Image courtesy of DePaul Art Museum

Image courtesy of DePaul Art Museum At the DePaul Art Museum, a major intergenerational art show celebrates the contributions of Latinx artists with ties to Chicago.

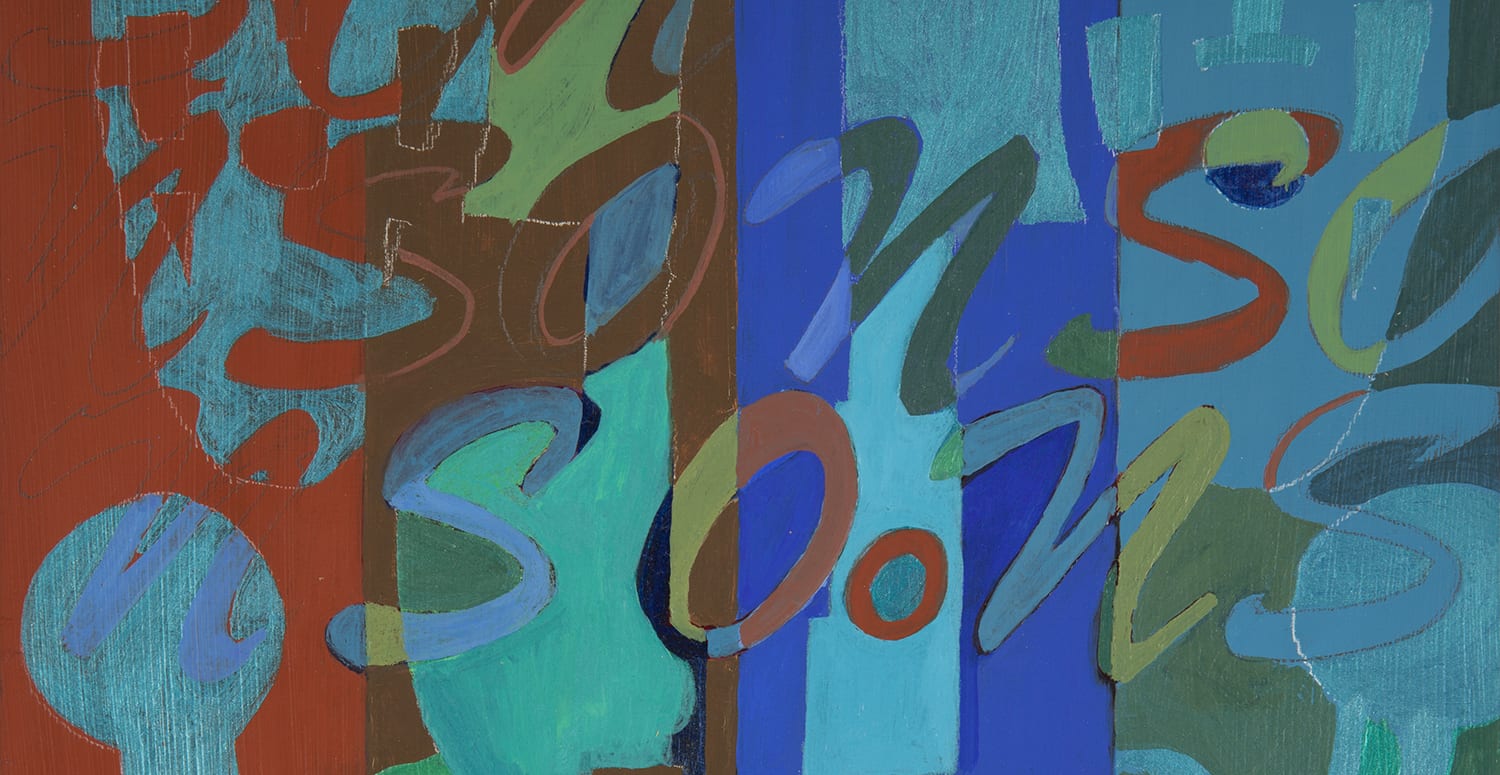

Above: Candida Alvarez’s “Son So & So”

Image courtesy of DePaul Art Museum

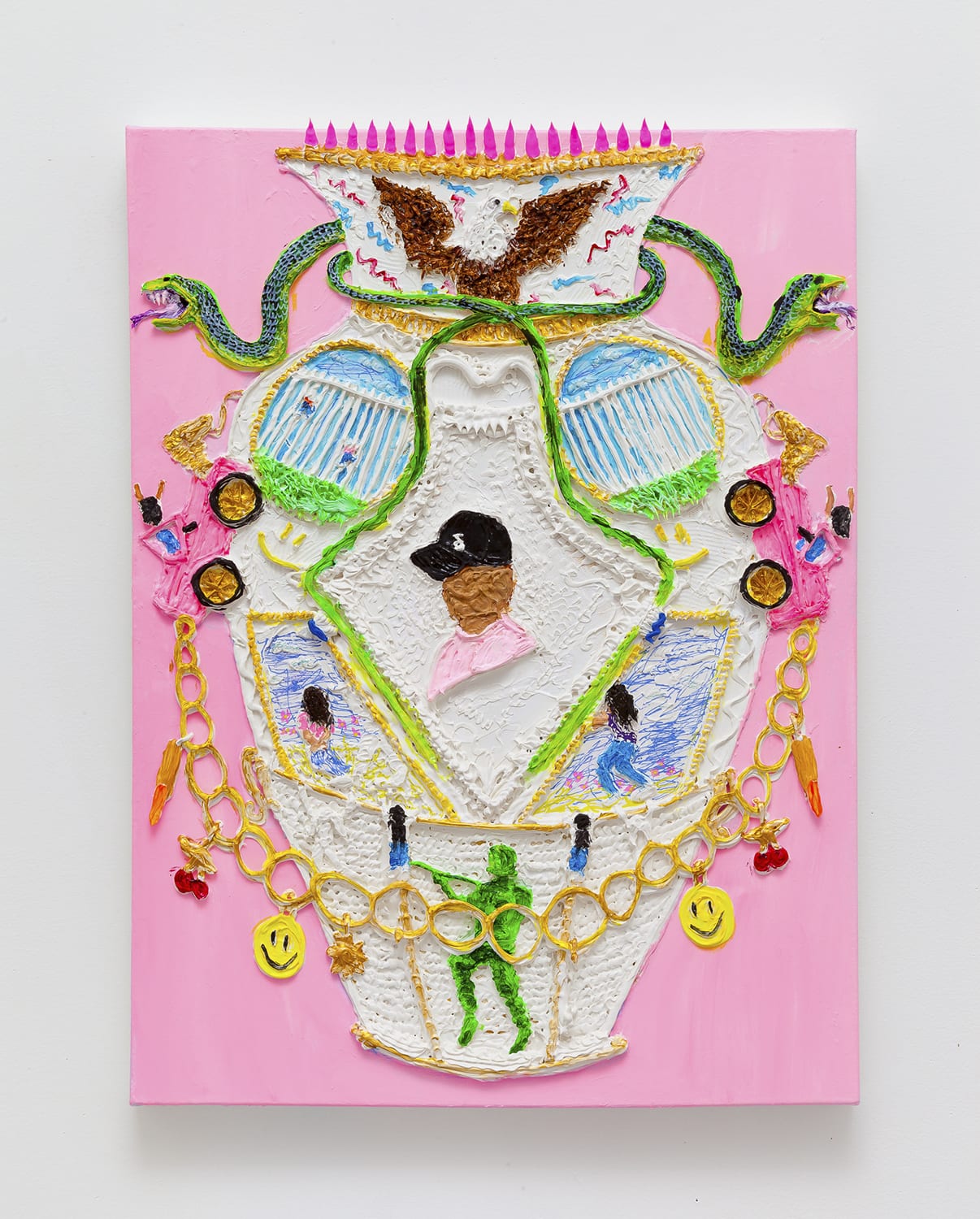

In 2019, Yvette Mayorga began painting vases in her signature technique — piping acrylic colors with cake-decorating tools — to create visceral artworks that challenge the mythos of the American dream.

“A Vase of the Century 1 (After Century Vase c. 1876)” recreates an ornate 19th-century vessel that commemorates America’s centennial, only the Chicago artist has inserted visuals that reflect her personal history as a daughter of Mexican immigrants. A brown-skinned figure in a baseball cap replaces the portrait of George Washington, and vignettes of the United States-Mexico border wall replace patriotic scenes. A youthful charm bracelet, linking smiley faces, cherries, and pink Barbie doll cars, encircles the vase.

For Mayorga, the transformation centers her family’s immigrant experience while anchoring it in histories of oppression and erasure. “My family has contributed to the construction of this country through exploitative labor,” she said. “Retelling these stories and integrating them into historical artworks is a way of making them important. It continues to form our visibility as important figures in the history of this country.”

Yvette Mayorga’s “A Vase of the Century 1 (After Century Vase c. 1876), 2019”

Image courtesy of DePaul Art Museum

Last February, the DePaul Art Museum (DPAM) acquired Mayorga’s painting as part of a major institutional initiative to increase the visibility of Latinx artists, especially those with ties to Chicago. It is currently on view in “LatinXAmerican,” an exhibition of artists of Latin American and Caribbean heritage that showcases a wide range of distinct perspectives on identity, touching on issues such as immigration, cultural diffusion, colonization, labor, and craft.

Contemporary paintings, photography, sculpture and more by nearly 40 artists fill galleries across two floors in what is the largest-ever survey of Latinx art mounted in DPAM’s 36-year history. (DPAM uses the term Latinx as a “nonbinary, gender-inclusive alternative to Latino or Latina” but recognizes that not every artist identifies as such.) Open through August 15, people can walk through the bilingual exhibition virtually while the museum remains closed due to the pandemic.

Most pieces come from DPAM’s permanent collection and were chosen not by a single curator but by six staff and interns, half of whom identify as Latino/a/x. While well-established artists such as Mexican photographer Graciela Iturbide and Chicana graphic artist Ester Hernandez are featured, also present are many artists who have a less robust presence in U.S. museums. These include Salvador Jiménez-Flores, who sculpts stoic, cacti-like totems that symbolize the resilience of immigrants, and Melissa Leandro, whose evocative textile work “fossil things” (2018), which explores cultural identity and domestic space, was acquired by DPAM last year.

Salvador Jiménez-Flores’s “Nopales hibridos: An Imaginary World of Rascuache-Futurism, 2017”

Image courtesy of DePaul Art Museum

“‘LatinXAmerican’ is us exploring cross-cultural connections and the slippery, complicated, beautiful way of living between cultures,”said Laura-Caroline de Lara, DPAM’s interim director. “We’re mining our collection to get a full scope of Latinx artists who are present and really trying to increase our efforts to fill holes, of which there are plenty.”

That latter goal is a core motivation of the Latinx Initiative, DPAM’s multi-year effort to better represent Chicago’s diverse Latinx communities through its collections and programming. Launched last year, the initiative was originally developed under the leadership of former director and chief curator Julie Rodrigues Widholm in response to a 2019 survey on artist diversity in 18 major U.S. museums (DPAM was not among the group). The multi-author study, published on the website of the nonprofit Public Library of Science (PLOS), found that only 2.8 percent of artists in those collections are Hispanic/Latinx. At the same time, looted art and objects from Central and South America, many taken during colonial conquests, remain in collections around the world; thousands of relics continue to circulate on the art market. (A concurrent exhibition at DPAM by artist Claudia Peña Salinas examines disputes over the repatriation of an Aztec headdress currently in a Vienna museum.)

DPAM is still compiling statistics on its 4,000-object collection, but adequate representation of Latinx art is “something we know we’re lacking in,” de Lara said. “And this [initiative] is us actively working on that.” Especially considering that Latinx communities make up 29 percent of Chicago’s population and 16 percent of DePaul’s student body, “it just made sense to curb that disproportionate number,” she added.

“Being part of a university, we also use our artwork as teaching tools. Dealing with themes that reflect our Chicago communities is a big part of what we look for in our work.”

Candida Alvarez’s “Son So & So”

Image courtesy of DePaul Art Museum

DPAM’s “LatinXAmerican” aims to include Latinx artists from different generations and circumstances, reflecting the diversity of the Latinx experience. Pleasant memories are commemorated, as in Candida Alvarez’s energetic 2001 painting “Son So & So,” which is named for both her son and for the rhythms of music from Cuba that she enjoyed while growing up in Puerto Rico. And speaking a language of desire through flower petals, Alejandro Jiménez-Flores delivers tender pastel and plaster works grounded in the artist’s playful childhood experiences in Mexico.

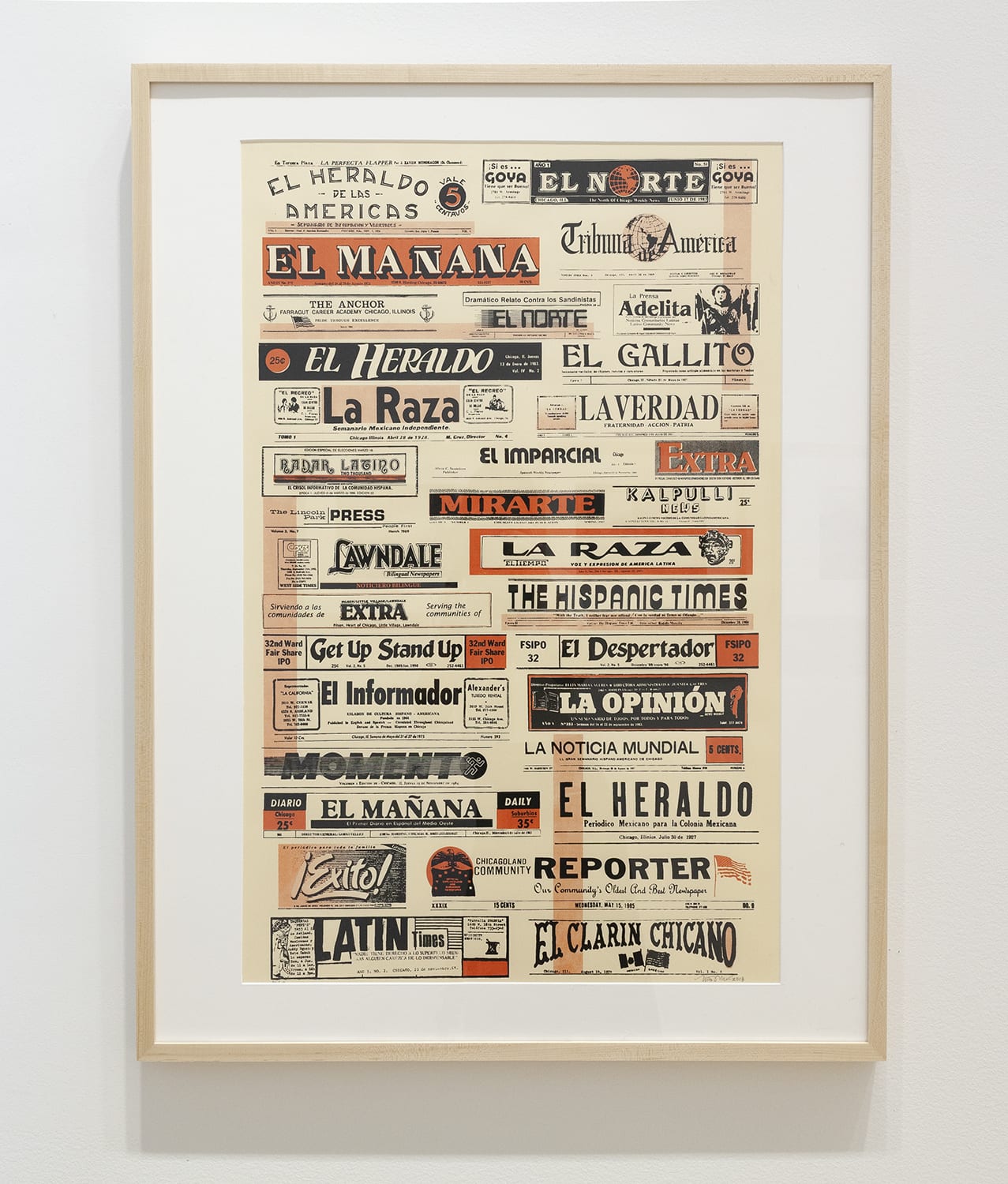

Other works document political organizing and community power, such as Nicole Marroquin’s silkscreen prints, which record Latinx contributions to social justice issues in Chicago. One recounts the details of the 1968 Harrison High School student uprising, when Mexican, Mexican American, and Puerto Rican students walked out in solidarity with Black classmates to protest discrimination. Another compiles mastheads of more than two dozen local Spanish-English newspapers that operated between 1927 and 1985.

Nicole Marroquin’s “Untitled” poster from 2018 depicts the mastheads of Chicago Latinx bilingual Spanish-English newspapers from 1927–1985 that served or reported on Latinx communities of Chicago, and are now out of print and unarchived.

Image courtesy of DePaul Art Museum

The personal and the political meld in Tanya Aguiñiga’s performance work “America’s Wall (El muro de America),” in which she imprinted a section of the U.S.-Mexico border wall on a white sheet. Aguiñiga, a Los Angeles-based artist who grew up in Tijuana, Mexico, made the work as a way to educate people about the border at a time when former President Donald Trump was talking about building a wall.

“People kept asking me, ‘So there’s no wall [already]?’ It was this lack of understanding about the borderlands when they don’t live close enough,” said Aguiñiga, who regularly crossed the border for 14 years to attend school in San Diego. “Not a lot of people [in America] have experiences meeting anybody from the border.”

In 2018, after prototypes for Trump’s wall were built near the California-Mexico border, Aguiñiga and her team traveled there. On the Mexico side, they rubbed a vinegar-soaked sheet on a section of fencing erected in 1994 — strips of corrugated jet landing mats recycled from Operation Desert Storm — effectively rust-dyeing the fabric. “I could then have a fence that could travel,” Aguiñiga said. “I could show it to people and say, look, the fence exists, this is what the texture is like. This fence that traces so many instances of U.S. imperialism and so much pain, specifically against brown people.”

In the performance documentation, the wall prototypes are just visible, their polished surfaces standing in stark contrast to its timeworn predecessor. “The border is literally this massive scar on the land but also through us,” Aguiñiga added. “It’s this constant pain we carry.”

DPAM is just one of many U.S. cultural institutions gradually recognizing these experiences as part of American history. For artist Mayorga, the representation is overdue. “This is the beginning of acknowledging the importance of our voices and to really represent us in contemporary American art history,” she said. “But I hope we continue to be included beyond this frame and not just be defined by our race or ethnicity.”

DePaul Art Museum’s LatinXAmerican exhibit is open through Aug. 15. The exhibition is viewable online while the museum’s facilities are closed due to the COVID-19 pandemic.