Michelle Kanaar/Borderless Magazine

Michelle Kanaar/Borderless MagazineImmigrant rideshare drivers are backing a proposed Chicago law that could raise driver pay and give them an appeals process when working for Lyft or Uber.

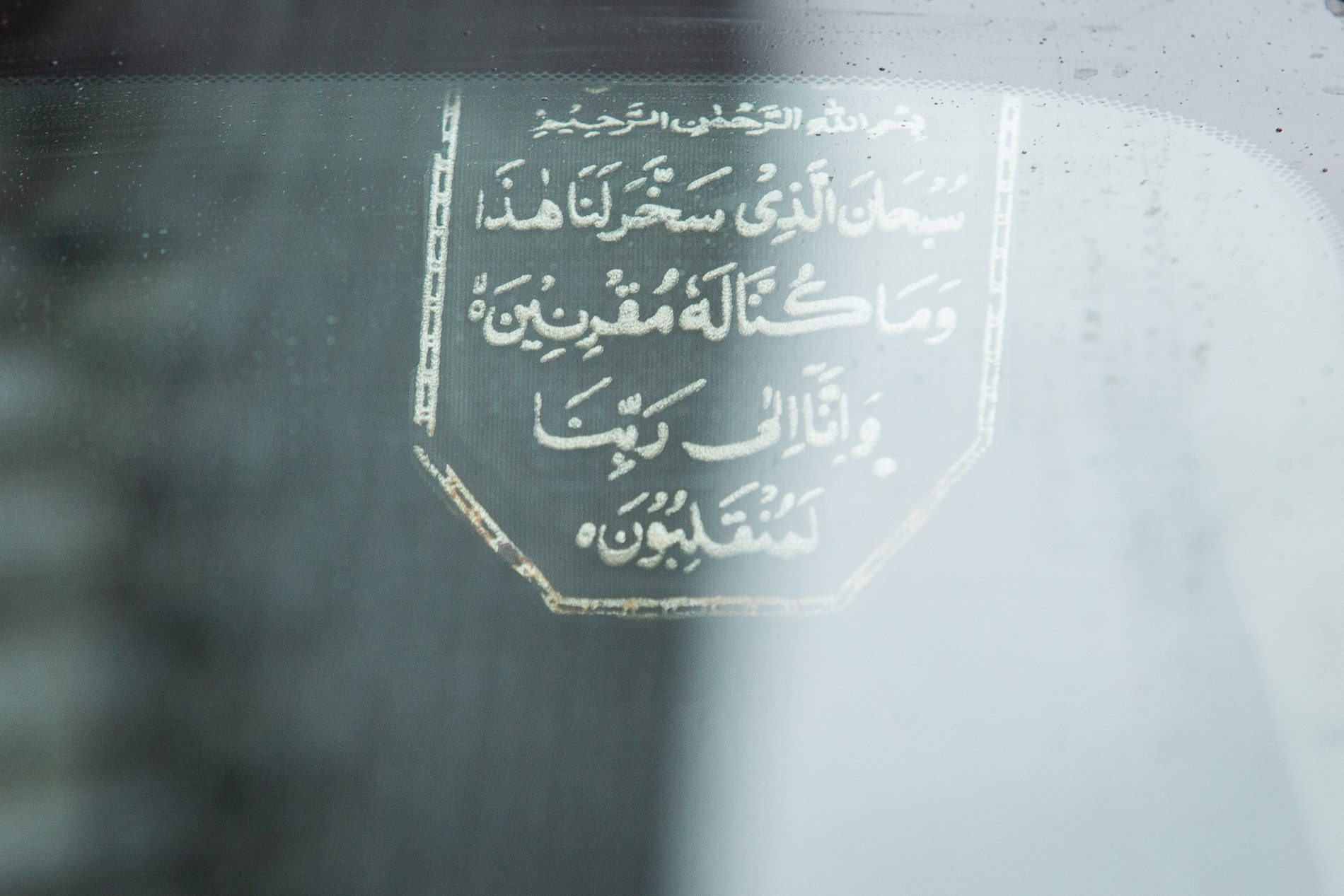

Naveen Ali worked as a rideshare driver for more than six years. The 45-year-old, originally from Pakistan, had a five-star Lyft rating and completed more than 10,000 rideshare drives. In one review, a rider proclaimed her “the nicest Uber I’ve ever had.” Another wrote that they “would absolutely be honored for her to drive me again.” Yet another noted, “I hope I get her as a driver the next time I need a ride.”

News that puts power under the spotlight and communities at the center.

Sign up for our free newsletter and get updates twice a week.

But none of that seemed to matter when, in October 2019, Ali was abruptly kicked off the Lyft app after a rider accused her of physical assault. Ali said she acted in self-defense because the rider became physically aggressive. A few months later, Uber deactivated her account, leaving her with no source of income. She couldn’t find a way to contest either deactivation although she tried calling and texting Lyft and Uber through their customer service lines.

Ali is just one of a growing group of rideshare drivers in Chicago — many of them immigrants like her — who have lost their jobs through rideshare apps’ deactivation processes. Currently, apps can ban drivers with no warning or appeals process. But this may change with the Chicago Rideshare Living Wage and Safety Ordinance, a legislation that will be introduced in the City Council today. If implemented, it would introduce a slew of new rules, including one that would create a fairer and clearer deactivation process by allowing drivers a chance to contest complaints. The legislation also includes higher safety standards, minimum pay and a cap on the portion of fares companies can take from rides.

More than 2,000 rideshare drivers, united by the Chicago Gig Alliance, a gig worker advocacy group, are backing the ordinance.

“This is really popular work with people who are immigrants, but also there’s no protection,” said Lori Simmons, a former rideshare driver and organizer with the Chicago Gig Alliance. “So as a person who’s an immigrant, you’re going to be faced with more vitriol than the average citizen. I mean, we just know that’s true. And because of the way that the app works, there’s no due process. There’s no process to actually file a complaint and have it be checked out. It does not work in a person’s favor if they’re an immigrant.”

About 70% of people who work in the gig economy are people of color, according to a recent Pew Research survey, and many are immigrants. “It is a preponderance of these folks who are using these apps, and the amount of justice that you can get is just … it’s nonexistent,” Simmons added.

Currently, rideshare apps permanently deactivate drivers based on a range of safety issues and mostly due to customer reports. The city of Chicago then requires rideshare companies to report these permanent driver deactivations to the Department of Business Affairs and Consumer Protection. The city does not publicize specifics about why a driver was deactivated, only that the deactivation was related to a safety issue. Drivers banned from their first platform generally aren’t able to work with another rideshare app.

According to a Lyft spokesperson, if a driver’s account is deactivated for certain safety reasons on another platform, the city alerts Lyft of the deactivation and Lyft also deactivates the driver. Uber did not respond to comment, but according to its website, it follows a similar process.

“We take safety reports from riders and drivers extremely seriously and investigate each one to determine the appropriate course of action,” a Lyft spokesperson told Borderless Magazine. “If a driver disagrees with the action taken, they can ask for the decision to be reviewed. If the driver is found to have been in violation of our Community Guidelines, they are removed from the platform for the safety of the community.”

Ali was deactivated from the app in October 2019, when a rider gave her trouble for coordinating a pick-up of another customer for a shared ride. The situation escalated as Ali refused to not pick up the other person. Eventually, the rider yelled at Ali and reached forward to grab her phone.

“She tries to scratch me right here,” Ali said, pointing to her right bicep. “And I tried to move her back, because I don’t know what she has, what she has in her head or nothing. Anyway, so I go, I opened the door. I said just, ‘Out.’”

Ali said she batted the customer away then called the police. But the customer reported her to Lyft for physical assault, and when that information was shared through city channels, Uber deactivated her as well.

“[It was] not a fair process,” Ali said. “They don’t show me the city’s letter, if the city [even] sent anything. They are not in contact with me. Like Lyft didn’t, Uber didn’t contact with me. They just disconnected. I go so many times, ‘Hey, what’s happened?’”

Although Ali asked Lyft to reconsider her deactivation, the accusation leveled against her may have been deemed too severe for the company to reactivate her account. Unable to drive, she could not pay for rent, groceries, car payments and phone bills. Shortly after she was deactivated from both apps, she lost her apartment and was forced to sleep in her car for a few days before staying with friends from her mosque.

“I’m not saying I’m perfect,” Ali said. “But if you see my driving record, no ticket, no nothing … At least give me a fair chance to talk.”

Khawaja Lateef, a 62-year-old from Pakistan, also drove for Uber as his main source of income. Lateef drove for around three years before the app deactivated his account in October 2021. He had picked up two passengers from a bar one night, and one of the passengers accidentally put in the wrong address, Lateef said, then argued with him when he drove there. Uber booted him from the platform a few days later.

Uber never gave him a clear reason, saying only that there was a security issue.

Then, Lateef registered as a Lyft driver and followed what he thought was the correct process, reviewing his records with the city. But when he opened the Lyft app, he said the screen flashed a message: “You’ve been deactivated.”

During his time with Uber, Lateef was able to accumulate some savings. Now, he’s quickly spending them as he continues to look for a job.

Immigrants face unique challenges as rideshare drivers, as they balance the need to pay their rent and feed their families with the bureaucratic hoops required to drive for Uber or Lyft. Both companies require drivers to have a valid U.S. driver’s license and Social Security number, for example, something that newly arrived immigrants looking for work don’t always have.

Miguel*, a father of two originally from Mexico City, started driving for Uber as an undocumented worker so he could support his family. Using a false Social Security number and a temporary visitor driver’s license, he drove for more than a year without complications. Then, in 2021, Uber temporarily deactivated him twice for issues related to the temporary license. The second time, representatives told him that he’d be able to drive again once he had the correct documentation. Soon after, he became a permanent resident and upgraded his documents, thinking that Uber would reactivate his account.

Read More of Our Coverage

He also drove for Lyft, which also deactivated his account. Miguel struggled for two months without work or any kind of income before eventually obtaining a factory job. He still does not know why he is unable to drive.

“If they said, ‘You were doing fraudulent activity back,’ then, well, OK. I’m gonna agree,” he said. “But why this time? I want to fix everything. And they say this is fraudulent. So I don’t get it.”

Drivers like Ali, Lateef and Miguel say that the rideshare ordinance would serve as a long overdue check on rideshare apps that have largely operated with little government regulation in Chicago. Drivers would be able to contest deactivations, and all appeals would follow a formal procedure through the city’s Department of Administrative Hearings.

The proposed ordinance “would empower the commissioner for BACP [Business Affairs and Consumer Protection] to create an appeals process for drivers,” said Alderman Daniel La Spata (1st Ward), a supporter of the ordinance. “Whether it’s viewed as warranted or unwarranted suspension, the commissioner would be given the powers to create rules and regulations around this kind of an appeals process.”

The ordinance would also establish a slew of other rules, including a minimum per-minute, -mile and -trip pay; higher pay for rides that leave the city limits; a cap for the cut that rideshare companies can take from each fare; more transparent fare breakdown for both drivers and passengers and enforced identity verification for passengers. It would still hold drivers accountable for their actions, but it would provide a buffer, notifying them seven days in advance of any suspension and informing them of their right to appeal.

“Yes, you do want to keep people safe,” said Simmons of the Chicago Gig Alliance. “Of course, you don’t want somebody who’s violent or committing crimes to be on these apps. But some of these accusations are so severe that you really would expect there to be some sort of follow-up.”

The ordinance is similar to other policies already in place in Seattle and New York City, where rideshare drivers have the right to appeal deactivations through an appeals process.

Now, Ali makes a living delivering food orders for Grubhub. Every day, she sets out with a goal of making $150 — enough to pay for rent and other necessities. On a recent Wednesday, she made just $66. This isn’t out of the ordinary — she often makes below that $150 benchmark, but days like Valentine’s Day or storms can make up for it.

She misses rideshare driving, not only for the better pay but also for the experience of driving around Chicago and meeting different people.

“I love driving. I love to see the places,” Ali said. “I love to talk, you know, I learn different things from different cultures and experience so many things … Every time, every person, I learn something new. I love to drive Uber. If I could start tomorrow, I would start tomorrow.”

*Name has been changed for safety reasons.