Photo by Samantha Cabrera Friend for Borderless Magazine

Photo by Samantha Cabrera Friend for Borderless MagazineThe developer who ordered the eviction will demolish the Little Village building that housed the community space La Casa del Inmigrante.

On the last night in their home of five years, Marcos Hernandez and Ivan Cruz were restless.

The musicians had emptied out all the rooms, ordered a pizza and reminisced on their time in a home they had also built as a community space using their own funds. They also created a banner they would hang from the roof as a final goodbye message: “El dinero no puede comprar la dignidad”: “Money can’t buy dignity.”

News that puts power under the spotlight and communities at the center.

Sign up for our free newsletter and get updates twice a week.

Those familiar with this space for music, arts and community support, at 3200 S. Kedzie in Little Village, called it La Casa del Inmigrante, or the Home of the Immigrant. Its residents often hosted punk shows, sometimes as fundraisers to support causes in Mexico, from earthquake relief efforts to the operations of an anarchist library. When newcomers — usually immigrants from Mexico — needed a place to stay, they could find a home there.

On Thursday, September 9, that era of La Casa ended when its residents were forced to leave under a court-ordered eviction. Hernandez, Cruz and three other artists living in the space have fought the eviction over the past year in a case that unfolded during the COVID-19 pandemic and a state-wide eviction moratorium. The building’s owner, Chicago Southwest Development Corporation, plans to demolish the building and use the cleared land for the 32-acre Focal Point Community Campus. The campus would be home to a new St. Anthony hospital facility, mixed-use retail and possible residences.

CSDC, whose CEO Guy Medaglia also heads St. Anthony Hospital, said the property was never zoned for residential use. But because the developer was unable to serve a copy of the summons and complaint to the residents, it was unable to evict them for several months.

“They are violating the law by not only trespassing but by converting part of the building into a residential dwelling unit,” said Lenny Asaro, an attorney representing the CSDC, in February. “They never had a right to occupy the building.”

In a July 23 hearing, the group’s lawyers argued that because the moratorium is intended to prevent homelessness or congestion from people moving into others’ homes during a global pandemic, that it would apply in this case as well.

Marcos Hernandez narrates the message of a banner that he and fellow residents of 3200 S. Kedzie left the morning of their eviction on Sept. 9, 2021 in Chicago, Ill. The banner states, “In this house, lessons were given on solidarity, mutual support, art, music and justice, but the most beautiful lesson we gave to St. Anthony hospital, Chicago Southwest Development Corporation. They learned that money can’t buy dignity. Video courtesy of Marcos Hernandez

“Clearly, that concern is just as relevant in the question of the displacement of the groups,” Sally Robinson, one of the attorneys for the residents, said.

CSDC lawyers argued they were trespassing and therefore not protected under the moratorium.

While pushing for the right to stay under the eviction moratorium, the artists have encountered harassment from security and police. Last October, CSDC hired American Demolition to erect fences around the building, which prevented the residents from accessing their cars.

Read More of Our Coverage

“We had to deal with the city, with Saint Anthony, with American Demolition,” Cruz said. “At the time they even came and started doing some demo in the front and the back. We told them, ‘Why are you doing demo? You’re putting our lives at risk.’”

“We knew we weren’t up against a normal landlord,” Hernandez added. “We were up against a private company that had their guard dogs and henchmen at their side.”

CSDC did not respond to multiple requests for comment on the eviction and the details of the case.

Kelli Dudley, a lawyer representing the residents, described a situation that her clients believe was an unusual eviction tactic. In August, someone changed the number on the building from 3200 to 3210 in order to match the judge’s order to evict residents of 3210. Security camera footage reviewed by Borderless Magazine shows when someone, who the musicians say is from CSDC, changed the numbers on the door. The judge ruled that their unit was part of the property covered by the eviction order.

“We would’ve looked crazy if we sat around and said, ‘What will we do if they threaten to put our lawyer in jail, what if they change the number the day before eviction?’” Dudley said. “Well that has never happened before, but it happened.”

In December 2020, CSDC asked the city to inspect the building, filing a request through the Drug and Gang House Enforcement unit. Dudley questioned whether this is a sign of how more vulnerable people are treated during the eviction process. She decided to inquire about whether the musicians were being unfairly targeted, and in her inquiry mentioned that the city could face a potential lawsuit if the inspection proceeded.

“There was no reason for those five individuals to be considered drug and gang,” Dudley said. “I raised the question to the city, ‘Hey if I move in five old white ladies with rescue dogs and yoga mats, are you still going to call us drug and gang?’”

Dudley asked the city whether CSDC’s request for this inspection violated the Fair Housing Act, which prohibits discrimination in housing because of race, color, national origin, religion, sex, familial status and disability.

As a result of this inquiry, Dudley said, the city held off on the inspection.

As the residents reflected on the eviction process, they described feeling aggression from the developer.

“I don’t know why they treated us so unjustly. Maybe because we’re immigrants, maybe because we don’t speak perfect English,” Hernandez said in Spanish. “Before anything else we are human beings, with or without papers. But sometimes I wonder if they would’ve treated a white person or a citizen differently.”

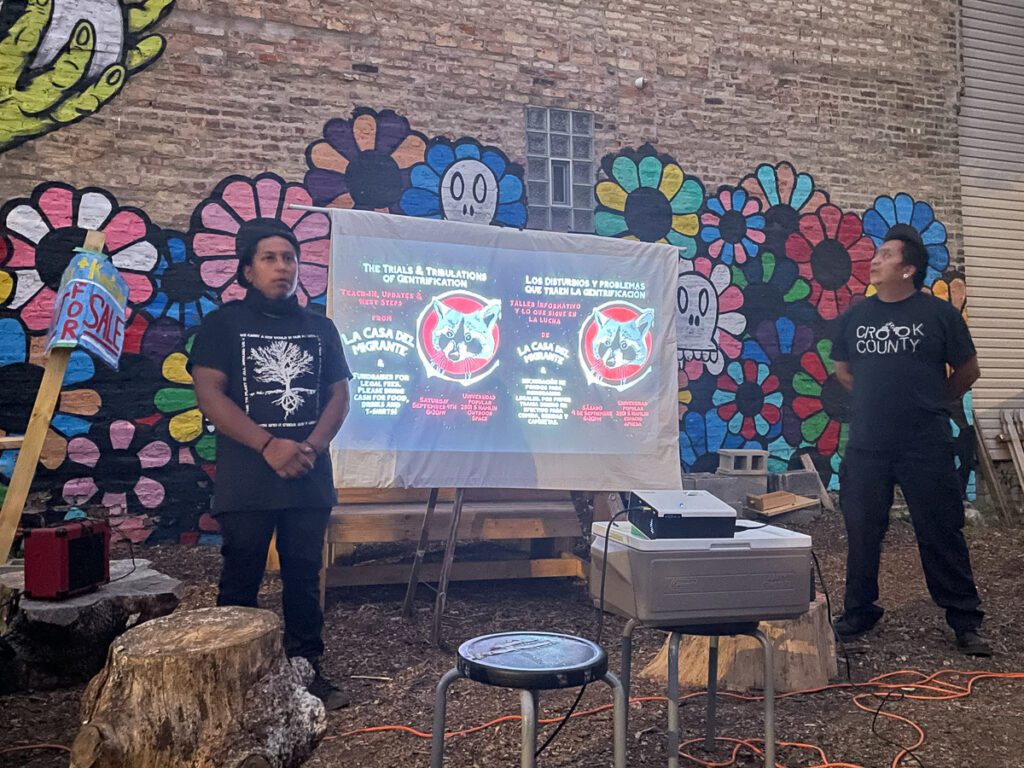

Last Saturday, ahead of the eviction, community members gathered at Universidad Popular community center for a fundraiser to cover some of the legal fees. In attendance was neighborhood organizer Lucky Camargo, who has been outspoken about the residents’ rights and the need for more community-oriented development in Little Village.

“They are already planning how this neighborhood will change. It’s beautiful, who doesn’t want that?” Camargo said in Spanish as she presented the architectural plans for the Focal Point campus. “But what we’ve seen with these types of projects is that lower-income people get pushed out.”

While they’ve been forced out and now live separately, the five remaining residents of Casa del Inmigrante are already seeking a new shared space to continue their community work. Hernandez said they’ve already made a promise to a community in Puebla, Mexico for 200 shoe donations, and they plan to find new ways to keep those activities alive.

“Having been in this place was beautiful,” Hernandez said. “It was chingon to create this place with our own hands, our own money, and to do what our heart told us with our ideals. They think we lost something, but we didn’t lose.”