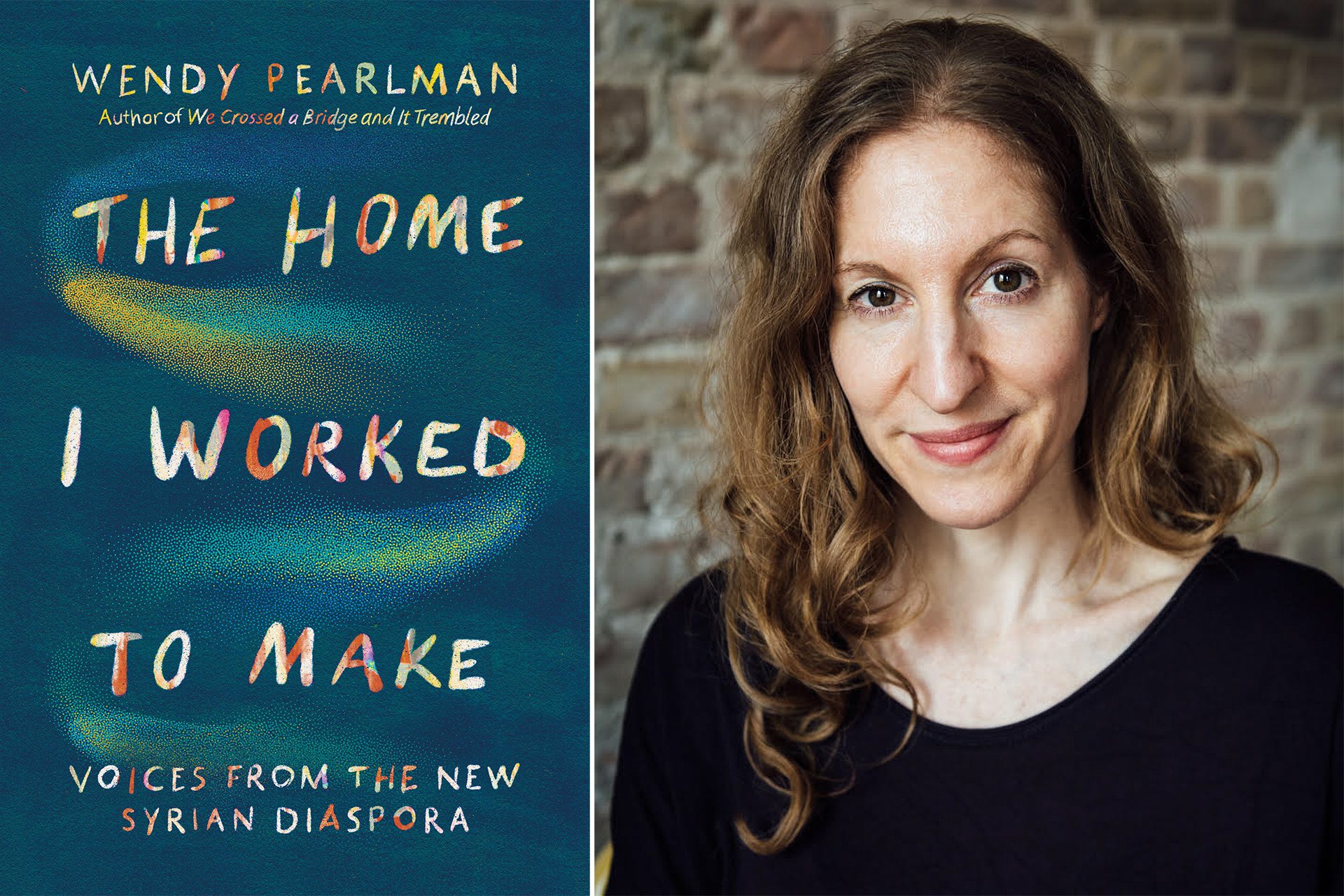

Courtesy of Wendy Pearlman

Courtesy of Wendy Pearlman In an excerpt from her new book, Northwestern University Professor Wendy Pearlman draws from interviews of Syrians who were forced to flee their homeland.

Excerpted from “The Home I Worked to Make” by Wendy Pearlman.

War forced millions of Syrians from their homes. It also forced them to rethink the meaning of home itself.

In 2011, Syrians took to the streets demanding freedom. Brutal government repression escalated their peaceful protests into one of the most devastating conflicts of our times, killing hundreds of thousands and displacing millions. As battles waned, the news cycle moved on. Yet for many Syrians, a new chapter was beginning.

Drawing on hundreds of interviews, The Home I Worked to Make presents the voices of dozens of Syrians who were forced to flee their homeland, following them as they make meaning from loss and attempt to find their place in a shattered world. With gripping immediacy, Syrians now on five continents share stories of leaving, losing, searching, and finding (or not finding) home. Their journeys—from Lebanon to Japan, Turkey to Australia, and many places in between—reveal both pain and triumph, demonstrating how violence and displacement transform the people who endure them. Some long for Syria, while others never want to return.

News that puts power under the spotlight and communities at the center.

Sign up for our free newsletter and get updates twice a week.

Some find rootedness in new friendships, faith, or trust in themselves. Others discover contentment with no roots at all. Across this tapestry of voices, a new understanding emerges: home, for those without the privilege of taking it for granted, is both struggle and achievement.

“A book for everyone in this progressively Syrianized world” (Yassin al-Haj Saleh), The Home I Worked to Make probes questions about home that are as intimate as they are universal. Recasting the “refugee crisis” as diaspora-making, it challenges readers to grapple with the hard-won wisdom of refugees and to see, with fresh eyes, what home means in their own lives.

Hani

Chicago, USA

They say home is where the heart is. I don’t believe that. Maybe for some people, the two go together. But they don’t necessarily go together for me. My heart is with my wife and my kid. My wife is from here. My daughter was born here. I love them. They’re the best thing that ever happened to me. But does that mean it’s home?

It could mean home in the future. But it doesn’t now. You can’t just decide overnight, “I’m going to make it feel like home.” Home is the details that you don’t think about until you lose them. The details that I lived with my whole life. Friends I can swear by. People who will always be there for me because we grew up together. We played soccer in the street together. Everyone came and watched the World Cup at our house because no one else had cable. The first PlayStation on the block was mine, so everybody came and played.

My elementary school. My high school. My seat in the library at college. Our bar in Damascus, Bab Sharqi, which was the best place ever. The store on the corner, where the guy gives me something and I pay him tomorrow because he knows who I am.

Have you heard of al-Fotuwa? Our soccer team. It meant so much to us. We’d go to the stadium four hours before the game because it was so much fun. Al-Fotuwa wins, and it’s the best day ever. Al-Fotuwa loses, and everybody is talking about what should they have done differently.

Read More of Our Coverage

When I think about home, I immediately go to the river. I think anybody from Deir ez-Zor would do that. Everything is built around the home I worked to make the river, and it was basically the highlight of the city. I used to go sit by the river when I escaped from high school. My friends and I would play cards the whole day. In summer, we swam every day. We’d grill and camp. At night, there is a bird that makes this noise. I remember that sound in my ear, even now.

All of these details. This is what makes it feel like home. They happened because of everything around them. Because of the community that we lived in. These details . . . you can’t create them. They create themselves. You can try to replicate the situation, but it won’t have that original feeling. It’s like if you went out and said, “I want to fall in love with a girl.” It’s never going to happen. It happens by itself. Home hap- pens like that. Details create themselves. Suddenly, you have that feeling: “I’m here.”

Finding home is also about reconciling with the past. If I learned one thing through everything that has happened, it’s to keep moving forward. I moved to Turkey with no money. I didn’t know anybody. I didn’t have any support system. I said, “I’m going to find myself a job.” And I did. I lost a lot of friends in those two and a half years in Turkey. I was working in the camps in Syria and everybody around me was dying. I’d cross the border into Syria and look for the section leader who was managing the tents, and they’d tell me that he died yesterday.

Now, I’m in Chicago. People aren’t dying all around me anymore. I try to find something that I can relate to. Back home, I went to the river. Here I go to the lake. Okay, Lake Michigan is not the Euphrates. But it’s a body of water. So, I go run by the lake. It means something to me. If we barbecue every day in the summer, we’ll make memories here too.

“Excerpted from The Home I Worked to Make: Voices from the New Syrian Diaspora. Copyright (c) 2024 by Wendy Pearlman. Used with permission of the publisher, Liveright Publishing Corporation, a division of W. W. Norton & Company, Inc. All rights reserved.”