Photo by Martin Sorrondeguy

Photo by Martin SorrondeguyHistorian Mike Amezcua examines the origins and anti-gentrification struggles of Latinx Chicago neighborhoods like Pilsen and Little Village.

The stories of Mexican neighborhoods in Chicago are the stories of working-class immigrants, mixed-status families and Latino entrepreneurs, artists and activists seeking to build their own sanctuaries. But these stories are under constant threat of erasure by multiple gentrifying forces, which continue to displace and exploit communities in Latinx centers like Pilsen and Little Village.

Want to receive stories like this in your inbox every week?

Sign up for our free newsletter.

In “Making Mexican Chicago,” a new book published by The University of Chicago Press, assistant professor of history at Georgetown University Mike Amezcua foregrounds the Mexican Americans who made these neighborhoods their own in the face of white resistance. In addressing their everyday creation of a home despite systems built against them — whether immigration policy or racial capitalism — Amezcua zeroes in on enduring tensions in Chicago too often concealed under a veneer of progressive attitudes.

The following excerpt focuses on the changing face of Chicago’s Southwest Side in recent years, spotlighting the transformation of 18th Street in Pilsen and the activism of groups like the Gage Park Latinx Council.

In 2017, Casa Aztlán was sold to a condominium developer who swiftly painted over the murals that had adorned its exterior walls and symbolized the pride and struggle for self-determination of an earlier generation of artists and activists during the Chicano Movement of the 1960s and 1970s. Community members considered this an affront to the long history of Pilsen as a cultural sanctuary for Mexican immigrants and Mexican Americans and its decades-long struggle to reclaim resources for the community and mark its built environment with symbols of dignity and social justice. “It’s a big loss,” said Byron Sigcho of Pilsen Alliance, an antigentrification advocacy group, “[Casa Aztlán was] not only a space, but culture, identity, decades of community services like adult education classes, immigration services … it really reflected the history of the community.”

The erasure of Mexican and Chicano landmarks has been part of a long and ongoing history of resource looting to remake the central city and, in the process, unmake Mexican Chicago and other Latino communities across urban America from Boyle Heights to Brooklyn. Although they achieved some degree of success in securing residential and class mobility across metropolitan regions, Black and Brown working people overwhelmingly remain the custodians of the central city, a resource ever more valuable to global neoliberal capitalism. In parts of Mexican Chicago, such as Pilsen, residents are facing a ruthless drive toward a “renaissance” in which the profit imperatives of the wealthy class exploit the powerlessness of disadvantaged and racialized working people whose very lives are “in the way” of someone else’s good deal. Casa Aztlán has been but one of many buildings that have succumbed to this savage renaissance led by venture capitalists, luxury-condo developers, and land speculators who have legally confiscated buildings and houses in working-class Latino communities to make them suitable for a wealthier class of consumers who can afford higher rents, mortgages, and taxes. Many Latino-serving Catholic churches have also closed their doors due to the displacement of local parishioners from the neighborhood, eliminating not only places of worship but also critical resources for community organizing.

A creative class urbanism has followed on the heels of Latino working-class settlement. Armed with neoliberal capital and city hall incentives, a wave of niche entrepreneurs have opened breweries, coffee shops, bars, and restaurants on the same real estate that decades before was the site of sweat equity projects from which Mexican immigrants hoped to build sanctuary in America. Nourishing business opportunities has been a hallmark of Latino communities in Chicago for years, but the new wave of creative class businesses has fueled property speculation, increasing rents and leading to the eviction of working-class Latinos and businesses. The panaderia has been supplanted by the pour-over. A walk down Pilsen’s 18th Street in 2021 showcases this savage renaissance in all its exposed inequality; the thoroughfare has become an unevenly contested terrain between the ever-dwindling means of the Mexican working immigrant and the ever-increasing demand for luxuries desired by the creative class. To attract more of the latter, a surge of unfettered capital and digestible fictions have descended upon Pilsen’s buildings, storefronts, and public and private spaces, gentrifying Latino urbanism and its characteristic aesthetics and pedestrian culture.

Far from the postindustrial liberalism often attributed to the creative class, some of these business owners and their patrons have been flagrantly anti-Mexican and anti-Latino. Some CEOs of hipster bars and restaurants have behaved much like corporate entities who depend on underpaid Latino immigrant laborers but exploit and abuse them. Stories of immigrant workers (especially undocumented workers) being stiffed on their wages, subjected to sexual abuse, or otherwise mistreated go largely unreported for fear of retribution. On occasion, the bars have also become the uninhibited playgrounds for wealthy and right-wing white-collar professionals who become inebriated and disrespectful toward longtime residents. In 2018, after a violent outbreak where drunken patrons wearing Donald Trump paraphernalia attacked a Latina community member on 18th Street, a Pilsen-based queer women of color group organized a boycott against all “gentrifier bars.” When the bars failed to address or apologize for the violence, the group responded by asking the community during a social media press conference to “boycott any fucking gentrifying space in Pilsen because they don’t care about us, and they never will, they only care about their money. Gentrification is a violent practice run by capitalism.” The fracas underscored for local residents the vortex of racism, violence, displacement, and erasure that comes with every new hip bar or business.

Even when the patrons and owners of the new businesses do not embrace the blatant racism of the Trump era, the carnage of gentrification remains, reflected in more subtle forms of erasure—for instance, the wave of new breweries that have recently opened in Chicago’s Southwest Side as part of a craft-beer resurgence in the United States. In many cases, these erasures are fueled by artisans whose passion for their craft is commendable. Nevertheless, the architecture and design of the breweries evoke a revisionist origin story that contributes to the erasure of local neighborhoods. These breweries are designed in the aesthetic vernacular of creative-class urbanism that draws from both quasi-industrial and postindustrial elements, utilizing rehabbed warehouses, factories, storefronts, exposed beams, wood paneling, brick, and other raw materials to present a more polished version of a different economic era. Rather than building equity-based partnerships that dignify, recognize, and resource share with the Latino communities in which they operate, many breweries ignore Mexican Pilsen or Mexican Chicago altogether. Instead, the aesthetics evoke the culture of the area’s nineteenth-century Eastern European and German immigrants whose descendants erected barriers against Mexican immigrants and Mexican Americans before eventually fleeing the city. Thus, the new breweries romanticize and fetishize Pilsen and the Southwest Side’s built environment with a selective revisionist past while conveniently erasing the area’s Mexican history and presence. The question remains, however, whether creative-class urbanism can coexist with Mexican Chicago without contributing to its unmaking. If the past offers any clues, it is that the pursuit of appropriating communities and community resources for profit, a pursuit that relies on racial domination, is the bedrock of racial capitalism, and thus, is not built to share or willingly give up power or resources.

Masses of multigenerational and immigrant Latinos living in US cities have for years called attention to the precarity of their lives under systems of racial capitalism, in which economic prosperity continues to be built off of the inequities inflicted on working Brown people and workers of color more generally who are excluded from the rewards of the reinvested postindustrial city. The exploitation of Latino workers in service and food industries, construction, factories, fields, and domestic work has only exacerbated their urban conditions in the twenty-first century. From Los Angeles to Chicago to Brooklyn, Latino immigrants and multigenerational Latino families across urban America have been positioned to be the supporting cast to other people’s cushioned urban experiences.

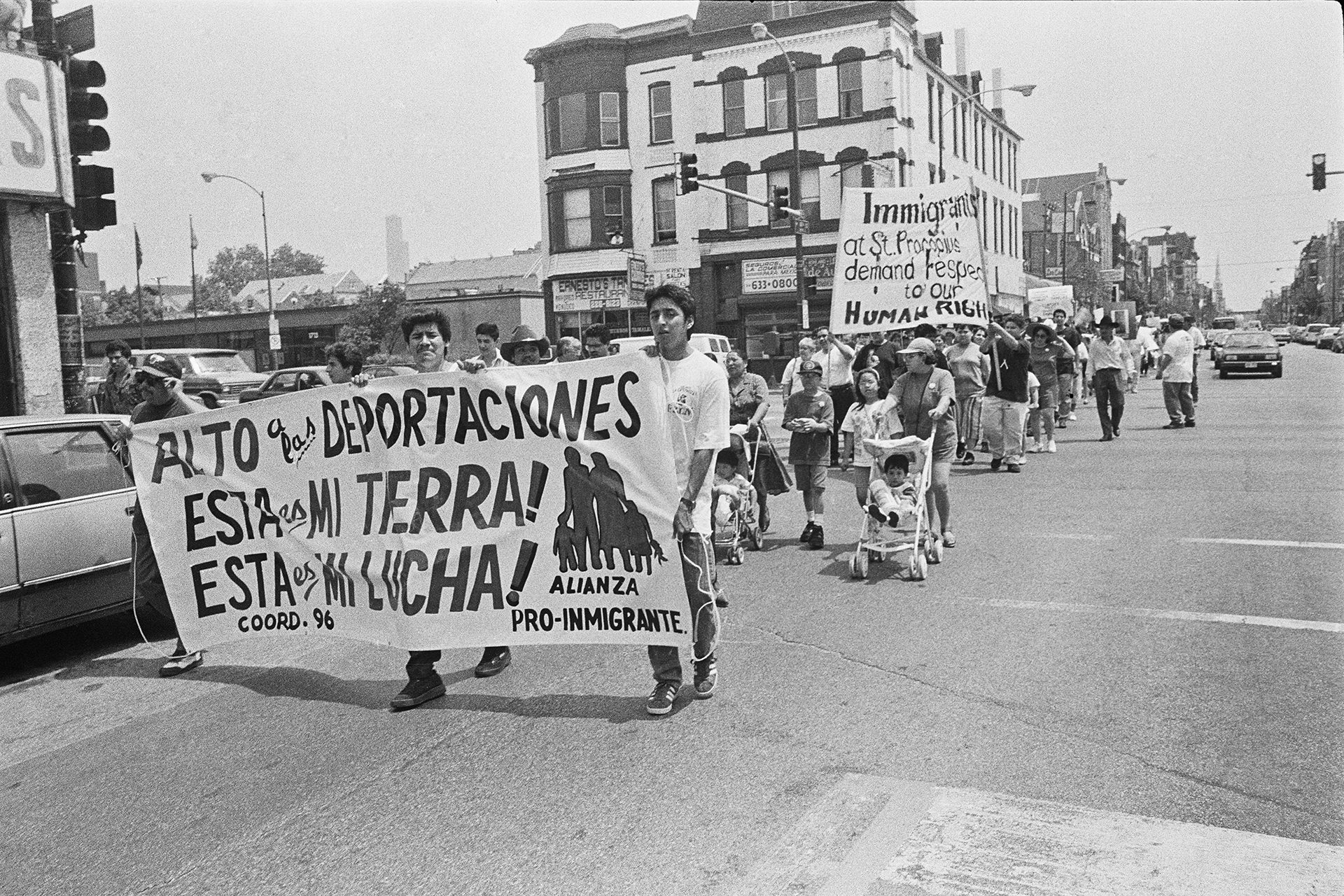

The unmaking of Mexican Chicago is not bounded by twenty-first-century history but has always coexisted alongside the building of Latino communities amid destabilizing episodes of federal and municipal disinvestment, economic restructuring, the immigration carceral state, political disenfranchisement, and predatory corporate reinvestment. While this book recounts much of that history, efforts by community organizations and housing activists working toward protecting the right to remain in the city have, for years, warned against the threat of displacement posed to Latino working-class residents by the unregulated forces of neoliberal capital and the nativist strain in US immigration policy. Resisting and persevering in the face of these forces has also been part of that long history. Just as in the 1950s, when Mexican community members from the Near West Side were targeted by the dual violence of urban renewal and INS deportation campaigns, Mexican bodies and their buildings came under threat in the 1990s. In 1996, housing and immigration activists in Pilsen rose up and resisted the intersecting vortex of displacement and deportation that was once again linked by the political and economic priorities of the decade that pursued neoliberal and nativist measures against immigrants and minorities. In 1996, President Bill Clinton signed the Illegal Immigration Reform and Immigrant Responsibility Act (IIRIRA), a punitive law that further criminalized Latino immigrants and increased federal agent raids in Latino communities, reducing due process in court procedures. Antideportation activists took to the streets—the very streets of Pilsen where deportation and gentrification were operating in tandem—to call out the conservative turn against immigrants by the Clinton administration. Pilsen residents marched along its main thoroughfare of 18th Street, carrying signs that read: “Stop the deportations,” and “This is my land! This is my struggle!”

That same year, housing activists mobilized public protests against the “yuppification” of Pilsen as well. Two years later, in 1998, the Frente de Artistas en Defensa del Barrio del Pilsen joined with housing activists when they penned a manifesto warning that Pilsen “is in grave danger of disappearing under threat of eviction” as corporate dollars permeated the community on the incentives given by city hall to raise the tax value of the area, pushing out the most vulnerable. Swaths of properties opened to real estate investors and white-collar professionals, drastically changing the face of Pilsen right at a time when arriving Mexican immigrants needed these communities the most. Between 1990 and 2010, the United States saw some of the greatest spikes in immigration from Mexico, with numbers climbing from 4.2 million in 1990, 9.1 million in 2000, to 11.7 million in 2010. This increase helped turn Chicago’s metropolitan region into the second largest concentration of Mexican immigrants in the United States, after Southern California. A significant percentage of these immigrants were undocumented, an always present element in Mexican Chicago, making transnational families with mixed status.

What began in 1996 as a community effort to protest the repressive apparatus of immigrant criminalization snowballed into a historic national movement for immigrant rights in 2006. That year, organizers from Mexican Chicago led La Gran Marcha, a series of massive nationwide protests numbering over 1.5 million people across 102 cities. In Chicago, marchers descended in the downtown Loop in a powerful show of support, surpassing 100,000 participants. Since then and through the Great Recession, the Obama administration’s deportation surge, the Trump administration’s mainstreaming of white ethno-nationalist rage, and a global pandemic, residents of Mexican Chicago have continued to fight to build a metropolitan sanctuary in the American city.

The outcome is evident throughout the Mexican Bungalow Belt, including Gage Park, once the seedbed of racial bigotry. Today, Gage Park is home to thousands of Latino immigrants and their mixed-status, multigenerational families. One of its new organizations, the Gage Park Latinx Council (GPLXC), has responded to the COVID-19 crisis by organizing fundraisers and creating a food pantry for families experiencing food and housing insecurity. Many of its community members work in high-exposure occupations as cooks, cleaners, and factory workers. Since the start of the pandemic, many have been laid off or furloughed. Amid the destruction wrought by the coronavirus, GPLXC has called into question the harmful paradox that simultaneously hails Latino immigrant workers as “essential” and “saviors” in a society that also treats them as expendable. Latinos in Chicago have had infection rates triple that of whites and a disproportionate amount of deaths. Along with its community organizing, GPLXC has also engaged, rather than ignored, Gage Park’s long history of racial exclusion with an aim to renew the politics of sanctuary and social justice after a violent resurgence of anti-Latino nativism in America. “Rather than allowing us to feel like Gage Park is merely a space we occupy, GPLXC is actively fighting for us to have a neighborhood that is truly nuestra tierra and ushering in a future where residents will never doubt they have a home,” explain its leaders.

Making Mexican Chicago reveals the decades-long struggle to build a sanctuary out of the central city in the face of state violence, political disenfranchisement, economic disinvestment, and the backlash of hostile white ethnic mobilizations. Only in a society constituted by neoliberal multiculturalism and racial capitalism can immigrants exist in a paradox of being essential but also expendable, deportable, and erasable. This book highlights the multivalent repertoire that residents took to achieve Latino-centered empowerment in the city as residents, business owners, and community organizations pushed for transformative change in the political economy that was all too casually augmenting inequality in the form of racial capitalism. Some community leaders worked toward resisting spatial containment and “barrioization”; others, such as Latino merchants, seized on the concentration of Mexican peoples in one place, hoping to create opportunity through Brown capitalism. In the process, the story of Latino community formation and migrant city building—the making of Mexican Chicago—has been the story of the pursuit of sanctuary even when it is far from reach.

Mike Amezcua will be speaking at the following events:

3/3: Virtual book talk at Northern Illinois University, NIU Latino Center, 6 p.m. Register here.

3/24: Virtual book talk at the Seminary Co-op, 6 p.m. Register here.

4/28: Meet the Author in-person event at the Newberry Library (60 W. Walton St.), 6 p.m.

Bring power to immigrant voices!

Our work is made possible thanks to donations from people like you. Support high-quality reporting by making a tax-deductible donation today.