Max Herman/Borderless Magazine

Max Herman/Borderless MagazineChristopher Lorenc’s family lived in displacement camps after fleeing war-torn Poland. They resettled and made their home a haven for other Polish immigrants in Chicago.

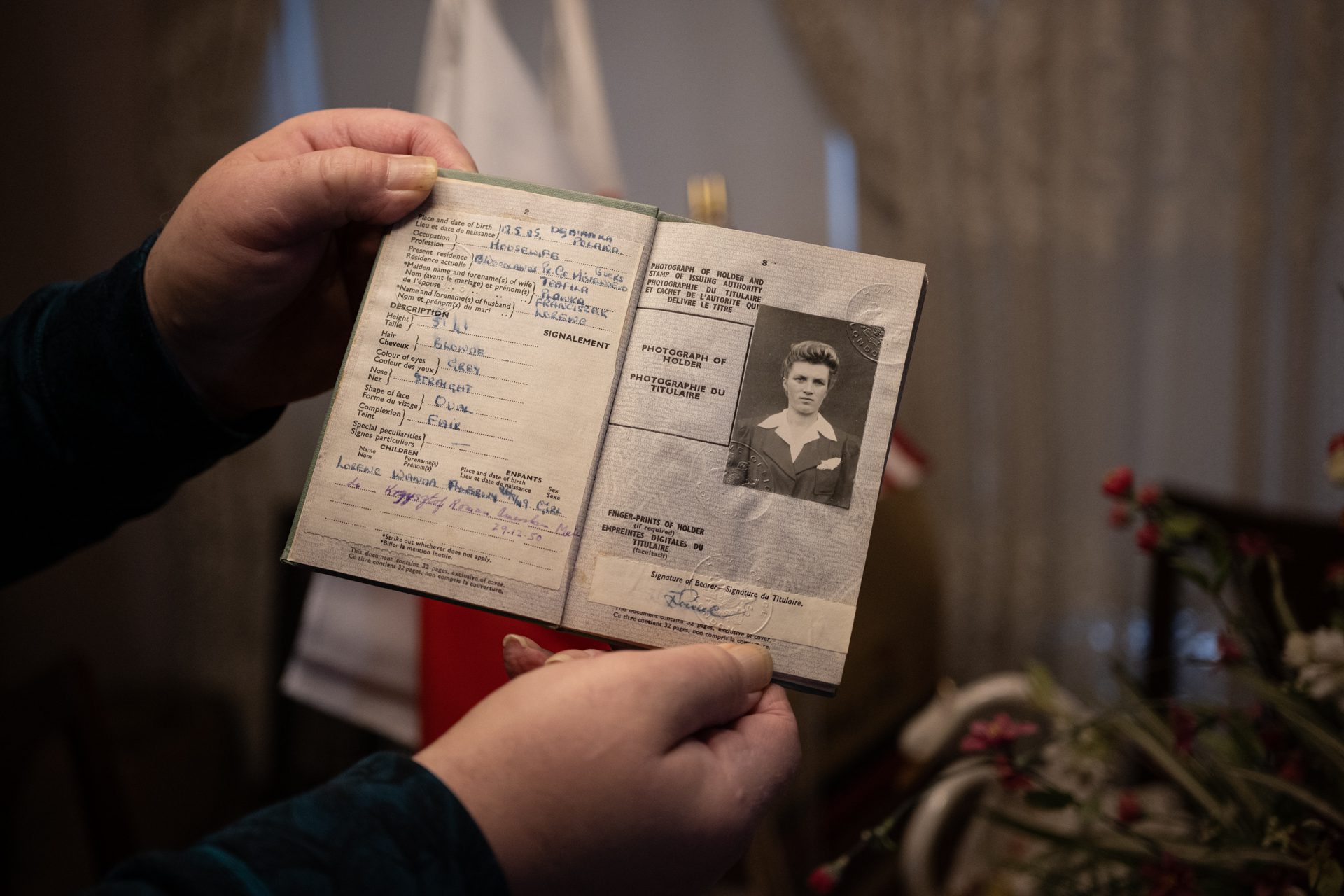

Inside his childhood two-flat apartment in Belmont Cragin, Christopher Lorenc flips through photo albums and travel documents spanning most of his life. He occasionally pauses on a photo to reminisce about a memory of his family’s journey from Poland to the United States.

“My father and mother were the patriarch and matriarch of the family, of all the cousins – I’ve got about 20 first cousins,” Lorenc said.

“My parents met in England and married in 1947. It took them five years to get a visa to come to the U.S. At that time, my sister and I were born in a rundown shelter, he said, pointing at a photograph of his parents standing outside a displacement camp while holding Lorenc as a nine-month-old infant.

News that puts power under the spotlight and communities at the center.

Sign up for our free newsletter and get updates twice a week.

Lorenc was a young child when his family arrived in the United States. His family fled Poland during World War II, surviving in displacement camps before settling in Chicago — a welcoming port of entry for Polish families.

Now 73, Lorenc reflects on his family’s immigrant journey and the house and cherished mementos that have kept him rooted in his Polish heritage.

Displaced By War

My parents came from Lviv, which was then part of Poland. When the Germans invaded Poland in 1939, the Soviets expatriated many people out of their villages. My grandmother [mother’s mother], Aniela, had three young daughters and was given an hour to pack whatever she could. She grabbed some potatoes and onions, and the children boarded a train to Siberia. There was no meat — all the men took it — they needed to fight.

In Siberia, my family lived on scraps. My grandmother fed her children from the little she brought. My father, Franciszek (Frank), was also taken to Siberia, where he joined the Polish Army, which was organized, trained and supported by the British.

My father fought in Italy, including at Monte Cassino. It was one of the worst battles of the war. It was absolutely a terrible onslaught. The Allies tried three times to breach a hill fortified by the Nazis. Finally, the British and a ragtag group of Poles, Australians and New Zealand soldiers managed to take the hill.

After the war, my parents moved to England, where they waited five years in a displaced persons camp for their visas to the United States. We came through Queen Mary, a ship that was famous for being so fast.

Building A Life In Chicago

My family immigrated to Chicago in 1951, sponsored by my great-uncle, Alec. We settled in a small apartment in Wicker Park. The place was in poor condition, and it took my parents months to renovate the apartment despite being renters.

My uncle babysat us for a couple of years until we became familiar with everything in the city.

The turning point came when my parents, aunt, and uncle purchased a two-flat building in Belmont Cragin. This home isn’t just a house—it was the foundation of my family’s stability and resilience. My aunt and uncle lived upstairs, and my parents lived on the first floor. We split the costs and took care of each other.

Life as an immigrant was tough. My father worked as a machinist apprentice, making just over a dollar an hour. My mother worked in factories, enduring awful conditions. My mother said it was so hot in there that women would faint right at their workstations. But they kept going to give us a better life.

The house symbolized more than financial prudence. It became a hub for our family and others in need. Over the years, my parents sponsored about ten people from Poland, giving them a temporary home, helping them find work and supporting them until they could stand on their own. Some stayed in Chicago, while others returned to Poland to begin anew.

Growing Up As An Immigrant In Chicago

I remember the subtle and overt discrimination my family faced. People called us ‘DPs’—displaced persons — and mocked us. Adults making fun of kids—I couldn’t understand it. But we didn’t let it stop us. My parents taught us to focus on hard work and education.

For me, childhood was both joyful and challenging. When we arrived, my sister and I didn’t speak a word of English. We attended Catholic school at St. Hedwigs, where the nuns insisted we learn English quickly. It was tough at first, but I was speaking English fluently by the second year. A lot of the language I learned was from television.

I graduated from college, majoring in Mechanical Engineering, and started earning a decent income as a vice president. I moved to the suburbs for several years but returned to our family’s home when my mother’s health took a turn for the worse.

Read More of Our Coverage

Inside the two-flat, we worked tirelessly to preserve our Polish heritage. The kitchen was the heart of the home, where my mother, Phyllis, spent hours preparing traditional dishes like pierogies and kapusta, a cabbage stew. When she made pierogies, the whole family would come over. It wasn’t just food — it was a way of keeping our culture alive.

Even today, I try to cook some of my mother’s dishes. When we have family gatherings, everyone asks me to bring my version of kapusta. It takes me about eight hours, but I can make a version that’s very close to my mother’s. The dish connects me to my mother and our roots.

Caring For Family Until The End

My childhood home also became a space for caregiving as my parents aged. My father passed away 15 years ago after battling cancer and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. He had been a heavy smoker, a habit from his army days when cigarettes were given to soldiers to suppress hunger.

He was part of a group called ‘Karpoczynski,’ which was made up of veterans of that battle in Monte Casino. Some of the members called me and attended my father’s funeral. They honored his memory with the medals he received and prayed for his soul.

My only sister, Wanda, passed away at 68.

My mother lived to 91 despite a decade-long battle with dementia. She needed constant care. It was hard, but it’s what you do for your family. Toward the end, I had to place her in a nursing home. It broke my heart because you don’t do that in our culture. But I had no choice.

Though the house is quieter, its walls hold decades of stories, sacrifices and triumphs. It’s where I cared for my parents, hosted family gatherings, and now trying to preserve it.

A Changing Neighborhood

The neighborhood around our house transformed over the decades. When we moved in, the neighborhood was home to Polish and Italian immigrants. Over time, as gentrification set in, many moved to the suburbs to escape the city’s noise and hecticness. I chose to stay, watching the neighborhood’s ups and downs.

Despite the changes, I have remained in Chicago. This city is my home. My friends, my memories, and my community are here. I thought about moving to Florida, where some cousins are, but my social network is here. Chicago has shaped me.

I trust my neighbors and count on their help. Once, I fell, landed on my back and couldn’t get up at 2:00 a.m. I was halfway out the door, and I yelled to my neighbors. They came out, picked me up, and brought me into the house. They fed me, cared for me and ensured I was okay. It’s nice to have neighbors like that.

I’m the last male in my family’s lineage, but their legacy lives on in this home in the stories, recipes and traditions they passed down.

For me, my family’s journey is not just about survival—it’s about thriving against all odds. We came here with nothing, faced hardships and built a life. That’s what being an immigrant is about. It’s about hope.

Fatema Hosseini is a Roy W. Howard Investigative Reporting fellow covering immigrant communities for Borderless Magazine. Send her an email at [email protected].