Max Herman/Borderless Magazine

Max Herman/Borderless MagazineAlthough tensions have flared throughout the humanitarian crisis, Black and Brown leaders see an opportunity to unite and advocate for Chicago’s South and West Sides.

Just the mere mention of migrants ignited a fall town hall meeting hosted by Congressman Jonathan Jackson (D-IL) at South Shore Cultural Center. Agitated murmurs filled a packed room as residents took turns expressing a wide range of heated frustrations: They included perceptions of a Black community being passed over in favor of assistance for noncitizens; feelings that Black migrants are not getting as much help as migrants of other ethnic groups; and suspicions that a welcoming mat now will lead to diluted Black political power down the road.

The embittered mood mirrors many others in both Black and Brown communities throughout the city.

If fostering political division between and among Black and Brown communities was one of Texas Gov. Greg Abbott’s goals in his monthslong chaotic effort to offload asylum-seeking migrants to sanctuary cities like Chicago, it’s working.

Want to receive stories like this in your inbox every week?

Sign up for our free newsletter.

“Unfortunately, Black and Brown people are taking the bait,” said the Rev. Kenneth Phelps, senior pastor of Concord Missionary Baptist Church in Woodlawn. “It’s not just a feud; we’re seeing it right before our very eyes. The tensions are real.”

When the city turned the former Wadsworth Elementary School into a migrant shelter — instead of a job training center — without community input, it stung. Community members felt overlooked and disrespected again when local businesses and organizations did not get the opportunity to bid for contracts tied to the response.

“We, too, were a little bit angry with how the city was handling things,” according to Phelps, who acknowledges the complexity of it all. “ But for us, [the migrants] were helpless. They were hungry, they were hurting, and they were human. So we decided to take another tack, as opposed to protesting their presence, we decided to welcome them and approached the city, you know, and said, ‘How can we help?’”

Residents in historically under-resourced communities have witnessed the power of local, state and the federal government respond decisively to the emergency caused by the arrival of asylum-seeking migrants. More than 39,000 migrants, who largely hail from Venezuela, have been transported from Southern states by buses and planes since August 31, 2022. Many have no papers, no homes and no jobs — just the perilous vulnerability of life in limbo. The City of Chicago has spent over $300 million since 2022 for emergency shelters and other services.

In Black and Brown communities throughout the city, tensions have boiled over in response to these efforts to leverage available resources, particularly federal American Rescue Plan Funds allocated in 2021 to address the economic fallout of the coronavirus pandemic. In public forums, social media and private spaces, when residents compare the assistance given to asylum seekers with yearslong requests for community investment, they are clear about one thing: They want their lives to be treated as an emergency, too.

These emergencies include everything from food insecurity and life expectancy gaps linked to racial and ethnic segregation to access to affordable rents and fairness in home mortgages.

Several data points back this up:

- A third of Chicago metro Black and Latino families with children experience food insecurity and hunger, twice as much as white families, according to the Greater Chicago Food Depository.

- Chicago has the largest gap in life expectancy, 30.1 years, linked to racial and ethnic segregation, according to a 2019 report from researchers at the NYU School of Medicine.

- The pandemic left a mark: Black life expectancy dropped below 70 years old for the first time in decades, according to a 2022 City of Chicago report.

- Latino residents experienced a seven-year life expectancy drop from 2012.

- For the first time in decades, life expectancy for Black residents of Chicago fell below 70 years.

The coronavirus pandemic put into stark contrast a lack of community investment, and before leaders had time to address those gaps, the migrant crisis arrived on Chicago’s doorstep. After seeing the speed and focus applied to the migrant crisis, many residents in under-resourced areas are demanding action and attention like never before.

“It is inhumane to not want to have compassion,” said Leslé Honoré, CEO of Urban Gateways, a youth arts education organization and co-chair of Elevated Chicago, which promotes equitable development around public transit. “But it requires us to be thoughtful and understand who we are asking compassion from and where their capacity is to give that it is a conversation that we need to continue to explore. I wish that people would see that our oppression all comes from the same place and there’s power in unifying.”

During a public comment period at a recent Chicago City Council Committee on Immigrant and Refugee Rights meeting, resident Anthony Hutt called on city officials to “undergo a profound transformation” that recognizes the dignity of everyone, regardless of background.

“We must not continue to ignore the cries of those who are unjustly marginalized and disenfranchised,” he said. “We must strive to create a city where every person has access to quality education, affordable housing and meaningful employment.”

Not every sentiment about the crisis has been generous. Some of the negative opinions about migrants and the legality of them being here are powered by misinformation, such as the extent of the help migrants are getting. But amid false rumors is a universally felt truth among some people that they’ve never gotten any help, so why are these people getting so much, according to Juliet de Jesus Alejandre, executive director of Palenque LSNA.

There are also the truths that hurt, including the fact that many asylum seekers are getting assistance to secure work permits when undocumented residents have long hoped for this opportunity.

“The truth is some people [are] getting work permits,” De Jesus Alejandre said. ” And for a lot of our leaders, a lot of them are Mexican women who’ve been here 20-30 years undocumented that is painful to think, “Damn, they’re gonna get a work permit? It’s not citizenship; it’s not the thing they’ve been there for, but it is one step closer to [being] able to live more sustainably and with some stability with some peace of mind.”

Read More of Our Coverage

De Jesus Alejandre also adds: “Let’s do some myth-busting. Like what are people actually getting? Because they’re not getting $7,000 and new cars,” as one Uber driver told her once.

Lesson learned: ‘You can’t stop organizing’

Sylvia Puente, president & CEO of the Latino Policy Forum, acknowledged the tension between Black and Latino communities on this topic and the emerging tension between long-term undocumented residents and new migrants. But this crisis has also presented an opportunity for Black and Brown leaders to present a united front for their respective community needs.

Notably, Chicago has always been an immigrant-friendly destination, according to Jaime Dominguez, an associate professor of political science at Northwestern University. Unlike other cities, immigrants have not been as radicalized or demonized as other places that don’t have that long history of immigrants being part of the governing apparatus, like Los Angeles or New York.

In the 1980s, Black and Brown communities came together on the issues of representation, according to Dominguez. Despite the growth in the Latino population, they didn’t have one representative whatsoever on any level of city government in 1980.

“It was actually the election of Harold Washington in ’83 and in 1987 that really forced the communities to really come together,” Dominguez said.

The realization that collective effort can yield results or at least make communities heard by elected officials might be the ultimate takeaway from this crisis, according to several community leaders.

On issues like housing, mental health care and food insecurity, the crisis has created “a more proactive response” to these issues, Puente said. She points to the City of Chicago’s effort to integrate migrant and housing services, and overhaul tax increment financing (TIFs) and instead borrow more than $1 billion to invest in affordable housing and other projects.

And it’s not lost on community leaders the inequity of extending work permits to recent migrants but not undocumented residents who still volunteer with organizations like The Resurrection Project to help migrants.

“That’s a whole other angle that we’re trying to navigate,” said Puente, who said Latino community leaders are asking the mayor, the government and President Joe Biden’s administration to do more than address short-term migrant issues but offer solutions for long-term migrants.

At the heart of this united front is community organizing, said De Jesus Alejandre, who notes that it’s not enough to marshal voters to elect a progressive mayor like Brandon Johnson and then leave it to him to implement policies that bring equity to marginalized communities.

“You can’t stop organizing,” she said.

“We’re just trying to figure out in community and in movement spaces and with our relationships with a mayor and all his affiliations, how do we continue to not only co-govern … when it even may feel very uncomfortable. Our job is to be organizers and to continue to say, ‘But what about? And how? How do we do this?’”

Equity is the only side to be taken

Community-based efforts and grassroots organizing showcase what happens when institutions focus on who needs help most. Public outcry over the handling of the migrant crisis demands that elected officials set the same intention in prioritizing residents who have been waiting to have their needs met comprehensively.

“That’s really at the heart of what equity is,” Honoré said. “When it gets to community, we don’t care where the funds are coming from. We just want to know it’s coming and how it’s being used. And is it being used to really service the community? Is it being used equitably? Aren’t the people who need it the most getting it first?”

At Concord Missionary Baptist Church, Phelps’ congregation cuts through the tension by making sure both community members and migrants get the help they need.

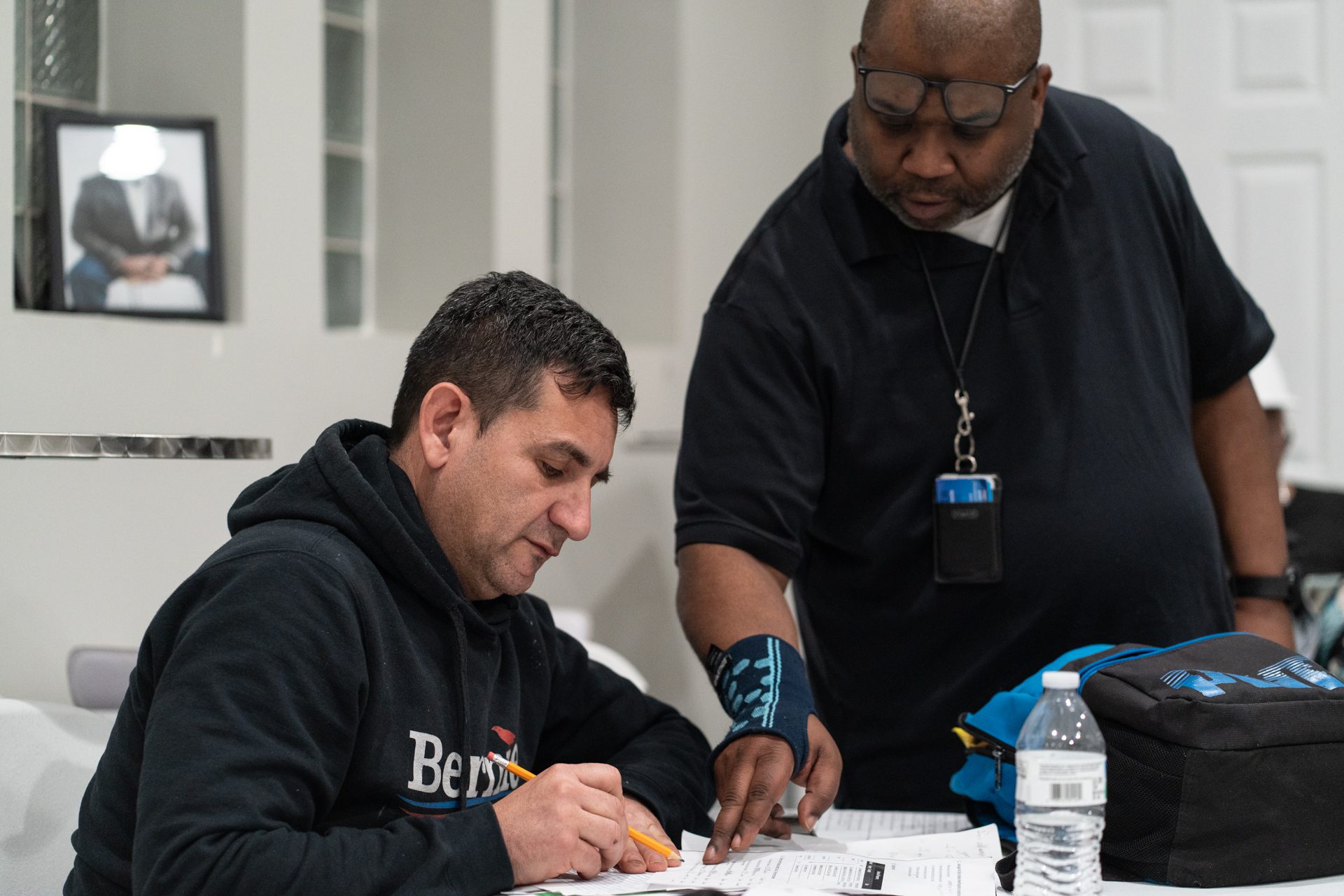

At the church’s Home Away From Home Center, the church listened to the needs of people fleeing from the effects of war, violence, persecution and political disruption and the greater community to offer services that help both cohorts. That includes English as a Second Language classes (ESL), legal counseling, and support finding jobs. On Monday and Wednesday nights, anyone can take ESL classes and earn their GED in partnership with Kennedy-King College. And the church also hosts bilingual worship services in English and Spanish.

“I’ve been pastoring here for 29 years, so I’ve been with the African American community. And here is the deal: I’m still with the African American community,” Phelps said. “We refuse to just take sides because we feel that this is a humanitarian crisis. It’s an opportunity to help not only the migrants but an awesome opportunity to help the Black and Brown communities that were underserved because we’ve shown and demonstrated that we can.”

Correction 4/30/24: An earlier version of this article incorrectly spelled Leslé Honoré name. Her name is spelled Leslé, not Leslie.

This article is part of the Migrant Crisis Reporting Project, made possible by a grant from Healing Illinois, an initiative of the Illinois Department of Human Services and the Field Foundation of Illinois that seeks to advance racial healing through storytelling and community collaborations.

The project is in response to the ongoing migrant crisis, which has seen over 39,000 migrants bused or flown to Chicago since August 2022.

Managed by Public Narrative, this project enlisted two local media outlets to produce impactful news coverage on the disparities and tensions within and among Chicago’s diverse communities while maintaining editorial independence.

Bring power to immigrant voices!

Our work is made possible thanks to donations from people like you. Support high-quality reporting by making a tax-deductible donation today.