Photo courtesy of Alyssa Schukar

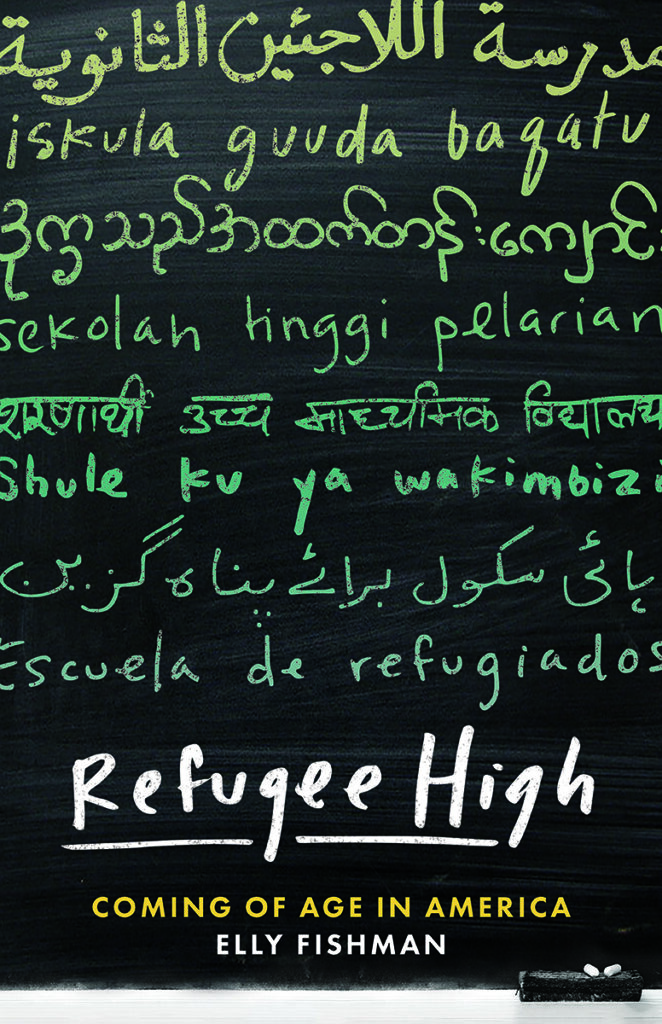

Photo courtesy of Alyssa SchukarWriter Elly Fishman spent a year chronicling the lives of young refugees and immigrants at a Chicago public school in Rogers Park for her new book, Refugee High: Coming of Age in America.

For a century, Chicago’s Roger C. Sullivan High School has been a home to immigrant and refugee students. In 2017, during the worst global refugee crisis in history, its immigrant population numbered close to 300 — or nearly half the school — and many were refugees new to the country. These young people came from 35 different countries, speaking among themselves more than 38 different languages.

For these refugee and immigrant teens, life in Chicago is hardly easy. They have experienced the world at its worst and carry the trauma of the horrific violence they fled. In America, they face poverty, racism and xenophobia, but they are still teenagers—flirting, dreaming and working as they navigate their new life in America.

Writer Elly Fishman chronicles the lives of a few of these young refugees and immigrants at Sullivan High School in her new book, “Refugee High: Coming of Age in America.” Fishman spent time with the students during the 2017 school year, not long after President Donald Trump had enacted his first travel ban limiting the number of refugees and immigrants allowed into the United States from predominantly Muslim countries.

In the following excerpt, Fishman tells the story of Alejandro, who is waiting to hear whether he will be deported just days before he is scheduled to graduate.

Alejandro has been on edge for months. Slumped in his seat in the fifth row of the school auditorium, the senior, who hasn’t removed his backpack, pulls out his phone. He’s not particularly interested in the winter holiday concert, or what Sarah calls “mandatory fun.” On stage, a Rwandan boy beats on the drums while a Syrian sophomore accompanies him on flute as a group of singers belt out Tom Petty’s “Free Falling.” Students across the auditorium film the show with their phones while staff, most of whom lean against the southern wall, sway slightly in place. Next up, a second group sings “Feliz Navidad.” Alejandro looks up; he knows this one. The program continues with “Jingle Bell Rock” and “Auld Lang Syne.” When Lauren steps up to the microphone, the room cheers. She may feel apart from her peers, but she is not without fans. The rest of the Sullivan rock band shuffle in behind her. Hardly a beat passes before the first notes of No Doubt’s “Just a Girl” sizzle across the space. The senior singer is backed by the Burmese bassist and together their swells of sounds bring dozens of students to their feet. With each verse, Lauren seems to lean deeper into Gwen Stefani’s righteous anger. It’s a sharp contrast to her general soft demeanor, but the edge suits her. By the time she reaches the first chorus, she crescendos into a full belt. A handful of students shout-sing along with her. Alejandro, however, isn’t so moved. He’s back on his phone, absorbed by a FIFA highlight reel.

It’s hard for the eighteen-year-old to lose himself in a school concert while he lives in limbo and waits to make his final appeal for asylum. Unlike refugees, who arrive in the United States with protected status and who are given green cards and a path to American citizenship after five years in the country, those like Alejandro, who seek asylum after reaching the U.S. border, must plead their case to an immigration judge. The judge, in turn, decides whether to grant the individual asylum or deport them back to their home country. For the last five years Alejandro’s immigration status has been litigated repeatedly and there’s another hearing at the end of the school year. The new Trump administration policies, which include increasing the number of ICE officers, prioritizing prosecution of immigrant offenses, and limiting privacy for unauthorized immigrants seeking status, put Alejandro on tenuous ground and anything he’s involved in just might work against him.

In 2013, Alejandro arrived in Chicago to meet his father, who too had come to the United States a decade earlier. Though he had put twenty-eight hundred miles between those who hunted him in Guatemala City and himself, Alejandro has never felt totally at ease. Not only were the killings and other violent memories impossible to shake, gangs seemed to be everywhere in Chicago, too. When he started as a freshman at Mather High School, a modernist white brick building that housed more than 1,650 students, Alejandro felt invisible. He liked that. But when he came upon a group of boys smoking a joint in the bathroom, Alejandro was awakened to a world inside Mather. He started to see drugs all over the school. He noticed gang symbols on lockers and coded handshakes between boys in the hall. Though the gangs were new, he recognized the modes of communication. After just a few weeks at Mather, Alejandro told his father he wanted to transfer to another school.

At Sullivan, Alejandro landed in Sarah Quintenz’s English class. At first, he disliked Sarah. Her acerbic style doesn’t work for everyone. She pushed her students by repeatedly asking them: Are you dumb or are you learning English? A refrain that Sarah first used when pointing to a poster of her toddler son. She said: “You are not dumb. He’s dumb and he’s learning English.” And added, “You all know how to wipe your own butts, I hope.”

Her point was that no one should mistake the student for slow because they didn’t speak English. But while students’ English proficiency was not a measure of their intelligence, they still had to speak the language in Chicago to be taken seriously. The expression became a classroom catchphrase. But Alejandro didn’t buy it. He found Sarah’s haranguing humiliating. She got under his skin. And one day Alejandro, who had managed to temper his anger, burst wide open.

Midway through class Alejandro made a snide remark under his breath. “Knock it off, Alejandro,” Sarah said from the front of the classroom. “Shut the fuck up,” Alejandro responded in Spanish.

Sarah turned away, prepared to let the comment slide. But then another student spoke up.

“Don’t talk to her like that,” the student responded to Alejandro in Spanish. “You shut the fuck up.”

“Don’t tell me what to do,” Alejandro said, now more heated.

“She’s the coolest teacher we have. Seriously, don’t talk to her like that.”

Both boys stood up from their chairs. Alejandro threw a punch. He was knocked down by a retaliatory blow. There was blood on the floor. Sarah yelled for Sullivan security guards, who ran from the front desk to her room within seconds.

A few days later, Sarah met with Alejandro’s father. She told him his son was both acting out and clashing with others. Sergio explained that ever since Alejandro had arrived in the United States he’d been angry about everything. He was angry about leaving his mother and his friends. He was angry at his father, who had become a relative stranger in their years apart from one another. Sarah implored Sergio to spend more time with his son.

Read more

The fight was a turning point for Alejandro and Sarah. When Alejandro learned that Sarah hadn’t told his father about the fight, he thanked her. After that, he started spending his lunch periods in Sarah’s classroom. By spring, Alejandro ate every day with Sarah. The classroom that broke his patience was now his safe space. He not only ate lunch there, he came to maintain order at other times of the day, too. He helped keep the room neat and Sarah’s work manageable. She joked to him that he was her Secret Service detail. If students came to her with questions when Sarah was engaged, Alejandro would intercept them. “Ms. Q. is busy right now,” he’d say, “ask me.”

Alejandro shared details about his new relationship. He chronicled his growing love for salsa and tamales and complained about teachers he’d come to dislike. He never, however, talked about his past. That changed when Sarah assigned Jorge Ramos’s book Dying to Cross. Like many of her teaching units, Sarah hoped the book, which tells the stories of nineteen people who died inside a trailer truck that was meant to carry them from Latin America to Houston, Texas, would connect with students’ own migration stories. The class spent one full month discussing the book and its themes. She had students present on different characters and stories. When the class reached the section in the book that detailed how migrants crossed over the Rio Grande to reach the U.S. border, Alejandro spoke up.

“I did that,” he told Sarah and the class.

“You crossed a river?” Sarah asked, puzzled.

“I crossed that river.”

Sarah pulled up a map on the overhead projector. She pointed to it. “This same river? The Rio Grande? What was that like?”

“Really fucking scary.”

These days, the ELL office remains one of the only places Alejandro finds community. He tried other groups, but nothing stuck. When he first started at Sullivan, he played on the soccer team. Alejandro was a strong player and leader; he was elected team captain his second year on the squad. While everything else was new in America, the rules, pace, and play of the game remained the same as in Guatemala. When the team took to the field, they weren’t thinking about the people they’d left behind. Alejandro didn’t focus on his precarious future. The world shrunk to the size of the field. He found comfort in that. But soccer also brought out his anger and competitive nature. A bad referee call would leave him fuming. And once triggered, Alejandro found it difficult to reel himself back in. So, after his sophomore year, he quit. He also tried going to church with his girlfriend and her family. They went every Sunday and always shared a family meal afterward. But Alejandro was turned off by how women dressed up for church. He thought the short skirts and low-cut tops looked like outfits meant for a dance club. He decided he’d prefer to pray at home. From then on, whenever anyone asked him what his church was, he told them, “My house.”

Last month, as Alejandro prepared to make his second plea for asylum, he asked Sarah to write him a letter of support. In the days leading up to his November 9 court date, he spent almost every period in the library. He’d hole up in a corner and consult a stapled stack of papers. The document, a script of sorts, consisted of the forty questions of the intake questionnaire given to unaccompanied migrant children once they are brought into custody, as well as his answers. The questions, which are modeled after those on the I-589 form, the U.S. application for asylum, are meant to turn difficult, complex lives into well-shaped narratives. For Alejandro, the specifics of his escape from Guatemala were hard to recall. They have faded as he’s built a life in Chicago. But his lawyers told him he had to do his best to memorize his answers. They told him that the judge would try to catch any discrepancies. When Alejandro felt overwhelmed, he’d turn to Sarah who would always carve out time to talk.

Less than forty-eight hours before he was due in court on November 9, Alejandro received a phone call. It was his father, Sergio. He explained that the lawyers had called and told him that Alejandro’s court date was being pushed back. The court was behind on its cases and it didn’t have time to hear Alejandro’s. He’d have to wait to receive a new date. When he did, the email read June 11, two days before he was due to graduate from Sullivan.

Elly Fishman will be speaking about her new book, Refugee High: Coming of Age in America, at a virtual event hosted by the American Writers Museum on Tues. August 10 at 6:30 pm. Find details and register for the free event here.