Photo by April Alonso for Borderless Magazine/CatchLight Local

Photo by April Alonso for Borderless Magazine/CatchLight LocalChicago organizer Carolina Gallo provides support to survivors of domestic abuse who are often failed by — or fearful of — existing systems.

Carolina Gallo, 27, has been organizing for close to a decade. As a teenager in Chicago, she learned about social issues such as gentrification, racial inequities and homelessness through the youth program Young Chicago Authors. When she turned 18, she began organizing around a variety of issues she cared about, including housing rights, worker rights and immigrant rights.

Working with immigrants is especially meaningful to her. Born in Mexico, Gallo and her family moved to the United States in June of 2002. Ten years later, she applied for protection from deportation under the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals program, or DACA. Waiting overnight with other hopeful applicants at Navy Pier — which hosted Chicago’s first informational session about the then-nascent program — instilled in her a strong sense of community and an urgency to help.

“I realized that there was something greater at stake here,” Gallo said. “And that’s when I really decided I wanted to continue to be involved in the immigration rights movement.”

Gallo is now a client support specialist at a Chicago legal clinic that provides assistance to people impacted by gender-based violence, from helping them access shelter to accompanying them to immigration court. She also works with undocumented survivors of domestic abuse, many of whom are afraid to seek out legal remedies, although they are among the most vulnerable to this form of violence. A 2006 study published by Legal Momentum found that immigrant women married to male U.S. citizens face an abuse rate approximately three times higher than that in the general population. Abusers often weaponize immigration status to intimidate, inflict economic abuse on and deny privileges to their partners, among other tactics, according to the National Center on Domestic and Sexual Violence.

Borderless Magazine spoke with Gallo about how she centers social justice as a social worker and how she helps immigrants understand systems that often work against them.

News that puts power under the spotlight and communities at the center.

Sign up for our free newsletter and get updates twice a week.

I’ve always questioned society. We have all these problems — issues of policing, immigration, homelessness — and I was tired of just waiting for someone to fix them. I spent most of my early 20s lobbying for passage of the Student Access Bill that became the Retention of Illinois Students & Equity (RISE) Act, or the Alternative Application, which provides financial aid for transgender students, undocumented students and other students who run out of funding through FAFSA. That is something that I didn’t have when I went to college.

Now I work within the legal system, and I do the job of a paralegal and a social worker at the same time. I help domestic violence survivors feel empowered to make the decision to leave their situations. My job is more than providing or being present as an emotional support but providing different resources to help them stay afloat and decide for themselves what they need.

For instance, I help people apply for VTTC benefits, which is cash and food assistance; for access to therapy; for housing assistance and for unemployment benefits. The majority of the people stay because of financial strains or because they are not financially independent. It’s part of the abuse — that person manages the money or told you to leave your job. Immigrants also stay because they might fall out of status if they leave.

If people had basic needs met — if they had access to jobs that paid well, could afford to pay for childcare, had access to housing and a livable wage — we wouldn’t have so many domestic violence problems, period. People could just leave. Most people will go back seven times before they actually leave for good.

A lot of what I do is finding alternative solutions: Where can a person go, how can they get help without having to go to the police?

A lot of immigrants don’t want to work with the police. It gives them anxiety. The police work with ICE, the Department of Homeland Security and other government organizations to deport people. You could be taken into custody instead of your abusers.

Survivors of domestic violence have really horrible experiences with the police in general. The police are aware of the power dynamics at play, and they use that for their own benefit. They intimidate and treat the person without any sense of respect. When someone who has experienced domestic violence goes to the police, they are interrogated and asked questions that re-traumatizes them. Police also blame the person. It invalidates their experiences.

Read More of Our Coverage

If they do have to go to the police, how can you support them? Maybe we can call the police together or we make police reports. Maybe it means that I actually accompany the person to the police precinct. When you do go to the police, your job is to try to reduce the trauma this person is enduring.

Part of empowering people is allowing them to make decisions for themselves. You’re doing what they want to do for themselves. You’re not telling them what’s good for them, which might be things that they might not want to do.

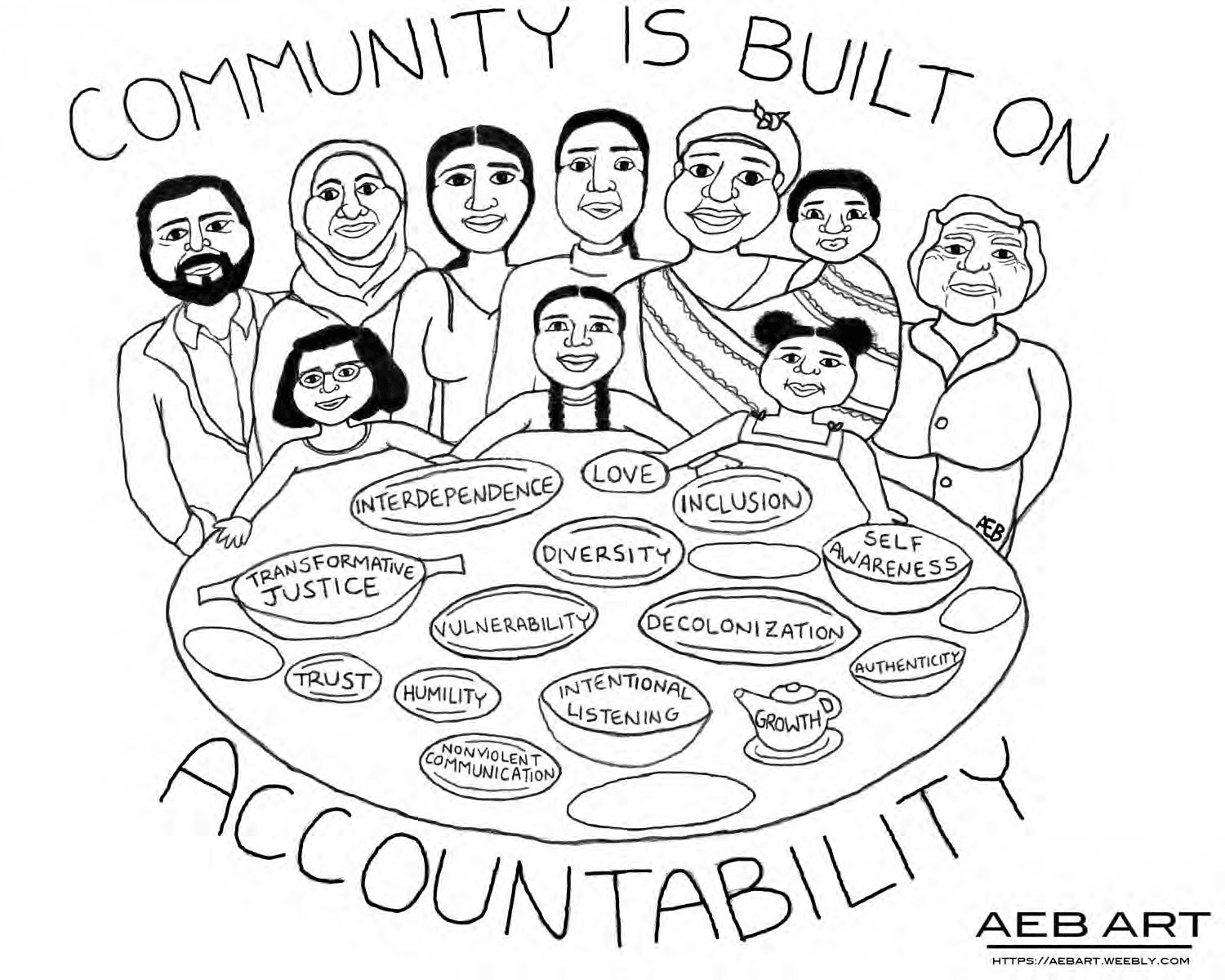

I am also part of a 40-hour training program that certifies other social workers and advocates so they can work with people who are experiencing domestic violence. It’s called The Network. They do several trainings throughout the year and partner with different organizations and people within the city. Everything is done from an abolitionist perspective. I am a regular presenter, and it gives me ideas for how to work outside the system.

We mostly work with people of color and immigrants. So a lot of the work is trying to mitigate the system, which wasn’t built for us.

Having a point person to maneuver the system in the same language they speak is huge. People can feel understood, less confused and more aware of what is happening in their case. They can be helped in a way that they know they are cared for, heard and acknowledged. They can feel less alone.

If they don’t understand what’s going on, they could lose their civil cases. Police reports could be written incorrectly because a police officer could not properly communicate with the immigrant and did not give a shit. That causes people to not be able to get certain benefits. They could also lose their children to the system and not be aware of where they are.

Even if I don’t speak the same language as my clients, there’s a way to connect with them by having cultural humility. That means acknowledging that one, as a social worker, might not know everything about someone’s culture but has the willingness to learn and navigate systems together. Just being aware that you are working with people from different countries, there might be cultural factors why they’re not talking to me. Having that cultural humility allows me to continue to build these relationships of trust and understanding and support, which I provide by using an interpretation hotline for clients whose language I don’t speak.

Social work is a very white field. It’s also a very dangerous field because you can actually cause a lot of harm to people if you lack that cultural humility to navigate the system with them. That’s something that is not oftentimes acknowledged completely by people who are white.

I took this job because I wanted to be a more well-rounded social worker who includes organizing and social justice in the work. I knew that was a huge necessity.

I have learned to navigate the system my entire life. If I’m able to help someone else do it, why not? It’s just like giving yourself what you didn’t have, and you’re able to make it easier for someone else.

I have also experienced domestic violence. I honestly think that makes a person who comes to me for help feel safer because I understand their lived experience. I’m also an immigrant, and when I tell people that, they feel more connected. They know that I understand, and they feel less alone. That’s important.

When people find that support, it’s a beautiful thing. I think that’s what I love about my job: When you find alternatives and build support networks, and people don’t go back, it’s a wonderful day.

I am text block. Click edit button to change this text. Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit. Ut elit tellus, luctus nec ullamcorper mattis, pulvinar dapibus leo.

I’ve been very lucky to have a lot of community support in my life. I completely believe that it does take a village to raise a child. I also think that it takes a village to change things.

The only people who are saving this community are the community members or neighborhood organizations. They’re the only ones helping people apply for relief or learn about vaccination or giving them masks and hand sanitizer. They’re giving people food on a daily basis.

Religious community is also important for a lot of immigrants and many people who are experiencing domestic violence. When a place of worship respects them and believes them, it changes them completely. They feel validated.

People want to be affirmed in their choices. They want to feel that they weren’t the bad person because oftentimes they are told that they are. These people are complex. They’re more than their trauma. Honoring that and honoring their full personalities — that makes them happy.

The National Domestic Violence Hotline number: 1-877-863-6338

This story was produced in partnership with CatchLight Local and the Institute for Nonprofit News and is part of our series, Mi barrio me respalda [My neighborhood has my back], a monthlong bilingual series reported by, for, and with Latinx Chicagoans.