Jonathan Aguilar/Borderless Magazine

Jonathan Aguilar/Borderless MagazineA local factory was once the largest producer of thorium in the world. This fall, the “radioactive capital of the Midwest” is doing one last cleanup.

Sandra Arzola was relaxing in her West Chicago home one weekend in 1995, when she heard a knock at the door. Recently married, she shared the gray duplex with her husband, mom and sister, and family members were constantly coming and going. But when Sandra answered the door that day, what she learned would change how she looked at her home and suburban community forever.

At the door was a woman representing Envirocon, an environmental cleanup company. There was thorium on the family’s property, the woman said, and if it was OK with them, workers were coming to remove it. It was the first time Sandra had heard of thorium.

News that puts power under the spotlight and communities at the center.

Sign up for our free newsletter and get updates twice a week.

“It took me by left field,” she said. “But [the representative] made it sound like everything was going to be fine.”

Unknowingly, the Arzolas had bought their way into what the Chicago Tribune in 1979 called “the radioactive capital of the Midwest.” Not long after they purchased the property, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency designated it a Superfund site because of the hazardous waste in their yard.

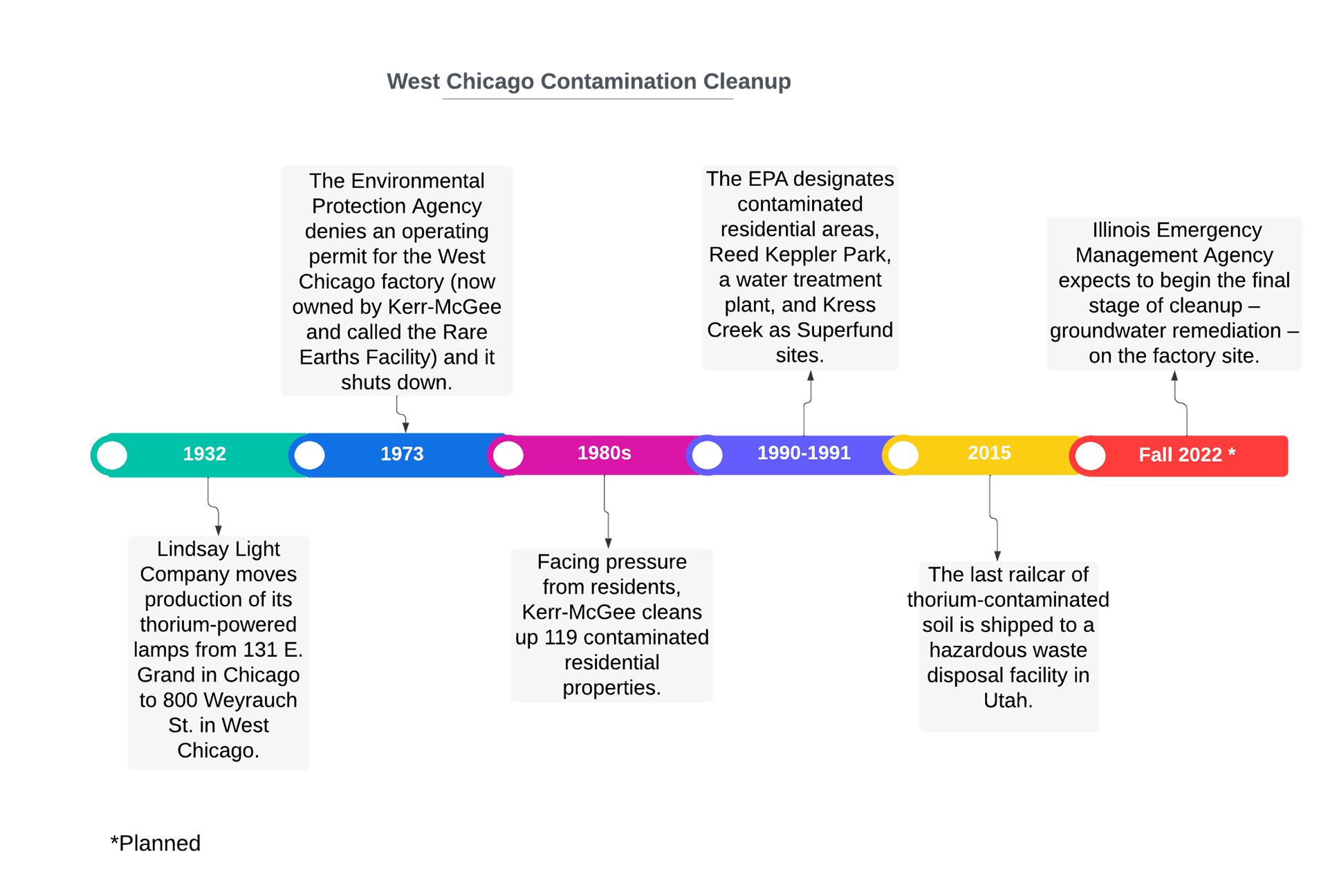

The source of the danger was the old factory one block to the south of the Arzola home, which Jesse Arzola frequently went past while walking their dogs. From 1932 to 1973, the factory was the largest producer of rare earth and radioactive thorium compounds in the world. It started out producing lamps and later supplied thorium for the federal government’s atomic bomb development. But perhaps the factory’s most lasting legacy, at least in West Chicago, is the harmful radioactive waste that was dumped in ponds, piled at the factory and buried around homes and sidewalks across town.

Residents raised health concerns as early as the 1940s about the toxic material, but these were regularly dismissed by the factory, last owned by the Kerr-McGee Chemical Corporation. Comprehensive environmental protection rules weren’t put in place until the early 1970s, leaving the factory largely free to dispose of its nuclear waste for decades.

It has taken just as long for the company and government to clean up the radioactive waste. As of 2015, the radioactive sites under federal jurisdiction near the factory have been cleaned to EPA standards. There are no remaining health risks from the land, according to government officials.

But below the factory, the groundwater is still polluted with a range of toxins – particularly uranium – that exceed protection standards. The Illinois Emergency Management Agency, which has jurisdiction over the site, expects remediation to begin this fall. Although people in the area don’t use that polluted groundwater, the state says it’s the last known contamination issue – and removing most of it will hopefully eliminate any lingering concerns for residents.

While city officials and some residents are eager to erase the stigma of nuclear contamination from the town’s image, many newer residents, including myself, are just now learning about their neighborhood’s long thorium history.

“People don’t want to discuss it,” said Jesse Arzola, “because they are afraid of the unknown.”

The Arzolas were part of a wave of new residents who moved into the suburb 30 miles west of Chicago starting in the 1980s. From 1980 to 2007, white residents in the factory area declined by two-thirds and Hispanic residents nearly doubled, according to an analysis by the Daily Herald. Many new West Chicago residents, especially those who did not speak English, didn’t know of the radiation danger when they moved in.

Prolonged or high levels of radiation exposure can damage genetic material in cells and cause cancer and other diseases later on, especially for children, who are more sensitive to radiation. Only two public health studies, published in the early 1990s, have been conducted in West Chicago. Both found elevated cancer rates in the 60185 zip code, which includes the neighborhood around the factory.

Today, many residents still suspect that their cancers and other debilitating illnesses are related to factory contamination. Language barriers and discrimination add to the mistrust for many Latino residents.

And decades of secrecy around the factory have left a legacy of worries.

When Sandra Arzola first toured their home in 1990 with her mother and sister, she saw signs in the windows of neighboring houses with a big “Th” circled and crossed out.

“What’s all that about?” she asked.

“Oh, I don’t know,” the realtor replied.

Sandra Arzola wishes she had been told the truth when she was looking for a home. Decades later, she and her husband are living in another home in the same neighborhood. She still doesn’t trust official statements that their property and the city drinking water are safe. They use bottled water instead of tap water to cook and drink because of their concerns.

“If the realtor had been more forthright initially, then I could tell her, ‘It doesn’t matter’ or ‘Show me something else,’” Sandra Arzola said. “But she wasn’t honest.”

Decades of Unregulated Dumping

The challenges facing West Chicago residents today began 90 years ago, when Charles R. Lindsay moved his lamp factory from Chicago to what was then an undeveloped little town with multiple rail connections. The factory, now officially known as the Rare Earths Facility, took monazite ore and used powerful acids to extract minerals to make gas lanterns, which burned thorium nitrate to emit an incandescent glow. During World War II, it also supplied thorium to the federal government to develop the atomic bombs that were later dropped on Nagasaki and Hiroshima, Japan.

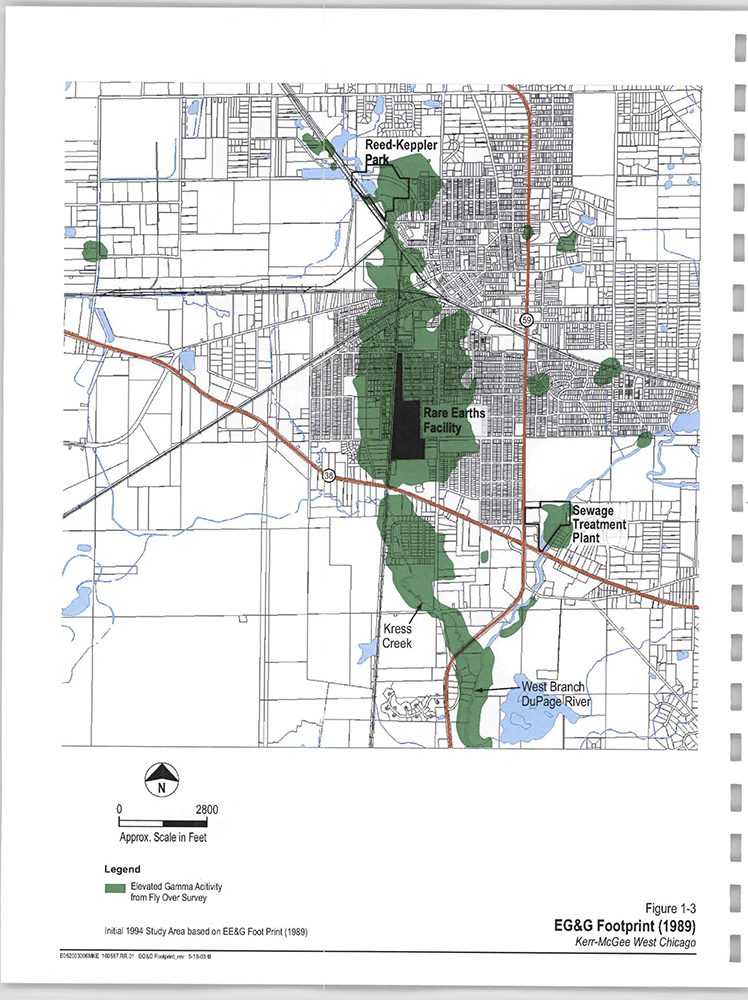

During its four decades of operation, the Rare Earths Facility processed up to 141,000 tons of monazite. The liquid waste from the extraction process was dumped into unlined ponds around the factory, seeping into the surrounding water table. Solid waste, a black, sand-like material known as thorium tailings, piled up on site. Old-timers share stories of sneaking into the factory grounds and playing on “Mount Thorium.” When the pile got too big, the waste was trucked down the road to a new pile in Reed Keppler Park.

Facing mounting piles of toxic waste, Lindsay came up with another solution: offer the waste to residents for landscaping. From the 1930s through the 1950s, radioactive thorium tailings were distributed across town, mixed with concrete to pour foundations, mixed with topsoil for gardens and spilled along roadways. The company continued to do this as the risks of radiation exposure became widely known starting in the late 1940s through its effects on Japanese atomic bomb survivors.

Soon after the factory moved to West Chicago, people started complaining. In 1941, nearby residents sued Lindsay Light for releasing airborne hydrofluoric acid that killed trees and shrubs nearby.

The federal government did not begin regulating nuclear materials until 1954. Starting in 1957 the company received repeated citations for safety violations, including failing to fence off radioactive storage areas, exposing workers to radiation levels above standards and improper waste disposal.

As the environmental movement gained steam through the 1960s, growing public pressure pushed Congress to create the Environmental Protection Agency and pass the Clean Air Act of 1970 and Clean Water Act of 1972. That resulted in sweeping new regulations – and obligations to the American public – for companies like Kerr-McGee, which had gotten used to operating with limited oversight.

Internal memos from the time show company executives scrambling to respond.

“This visitation is the forerunner of many future visits and closer surveillance and we must learn to stay one step ahead,” wrote O.L. Daigle, a plant manager for the Rare Earths Facility, in a 1972 memo about an upcoming EPA visit.

By the next year, Kerr-McGee had not complied with a broad slate of new environmental safety regulations. The EPA denied the company’s request for an operating permit and the factory shuttered in 1973. It was cheaper to cease operations than follow the new rules.

By 1980, Kerr-McGee had started the process of closing down the West Chicago facility for good. Pressure from residents and the city pushed the company to begin cleanup on 119 contaminated residential properties.

Still, Kerr-McGee had another plan that worried residents: to permanently store 13 million cubic feet of radioactive waste at the factory site in a four-story, 27-acre clay-covered cell. Concerned residents formed an organization, the Thorium Action Group, to fight the company’s proposal. This spawned more than a decade of legal battles between residents, the city of West Chicago, and state of Illinois — who wanted the thorium out of town — and the company and the federal Nuclear Regulatory Commission, who insisted the waste could safely be stored in this densely populated neighborhood of West Chicago.

After the state of Illinois took over oversight of the factory waste, the dispute finally appeared close to a resolution. In 1991, state lawmakers passed a bill that would charge the company $130 million each year to store the waste on site. Rather than pay the bill, Kerr-McGee decided to ship the contaminated materials to a hazardous waste disposal site in Utah.

Many New Residents Were in the Dark

Moving the thorium waste out of town would take over two decades to complete. In the meantime, there was still the problem of radioactive tailings embedded around the neighborhood.

The EPA did a series of flyover scans, street-by-street surveys and other testing to assess the damage. By 1991, contaminated residential properties – the final count was 676 out of 2,174 surveyed – as well as Reed Keppler Park, a wastewater treatment plant and Kress Creek south of the factory were placed on the EPA’s National Priorities List as Superfund sites. The wastewater treatment plant’s contamination came from receiving thorium tailings as fill during construction, not because of polluted sewage, according to the EPA.

The Arzola family’s home was among these sites. After the Envirocon visit, cleanup got underway. Workers in white hazmat suits excavated soil up to eight feet deep around the property. “The only thing left intact was the house,”Jesse Arzola said. “They dug right up to the foundation.”

The cleanup crew also tore up the sidewalk. To get to their front door, the family, including the couple’s two-year-old daughter, crossed four-foot wide wooden planks over the gaping hole in the ground. They didn’t trust the sturdiness of the guardrails, and instead walked carefully along the center. After the digging, the area was backfilled with clean dirt. The entire process took over six months.

The Arzolas’ experience is far from rare. Realtors in West Chicago have operated with a “don’t ask, don’t tell” policy, said longtime realtor and former West Chicago resident Dan Czuba. Unlike for radon or lead, realtors never received directives from the state or any licensing board to disclose other harmful thorium byproducts.

People have had to do their own homework and decide whether or not a home was a risk. “To this day,” Czuba said, “I still don’t know that there was an official statement of, ‘Thorium will hurt you.’”

Latino residents also continued moving in during the decades following the factory’s closure. “The Mexican community wanted home ownership,” said Czuba. “They took the slop and the junk from the non-Hispanics. They didn’t argue and complain, they fixed them up.”

By 2010, West Chicago became the only town in DuPage County with a majority-Latino population. Today, 55% of its over 25,000 residents speak a language other than English at home, and 32% are foreign-born. Activists feel that many of the newer residents weren’t fully informed, or informed at all, about the risks of living near the former factory.

“There was a lot of white flight, which brought in Mexican families who didn’t know [the history], and in many cases didn’t even speak the language to know,” said Cristobal Cavazos, a local immigrant rights activist with Immigrant Solidarity DuPage.

Throughout the decades, various groups have tried to get the word out about thorium. The Thorium Action Group was active through the early 2000s. Once the EPA got involved and Kerr-McGee agreed to move the waste out, the group dissipated. “We all felt for the most part that the message was heard and it was getting done,” said Czuba, the only realtor in the group.

”“To this day,” Czuba said, “I still don’t know that there was an official statement of, ‘Thorium will hurt you.’”

Czuba notes that no Latino residents were involved in the group, though West Chicago’s population was already about 17 percent Hispanic by 1980.

Anna Maria Escamilla Jacobo is a former West Chicago resident whose grandfather, Viviano Escamilla, worked at the factory starting in the 1950s. Jacobo said residents like her grandfather knew of the risks but were afraid to speak up for fear of discrimination.

“The mentality was, ‘nobody is going to listen to us because we’re Mexican. We can try, but it’s not going to do us any good,’” said Jacobo. “My grandfather feared that if he did say something there would be repercussions for him and the family and the Hispanic community. He would say, ‘Nothing you can do, nothing you can do,’ which was really sad.”

In 2007, Kathy Reinke-Bentham started another community group because none of her neighbors knew about the issue. She had watched the property next door get dug up for thorium and then change ownership. The next owner, Maria Salazar, had no idea. Reinke-Bentham got Salazar’s help translating information into Spanish and went around the neighborhood passing out leaflets and inviting people to meetings.

Today, residents continue to spread the word about the town’s thorium legacy and newer environmental issues. Cavazos’s group, which started in 2007, is among those mobilizing residents against a proposed waste transfer station in West Chicago. Members of Immigrant Solidarity DuPage see the station, which would be the city’s second, as yet another instance of environmental health hazards unfairly impacting this minority community.

Read More of Our Coverage

The factory’s toxic legacy in West Chicago also continues to impact residents. Although the EPA announced that residential property cleanup finished in 2003, the agency later found 13 properties that were not cleaned to its standards and needed further cleanup.

The agency also said letters were sent out to homeowners once their properties were remediated. The Arzolas don’t recall receiving one. City, state and federal officials also decided against instituting deed notices or restrictions disclosing the contamination, to ensure properties didn’t have their reputations unfairly tainted, according to the Daily Herald. Any information buyers might receive about past radiation scans or remediation now depends on a sellers’ willingness to pass it on.

The lack of easily accessible information surrounding the contamination and cleanups has left some residents with the nagging worry that there may be other hidden pockets of radiation around town. Some are afraid to plant edible gardens. The Arzolas want an updated scan of the area. Many have heard enough talk of thorium to cause concern, but not enough detail to feel confident that their environment is safe.

“Is It Because of the Thorium?”

One house to the west and across the railroad from the Arzolas, Erika Bartlett grew up playing along the tracks and under her yard’s sprawling old oak trees. When she was diagnosed with leukemia in 2012, at age 34, a friend asked if there was anything she could have been exposed to.

“Wait a minute, I actually was,” Bartlett told her friend. She thought back to her high school years, when the oak trees, swingset and above-ground pool at her house were removed during the radiation remediation. Bartlett realized she had spent her childhood, starting from age four, in a neighborhood embedded with nuclear waste.

She wondered how many others living near the factory had similar health problems. That started her on a yearslong personal investigation into the town’s thorium legacy.

Between 2012 and 2016, as Bartlett was undergoing cancer treatment, she knocked on doors in the neighborhoods around the factory, an area covering about one square mile. She found over 200 cases of cancers and other illnesses that could stem from radiation exposure, including birth defects, Hashimoto’s and aplastic anemia, the illness that killed the pioneering radioactivity researcher Marie Curie in 1934.

“When I first started, I didn’t think I’d find anything,” Bartlett said. “But block after block, it seemed like a bigger deal than I thought.”

The EPA estimated that, before the waste was removed, radiation levels in some residential neighborhoods in West Chicago increased lifetime cancer risks up to 70 times what is acceptable. This means that if 10,000 people lived in those maximum exposure areas, 70 of them would develop cancer, in addition to the risk that 1 in 3 Americans will develop cancer in their lifetime. That doesn’t account for other possible health effects such as thyroid and autoimmune diseases.

The only official health studies into the impacts on people living near the factory were conducted over three decades ago, by the Illinois Department of Public Health. Among residents in the 60185 zip code, studies in 1990 and 1991 found elevated rates of cancer, including melanomas and lung, colorectal and breast cancers. By grouping exposed and unexposed people together, however, researchers said more differences may have been masked.

By 2006, follow-up assessments by IDPH concluded that the four Superfund sites posed “no apparent public health hazard.” That doesn’t mean that residents aren’t living with ongoing health impacts. A 1994 report notes that “because of the long latent period for most cancers, current cases do not reflect recent exposure.” Today, people may still be experiencing health issues from exposure decades earlier.

In Facebook groups, West Chicago residents sometimes compare notes about their health issues. Anna Maria Escamilla Jacobo saw one of these threads in 2014. Comment after comment, she read about neighbors with lung diseases, early onset cancer and autoimmune disorders.

“Heck yeah,” she thought, “this is me all over the place.” It was the first time she realized that her own illnesses might stem from living near the Kerr-McGee factory.

Jacobo and her sister, Ester Escamilla Hughes, grew up in a little starter home just west of the factory, across the street from Pioneer Park.

In 1989, just as Ester graduated high school, an EPA flyover survey found the area around the factory, including the park and the sisters’ daily route to school, gave off elevated levels of gamma radiation. In some areas, the radiation was up to 40 times the average of what a person might ordinarily encounter.

It has taken the Escamilla sisters years to unravel the potential impact of living by the factory.

They both moved out of their childhood home by 1995. The next year, at age 27, Jacobo was diagnosed with Hashimoto’s, an autoimmune condition that affects the thyroid glands. The thyroid is one of the organs at greatest risk of damage after radiation exposure, especially in children. Jacobo also developed rheumatoid arthritis at age 44.

“The rheumatologist told me my lab results and X-rays were that of an 80-year-old with rheumatoid arthritis,” Jacobo said.

Her sister was diagnosed with a range of illnesses shortly after turning 40, including Hashimoto’s, rheumatoid arthritis and other conditions affecting her lungs and immune system.

“I started getting rashes, then I started gaining a lot of weight, my hands hurt, my fingers were turning purple,” Hughes said. “I was like, ‘What is happening to me?’”

Today, longitudinal studies are difficult. Some who were exposed for decades have since moved away, while others arrived during or after the cleanup.

Jesse and Sandra Arzola have had prostate and thyroid cancer, respectively. Before they talked with me they didn’t connect their illnesses to past radiation exposure. It’s hard — impossible really — to tell if any resident’s illness stems from living near the factory, exposure to other carcinogens, genetic predisposition, or all of the above.

But each new ailment comes under heightened scrutiny as residents ask, “Is it because of the thorium?” The community will never have a definite answer, even as they are haunted by ongoing worries.

Yet others, like West Chicago Mayor Ruben Pineda, spent their entire lives living near the factory — Pineda even played at the Reed Keppler dump site — and seem perfectly fine. “I’m not aware of anybody who was ill from the factory,” Pineda said. He added that if there were cases, the information would be privileged to clients and attorneys involved in lawsuits.

Dozens of lawsuits have been filed against the factory for damages to health and property. A few — those with political clout or connections, notes the realtor Czuba — won hefty individual settlements. In 1998, a significant legal win came for hundreds of families when a district judge ordered Kerr-McGee to pay $5 million for “medical monitoring” to account for future health effects on children living near the factory.

Bartlett’s family was part of the suit. She and her sister each received $4,000 and in return agreed not to sue the company for future personal injury. “The lawyer said, ‘Take it. If you get sick there’s nothing you’re going to prove, they have such good lawyers,’” Bartlett said.

Bartlett’s leukemia came back in 2014. Newer, effective treatments have allowed her to live in remission, but have left her with brain fog, vision impairments and cognitive issues.

The settlement money “doesn’t go far,” she said. “It does nothing when you’re sick.”

Not Quite “Past History”

In November 2015, the last rail car of thorium-contaminated soil trundled away from West Chicago to a hazardous waste dump in the Utah desert. Mayor Pineda declared it a “watershed moment.” Cleanup had stalled for years after Tronox, Kerr-McGee’s spinoff company, went bankrupt in 2009.

Today, the Rare Earths Facility is owned by a government trust that channels federal monies into the remaining cleanup.

In the mayor’s view, the disaster is now “past history.” He’s proud of the activists that got people in power to listen. Cleanup is almost done. And now he’s ready to talk about other things.

“I don’t want that word [thorium] to pop up every time you hear ‘West Chicago,’” Pineda said.

That history will come back to life this fall, however, when the Illinois Emergency Management Agency begins the last phase of remediation on the factory site.

The extensive groundwater contamination under the factory is currently contained by sheet piling that goes 70 feet below the ground, which was initially put in place to protect workers excavating contaminated soil. It now traps residual contaminants, preventing the groundwater from naturally diluting them over time.

Read More of Our Coverage

A network of 122 monitoring wells on and around the site show several contaminants, notably radioactive uranium, exceed state standards. As a result, nearby residents aren’t allowed to drill new wells.

“As long as humans are not consuming the groundwater, there is no true health hazard,” said Kelly Horn, IEMA’s Branch Chief of Radiation Protection Services.

The agency will use almost all of the remaining $36 million in federal funds for the operation, which will take three to five years.

IEMA will release an environmental analysis of the cleanup project this summer, which Horn expects will show no negative impact on residents.

“Because the soil has been remediated, and the groundwater remediation will produce minimal waste, there really is no human health risk,” said Horn.

The city of West Chicago plans to build a park designed with community input on the old factory site once remediation is complete. “While the history will always be there,” said City Administrator Michael Guttman, “hopefully something pretty stupendous will be in its place.”

I asked Guttman if the city has considered putting up signs noting the site’s history. Victims of the atomic bomb fallout in Nagasaki and Hiroshima are memorialized with peace parks. Some residents want to see a tribute to the people affected by the Rare Earths Facility, which supplied materials for those bombs.

“I have not given that a moment’s thought yet,” Guttman said.

“Maybe that’s something the community will have input on?” I asked.

After a few moments of silence on the other end of the call, I moved on.

“It’s Still Happening”

On the one hand, the story of West Chicago and thorium is one of triumph: a small town overcomes the odds and makes a big corporation clean up its radioactive waste. On the other hand, thorium still haunts some residents, especially those living with illness or deaths in the family that they suspect are related.

While cleanup is almost finished, Cavazos said his community wants restorative justice. He wants to see a public forum acknowledging the damage done to the community by Kerr-McGee, especially to Mexican families who unwittingly bought contaminated properties.

“The narrative of the past has been lost. Ever since the ‘80s they’ve tried to fast-forward,” Cavazos said. “People today are still sick from Kerr-McGee.”

Kerr-McGee no longer exists. Many residents don’t expect help for their ongoing health issues. And in the absence of an official response, some are trying to keep the story alive on their own.

Abraham Marshall, a former resident whose wife suspects her autoimmune issues are factory-related, recently published the first of a series of youth science fiction books about West Chicago’s thorium history to honor victims. Bartlett and a student filmmaker compiled her neighbors’ stories into a 2016 documentary film, “A Lifetime Irradiated.”

“Companies continue to profit off of people who are vulnerable in society,” Bartlett said. “What would be ideal is that enough people are aware of these kinds of practices so it doesn’t keep happening.”

For Ester Escamilla Hughes, talking about West Chicago’s thorium-laced past is about finding support for the ongoing health issues that have cropped up for her and other residents.

The two sisters will never know for sure if living near the factory as children contributed to their ongoing chronic illnesses. Jacobo once asked her endocrinologist about it and was shut down. “It made me feel like I asked a dumb question. So I never went down that road,” she said. Among the 125 extended family members on her mom’s side, no one has the kind of serious health issues she and her sister have.

Other doctors told Hughes that her illnesses might have been triggered by working at a quarry, where she was exposed to silica dust. She wonders if growing up around nuclear waste was the underlying problem that her work hazards exacerbated.

Talking with other residents has brought Hughes some comfort that she’s not alone.

“When you’re sick, you think, ‘Oh my gosh, am I crazy?’ Sometimes the doctors make you feel like you’re crazy,” she said. But knowing that other residents also share her story helps. “We are feeling something. Something did happen. And it’s still happening.”

Correction 7/28/22: An earlier version of this article incorrectly stated that the Kerr-McGee factory is north of the Arzola’s home.

Check out our FAQ for answers to common questions about West Chicago radiation contamination.

Have a story about West Chicago that you want to share? E-mail us at [email protected].

This story is available for free republication. Please contact us at [email protected] for permission and details on how you can use our reporting.

This reporting was supported by the International Women’s Media Foundation’s Howard G. Buffett Fund for Women Journalists and an award from the Institute for Journalism and Natural Resources.

Special thanks to Erika Bartlett, who shared documents and photos from her years of personal research for this story.