Mauricio Peña/Borderless Magazine

Mauricio Peña/Borderless MagazineDespite warnings, numerous hospitalizations and dozens of reports, Chicago officials continuously funneled thousands of migrants into an industrial warehouse that was never meant to house people.

Two pink socks and one tan sweater.

That was all five-year-old Jean Carlos Martinez Rivero left behind, according to the Cook County Medical Examiner’s records of his death.

The migrant boy, who officials say died from sepsis on Dec. 17 after falling ill at a city-run shelter in Pilsen, has become the symbol of Chicago’s struggle to provide adequate, safe housing for newly arrived immigrants.

News that puts power under the spotlight and communities at the center.

Sign up for our free newsletter and get updates twice a week.

An autopsy report obtained by Borderless Magazine found that when he died, Jean Carlos was sick with Streptococcus pyogenes (Group A) — also known as Group A Strep — as well as COVID-19, Adenovirus and the common cold. Sepsis, the body’s overactive response to a bacteria such as Strep, can be deadly if not treated immediately.

After the release of his autopsy, Chicago Mayor Brandon Johnson called Jean Carlos’ death a “tragic loss” and reiterated the city’s past statements on how the boy received immediate medical care and how “[all] shelter residents are offered comprehensive medical examinations and care.”

But a Borderless investigation into the Pilsen shelter, released just days before the five-year-old died, along with new documents obtained by Borderless, paint a very different picture. In the weeks leading up to his death, migrants made at least 17 grievance reports to the Office of Emergency Management and Communications (OEMC), decrying spoiled food, the rationing of water and mistreatment from staff.

In formal complaints to the city and in interviews, migrants say shelter staff did not take their medical concerns seriously. When Jean Carlos became seriously ill, a migrant told reporters she saw him convulsing in the shelter’s bathroom. She said shelter staff prevented her from giving the child CPR.

While the city has taken steps to improve the quality of food and access to clean water for migrants living at the Pilsen shelter since Jean Carlos’ death, eight migrants Borderless spoke to say little has changed since December.

“The changes are temporary,” one migrant woman told Borderless in mid-January. “And then it goes back to being the same.”

Over Two Dozen Warnings

In early December, more than a dozen migrants detailed inhumane living conditions in the Halsted shelter, located at 2241 S. Halsted Ave., including freezing temperatures and unsanitary bathrooms. The shelter is a former factory complex that is part of a Planned Manufacturing District, which city zoning laws prohibit for residential development. The city opened the complex as a shelter in early October, telling nearby residents it would hold up to 1,000 migrants. By December, over 2,300 people lived there.

Inside the shelter, migrants described outbreaks of various illnesses — including chickenpox, the flu and upper respiratory infections — spreading without sufficient medical care. More than a dozen migrants who spoke to Borderless, as well as videos taken inside the shelter that Borderless reviewed, showed that the facility failed to meet the basic standards for emergency shelter laid out by the U.N. Refugee Agency.

“There is no medicine,” one woman told Borderless in mid-December, just days before Jean Carlos’ death. “For those who aren’t working, we are out on the street asking for help to buy medicine. At the moment, my husband is sick. He has a throat infection [and the flu]. They checked him out, but they didn’t give him anything. No antibiotics. No pain reliever.”

Concerns about the safety of the shelter were brought to city officials just weeks after the shelter opened, according to emails obtained by Borderless Magazine.

On Oct. 28, Ald. Nicole Lee (11th Ward) notified Mayor Johnson, Department of Family and Support Services Commissioner Brandie Knazze and other top officials of the shelter’s dangerous conditions. Lee detailed concerns about exposed pipes with raw sewage, a cockroach infestation, a possible outbreak of illnesses, insufficient meals and water and mistreatment of migrants by shelter staff. WTTW was the first to report on the emails.

In response, Knazze said contractors had added more bathrooms, cots were relocated away from sewage drains and the city was working with Cook County Health to expand medical coverage. While Knazze wrote that she was unaware of any mistreatment from staff and urged residents to submit grievance reports to OEMC, a grievance report submitted weeks earlier on Oct. 8 had already detailed poor treatment by shelter staff.

“We are being denied water,” the report says in Spanish. “Food is bad. We are mistreated by staff. We are dying from the cold. The heater doesn’t work. We should be relocated or given housing assistance.”

Read More of Our Coverage

When the emails from Ald. Lee were made public in January, Mayor Johnson defended the city’s response, saying they took “immediate action” after they received the emails in late October. But in the weeks following the emails, serious illnesses continued to spread through the shelter, and migrants filed over a dozen formal complaints about the shelter’s conditions, according to reports reviewed by Borderless Magazine.

In the month of November alone, at least 16 migrants were transported to hospitals with severe medical conditions. These included a four-year-old who experienced chest pain, a fever and body aches; a resident who had facial droop; and a resident with a high fever who couldn’t feel their hands and feet.

Migrants submitted at least 17 grievance reports about the Halsted shelter between Oct. 8 and Dec. 31. The day that Jean Carlos died, a parent with a child who had a fever of 103 F complained that a shelter staff member had canceled their call to an ambulance “because he said he didn’t see the kid sick.”

“They laughed in my face,” the grievance reads in Spanish. “Please, we are human beings … Today, there was a child who died here because he had a fever for days.”

The next day, another migrant listed a number of complaints about the food and mistreatment from staff. “They keep us as prisoners,” the migrant wrote in Spanish. “We can’t say anything to them because they reprimand us. And yesterday, a child died due to negligence.”

More than 20 calls were made to 911 from the Halsted shelter on Dec. 17 and 18, according to OEMC records.

The Death of a Child

Jean Carlos was a healthy boy — big for his age — and with clean fingernails, according to the autopsy report. Like many migrants staying in the city’s shelter system, he and his family would sometimes beg for money on the street so they could buy additional food.

Jean Carlos was sick with a fever for two or three days before his death, according to a police report obtained by Borderless Magazine.

On Dec. 16, Jean Carlos’ parents gave him Tylenol and what they were told was ibuprofen to help with his fever. The following day, he woke up asking for food. After eating breakfast, the family spent the day panhandling before Jean Carlos said he wanted to return home because he wasn’t feeling well. After having electrolytes, his parents said he immediately vomited.

When the family returned to the shelter, they notified the staff that Jean Carlos’ lips were purple. A staff member said it was probably because of the cold weather, according to an unredacted police report obtained by Borderless Magazine.

Around 2:45 p.m., the boy said he was bloated and needed to use the restroom before collapsing and having a seizure. Shelter staff called for an ambulance after the mother screamed for help.

A migrant woman, who asked to remain anonymous for fear of retaliation, told City Bureau reporters that she walked into the bathroom with her son that afternoon. She said she witnessed Jean Carlos’ mother pouring water on the five-year-old’s head to cool him down from the fever before he collapsed and started convulsing on the floor. The migrant said the nervous mother passed her son to a man who placed the boy on a table. While the mother screamed for help, shelter staff closed the bathroom door, preventing anyone from coming in or leaving, the migrant said.

Read More of Our Coverage

The migrant woman, who is trained in CPR, offered to perform CPR on the boy but was told by shelter staff not to touch the child because it wasn’t “safe.” Favorite Healthcare Staffing, which is contracted by the city to run the shelter, did not respond to Borderless’ questions about whether migrants were prevented from performing CPR.

Jean Carlos was transported to the University of Chicago Comer’s Children’s Hospital alone. His parents weren’t allowed in the ambulance, and the police later took them there. He was pronounced dead at the hospital, according to the police and autopsy records.

In a Dec. 19 statement, the Chicago Department of Public Health said that Jean Carlos did not appear to have died from an infectious disease. The department stated there was no evidence of an outbreak, and the other people hospitalized from the shelter did not appear to be related. An official autopsy has since shown that the boy did, in fact, have several infectious diseases.

Earlier this month, the Cook County Medical Examiner said Jean Carlos died of sepsis from Strep. The autopsy report shows that COVID-19, Adenovirus, and the common cold were also contributing factors. Sepsis is a life-threatening emergency and requires immediate medical attention. The illness occurs when the body’s immune system has a severe reaction to an infection, which can lead to organ failure and death. “The best way to reduce the risk of sepsis is to avoid infections,” have good hygiene, avoid unclean water and unsanitary toilets and eat a healthy diet, according to the World Health Organization.

According to research published in the journal Critical Care Medicine, “the risk of death from sepsis increases by an average of up to 7.6% with every hour that passes before treatment begins.”

“It’s Still the Same”

A week before Christmas, several dozen local, national and international outlets descended on the shelter to cover Jean Carlos’ death.

Some captured footage of first responders taking shelter residents by ambulance, while others interviewed migrants describing the mistreatment from staff, poor food and rampant illnesses spreading behind closed doors.

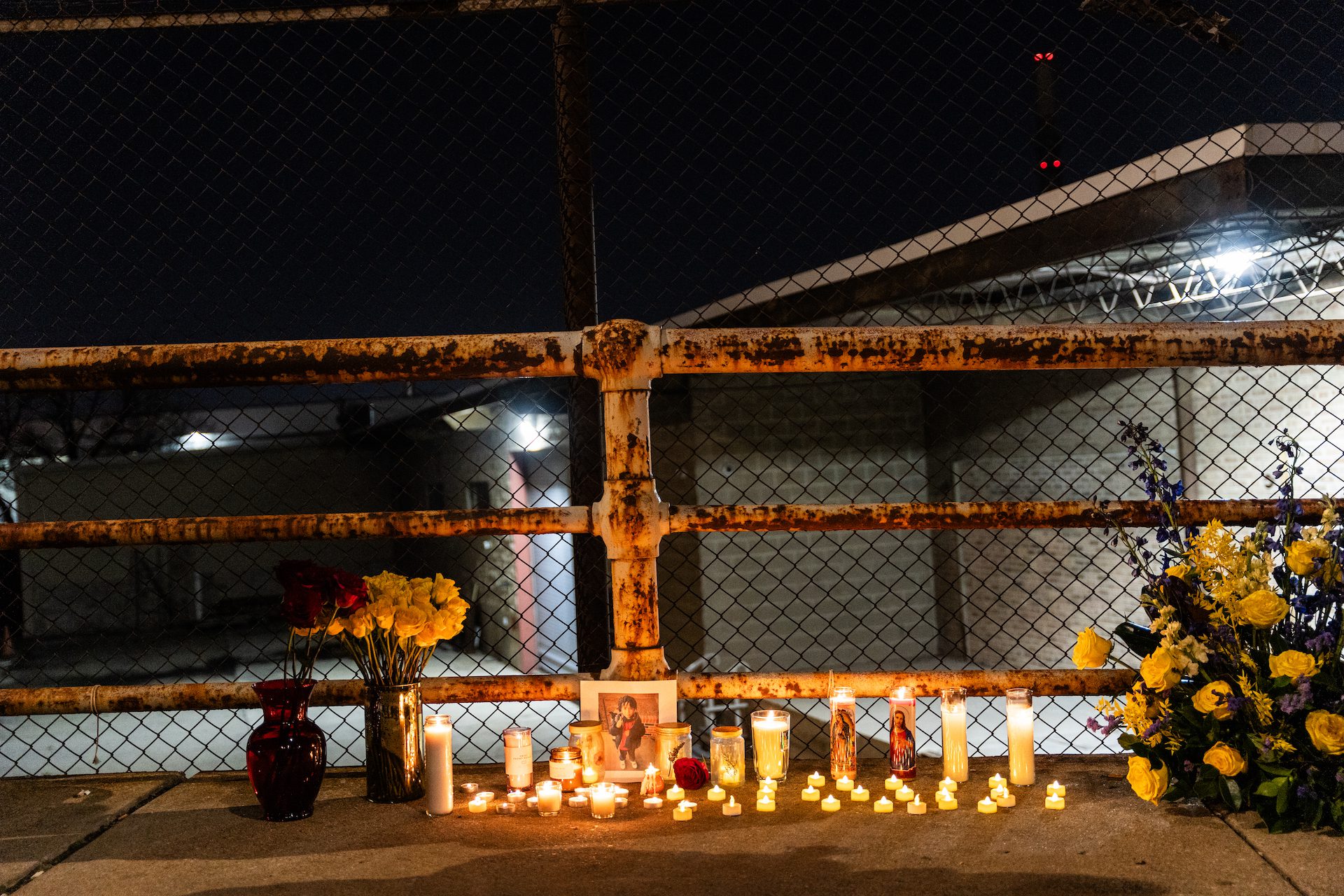

On the frigid evening of Dec. 20, hundreds of mourners gathered across the street from the Halsted shelter to grieve the loss of the five-year-old.

“This was a preventable death. And it was 100% expected,” said Britt Hodgdon, a social worker who volunteers to support migrants, at the December vigil. “We knew this was coming. We’ve been raising the alarms for months and months and months.”

In an email obtained by Borderless, members of the Mobile Migrant Health Team, a volunteer group of doctors and medical students providing medical care to migrants, emailed Johnson and other city officials after Jean Carlos’ death, pleading with them to allow volunteer medical providers into city-run shelters.

“We ask that you, Mayor Johnson, take stock of the resources we present and utilize them to address the most urgent needs,” the email reads. “We will continue to meet with other organizations and coordinate further. These are the two most rapid solutions to prevent death.”

In mid-December, city officials launched a multi-department investigation into Jean Carlos’ death. But months later, the full investigation findings have yet to be shared publicly.

Asked about the conditions at the Pilsen shelter, a mayor’s office spokesperson told Borderless on Monday that the city was “constantly assessing how to improve conditions” across the city’s shelter system.

City officials said they have made a number of changes at the site, including expanded health screenings and vaccinations with the Chicago Department of Public Health, Cook County Health and other federally qualified health centers. The city has also worked with food providers to improve food quality and they have remediated sewage pipes. They also added water bottle filter stations and heat and smoke detection systems to the shelter.

In a statement on Monday, Favorite Healthcare Staffing said it followed a “standard grievance procedure” for employees.

“Favorite does not tolerate or accept discriminatory or abusive behavior by its staff, and expects all staff to treat shelter residents with respect and care,” Favorite Staffing spokesperson Keenan Driver said in a prepared statement. “Complaints are investigated and any verified via the grievance process are addressed, including up to termination.”

In a similar statement, city officials said city-run shelters follow an anonymous grievance process for new arrivals. The city said it did not tolerate discrimination or abuse, and any substantiated reports would result in corrective action, including termination. They noted DFSS officials and security personnel are regularly visiting the shelter.

“Please, we are human beings … Today, there was a child who died here because he had a fever for days.” – Migrant in official grievance report submitted Dec. 17

In the weeks and months since Jean Carlos’ death, several migrants noted slight improvements to food and fixed heating conditions. One migrant who left the shelter in December said that she saw changes come quickly after Jean Carlos’ death. She said more doctors would come to the shelter, the food improved, a playground was built for children, and if a child was sick, migrants were provided with thermometers to check their temperatures.

But others told Borderless that shelter staff continued to treat residents poorly in January and February, frequently threatening to kick people out for taking videos or photos. They also said bathrooms remained unsanitary. One man said they had to ask staff for toilet paper before going to the bathroom.

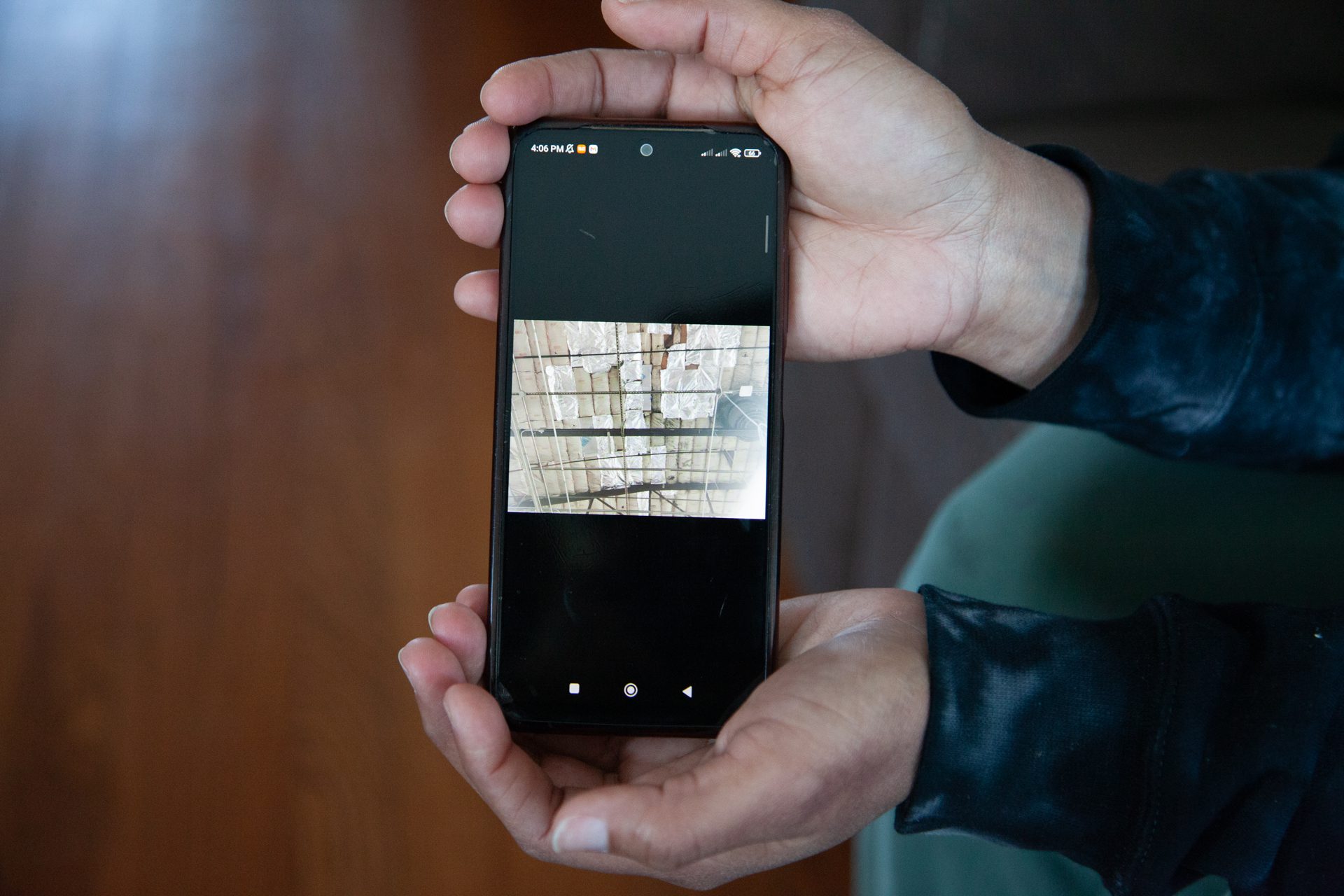

Another migrant expressed frustration about construction work taking place around beds, with dust raining down on small children. In one video shared in January with Borderless, a worker wearing a mask is seen working on the floor in the middle of cots as small children play nearby.

On a recent Friday afternoon, nearly a dozen vendors line the sidewalk selling arepas, soup and other Venezuelan street foods as semitrucks and cars zoom past. As several migrants make their way in and out of the shelter, a young couple leaves the building with two small boys following closely behind.

The couple, whom Borderless is not identifying for fear of retaliation, said life in the shelter has been challenging from the day they stepped inside in early October.

Like the dozens of migrants who have spoken with Borderless since December, the couple listed familiar concerns: poor sanitation, mistreatment from staff and a lack of adequate medical care amid many illnesses.

“Sigue igual,” the man said in Spanish, while his wife nodded. “It’s still the same.”

The FOIA Bakery contributed documents received through the Freedom of Information Act that were used in the reporting of this story.

City Bureau Senior Reporter Sarah Conway and City Bureau Civic Reporting Fellow Sebastián Hidalgo contributed reporting to this story.

Support for this investigation came from the Fund For Investigative Journalism.