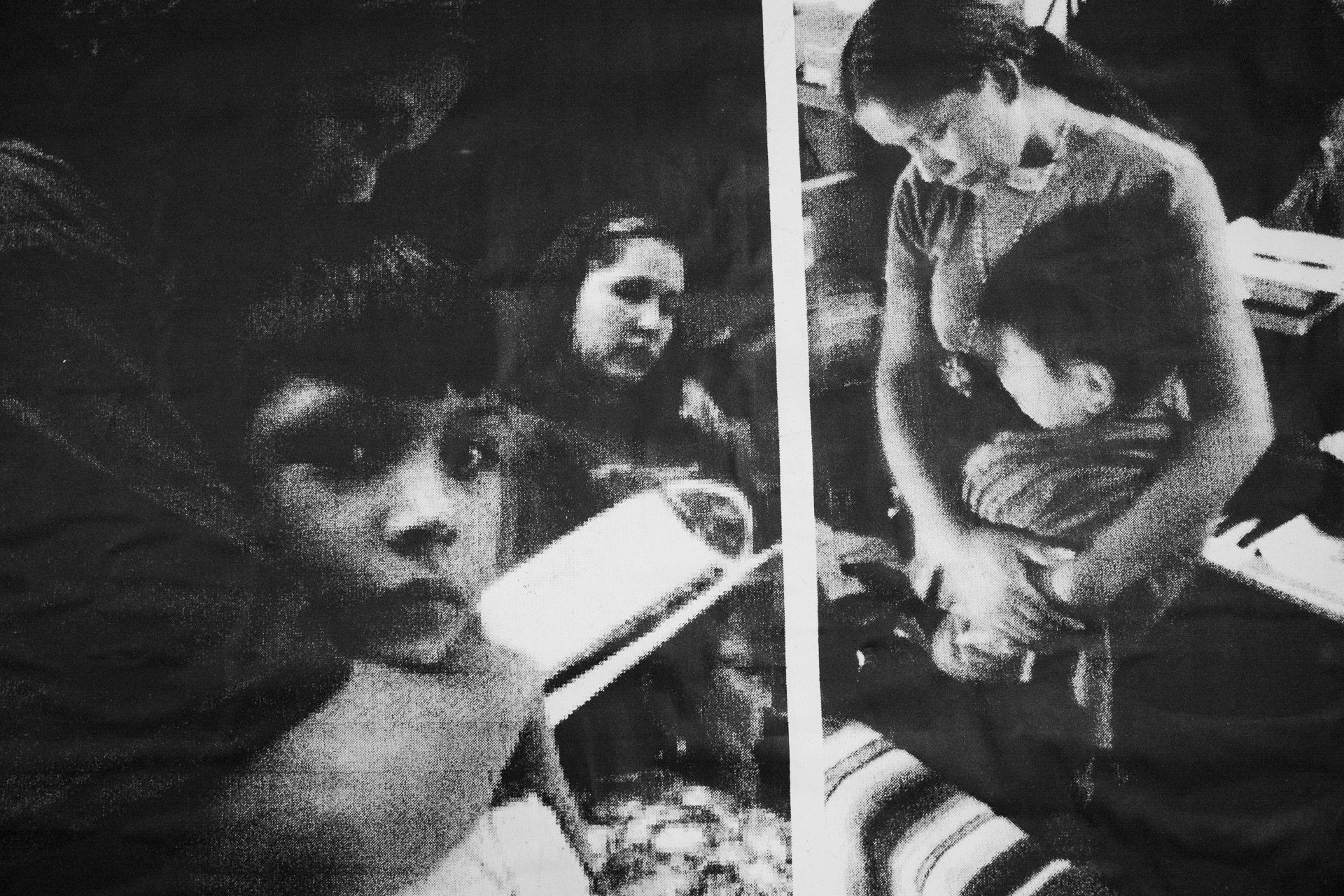

Sebastian Hidalgo for Borderless Magazine

Sebastian Hidalgo for Borderless MagazineElvira Arellano retells the story of when she took a stand to fight for her son and her work to protect undocumented immigrants.

Elvira Arellano describes herself as a mom and a worker. But 20 years ago as she worked cleaning airplanes at O’Hare International Airport, Arellano says that immigration law enforcement saw her only as a potential terrorist. Caught up in the post-9/11 immigration raids, Arellano was separated from her three-year-old son and detained.

A year later, she was granted a stay of deportation through a U.S. immigration court because of her son’s illness. Released from ICE custody, she became inspired by the activism of members of the Adalberto Memorial United Methodist Church in Chicago, who led protests against immigration raids. Wanting to give her son a better life, she began organizing marches with church leaders and community organizers for immigration reform.

Want to receive stories like this in your inbox every week?

Sign up for our free newsletter.

In 2006, Arellano found herself at the center of heated discourse on U.S. immigration policy. Undocumented and facing deportation, she decided to claim sanctuary and take refuge at the church. Her choice set a precedent, prompting churches in other states to also provide sanctuary for undocumented immigrants.

Today, Arellano’s asylum case is still pending. As she fights to remain here, she has continued to help immigrants in the U.S. and in Mexico, from speaking with politicians to organizing supply drives during the pandemic.

Borderless Magazine spoke with Arellano about her faith, her decision to take sanctuary and what 15 years of uncertainty has meant to her.

After 9/11, the federal government executed raids of the homes and workplaces of immigrants to find potential terrorists. They then went to airports. I was arrested on December 10, 2002, on charges related to using a fake Social Security card in a federal workplace. ICE came to my house and knocked on my door, asking me if I carried weapons. I told them to not enter. I am not a terrorist. I was a worker, a mom — the only thing that I did was work to survive in this country with my son. I was then detained. But my three-year-old son couldn’t come with me.

While ICE was processing me, I saw more people detained. I saw a friend from work. He was from Guatemala and so was his wife. I knew their child. In my head — like them — I was already making big plans for my son and I. With the little that I had saved in my bank account, I told myself that if I was deported, I would buy a plane ticket to Mexico and live with my son. But when I was arrested, my world was closing in because I wasn’t sure if I would survive in Mexico. Where would I work, especially having my young son?

I was released a few days after and immigrant officials assigned me to a federal lawyer. Organizers started calling me to go to protests. I met the Illinois Coalition of Immigrant and Refugee Rights and members of the Adalberto church, including my pastor Emma Lozano. Their organization was called Centro Sin Fronteras; all of them were Puerto Rican. They held a press conference at O’Hare protesting my arrest. The media learned about my case, and I remember telling the press that I was a mother who wanted my son to succeed in life.

Read More of Our Coverage

Church members later invited me to attend their Sunday mass. It gave me joy to see how they celebrated during the service and the way they spoke about the importance of the family and the lucha. There was always an agenda for the next week on protests or rallies to defend immigrant families and workers against deportation. I started to come to the church more often, and it led me to being a member of the church for more than 15 years. I would later start organizing marches with others who shared a similar struggle.

In 2006, I remember telling one of my pastors that I wanted to take sanctuary at the church. I wanted to fight more for my rights, and I did not want to be deported. We didn’t know what would happen. That year, I was sentenced to three years of probation, and I had to present myself to an immigration court to be deported. At any moment, immigration [authorities] could arrive and arrest me.

The Puerto Rican community was one of the most important communities that helped me during that time. All of them, including young people, came to the church to protect me. There was one person always outside guarding the church entry. The most impactful moment for me was when that person held up the Puerto Rican flag as a symbol of resistance and the lucha.

My faith grew each day. After one year of staying in the church, I decided to leave. I told myself that it’s time to fight for justice outside of Chicago. I went to California, where three churches had declared themselves publicly as sanctuary churches for undocumented immigrants. I went to visit immigrants who were staying at Los Angeles’s Our Lady Queen of Angels church. It was around 1 p.m. when immigration officials arrested me. And at 10 p.m. I was deported back to Tijuana.

In Mexico, job recruiters wouldn’t accept me for any jobs because they said I was Elvira Arellano, the activist. They would say, “No, we don’t want her here because she’s going to assemble workers to join her protests.” I was fired because of my activism. I was no longer eligible to work. I didn’t finish high school in Mexico and didn’t have a document that said I had the skills to work at these jobs. So I decided to return, and I graduated.

In Mexico, I would always go to protests. I was fighting for the rights of Central American immigrants and migrants. I would go with others to the U.S. embassy to call for immigration reform in Arizona. When SB-1070 passed, we were there to demonstrate.

After over seven years, I decided to come back to the U.S. I crossed the border. I didn’t think I would be able to come to the U.S., but here I am. I am supporting my son so that he can have a good education. He is almost finished with college. When I was at his high school graduation, I cried because I never thought he was going to be graduating in the U.S.

My stance hasn’t changed on bringing justice for undocumented families. Here in the United States, unfortunately, we undocumented immigrants have become just another political tool. Republicans use us to cause fear among their supporters by saying, “Look! They are invading our country!”

We are tired of hearing so many lies about us. Our lives shouldn’t be talked about like game matches. This is a humanistic issue.

Last year, my court date was canceled due to the pandemic. There is no upcoming date for now. It’s possible that I will lose. It’s also possible that the judge has discretion over my case and he might let me stay in the U.S. If they deport me, I would be deported for up to 20 years.

Right now, I have the privilege to have my work permit and was able to receive a stimulus check. But a lot of families were not able to receive the stimulus check because they didn’t have a social security card.

We have to keep fighting for all undocumented immigrants. I leave work for many weeks to participate in rallies and protests in Washington and other places, to gather in front of congressional and Senate offices so they can fight for us. There is a possibility to give legal statuses to 7 million undocumented immigrants. Imagine the day we are able to freely travel and see our families. That would be a dream come true.

Bring power to immigrant voices!

Our work is made possible thanks to donations from people like you. Support high-quality reporting by making a tax-deductible donation today.