April Alonso for Borderless Magazine/ CatchLight Local Chicago

April Alonso for Borderless Magazine/ CatchLight Local Chicago In the midst of a housing crisis that has left immigrant renters among the most vulnerable, a group of immigrant punk rock musicians are fighting to stay at a commercial building they’ve called home for years.

The squat two-story, yellow brick building at 3200 S. Kedzie in Chicago’s Little Village neighborhood wasn’t always so quiet. In past years, the colorful space inside had been known to boom with the sounds of live punk music, cheering audiences, and heavy metal.

A crew of Latinx immigrant musicians had built a thriving community arts hub out of the former office space, which was tucked next to a metal recycling company. They called it La Casa del Inmigrante: the Home of the Immigrant.

News that puts power under the spotlight and communities at the center.

Sign up for our free newsletter and get updates twice a week.

Here, people from the neighborhood could collaborate with other artists and learn about making music, DJing, theater and graffiti art. Local and out-of-state bands, like immigrant hardcore punk band Lakras from New York City, would also come through to play. Events would often double as fundraisers for communities in need: In 2017, the group sent money to Oaxaca, Mexico for families who were displaced by an earthquake.

While a community arts space at heart, La Casa del Inmigrante has also served as a residence for an ever-changing roster of immigrants for the last five years. Juan Herrera, a graffiti artist and one of the residents, said there have been around eight people who have made their homes there, and a larger network of people who have used the space as an art studio.

“We fixed up everything to be able to have a kitchen, bathroom and shower,” Herrera said in Spanish.

“I paid out of my own funds to create this space,” resident Marcos Hernandez, who also plays drums in the local punk band Desafio, said in Spanish. “Little by little, people in the city started to join.”

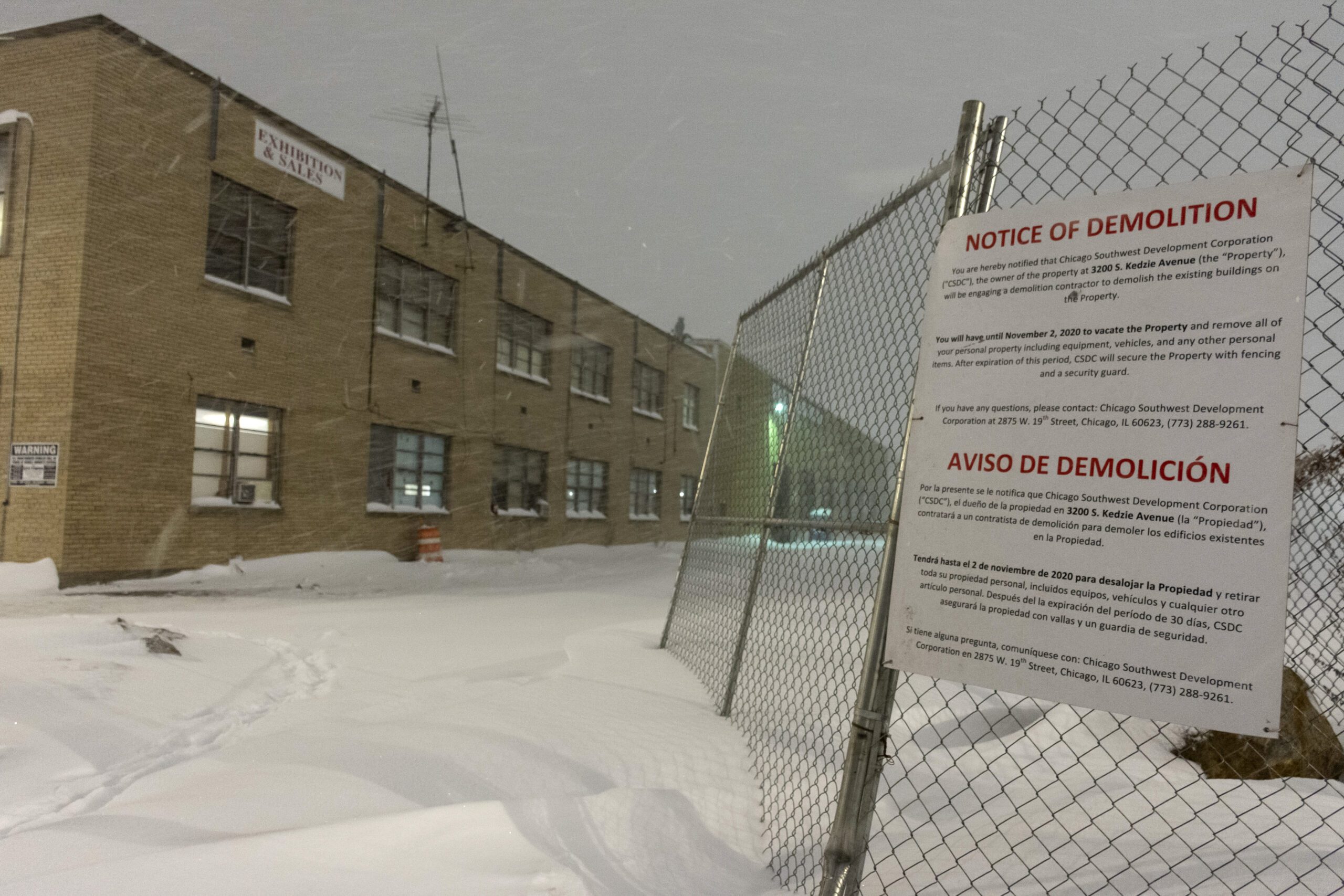

But this community has now come under legal scrutiny, and its members face eviction. The building’s owner, the nonprofit Chicago Southwest Development Corporation, is seeking to demolish 3200 S. Kedzie and neighboring structures, which it calls unsafe.

The CSDC plans to use the cleared land to develop the 32-acre Focal Point Community Campus, described on the project’s website as a “bold and visionary idea to provide Chicago’s vibrant west and southwest side communities greater opportunity to thrive and sustainable change, while celebrating the diversity and rich history of its neighborhoods.” The campus would be home to a new St. Anthony hospital facility, mixed-use retail and possible residences. CSDC’s CEO Guy Medaglia also heads St. Anthony Hospital.

The property at 3200 S. Kedzie is currently zoned as a commercial, manufacturing and employment district intended to serve as a buffer between manufacturing and residential and commercial areas. The city zoning code does not allow housing in the zone, nor people living in the building.

“They are violating the law by not only trespassing but by converting part of the building into a residential dwelling unit,” said Lenny Asaro, an attorney representing the CSDC, of the Casa del Inmigrante residents. “They never had a right to occupy the building.”

Read More of Our Coverage

An Underground Community Space

Erected in 1974, 3200 S. Kedzie sits on the south end of Little Village not far from the Chicago Sanitary and Ship Canal. The property is next to the site of the former Washburne Trade School, a union-supported education center that was demolished a decade ago, which the CSDC also plans to develop as part of the Focal Point campus.

The 3200 building’s previous owner, Azteca Mall LLC, had intended to transform the property into an incubator space for local merchants. When those plans fell through, the City of Chicago passed an ordinance in 2017 allowing the city to use eminent domain to acquire the 3200 S. Kedzie property as well as neighboring properties as part of a TIF plan for the Little Village Industrial Corridor Redevelopment Project Area with the intention of transferring the properties to the CSDC. Ultimately, however, the city did not use its eminent domain power, and the CSDC purchased the property outright in 2018 for $4.6 million.

The CSDC’s development plans are now on hold as the dispute over the residents’ rights to live in the property makes its way through Cook County court. CSDC filed an eviction complaint against Juan Herrera and Marcos Hernandez on February 10.

The Casa del Inmigrante residents argue that they have a right to remain in the building at least as long as the state’s residential eviction moratorium is in place. With Gov. J.B. Pritzker’s latest extension of the moratorium, evictions in Illinois are suspended until March 6. The governor has filed new orders every 30 days since the COVID-19 pandemic began, and it is likely that the moratorium will be extended again.

Many of the Casa del Inmigrante residents worked in the music industry before the pandemic and have since lost their jobs and their regular housing. Juan Gonzales was regularly DJing at venues and parties in Chicago before the city shut down due to COVID-19. He has since taken up odd jobs to make up for his lost income but said he has a hard time finding stable work.

“Little jobs here and there, cash jobs,” Gonzales said.

Latinxs have been amongst the hardest hit by the pandemic. In Chicago, Latinxs account for 35 percent of COVID-19 cases despite making up just 28 percent of the population.

“It’s completely illegal,” Marcos Hernandez said of CSDC’s attempts to evict him and other residents. Hernandez noted that CSDC has not yet obtained a demolition permit. Asaro counters that the CSDC cannot obtain a demolition permit until the property is vacated.

“Where are we going to go?” asks Hernandez. “They took away a form of our work, that’s where we made our living. Why are they coming to a poor neighborhood to build this?”

The community at La Casa del Inmigrante began five years ago with Guillermo Hernandez, a theater producer. A lease provided by CSDC shows Guillermo Hernandez as signing a three-month industrial building lease in January 2016, which converted to a month-to-month lease thereafter. The lease notes that “the premises are to be occupied and used solely for the purpose of storage of theater equipment and for no other purpose whatsoever.”

While the lease did allow Guillermo Hernandez to sublease the space with the landlord’s written approval, CSDC’s Asaro states that neither the CSDC nor the prior owner gave such an approval.

When Guillermo Hernandez became sick with cancer, the Casa del Inmigrante community came to his aid. Last January, they raised funds for his medical costs through a show featuring bands such as Maldixion de Malinche, Chango Pardo and Marcos Hernandez’s own band, Desafio.

When Guillermo became too sick to pay rent, Marcos Hernandez sent the Chicago Southwest Development Corporation a check for $3,000 on May 1 to cover the cost of rent. (Monthly rent under Guillermo’s original contract was $1,000). While a representative from CSDC acknowledged receiving the check, the money was never deposited. Marcos Hernandez was told via text message that CSDC would communicate only with “the official lease holder.”

Guillermo passed away in August 2020, and Marcos gave the rejected rent money to Guillermo’s family to help cover his funeral expenses.

In October, the CSDC posted notices of demolition on the building giving residents and tenants until November 2 to vacate the property. CSDC hired American Demolition to erect a fence around the building, and the demolition company hired a security guard to monitor the building.

Marcos Hernandez says that one of the security guards harassed him and other people living at the property. Two videos recorded by Marcos Hernandez on January 13, 2020 obtained by Borderless Magazine* shows an instance in which a female security guard confronts him and appears to taunt him.

“You’re homeless with no money, you have no money,” the guard says in the footage. “It’s cold in there, so how do you sleep?” She then calls the police, saying, “He’s standing here by my car, I will shoot him if he don’t [sic] get from my car.”

“The security guard should not have said that,” Asaro said after Borderless Magazine shared the videos with him. “We do not condone anybody disrespecting anybody.”

Asaro said that CSDC has alerted the demolition contractor of the videos, which in turn addressed the security company. The security guard has since been removed from the site and replaced.

Both Illinois and Chicago law prohibits “illegal lockouts,” when landlords turn off utilities like gas and electricity, block entrances and change the building’s locks before residential eviction proceedings are completed. In the case of 3200 S. Kedzie, Asaro estimates that the eviction process will take three to four months, slowing down the development process and costing the nonprofit money in utility payments, insurance and security.

Tenants or Squatters?

For Metropolitan Tenants Organization attorney Philip DeVon, the Casa del Inmigrante case is not black and white, but it illustrates a clear power dynamic.

“The developer who is well-heeled and funded with spokespeople has all the power,” DeVon said. “It’s evident when you can erect a fence around people while they sleep at night you have the power in the relationship.”

“It’s scary, but the tenants do have rights — they can’t just be locked out,” he added. “And that would be decided in court.”

Ald. Michael Rodriguez (22nd), who oversees the ward where 3200 S. Kedzie sits, has been following the situation and hesitated to refer to the residents as “tenants” or “squatters,” instead calling them “tenants/squatters.”

“I would say there are emergency situations and that a court has to determine if it’s an emergency situation,” Rodriguez said. “The best way through this is an arrangement between the impacted groups.”

Rodriguez noted that throughout the ward last year, his office has fielded a potential record number of requests for help stopping illegal lockouts or utility shut-offs. Despite the COVID-19 residential eviction moratorium in Illinois, tenants across the city have continued to face harassment, with some being forced out by their landlords.

In an immigrant neighborhood like Little Village, undocumented immigrants are some of the most vulnerable. For some immigrants, fear of deportation and language barriers can be an extra barrier to enforcing their rights in these situations as well as added restrictions on accessing employment and aid. Undocumented residents, for example, are unable to access subsidized public housing unless one of the family members they live with has U.S. citizenship or a qualifiying noncitizen status. For these reasons, it’s “very common” for undocumented immigrants to live in units without a formal lease, said Lucky Camargo, a neighborhood organizer.

Calls for Community Input

As the standoff between the development corporation and La Casa del Inmigrante intensifies, the building’s residents have leaned on community organizers, some of whom have been scrutinizing St. Anthony’s $600 million development plan for years. Many see the issue as part of a broader trend of displacement. In a neighborhood where about a third of residents live below poverty level, development plans such as this or those for the Little Village Discount Mall deepen those worries.

Organizer Camargo has been vocal about her opposition to the hospital’s expansion, in the past going door to door to inform residents and organize concerned community members.

After a botched demolition of a smokestack at the nearby Hilco site last year, Camargo said she was surprised to see a demolition sign appear on the building at 3200 S. Kedzie. Once again, she felt that developers had skipped over a community engagement process.

“You have this, you have the discount mall and Hilco, big changes that are happening in the neighborhood, and people are deciding how these neighborhoods are shaped and not including the people who live here,” Camargo said. “So concerns about gentrification are there.”

Rosa Esquivel, a housing advocate with Pilsen Alliance, said that rising rents and displacement that have transformed Pilsen are also starting to affect Little Village. She used to be neighbors with Marcos Hernandez in Pilsen. “I’ve known [the musicians] for a long time,” she said.

“We are not going to take the harassment,” she added. “We should not be harassing human beings in the middle of a pandemic.”

Willie “J.R.” Fleming, an anti-eviction community organizer, said that he’s seen the way evictions in Little Village and other parts of the city disproportionately affect immigrants.

“We call it urban and economic cleansing. These are human rights violations,” said Fleming, who serves as the executive director of the Chicago Anti Eviction Campaign. “These communities have been displaced by urban and economic displacement.”

Fleming said that the Chicago Anti Eviction Campaign and other groups have been monitoring the situation at Casa del Inmigrante to show support.

“[We are] watching what we call market activity,” Fleming said. “That’s going to dictate the activity we’ll take, when we pull up with busloads of people.”

For now, the tenants are working with legal representation to prepare for when the sheriff eventually serves them an eviction notice. They say they have no plans to leave.

“What really makes me mad, it’s the way they’re treating us like we’re not human,” graffiti artist Herrera said. “Right now the problem is with them. They call the police on us, telling us to go. It’s not that we want to stay here forever, but right now the situation is we’re in a pandemic. They need to give us time. It’s been a hustle every day.”

*Editor’s Note: Borderless Magazine has chosen not to publish these videos. We believe hate speech should be recognized but not amplified. For questions, please contact us at [email protected]