Samantha Friend Cabrera for Borderless Magazine

Samantha Friend Cabrera for Borderless MagazineThe Chicago ICE Field Office conducted more than 13,000 searches of the LexisNexis database between March and September 2021.

On a sunny morning in June 2022, Claudia Marchan sat down at her desk in her Harwood Heights home with a cup of coffee. Before starting her work day, she checked her personal email and saw a message with the subject line “Report.” Earlier that week, she had discovered that her information was in an online database, and she had requested a copy of what was included, fearful that this information could be used against her or those close to her. She opened the email and was shocked to find a 46-page document detailing the personal information the data broker LexisNexis had on her and the people around her.

Want to receive stories like this in your inbox every week?

Sign up for our free newsletter.

“When you hear about these things, part of you thinks ‘does this particularly impact me or my family?’ and you want to think that it doesn’t,” said Marchan, who leads the nonprofit Northern Illinois Justice for our Neighbors, an immigration rights advocacy group, and is an active member of the Illinois Coalition for Immigrant and Refugee Rights.

Marchan spent much of her life living in the U.S. without documentation. She was protected under the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals program and obtained lawful permanent residence in 2021, but still felt uneasy about her information being used against those close to her. “It was hard for me and it was the first time that I was actually scared,” she said.

Marchan is among the Chicago-area individuals, organizations and advocates for immigrant rights suing the research and data brokerage firm LexisNexis over its collection and sale of the personal data of immigrants in a $22.1 million contract with U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement. The lawsuit states that this data — which includes names, addresses, court records and even previous romantic partners — will unlawfully aid ICE in warrantless surveillance of immigrants. But nearly anyone with an online presence can be found in the LexisNexis database, which includes the consumer information for 276 million people in the U.S.

Marchan’s LexisNexis report included addresses, emails and phone numbers to reach her and those associated with her. It also included her Social Security number with no redactions. As she read through the lengthy document, she began thinking about all the interactions that had contributed to it. She thought about the bills she had once been so proud to be able to put in her name and how simple necessities like electricity had contributed to this massive profile.

“The most shocking thing to me is how they managed to capture every single person at different walks of life, at the different addresses that I was at throughout my whole life, and I don’t think that they’ve missed an address,” said Marchan. “It was very precise, very complete, and very detailed.”

Six Months and One Million Searches

ICE conducted over 1.2 million searches of the LexisNexis database between March 2021 and September 2021. More than 13,000 of these searches were conducted by the local Chicago ICE Field Office, according to records obtained by Just Futures Law, a nonprofit organization offering legal support and advocacy to communities that are subject to mass surveillance, incarceration and deportation.

“We were anticipating that the scale would be large, just because of how much information they can get from using a tool like Accurint, but we were actually really shocked by the sheer number of searches conducted and the magnitude,” said Dinesh McCoy, staff attorney at Just Futures Law.

LexisNexis sells this data through a platform it calls “Accurint” which provides a searchable encyclopedic summary of an individual’s public and non-public information to law enforcement officials.

Read More of Our Coverage

The plaintiffs on the case, including Mijente, Organized Communities Against Deportations (OCAD), Just Futures Law and three individuals, claim that the collection and sale of personal data is a violation of the Illinois’ Consumer Fraud and Deceptive Business Practices Act and puts immigrants at risk of warrantless monitoring and subsequent unjust incarceration and deportation, going against Illinois’ Sanctuary City policies.

“It’s happening without a warrant, without notification, without a way to know how you can scrub your information,” said Cinthya Rodriguez, a national organizer for Mijente, a Latinx and Chicanx nonprofit organization seeking racial, economic, gender and climate justice for their community.

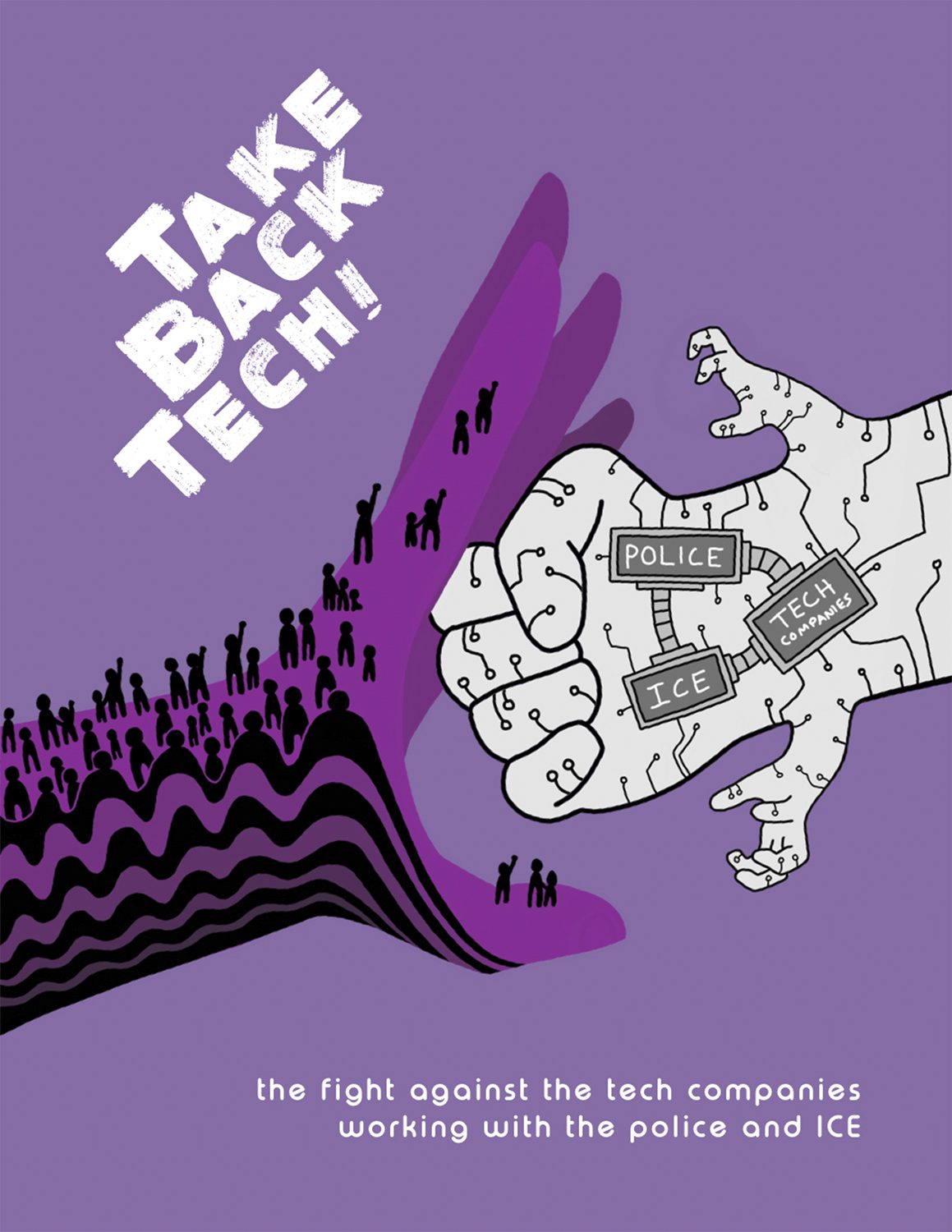

She works on the #NoTechForICE campaign, an initiative aimed at spreading awareness and ultimately putting a stop to the collaboration of tech companies with ICE for the means of surveillance, incarceration and deportation.

The lawsuit gives examples of how ICE has used this data to surveil individuals without warrants. The list includes determining immigration status, identifying a home address or current location to conduct raids and arrests, and learning about immigrants’ families and those associated with them.

“It’s happening without a warrant, without notification, without a way to know how you can scrub your information,” said Cinthya Rodriguez, a national organizer for Mijente, a Latinx and Chicanx nonprofit organization seeking racial, economic, gender and climate justice for their community.

The lawsuit also details the contract between ICE and LexisNexis, including a requirement that ICE have access to “track daily address changes and credit activities of targeted persons” by providing access to daily updates from sources including insurance, phone, employment, utilities, renter information, licenses and credit checks.

“On a collective level, all of that information becomes a tool at the disposal of ICE to have a one stop shop to look up the information that’s necessary to surveil somebody and access their information,” said Rodriguez.

A representative from LexisNexis said that the contract with the Department of Homeland Security complies with the policies set in President Biden’s Executive Order 13993. “These policies emphasize a respect for human rights, and focus on threats to national security, public safety, and security at the border,” said Jennifer Grigas Richman, the director of external communications at LexisNexis. “LexisNexis Risk Solutions supports the responsible use of data in accordance with governing statutes, regulations and industry best practices. As with our other customers, the Department of Homeland Security must use our services in compliance with these principles.”

Subverting Sanctuary Cities

Just Futures Law states that ICE’s use of the LexisNexis database allows law enforcement to skirt around local policies in sanctuary cities. For example, ICE has access to real-time incarceration information through LexisNexis, allowing ICE to use LexisNexis as a backdoor to circumvent local laws and policies that would otherwise protect such information. ICE is then able to identify and arrest immigrants as they are released from jail, a violation of Illinois law according to Cook County’s ICE Detainer Ordinance.

Along with violating Illinois established privacy and consumer protection rights included in the Illinois TRUST Act, Cook County’s ICE Detainer Ordinance and Chicago’s Welcoming City Ordinance, opponents are concerned that the LexisNexis database removes the typical due process protocols like filing a subpoena or court order to access personal information.

“We are seeing data being collected without our permission to be used to make general analysis and stereotypes about our communities and those who live there,” said Antonio Gutierez, cofounder and the Strategic Coordinator for OCAD, a nonprofit organization fighting against the deportation and criminalization of immigrants and people of color in Chicago and surrounding areas.

“When we talk about a number like 1.2 million searches, in one person’s report, the search often will return dozens of names and addresses of people that are also affiliated with them,” said McCoy. “So we’re talking not about just individuals, but about whole communities that surround them.”

Organizations like OCAD have spent years advocating to stop this type of data exchange to prevent amplifying the distrust that the immigrant community often feels toward law enforcement.

“We want to hold agencies like ICE and LexisNexis accountable for the damage that they’re creating in our communities,” said Gutierez.

McCoy added that while these searches are specific to who an ICE agent is investigating, data on those who are affiliated with the target individual — like friends, relatives, roommates and coworkers — can also show up.

“When we talk about a number like 1.2 million searches, in one person’s report, the search often will return dozens of names and addresses of people that are also affiliated with them,” said McCoy. “So we’re talking not about just individuals, but about whole communities that surround them.”

The Big Picture

This issue is specifically dangerous for immigrants and communities of color that are disproportionately impacted by unwanted surveillance. But LexisNexis has the ability to access, collect and sell the personal information of essentially anyone with a digital footprint without their consent, or in many cases, knowledge.

“It’s not just immigrants that are being placed in this database,” said Gutierez. “This database is actually capturing and centralizing information from millions of Americans and it’s being shared, not only with agencies like ICE, but it’s also unspecified what other agencies have access to this database.”

LexisNexis’ website claims to have over 276 million U.S. consumer identities. The 2020 U.S. Census Bureau counted 258.3 million adults over 18 that reside in the U.S.

“We should more broadly look at this through the lens of not just immigration, but also racial justice and surveillance capitalism and topics that are bigger than just the immigrant rights context,” said McCoy. “This is affecting people in all different contexts, but has specific problems for marginalized communities — and primarily Black communities — who face more criminalization and more targeting from these technologies.”

OCAD has been involved in similar campaigns in the past, including one against the city of Chicago regarding the Chicago Police Department’s creation of gang databases. Gutierez says these types of databases violate citizens’ due process rights by not allowing individuals to know that they’ve been placed in a database, and they don’t provide a clear pathway to contest the information or get information extracted from the database’s files.

“This is affecting people in all different contexts, but has specific problems for marginalized communities — and primarily Black communities — who face more criminalization and more targeting from these technologies,” McCoy said.

“There’s a lot more data to draw inferences about people in the world that would not have been possible 30 years ago, and that possibility creates a whole series of problems,” Aziz Huq, a University of Chicago law professor who specializes in technology and law, told Borderless. “There are all sorts of ways in which this new kind of information technology can be employed, either by private parties, or by the state, and sometimes it helps people and it’s generally a good thing. And sometimes the technology is used for purposes that you or I might think are unjust or immoral — but the technology is out there and it doesn’t go away once it’s out there.”

Issues with who can access data, and subsequently sell it, have been a prevalent discussion. Companies like Google, Facebook, Amazon and TikTok are among those that have been sued for data privacy violations in recent years, and this specific type of “surveillance capitalism” is not new, either.

Previously, Thomson Reuters, a media conglomerate out of Canada, was under fire for selling their database of sensitive personal information about immigrants to ICE. In April of 2022, the company vowed to reevaluate their contracts with the agency after the British Columbia General Employees’ Union — a Thomson Reuters share holder — used its stake in the organization to push for the company’s analysis of the human rights risks associated with their several-million-dollar contract with ICE.

As of 2021, LexisNexis is the primary provider of these law enforcement database services to ICE.

“We’re stuck in a situation where technology is changing, where private and state actors are acquiring and using technology basically because it’s unregulated. And we don’t have a political system that can respond to changes in anything like a timely fashion,” said Huq. “We’re just going to end up behind the curve, and sometimes that’s going to benefit private companies, and private companies are going to be able to do stuff they probably shouldn’t be able to do.”

Fight For Peace of Mind

Since receiving her LexisNexis profile, Marchan says she has lost sleep and suffered from anxiety. She is worried how this data could affect those that she’s closest to, especially family members who are undocumented or don’t have U.S. citizenship.

“Just looking at my family as a whole, there are still folks that are undocumented, and that can very well be affected by this,” said Marchan. “The fear is right, the loved ones that are still at risk still don’t have permanent protections.”

At her job, she often gets questions from immigrants who are nervous about providing their data to companies, even when it’s essential in order to build credit or purchase utilities. She understands their hesitation and frustration, and she hopes this lawsuit will put an end to the collection and sale of personal data without consent.

Gutierez says that OCAD also hopes to further the conversation around how major corporations like LexisNexis can be held accountable.

“The lawsuit allows the opportunity for us to really start a dialogue around how data is being used to criminalize not only immigrant communities, but overall communities of color in this new era,” Gutierez said.

Along with restitutions and fines for damages and unfair business practices, the plaintiffs also want to better understand how these tech companies are being regulated by the state, and how the community can make sure they’re not profiting off of individual personal data to an extent that violates the privacy rights of the individual. They want more transparency on how they inform the public about their processes and around how to contest the information that they collect.

Other jurisdictions, like Europe, Canada, and China, deal with data very differently and have created laws that protect individuals over corporations, but America has no such federal laws, and it’s left up to state legislation to enforce protections.

Gutierez says they want to restore peace of mind to the immigrant community “that their information won’t be exchanged for the purpose of profiting in order to then detain, deport or displace the individuals in our community.”

McCoy is concerned over the chilling effect the collection and sale of this type of data may have.

“These types of everyday transactions and things that are really necessary to survive shouldn’t be the source of police and the government constantly keeping track of your every move,” said McCoy. He hopes this lawsuit will be the start of a broader conversation around illegal data practices.

Though the lawsuit is specific to Illinois, the advocacy groups hope the conversation will spread across the U.S. and create more awareness and action from other groups around the country.

“Continuing to put pressure on the company is really important, but Cook County is just the beginning,” said Rodriguez.

Check out our FAQ for answers to common questions about data security and the sale of personal information.

Correction 3/2/23: An earlier version of this article incorrectly stated that the Trump administration’s challenge of DACA was a factor at the time that Claudia Marchan sought her LexisNexis report. While the issue was a concern, the two occurred at separate times.

Correction 3/3/23: This article has been updated to reflect that Claudia Marchan obtained legal permanent residence in 2021.

Bring power to immigrant voices!

Our work is made possible thanks to donations from people like you. Support high-quality reporting by making a tax-deductible donation today.