Colin Boyle/Block Club Chicago

Colin Boyle/Block Club ChicagoPor qué trabajamos en estas historias, cómo surgió nuestra colaboración con Block Club Chicago y qué aprendimos.

La semana pasada publicamos nuestra serie Después de los autobuses, un proyecto de tres meses de duración en el que los reporteros de Borderless Magazine y Block Club Chicago siguieron a 10 de los más de 3.700 inmigrantes que llegaron a Chicago procedentes de Texas en el marco de la campaña tejana Operation Lone Star.

Esta serie surgió tras meses de entrevistas y conversaciones con los inmigrantes, abogados y organizadores comunitarios. Nuestro objetivo con After the Buses era ayudar a los habitantes de Chicago a comprender mejor la situación y las necesidades de los inmigrantes recién llegados.

Noticias que ponen el poder en el punto de mira y a las comunidades en el centro.

Suscríbase a nuestro boletín gratuito y reciba actualizaciones dos veces por semana.

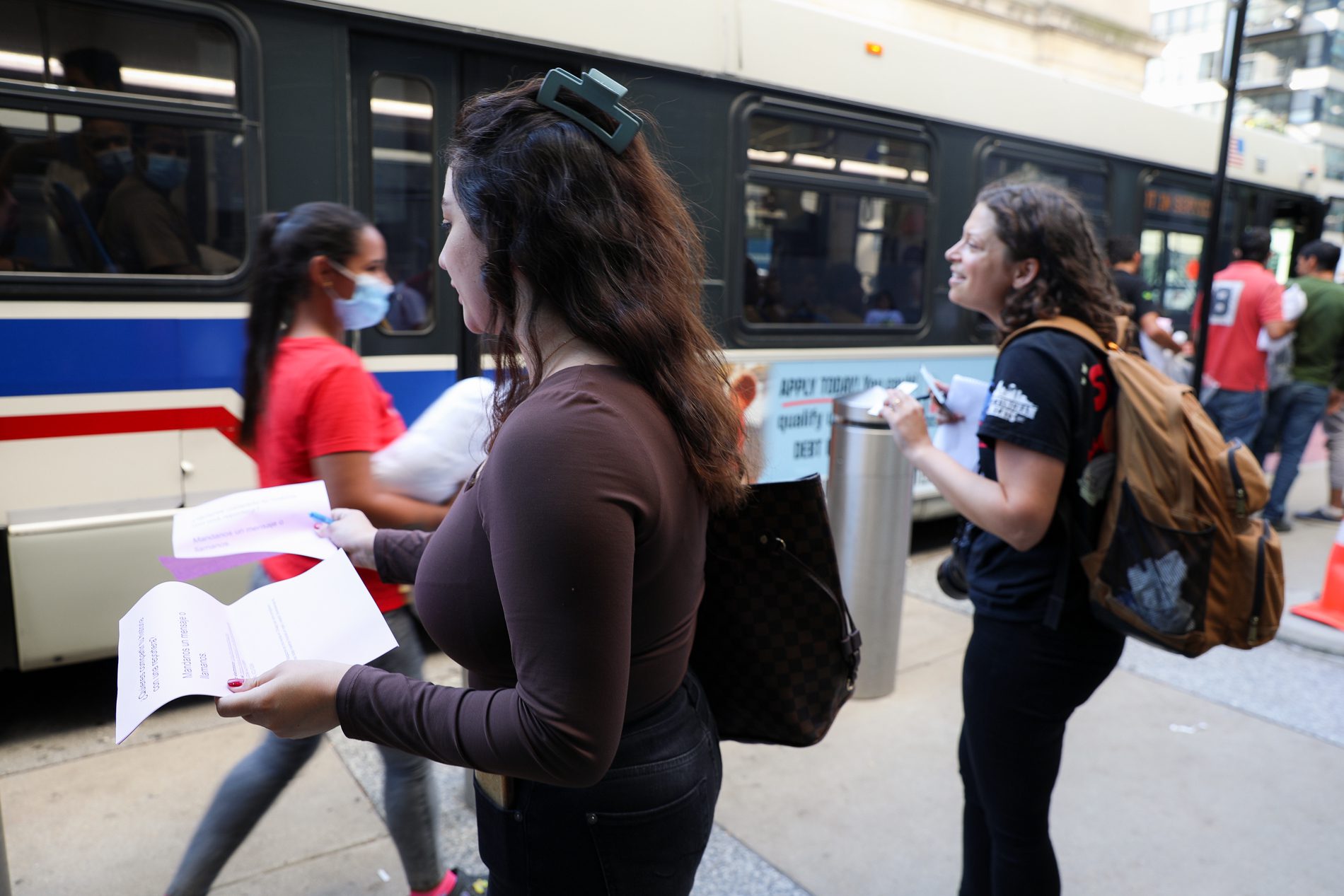

A finales de agosto, el gobernador de Texas, Greg Abbott, empezó a subir a autobuses a personas que habían llegado a la frontera estadounidense y a enviarlas a ciudades lideradas por demócratas en un esfuerzo por presionar al gobierno federal para que promulgara restricciones más estrictas a la inmigración. Desde muy temprano, los periodistas de Borderless acamparon en Union Station, en Chicago, adonde fueron enviadas algunas de esas personas, junto con otros reporteros y organizadores comunitarios.

Tanto Block Club Chicago como Borderless estaban informando sobre esto al mismo tiempo y en el mismo lugar, así que decidimos colaborar e informar sobre historias más contextuales que pusieran de relieve las realidades a las que se enfrentaban los migrantes tras llegar a Chicago. Nos preocupaba que la mayoría de los medios de comunicación dejaran de informar sobre los migrantes al cabo de unas semanas, y queríamos ir más allá de los titulares y seguir a los migrantes mucho después de que el ciclo de noticias hubiera pasado a mejor vida.

Queríamos saber quiénes eran y cómo eran los inmigrantes recién llegados, de dónde venían y qué necesitaban. Queríamos saber qué esperaban encontrar al llegar aquí. Y esperábamos poder ayudarles a encontrarlo compartiendo sus historias.

Cómo nos reunimos

"Comenzó el primer día que estos autobuses empezaron a aparecer en la Union Station de Chicago. Mi colega Colin y yo habíamos intentado averiguar cuál era la respuesta de la ciudad, dónde se alojaban estas personas y cómo se les proporcionaban recursos, como alimentos, agua y ropa. Colin [Boyle] y yo, Diane [Bou Khalil] y Jesús [Montero] pasamos un par de tardes en Union Station saludando a la gente y enseguida supimos que queríamos empezar con una historia más amplia, algo más grande, que acabó convirtiéndose en After the Buses", Madison Savedra, de Block Club Chicago. explicó durante una mesa redonda sobre el proyecto.

Mesa redonda "After The Buses" con Block Club y Borderless

Block Club Chicago

En aquellos primeros días, los reporteros de Sin Fronteras iban a Union Station y repartían folletos a los inmigrantes recién llegados que decían en español: "¿Quieres compartir tu historia con un reportero? Envíanos un mensaje o llámanos". Muchos de los migrantes no tenían acceso a un teléfono móvil ni un número de teléfono. La idea era que cuando tuvieran acceso a un servicio, Wi-Fi o un número de teléfono estable, y estuvieran dispuestos a hablar, aún pudieran tener nuestra información a través del folleto.

Borderless continuó con su exhaustivo reportaje, aportando contexto y comprensión a lo que estaba ocurriendo mientras trabajábamos para conectar con nuestras fuentes.

Lo que hemos aprendido

Los migrantes con los que Borderless habló y los defensores que trabajaron con ellos estaban preocupados por la vivienda y el empleo a largo plazo, especialmente porque la mayoría de los migrantes tendrían que solicitar asilo. El proceso de asilo puede ser largo y difícil para muchos. Por ello, nuestra reportera colaboradora Chelsea Verstegen investigó el estado de los recursos legales y encontró una escasez de abogados de inmigración que lleven casos de asilo.

La mayoría de los inmigrantes con los que habló Borderless proceden de América Central y del Sur, principalmente de Venezuela, un país que ha sufrido una grave crisis política y económica que ha provocado escasez de alimentos y medicinas, un aumento de la inflación y mucho más. Borderless habló con la cofundadora de la Asociación Venezolana de Illinois, Ana Gil García, que ha estado al frente de la situación en Chicago, ayudando a los migrantes con sus necesidades inmediatas, como alimentos y ropa. En nuestro reportaje, Gil García explicó por qué 25% de la población de Venezuela ha abandonado el país y cómo los habitantes de Chicago acogen a los emigrantes venezolanos.

Mientras tanto, Borderless contrató a reporteros y fotoperiodistas que hablaban español y que también podían hablar con la gente sobre el terreno. Hablamos con la gente mientras subían a otro autobús para ir a los refugios del Ejército de Salvación o esperaban a que amigos que conocían en la ciudad fueran a reunirse con ellos. Los viajeros estaban cansados, agotados, confusos y necesitaban descansar.

En un reportaje anterior, en septiembre, hablamos con una familia venezolana de tres miembros.Keibel, de 26 años, y Eglianny, de 19, y su hijo Angel, de 2, que habían emprendido un viaje de tres meses desde Venezuela hasta Chicago. Recorrieron a pie y en autobús ocho países -Venezuela, Colombia, Panamá, Costa Rica, Nicaragua, Honduras, Guatemala y México- para solicitar asilo en Estados Unidos. Tras entrar en Estados Unidos, fueron trasladados en autobús de Texas a Chicago.

Los autobuses cargados de migrantes que habían llegado a Texas siguieron llegando a Chicago, y recibimos mensajes de personas que querían compartir sus historias con nosotros tras ver nuestros folletos.

Centrar a las personas en nuestras historias

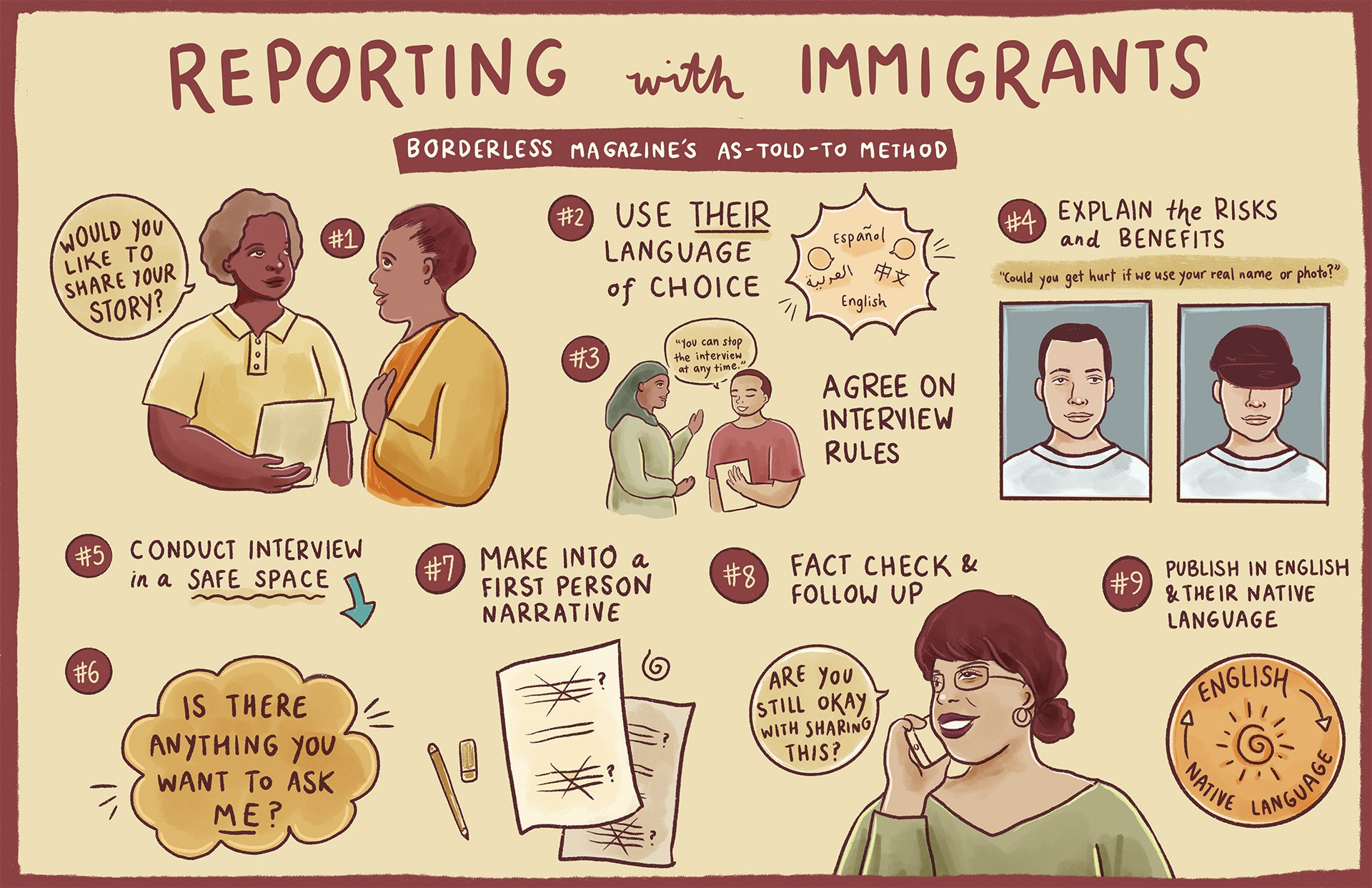

Borderless informó de sus historias utilizando nuestro Método As-Told-Toporque queríamos dar a los inmigrantes la oportunidad de contar sus propias historias, con su propia voz. Block Club Chicago también adoptó un enfoque centrado en el ser humano para sus reportajes, eligiendo elaborar perfiles de los migrantes a los que entrevistaron. Todas las entrevistas que hicimos para esta serie fueron en español, y ambos medios de comunicación confiaron en nuestros reporteros y fotoperiodistas hispanohablantes para que nos pusieran en contacto con las personas que se habían puesto en contacto con nosotros.

La reportera colaboradora de Borderless Ambar Colón dijo que el trabajo que hizo para Después de los autobuses era muy diferente de los reportajes en español que había realizado anteriormente.

"Ya trabajo mucho en español con La Voz. Pero éste ha sido característicamente diferente y me gusta el enfoque que le hemos dado. Me llevo muchas cosas buenas de esta experiencia que nunca olvidaré", dijo Ambar Colón.

Una cosa que nos diferenciaba de otros medios de comunicación era nuestro compromiso de ganarnos la confianza de nuestra creciente comunidad dedicando tiempo a conocer sus vidas, sus hogares, por qué los abandonaron y qué supuso eso.

Colin Boyle, fotoperiodista del Block Club, recuerda un emotivo momento que vivió con uno de los hombres que aparecen en el reportaje. Después de los autobuses.

"Estaba sentada con David, mi fuente, tomando un café, haciendo algunas comprobaciones y preguntas de seguimiento, y acabé traduciendo la historia [que había escrito] al español y se la leí. Enseguida se echó a llorar. Escuchar su propia historia y su propio viaje a través de una historia y volver a su lengua materna. Fue muy fuerte", dijo Colin Boyle, del Block Club Chicago.

Impacto

Nos hemos sentido abrumados por la respuesta de nuestros lectores, miembros de la comunidad y emigrantes recién llegados acerca de nuestra serie Después de los autobuses. En los días siguientes a la publicación, recibimos una mención del Los Angeles Times que calificó Borderless Magazine y Block Club Chicago de publicaciones "de lectura obligada". Y muchas de las personas que entrevistamos para Después de los autobuses manifestaron su agradecimiento por compartir sus historias. Denis "Omar" Covis nos envió un mensaje para decirnos: "Gracias por compartir mi historia. Espero que me ayude a encontrar un buen trabajo".

También oídas de Block Club que la serie inspiró a los miembros de la comunidad a recoger y donar 300 botas para los emigrantes venezolanos. Hemos recibido muchos correos electrónicos de personas que preguntan cómo pueden ayudar a los inmigrantes recién llegados este invierno.

Un agradecimiento especial a nuestros reporteros y fotoperiodistas hispanohablantes Colin Boyle, Ambar Colón, Alex V. Hernández, Jesús J. Montero, Madison Savedra, Jonathan Aguilar y Enrique Reyes por su trabajo en esta serie.