A year after the Syrian uprising began, Northwestern University professor Wendy Pearlman headed to Jordan to collect the stories of Syrian refugees who were pouring out of their war-torn country.

A year after the Syrian uprising began, Northwestern University professor Wendy Pearlman headed to Jordan to collect the stories of Syrian refugees who were pouring out of their war-torn country.

Struggling to make new lives in often unwelcoming places, these refugees told her in brutally honest terms what it means to be Syrian today. For four years Pearlman traveled through Europe and the Middle East talking to former soldiers, dentists, and protesters whose lives had been upturned by struggle against the authoritarian regime in Syria.

The conflict and its downward spiral marked the death of the Arab Spring. Six million Syrians — over half of Syria’s prewar population of 22 million — have fled their homeland.

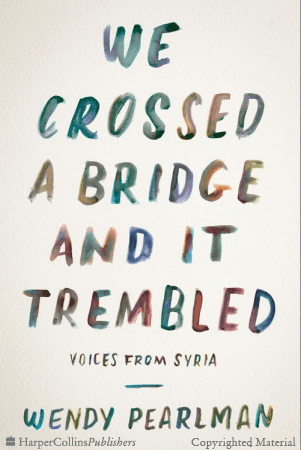

Pearlman shares stories from some of the 300 Syrian refugees she interviewed in her new book, We Crossed a Bridge and it Trembled: Voices from Syria. Through a patchwork of oral histories, Pearlman does what so few writers have achieved in covering Syria: allowing Syrians the space to tell their own tales.

Borderless hosted a panel with Pearlman, the Karam Foundation’s Lina Sergie Attar, and Northwestern University’s Danny Postel at Chicago Book Expo earlier this month. (A video of the event is available for viewing here.)

Now, Borderless is sharing some of the haunting voices Pearlman.

Fadi, theater set specialist, Hama

A Syrian citizen is a number. Dreaming is not allowed.

Iliyas, dentist, rural Hama

Syria looked like a stable country. But it wasn’t real stability. It was a state of terror. Every citizen in Syria was terrified. The regime and the authorities were also terrified. The more responsibility anyone had in the state, the more terrified he was. Brother didn’t trust brother. Children didn’t trust their fathers. If anyone said anything out of the ordinary, others would suspect that he was a government informant trying to test people’s reactions.

Every state institution recreated the same kind of power. The president had absolute power in the country. The principal of a school had absolute power in the school. At the same time, the principal was terrified. Of whom? Of the janitors sweeping the floor, because they were all government informants.

Jamal, doctor, Hama

It was impossible to get big numbers to demonstrate in Damascus. People were enormously afraid. So we’d mount “airplane demonstrations”: We’d chant for five minutes, then run away.

People came up with alternative ways of showing that they were against the regime. We would agree on a time and place, and then everyone would show up wearing the same color. For example, everyone would come to the same café wearing black. Nobody would say a thing; it was just a way of showing the size of the opposition. Eventually the security forces figured out what was happening and came after people dressed in the designated color.

If we’d listened to our parents, we never would have gone out at all. That generation lived through the Hama massacre of 1982. My generation is afraid — but not like them. I now say to my father, “Why were you silent all those years?” We say this to their entire generation.

Ziyad, doctor, Homs

Once, a young man entered one of the mosques in Homs. You could see a necklace around his neck, but the rest of it was tucked inside his shirt. He lined up and prayed with everyone else. And when he bowed, the necklace fell out. The pendant was a cross. People said to him, “Either you’re wearing that necklace by mistake, or you came to the mosque by mistake.” And the Christian young man said, “I came here to go out to the demonstrations with all of you.”

Amal, former student, Aleppo

Students were in the courtyard of the university, waiting for class to start. Someone started shouting, “God is great!” And then others joined in and started chanting, “Freedom!” I got goosebumps. I was with a friend and she grabbed my purse to hold me back, but I moved forward to join the demonstration. It was like I wasn’t in control of my own body, and my legs were just moving by themselves. My friend kept pulling my purse backwards, and I kept moving forward. The purse strap broke, and I merged into the crowd.

Abdel-Aziz, teacher, rural Daraa

For Jordan, Zaatari is a dead area. They found a place in the desert where not even a tree or an animal can live, and they put the Syrian people there. The other day we saw a butterfly in the camp. Everyone go so excited, we were all shouting at each other to come and look at it. It must have really lost its way if it wound up here.

Excerpted with permission from We Crossed a Bridge and it Trembled: Voices from Syria by Wendy Pearlman. Copyright © 2017 by Wendy Pearlman. Reprinted by permission of Custom House, an imprint of HarperCollins Publishers.