Cori Lin for Borderless Magazine

Cori Lin for Borderless MagazineMany students face canceled visa interview appointments, months-long waits and unexplained rejections, jeopardizing their attendance at American Universities.

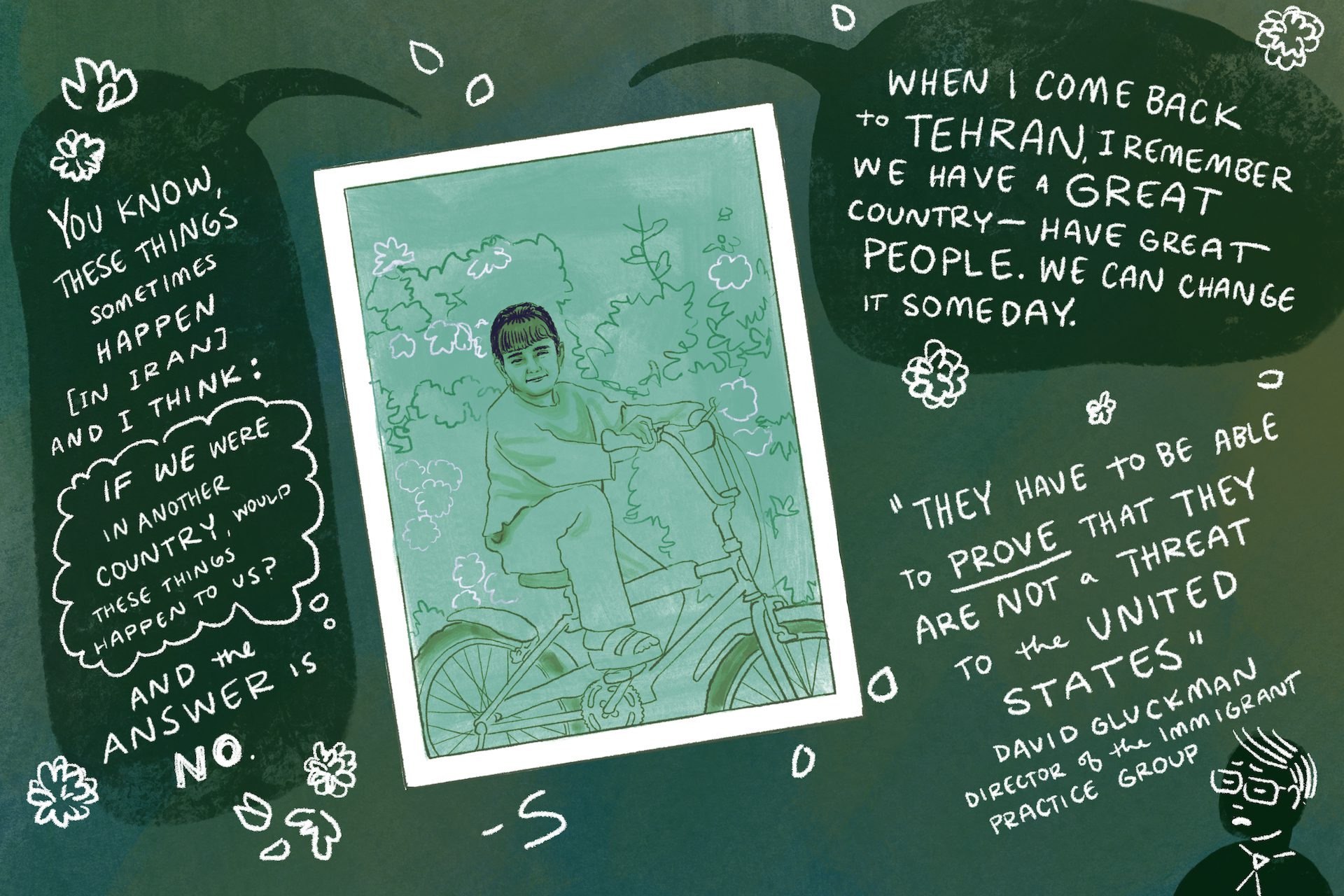

After flying from Tehran to the U.S. embassy in Armenia, S., who asked to remain anonymous to prevent disrupting her current visa application, froze as she met the immigration officer’s eyes and heard, “I’m sorry, your visa application has been denied.”

Surely, she misheard.

I spent eight months preparing for this moment. She had filed stacks of paperwork, taken necessary tests to ensure she met U.S. university requirements, made appointments months in advance and saved thousands of dollars to cover her visa expenses and travel to Armenia. It is unknown why she was denied.

News that puts power under the spotlight and communities at the center.

Sign up for our free newsletter and get updates twice a week.

“You’re thinking – ‘Oh, God. Eight months and where else [can I go now] with this rejection in my case, that …doesn’t have an explanation,’” said S., who was admitted to a university in California to pursue her Ph.D. in biophysics. “[The agent] just says go and come back another day. She doesn’t even know how much it took for us to take the time. And how much we spent to be in Armenia. How much we spent preparing this? She didn’t even look at my documents.”

The visa denial came at the heels of a tumultuous few years that included the death of her sister and a severe case of COVID-19 that left her mother hospitalized. S. felt the need to pause her applications. This was her third attempt.

Many Iranians are struggling to navigate the increasingly stringent screening process for student visas amid long-standing sanctions. With no U.S. embassy in Iran, students travel to neighboring countries for visa appointments, only to be canceled or immediately rejected by agents with no explanation. Nearly 10 Iranian students who spoke to Borderless Magazine this summer described the visa screening process as difficult or almost impossible.

The stringent screening process continues amid a divisive presidential election where immigration has become a top issue for voters. Former President Donald Trump and Vice President Kamala Harris have each faced criticism handling immigration issues. During his first term, Trump issued a travel ban for people traveling from seven Muslim countries including Iran. If re-elected, he reportedly said he would bring back a ban “even bigger than before.” Since 1980 and especially after 2001, Iranian migration to the U.S. has decreased significantly.

Read More of Our Coverage

Policy changes brought on by the Islamic Revolution of 1979 sparked an increase of Iranian students to flee the country and pursue higher education in Europe or the United States. A year later, Iranian universities closed for three years to revamp curricula reflecting Islamic values as part of the Cultural Revolution.

In 1980, more than 51,000 Iranian students were studying in the United States. The number has seen a precipitous decline after the deterioration of political relations, according to the Institute for International Education. Now, Iranian students are among the largest population in the Middle East who travel to the United States for an American education. In 2023, more than 4,000 students traveled on an F-1 student visa.

Still, these students face an arduous process of long waits and canceled appointments that leave their educational trajectory in limbo.

“You know, these things sometimes happen, and I think if we were in another country, would these things happen to us? And the answer is no,” said S.

Backlog and stringent visa screenings

Some legal advocates blame these cancellations on Section 306 of the Enhanced Border Security Act, which requires countries labeled State Sponsors of Terrorism to follow special procedures to get a visa. This policy, which started after Sept. 11, 2001, created additional hurdles for citizens from Syria, Cuba, Iran and North Korea.

According to Section 306, residents of these countries over 16 years old must appear for an interview and additional checks with an office to prove they don’t “pose a threat to the safety or national security of the United States.” Such screening prolongs the visa application process and can take nearly a year, according to some students.

This often requires travel and makes it easier for officers to deny students, as noted by David Gluckman, the Director the the Immigration Practice Group at law firm McClandish Holton in Richmond, Virginia. He has worked with thousands of clients from Iran facing unreasonable delays as they await visa decisions.

Section 306, he said, allows the consular to put applicants under administrative processing, which often requires additional security clearance like background checks and security advisor opinions to ensure they are not threats to national security.

“They have to be able to prove that they are not a threat to the United States,” Gluckman said. “You have to overcome that presumption. That determination is not made by the consular office on the spot. It is something they need to submit to people in D.C.”

Read More of Our Coverage

He added that only citizens of “state sponsors of terrorism” must face administrative processing. This process makes it difficult for applicants to know the status of their visa and whether it has been approved.

“If you’re in administrative processing, there’s really no way to know what’s going on with your case,” he said. “There’s really no way to know when it’s going to be completed. The only thing you can do to prepare yourself is No. 1: Apply early. No. 2: Be as forthcoming as possible with the information the particular consular officer is asking from you.”

Gluckman said a major issue with administrative processing is a general lack of resources to handle a backlog of more than 50,000 awaiting visa decisions. He estimated that only around 30 analysts are reviewing them.

“There are so many cases in the queue and only so many people to work on them,” he said. “It seems to be a big time resource issue at the moment.”

And once the applicant receives their visa decision, if they are denied it is nearly impossible to reapply.

“The problem is that once the decision is actually made by the consular officer to refuse your visa on the basis of these terrorism routes, it’s almost impossible to challenge it,” Gluckman said.

“They have to be able to prove that they are not a threat to the United States. You have to overcome that presumption.”

Advancing skills abroad

After the Revolution in 1979, the U.S. closed its embassy in Iran. Even 45 years later, students were forced to travel to neighboring countries like Armenia, Dubai or Turkey for their visa appointments. It’s typical for some students to lose their jobs or university admissions offers in the U.S. while waiting for their appointments.

Those who successfully made it to the U.S. described shared struggles and adversities they overcame, including challenging the visa process to move out of Iran and the narrow job prospects they felt were holding them back.

After getting her visa in Turkey, Elnaz Nour moved to California in December 2020. Nour, a medical researcher, got her medical degree in Iran. She noted that she didn’t feel like she had an opportunity to make a change there.

“There weren’t sufficient resources like facilities, cutting edge technology,…Internet connection or access to different websites,” she said. “It was really hard to find what you love because of a lot of sanctions. Because of [the lack of] technology and modernity, you weren’t able to pursue all you wanted to do.”

Read More of Our Coverage

Her story is similar to that of others who faced few educational options and struggled to obtain a student visa. In September 2020, Sina Taamoli arrived in the U.S. to pursue a Ph.D. in physics and astronomy at the University of California, Riverside.

Throughout his bachelor’s in Iran at the renowned Sharif University of Technology, Taamoli pursued mechanical engineering — a decision he believed to be a “safe choice.” Those who join their university’s engineering programs are typically more successful in the job market than those who study pure sciences like physics, chemistry, or mathematics because of Iran’s industry, Taamoli said.“Most of my family members were highly educated, and most of them were doctors – medical doctors,” he said. “Having a high level of education was just a predefined goal in my mind since my childhood.”

Many Iranians face cultural pressure to prioritize education, especially graduate and doctorate degrees. Even while education is emphasized, Taamoli said it’s challenging to change your educational path after selecting your major.

“If you don’t make the right choice, it might result in a disaster in your life and it’s sometimes hard to compensate for a bad decision in high school in changing your major,” he said.

After receiving his bachelor’s degree in mechanical engineering, Taamoli re-entered Sharif University to pursue a Master’s degree in his true passion—physics. He later applied for PhD programs across the United States to escape a deteriorating economy in Iran.

“Everything was getting worse year after year in Iran, and I had to make this decision,” he said.

“Everything was getting worse year after year in Iran, and I had to make this decision,” he said.

Like other students, Taamoli also faced financial hurdles and discrimination when applying for his student visa. As he studies in the U.S.

He said he has bonded with his community of Iranians in the U.S. who have similar experiences. He noted that coming to the U.S. was less of a choice and more of a necessity.

“The only thing that could help at this moment would be having your friends around – people who are experiencing the same emotions at the same time.”

Despite the economic and political instability, students like S. who are still trying to leave Iran remain hopeful, both for the future of their country and for themselves.

Months after the rejection, S. replays the moments leading up to her appointment and remains confused about the lack of explanation for her rejected application.

I graduated from Tehran University in 2020 as a medical doctor and began working as a clinical researcher. She dreamed of coming to the U.S. because Iran lacked facilities and resources that could sustain the work she wanted to do.

She is motivated to continue applying to one day offer affordable and efficient medical care to her patients, something she says is largely unavailable in Iran due to sanctions and the worsening economic and political climate.

“I’m thinking of my patients,” she said. “I’ve promised them I’m going to make this possible one day, and I will make it possible.”

After recently returning from Armenia, S. hopes to receive another appointment to get her visa and eventually come to the U.S.

“When I come back to Tehran, I remember we have a great country – have great people,” S. said. “We can change it someday.”