Photo courtesy of Selina Armenta

Photo courtesy of Selina Armenta For Mexican immigrant Selina Armenta, today’s Supreme Court decision on DACA means that her life can remain stable a little longer.

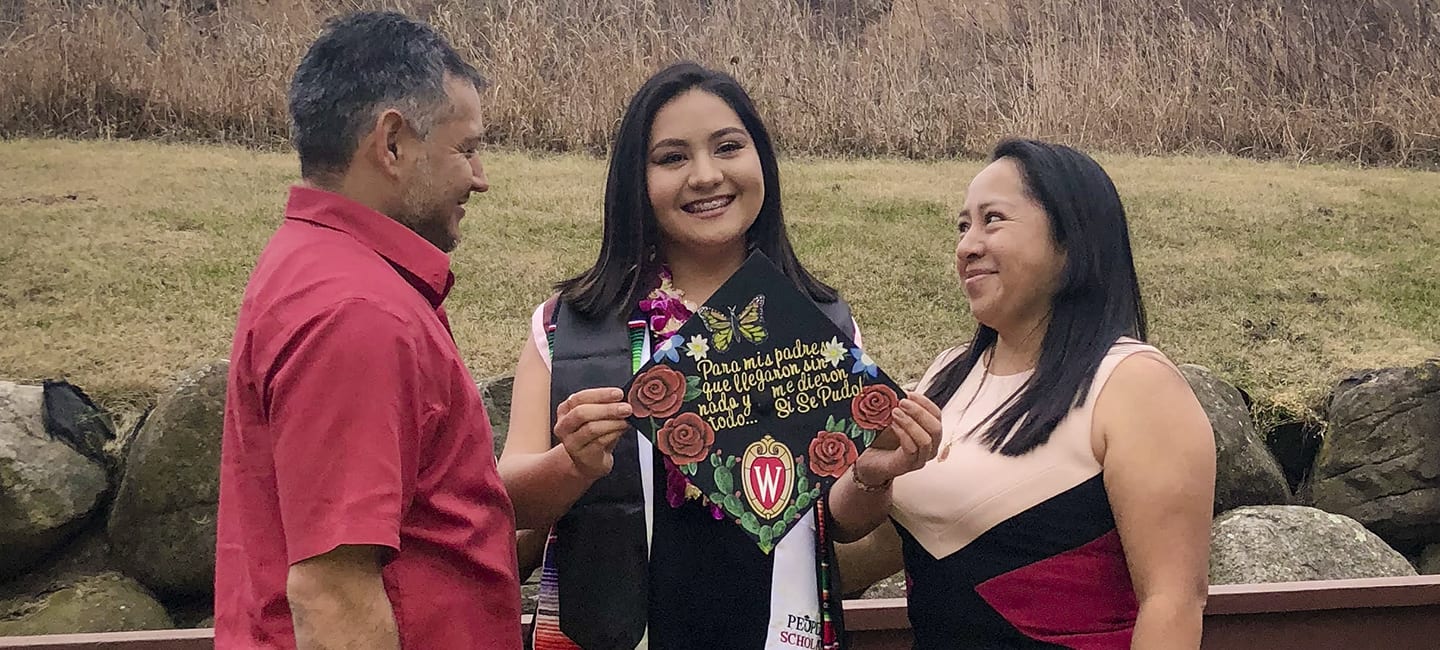

Above: Selina Armenta (center), her father Alejandro (left), and her mother, Rosario, at her college graduation celebration from the University of Wisconsin-Madison on Dec. 17, 2020, in Madison, Wis. Photo courtesy of Selina Armenta

The Supreme Court rejected today President Donald Trump’s attempt to end the DACA program. The Obama-era immigration policy has allowed over 825,000 immigrants to work and go to school in the United States since 2012.

For DACA recipients like 24-year-old Selina Armenta, the decision was an enormous relief.

Armenta came to the United States at the age of three from Queretaro, Mexico. Today, she is a college graduate from the University of Wisconsin-Madison and hopes to go to law school to become an immigration lawyer.

Armenta told Borderless Magazine what the Supreme Court’s DACA opinion means to her.

As soon as I read the decision, I got super emotional. My eyes started to tear up and I was overwhelmed with joy and relief. A huge weight was lifted off my shoulders, because now I can continue fighting for a pathway to citizenship for millions of us.

I’ve been on an emotional rollercoaster ever since Trump took office. You just never know what’s going to happen or when it’s going to happen. It’s been a lot of uncertainty. I feel like I’m in a constant state of anxiety because of that. It’s always something that’s on the back of my mind.

In 2017 when Trump wanted to end DACA I was in my last semester of college. It was a very hard time because I was like, “I’m getting done with school now. But what am I going to do without the ability to work in the U.S.?” I remember thinking maybe I won’t be able to go to law school in the U.S. and I’m going to have to move back to Mexico.

Selina Armenta Feb. 28, 2017 at the Supreme Court of the United States in Washington D.C. while on a trip with a friend. Photo courtesy of Selina Armenta

Moving back would mean letting all of my parents’ sacrifices go to waste. But leaving is a last resort for me. My parents did a lot so that I could be here now.

They decided to move to the United States from our home in Queretaro, Mexico as soon as they found out my mom was expecting me. They were teenagers and realized there would be more opportunities to work and a better environment to raise me in the United States. My dad came to Madison, Wisconsin first because he had cousins there. My mom left us to join him afterwards when I was two-years-old.

My grandparents were raising me while my parents were in the United States. The day I left Mexico I remember both sides of my family getting together to say goodbye. I came to the United States when I was three-years-old with my dad’s friend. He was a family acquaintance well known in my dad’s hometown.

The day I left I didn’t realize how permanent or how big of a deal it was to be joining my parents. All I knew was that I was going to go where my parents were. I didn’t know how far away it was or the fact I probably wouldn’t see my family in Mexico again for a long time.

When I got to Wisconsin I didn’t recognize my parents.

At that point I hadn’t seen my mom for a year and my dad for about two. I didn’t remember them and I was scared to be with them again. When I first got to Madison one of the first things we did together was go to the frozen lake and the state capital. I guess they were just trying to show me what they thought was important about the city.

Selina Armenta and her father, Alejandro, at Lake Wingra in Madison, Wis. in 1999. Photo courtesy of Selina Armenta

But I wanted to go back home where I was comfortable. I didn’t really realize it at first but it was pretty sad for them to see how much I missed Mexico.

In middle school I started to fully understand what it meant to be undocumented and the impact this had on me as a student. There were several times I couldn’t qualify for a certain school program or couldn’t participate in something because they requested a social security number or required that you were a U.S. citizen.

I was 10 in 2006 and took part in the May Day immigration march in Madison. I was shocked during the march to realize the size of the city’s undocumented immigrant community. I was still in middle school and it wasn’t something my friends and I were talking about. It’s not something that my parents were sharing with me in conversations.

I didn’t know how many people were in a similar situation. It opened my eyes to the size of the community and the magnitude of the issues affecting us. That’s when I started to get into immigration law and in high school decided I wanted to be an immigration attorney.

I applied for DACA right when I was eligible at 16. The most difficult part of the process was gathering all of the information needed for it. I remember looking for anything I had ever gotten from school showing I was a good student or in the United States at a certain point and time. We requested my entire K-12 school records from my district.

It was a nerve-racking process, because we had never done it before. No one had ever done it before. It was so new.

My parents and I also worried about releasing so much information to the government. What it could mean for all of us. But we decided it was worth the risk to pursue my dreams of becoming an immigration lawyer.

My status, my community and my experiences growing up have shaped my career inspirations. I currently work at a law firm where the Spanish speaking clientele is growing. As one of the few bilingual staff members I’m often speaking to those clients and translating or interpreting documents for them.

Selina Armenta on Sept. 28, 2019 in Milwaukee, Wis. Photo courtesy of Selina Armenta

If it weren’t for the Spanish speaking staff a lot of these clients wouldn’t be able to seek the legal aid they’re looking for. I’ve really enjoyed being able to bridge that gap with my Spanish speaking abilities. Just seeing the relief in a lot of people’s faces or hearing their relief over the phone. They realize someone at that office can talk to them and understand them. Not just the language but also our culture.

My DACA status is everything. Because of DACA I graduated college and was able to move out of my parents’ house and work at a law firm. Without my work permit I couldn’t survive and provide for myself. I couldn’t save up to go to law school.

I wish people understood the constant state of limbo that’s pretty much been my life since getting DACA. Yes, it has given people like me some stability but I still don’t have citizenship status. I’m not a resident and this is something that’s temporary I could lose it at any time.

DACA recipients on the frontlines shouldn’t be the reason why we were allowed to keep the program. And DACA still leaves out millions of immigrants like my parents. People who have helped build this country and deserve rights too.

I think the Supreme Court decision has set the mood. If we keep pushing for reform, I think it’s possible. It’s happening slowly, but I think eventually, we’ll get there. The organizing, the protesting, and the legal battles are showing some results.