the former warehouse turned shelter in Pilsen housed over two thousand migrants, a fraction of the over 51,000 migrants who had come from the southern border to Chicago since August 2022.

Yusmary found sleeping difficult in the Pilsen shelter and feared for her family’s well-being. A December 2023 investigation by Borderless found that the shelter had freezing temperatures and unsanitary bathrooms. The food the shelter workers gave them was sometimes spoiled, migrants told Borderless at the time, and chickenpox and the flu spread quickly. Just days after Borderless published its 2023 investigation, a five-year-old boy at the shelter fell sick and died.

News that puts power under the spotlight and communities at the center.

Sign up for our free newsletter and get updates twice a week.

“We were living with constant sickness,” Yusmary said of the city-run shelter.

But she said things shifted when she met a mutual aid worker outside the Pilsen shelter. The worker invited her to visit “the Orphanage,” where she could shower and eat a meal.

Yusmary immediately saw the potential in the space. She asked if she could start cooking meals — warm Venezuelan food — in the building for migrants like herself. She aimed to give them a taste of home and an alternative to food distributed at the city-run shelters. El Comedor Comunitario — the Community Kitchen— was born.

Chicago has a rich history of mutual aid work supporting immigrants. During the COVID-19 pandemic and the peak of the migrant buses coming to Chicago from Texas, such community-based networks helped fill critical gaps in government assistance and charity efforts by connecting people to food, clothing and housing.

El Comedor stood apart from many of these mutual aid efforts as a community kitchen run by and for migrants. At its peak, El Comedor served free, hot meals to migrants and those in need twice a week, gave out free clothing and offered a safe space for migrant children to play. The self-organized group also provided free housing to migrants during the city’s greatest homelessness crisis in a decade.

But the sale of First Trinity Lutheran Church, the home of “the Orphanage,” has changed everything.

Read More of Our Coverage

Migrants involved with El Comedor told Borderless they were asked to leave the building in March. They say they knew the building had been sold but were blindsided to learn they had to go so quickly.

“There was going to come a time when we had to leave,” Linares*, one of the cooks, told Borderless. “I mean, this was sudden.”

The eviction comes as tens of thousands of migrants who arrived in Chicago over the last three years are facing a triple crisis – homelessness, food insecurity and increased deportations under President Donald Trump.

Food That Tastes of Home

El Comedor was born during a different crisis: In October 2023, nearly 4,000 migrants who had been bused to Chicago during “Operation Lone Star” were sleeping in the lobbies of police stations across the city. The operation was an attempt by Texas Gov. Greg Abbott to pressure the federal government to enact stricter immigration policies.

“We were the first to open our doors to the migrants and they’re still coming. And we have not turned them away,” Chicago Police Superintendent Larry Snelling told the Associated Press on Oct 17, 2023. “But what we need are other people to step up in these situations because the burden has been on the police department to house people.”

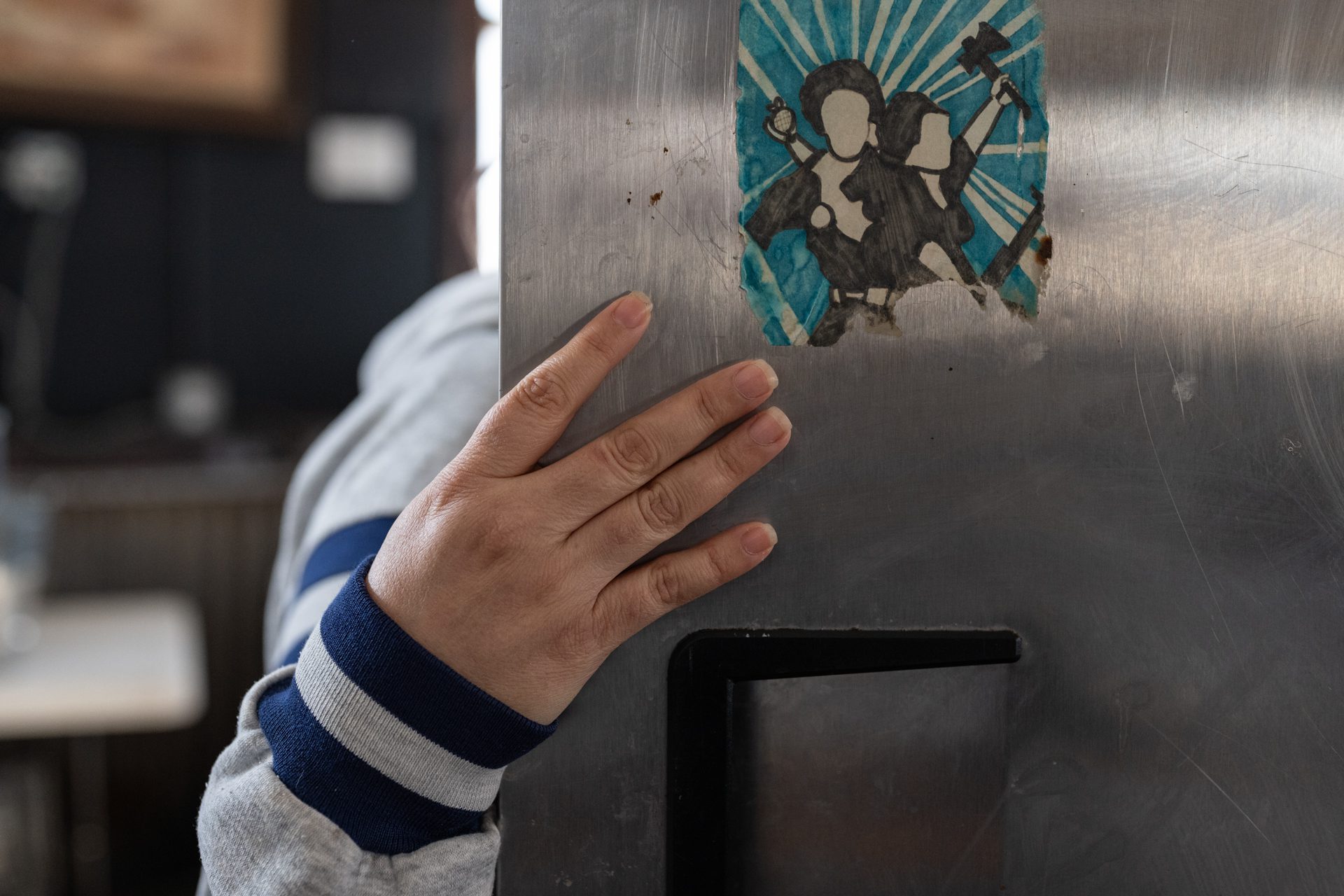

At the time, individual volunteers and mutual aid groups were already working with migrants, providing urgent medical care and handing out sleeping bags and sandwiches. “The Orphanage” became a natural home for some of this mutual aid work. Midwest Books to Prisoners, a nonprofit organization that sends literature to prisoners across the country, worked out of the building, and other groups regularly hosted concerts and community events. Once Yusmary connected with “the Orphanage,” community members stepped up to provide El Comedor with the ingredients for meals.

Depending on what ingredients they were given, they might cook arepa – a flatbread popular in Venezuela – stuffed with cheese, black beans or chicken. In a huge metal bowl, they might make ensalada de payaso (clown salad), with beets, tomatoes, onions and carrots. Other times, they might make banana milk or chicken soup.

Word of the community kitchen quickly spread among Chicago’s migrants, most of whom came from Venezuela and were hungry for food that tasted of home. Some were staying at the city-run migrant shelters, like the one in Pilsen, which were spun up to move migrants out of police stations.

El Comedor fed them on Tuesdays and Saturdays on folding tables in the community center’s main room. As the city moved migrants from police stations to city-run shelters to subsidized apartments or homeless shelters, “the Orphanage” also began acting as a shelter for migrants. Some migrants were able to get work permits, others were not. Many struggled to get the regular paychecks necessary to rent an apartment in Chicago. So while they worked, applied for asylum, and looked for a place to live, “the Orphanage” gave them a stable home.

“It’s not easy to work here,” Yusmary said. “You need courage, you have to have faith. You go out, you look, but without papers, it’s very difficult to get a job. And there are times when you do get a job, but it is very, very complicated.”

With the election of President Trump and threats of mass deportations, El Comedor changed again. Many migrants were afraid to go out, and El Comedor slowed down its meal program. They made boxed meals that migrants could eat wherever they were living. They were also hired by another mutual aid group to cook food that could be given away in community fridges.

Caught in the Middle

As El Comedor was evolving, things were also changing at “the Orphanage.”

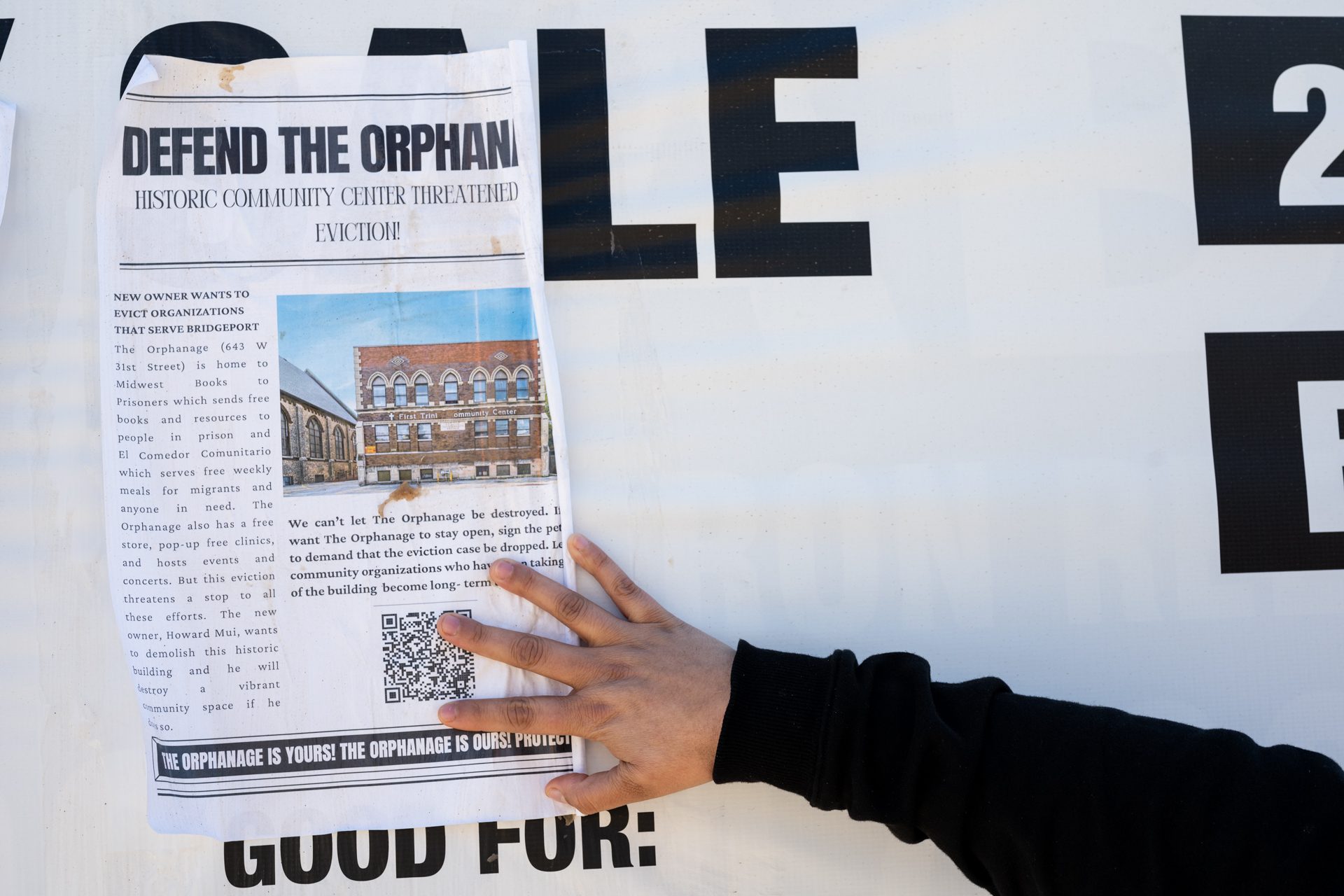

The First Lutheran Church of the Trinity property was sold in June 2024 to developer Howard Mui for $1.1 million. Soon after, Mui’s attorney sent a 30-day notice to those living in the property to leave by Aug. 1, 2024.

Eviction court records show that a Windy City Process Serving agent successfully gave the 30-day notice to “Jeremy Hammond” (sic) on June 27, 2024. Additional documents submitted to the court by Mui’s attorney show a “Co-working Space Agreement” between Jason Hammond of Midwest Books to Prisoners and Thomas Gaulke of First Lutheran Church of the Trinity for the nonprofit organization to use the former church space. However, Gaulke denied signing the agreement in a conversation with a church representative, according to a notarized certification from the representative in court filings. Gaulke did not respond to Borderless’ requests for comment, and Hammond declined to go on record for this story.

After residents did not leave, Mui’s lawyer, Nicholas Frenzel, filed a complaint in eviction court on Aug. 2, 2024, asking for possession of the building. Frenzel did not reply to requests for a comment.

The eviction court process has been confusing for the El Comedor migrants, who are unfamiliar with the U.S. court system and mostly do not speak English. The migrants told Borderless they did not know about the ongoing eviction case until the same process-serving agent returned on Jan. 27, 2025, and gave a court summons to one of the migrants, who passed it on to Hammond.

Migrants told Borderless they had hoped to stay at the building until August 2025, as they were told that was the previous owner’s rental agreement date. While the eviction case is not over, the judge told Borderless that a settlement is close. The details of the proposed settlement are not public, but the eviction is expected to move forward. El Comedor’s team will soon need to find a new place to live and cook.

“There is No Guarantee of Anything”

Amid the uncertainty at El Comedor and deportation threats from the Trump administration, Yusmary is questioning whether she and her family should stay in Chicago.

“It is something that I believe that of the 100% of Venezuelans who have come to the United States, 90% want to return,” Yusmary said. The news of Venezuelans being captured by Immigration and Customs Enforcement agents and put on a plane to El Salvador shook her, she said.

“There is no way I want to stay here in the United States, and even less now with this situation,” Yusmary said. “We do not know what country they are going to send us to tomorrow, what ideas this President has in mind to say: Venezuelans are now like a military target for Donald Trump. What is going to happen tomorrow?”

Yusmary owned a small business in Venezuela that sold school supplies. She fled the country when her business failed and she faced extortion amid Venezuela’s sociopolitical crisis. But she says she is willing to risk being harmed by returning to Venezuela because of the current political shift in the U.S.

“There is no guarantee of anything at this time,” said Yusmary, who applied for a work permit and asylum but has yet to receive either. “I say almost every thought is to try to make some money, collect at least what we spent coming and head back to Venezuela.”

Her fellow El Comedor chef, Linares, has gotten a work permit. But Linares, a police officer in Venezuela before coming to Chicago with her wife, says she, too, is contemplating returning home.

Linares says they were both trying to make ends meet – working alongside Yusmary until 3 a.m., juggling a side gig at an “arts and crafts” manufacturing company, where they make personalized cups and notebooks. They hoped to send money to their family back home.

Now, their dreams lay shattered.

“We feel like we hit a brick wall,” Linares said.

A 2024 survey conducted by NORC at the University of Chicago found that Chicagoans are more likely to want immigration reduced and more likely to support the deportation of undocumented immigrants than Americans in general.

The same survey found that half of Chicagoans think the city is not doing a good job of taking care of migrants, particularly when it comes to housing and job placement. Two and a half years after the migrant buses started coming to Chicago, community members are still stepping up to fill in the gaps.

On May 1 evening, a crowd streamed into a dive bar in the Logan Square neighborhood to attend a concert billed as “Chicago’s Premier Anti-Fascist Rock and Roll Experience.” A local German soccer team fan club, FC St. Pauli Chicago, had organized a night of music and raffles to raise money for El Comedor. The migrants continue to collect donations through their Venmo account @comedor-comunitario-chicago and hope to raise enough to find a new home.

“We’re a bunch of random people who come together to watch soccer for a German football team, but we’re coming together because we have shared values,” said event organizer Brad Thomson. “We’re here to stand up not just for the recently arrived migrants from Central America, [but] from South America, and other regions.”

Despite everything against them, El Comedor’s migrants are still fighting for their community, and their community is still fighting for them.

They told Borderless they want to continue reminding Chicagoans of Venezuela’s ‘seasoning.’

“That’s how we got our start,” Yusmary said. “We did everything, but with our flavors.”

*Borderless is not using the full names of migrants involved with El Comedor at their request and due to concerns about their safety.

Contributing reporting from Oscar Gomez.