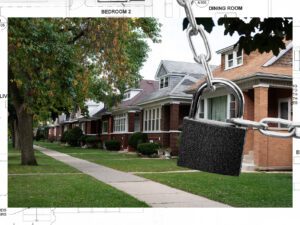

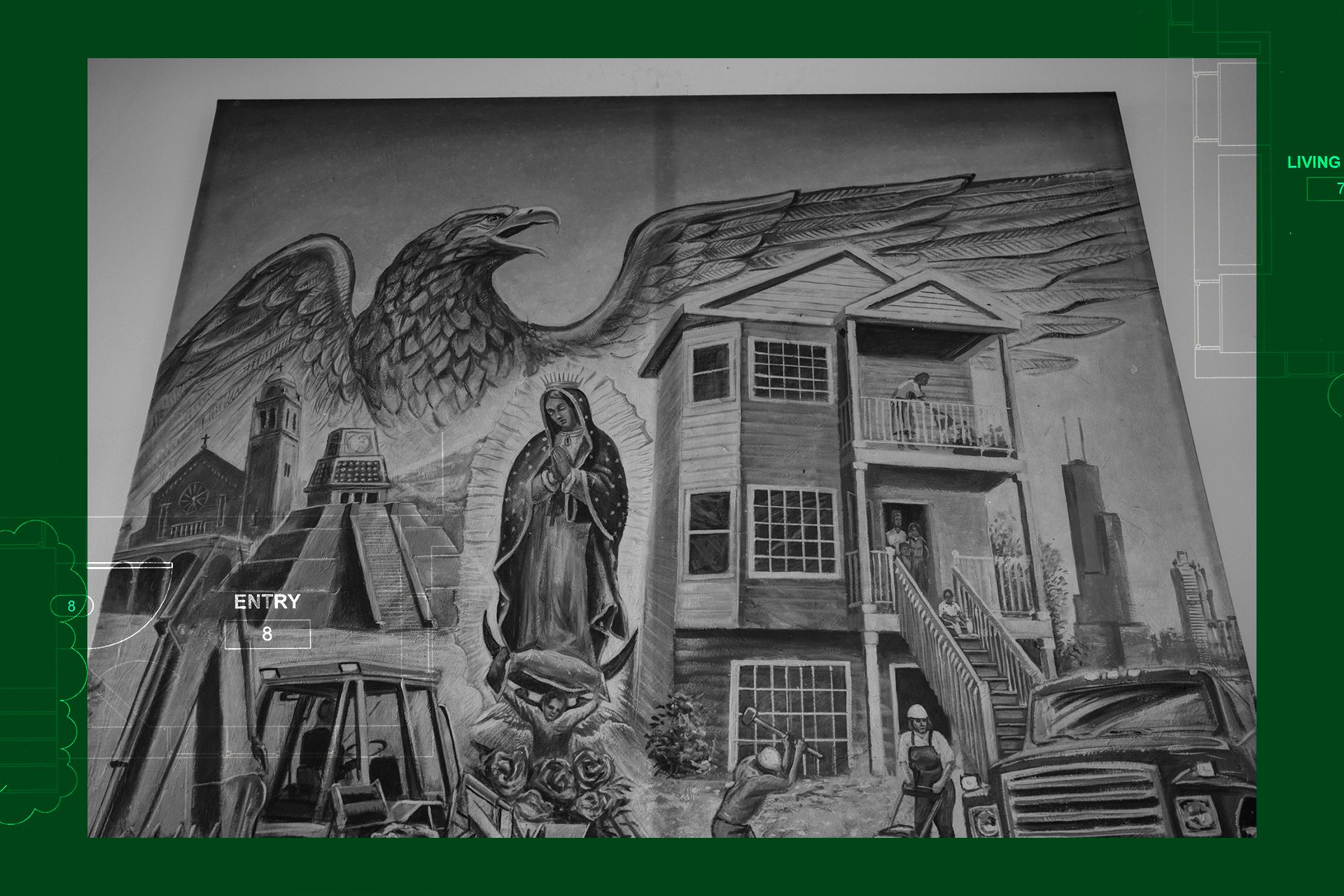

Photo illustration and photo by Max Herman/Borderless Magazine

Photo illustration and photo by Max Herman/Borderless MagazineAfter leaving Mexico with her family, Erika Ayala and her husband spent a decade working to buy a home. The Resurrection Project helped them navigate the challenges undocumented immigrants face to become homeowners.

Chicago became Erika Ayala’s home more than a decade ago. She left Mexico with her husband and young daughter in search of safety and a better future.

They lived in Guerrero, a Mexican state paralyzed by narcoterrorism and increasing violence. Residents of Guerrero became collateral damage amid government extortion, corruption and drug trafficking.

News that puts power under the spotlight and communities at the center.

Sign up for our free newsletter and get updates twice a week.

For Ayala, it wasn’t enough to leave the state to escape violence. Her family needed to leave the country.

Last summer, El Universal published a study revealing organized crime affects 81% of Mexico’s territory. There is an endemic of the disappeared, or desaparecidos from the ongoing cartel war. At least one hundred thousand people have been registered as missing as of 1964. This number is now increasing by 30,000 per year, according to la Comisión Nacional de Búsqueda de México — the National Search Commission (CNB).

Over the past 11 years, Ayala and her husband have worked to give their two daughters a better life by immersing them in the educational and extracurricular opportunities they didn’t have in Mexico. They wanted to give them stability and a foundation by putting a roof over their heads —one they could call their own.

Part of my goal was to own a home, but this wasn’t possible 11 years ago when banks rarely gave loans to noncitizens with ITIN numbers.

ITIN is an Individual Taxpayer Identification Number issued to non-U.S. citizens who are not eligible for a Social Security number to file a tax return.

It was nearly impossible to be considered for a loan. It was equally challenging to also pay the higher interest rate for individuals using an ITIN number and the full down payment amount. For undocumented families, banks require 20% of the property to be paid upfront. I had to put my goal of owning a house on hold.

Read More of Our Coverage

Since arriving in the city, we have moved four different times. We first lived with extended family but didn’t stay long because it was a confined space. We then moved in with another family and shared an apartment which wasn’t ideal either.

Years later, we were finally able to afford our own apartment. We have tried to live with family as long as we could, but there isn’t anything better than having your own place.

We want the freedom to make noise and arrive home when we please. Having privacy in our own home is especially important with two young daughters.

When COVID-19 hit in 2020, we thought it could finally be the right moment to buy a home. During the economic recession sparked by the pandemic, we expected housing prices to drop but prices soared instead. We thought the pandemic had once again put our dream on hold, but then we found the Resurrection Project. The community organization is where we found support in helping us navigate homeownership as undocumented immigrants.

I saw on the news the Resurrection Project was distributing grants to help families who weren’t eligible for COVID relief funds because of citizenship status. My husband and I had just lost our jobs and were struggling to stay afloat. I immediately applied for the relief and received a $1,000 check in the mail a week later. That check helped us tremendously, and I wanted to return some of what the city had given to me.

I researched the Resurrection Project and then called to see if I could volunteer with them during my newfound free time after losing my job. While working there, I met people in the home empowerment department and learned everything I needed about preparing to buy a home.

After learning about the process, we began gathering all the documents we needed. Thankfully, we were already relatively prepared.

Read More of Our Coverage

When we arrived from Mexico, we had a bit of savings for the down payment. We established two or three years of stable employment, and most importantly already had a credit history. My husband and I opened a credit card after arriving in the U.S.

I remember being hesitant because in Mexico the credit culture is very different, it isn’t a necessity. I had to get used to using it consistently, but it paid off years later when I reviewed my credit for the first time and saw I had a good score. I learned that building years of good credit is the largest barrier to owning a home for most families without citizenship. Most families that I know use a debit card if they have a bank account, and the rest keep their money in cash at home. Most people also don’t have an ITIN, and without that, all doors are closed.

We saved 20% before formally submitting a bid for a condo.

Last September, we signed a contract to buy a new condo from the Chicago Housing Trust. The construction is almost complete. This permanent home is especially important because we don’t have to unroot our lives by moving again.

Our eldest daughter will be able to attend the same middle school this school year and our youngest will begin kindergarten nearby. My husband will still have easy access to the train, which he takes downtown to work at a restaurant, and I will still be close to Pilsen and the Mexican Consulate to continue my volunteer work for the Resurrection Project.

We have fallen in love with the city and the life we built in Chicago. We found a place with opportunities for our daughters. Staying in my current neighborhood will limit the time I spend commuting. It will give me more time to spend taking my daughters to extracurricular activities and helping them with their homework. As a mother, one of my biggest goals is for my daughters to attend college.

After fleeing violence in Mexico and moving around for a decade, we will finally be able to own a home and establish roots in this city forever. I want this for my family, and for every other immigrant family, regardless of their citizenship status.

My entire family is happy we will soon be able to move into our home. We hope to live here for many years to come.

This content was made possible by a grant from The Chicago Community Trust.