The Islamic Revolution ushered in a new normal for Iranian women. Some have fled, while others have built a life in the country despite the adversity.

N. K., 25, walked up to the gates of her university, bookbag in hand, and prepared for her classes at the Sharif University of Technology in Tehran. Like every other day, an administration officer stopped her, saying she could not be admitted.

The problem? Her hijab was too loose.

News that puts power under the spotlight and communities at the center.

Sign up for our free newsletter and get updates twice a week.

“I have so much work to do at the university,” N. K. said, recalling the repeated incidents months later. N. K. asked to use her initials out of fear of retaliation. “But today she says: ‘No. You cannot get [in]… because I don’t like your clothes. Because I’m not satisfied with the hijab you have.’” She thought, “I am supposed to be able to get to the university because I was qualified, but you are banning me from going through the door of the university. Who are you to do that?”

Iran’s Islamic Revolution shocked women who were accustomed to dressing, acting, and speaking how they wished. Before the Revolution, men and women dressed in bathing suits and swam together at beaches; they could host and attend parties together. Women could experiment with Western fashion like miniskirts and tight-fitting jeans. But the regime’s reign stripped these rights from women and imposed strict dress codes, establishing a new and unfamiliar way of life.

The following year, the government abolished coeducational schools, effectively separating girls and boys in schools and public spaces. These changes have had seismic effects on women, impacting all aspects of their lives.

“You cannot decide about your own body.”

For many women, these restrictions went beyond simply shaping how women dressed. It was, they say, an attempt to control their way of thinking — their minds.

“It’s not like they want to own our clothes and dress code,” N.K. said. “It’s like they want to own our minds. They want to own our life plans.”

Read More of Our Coverage

This civil unrest was worsened by the killing of 22-year-old Mahsa Amini by morality police in 2022 when they claimed her hijab was not being worn in accordance with government standards. Protests erupted across the country in support of the “Woman, Life, Freedom” movement. For some women, the further restrictions on their rights have driven them to flee the country.

N. K. left Iran for Copenhagen a few months ago amid a worsening political and economic state. She saw a lack of opportunity and a narrowing of her rights. There, she awaits the approval of her student visa to move to the United States, where she plans to pursue her doctorate degree in astronomy at the University of California Riverside. She believes Europe or the U.S. would be the best places to continue her education.

Thousands of miles from Iran, she reflects on how the Islamic Republic’s practices shaped her childhood.

For much of her life in academia, she’s faced misogynistic social practices at the hands of Iran’s current government, such as being barred from entering her university or feeling unsafe around the country’s police. She left the country in hopes of feeling more secure abroad, N. K. noted.

“Since you were very little and you go to the school, they are brainwashing you,” she said. “They want to keep telling you that you have done something wrong [for being a woman]. That you are wrong. You are guilty.”

N. K. said she was especially impacted by the policies that restricted Iranian women. She said she frequently argued with her university’s administration, who wouldn’t admit her into the university gates without fixing her hijab or some part of her clothing.

“You cannot decide about your own body,” she said. “You cannot decide about your own hair. You cannot decide if you want to wear something or not.”

Careers in STEM an equalizer for women

While several Iranian women described frequent misogynistic incidents, others of her generation had slightly different experiences studying in Iran.

Elnaz Nour, 32, moved from Iran to the United States four years ago. She is working as a Senior Clinical Research Coordinator at a Colorado university while studying for her medical board exams. “It was a suppressed society,” Nour said. “By nature, as a woman, you were oppressed and you weren’t able to even talk about your rights – the things you wanted to do.”

For Nour, she felt the separation between boys and girls from an early age stunted interpersonal relations. For those born after the ‘80s, these restrictions of co-education became normalized for generations of Iranian women.

Despite the significant rollback of women’s rights, some Iranian women say a career in the sciences has proven to be a step towards equality. Nour said she had never faced significant discrimination as a woman in an academic setting. While she was sometimes told that she was wearing too much makeup, or her clothes were too short, she maintained that Iranian women pursuing STEM subjects were typically respected.

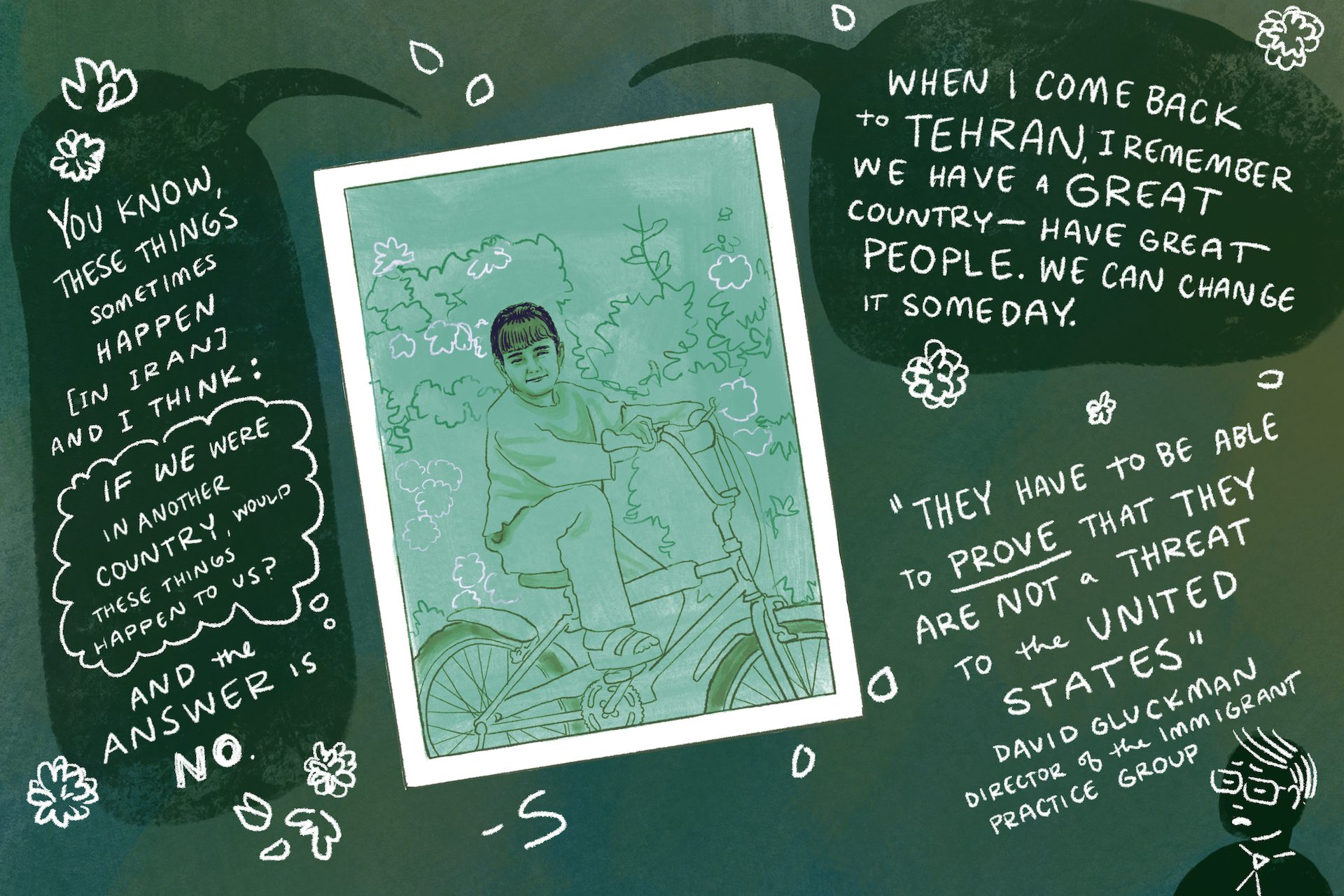

Similarly, S, who was granted anonymity as she awaits visa approval, noted that women in the industry are treated equal to men or even better in some respects. She said that while limitations on their clothing, nails or makeup often could restrict their access to university facilities, women are largely respected in academic settings when pursuing STEM fields.

“The amazing point is that science and jobs are the only two things in our country that women are treated better than men in relation to other countries,” S said.

In Iran, women make up 70% of graduates studying science, technology, engineering and mathematics, according to Quartz.

“You know the limitations that women have in my country, for their hijab and their clothing,” she said. “But this is not for science.”

Older generations witnessed restrictions sweep through the country

While younger women were raised under severe restrictions, Iranian women who grew up before the Islamic Revolution recall a memory of a different country where they experienced freedom that had long been stripped away. Some women fled after the Iranian Revolution to escape the oppressive restrictions imposed on women.

Farzaneh Shakib recalls seeing the wave of restrictions sweep across Iran, erasing freedoms that had been a way of life for women who came of age before the Islamic Revolution.

“[It was] ‘don’t wear this. Talk like this.’ For any movement, you should have some guardian,” Shakib said. “For example: traveling. If you were married, you had to have permission from your husband. If you were single, you had to have permission from a guardian.”

Shakib and her husband established an astronomy magazine, hoping to guide younger generations to the field in Iran. Nearly 30 years ago, the family moved to the U.S. so her husband could pursue a graduate degree. Leaving Iran also meant she could raise her future children in a space free from restrictions.

“I think we created something for her that we never had in Iran because we were 18 when the Revolution happened,” she said. “I’m happy we are here. It was so hard sometimes . . . But here, nothing is going to stop you from thinking big, shiny, colorful. I never had that chance over there.”

Read More of Our Coverage

Shakib noted being proud of the life she has created for their family. Since leaving, she has only returned three times. Her last visit was in 2012.

Sooti, who was granted anonymity to speak openly without retaliation, was born in Tehran in 1961. After attending school in Iran, she became a specialist in radiology and later a medical director at a private institute.

She recalled widespread instability that stunted social and economic advancements in science and technology following the revolution, in part, because of widespread sanctions.

“When I was a child growing up, the country was more stable and there was more improvement [in technology and science] than it is right now,” she recalled. The new Iranian government didn’t have an interest in “technological improvements, and also they didn’t show any good relations with the outside world – that’s how the country I am from has suffered.”

Some younger generations felt women bore the brunt of the government’s restrictions, while Sooti feels the government’s constraints impact men and women equally, as restrictions on alcohol, social gatherings and sometimes clothing still applied to both. Despite the widespread restrictions, she felt respected in her field. The government’s fear of advancement, she said, was what ultimately restricted her most in her field.

Decades later, women’s rights have continued to erode. Some women have learned to maneuver carefully around the restrictions, and remain hopeful that circumstances will change in Iran, while others seek a new life abroad.

Younger generations like Nour and N.K. have found themselves escaping Iran’s worsening conditions, while those like Shakib and Sooti look fondly on the country they once knew while embracing the home they built in spite of adversity.

“I just wish everything will get better for students and I wish it wasn’t like this,” Nour said. “I wish they could come here and pursue what they want to do and their dreams.”

UPDATE 1/14/25: A person’s name was changed to use only initials due to safety concerns.