Gema Lowe, who migrated from Mexico to America 30 years ago, describes her journey as an advocate for undocumented immigrant in Grand Rapids.

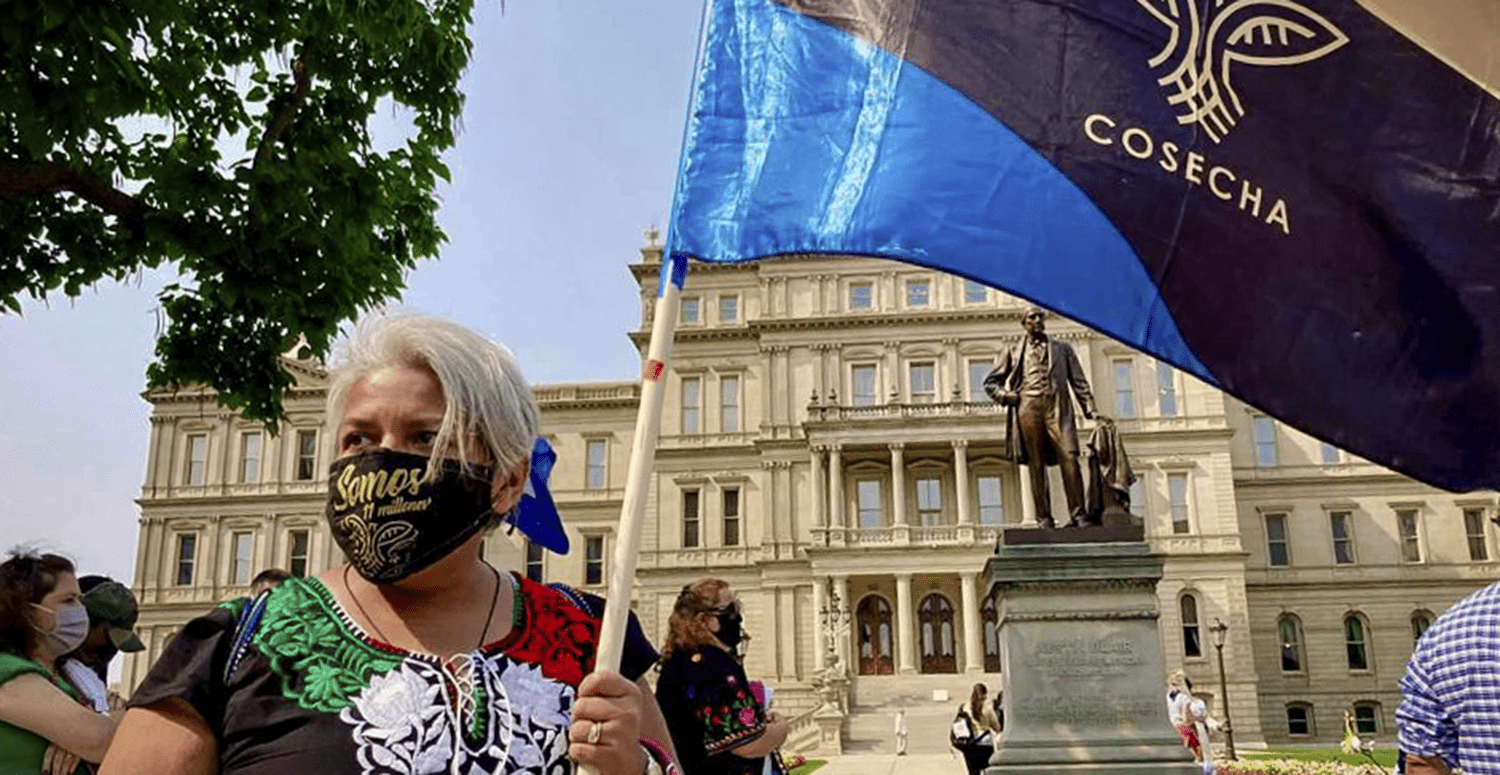

Gema Lowe is an undocumented Mexican immigrant, mother and former factory worker. She is also a co-founder of the Michigan chapter of Movimiento Cosecha, a national, non-hierarchical, immigrant-run movement that advocates for the permanent protection of all undocumented workers. Through non-violent, non-cooperative and non-partisan means, Cosecha organizes workers, activists and artists to demonstrate that immigrant labor is essential to this country.

Lowe talked to Borderless Magazine about losing her lawful immigration status and what inspired her to become an organizer for immigrants like her.

My resolve to be an organizer is partly personal. I’ve seen the system play out for workers like me. I’ve seen that once you’re injured and you’re not performing, the system looks for excuses to get rid of you, especially undocumented immigrants like myself.

I was born in Guanajuato, Mexico, and I lived there until I was 19. As I was finishing up high school, my dad died. He was the breadwinner for our family, and when he died it was just too difficult for me to continue my education. But I had uncles in the United States who offered to bring me over, just for a little bit, to learn English. I guess it’s the story of every immigrant: You don’t think that you’ll stay for as long as you do. I’m 49, and I’ve been here for 30 years.

Gema Lowe holds up her kindergarten certificate of completion in Magdalena de Kino, Sonora, México in June 1978. Photo courtesy of Gema Lowe

When I came to the United States, it was a culture shock. I was legally documented at one point, through marriage, but everything changed in 1996 with the Illegal Immigration Reform and Immigrant Responsibility Act. At first, I had lawful conditional status through my marriage. But right when I would have been eligible for permanent status, the laws changed, and the time frame in which I could legally petition for permanent status was shortened from four years to three. Because of that change, I had already missed the cutoff time by a year. Immigration lawyers told me there was nothing I could do to regain my status.

Losing my status didn’t initially feel that different. My oldest daughter was born in 1996, so I was more focused on being a mom. I had this brand new human being with me, and I threw myself into my family and my work, like any other person would.

But I would learn that being an undocumented worker has its complications. In 2011, I injured my knees at the factory where I worked. In Grand Rapids, I’d held different factory jobs, mostly administrative and manufacturing, but with my injury I had to stop working in factories. I lost my job, my health and eventually my house. I faced a lot of struggles trying to get proper medical care, and, being undocumented, I wasn’t able to claim disability insurance. I was only in my 30s, and surgeons said I was too young for knee replacements. I wound up being on crutches and in a wheelchair for two years, unable to walk.

Gema Lowe, center, and, from left, Patricia Villarreal-Dunn, Gaby Pacheco and Methodist pastor Jorge Rodriguez, travel to Washington, D.C. to advocate for the immigration reform bill that passed in the Senate that year, on April 22, 2013. Photo courtesy of Gema Lowe

I needed help and I wasn’t getting it. I had to advocate for myself. Before this, I was focused on my little bubble: my house, my kids, my job. I was not very aware of my community. But when my health dramatically changed, so did my perspective. As I healed my knees, I began working with a worker center in Grand Rapids. There, I helped other workers navigate injuries like my own, as well as wage theft and unsafe work conditions.

I first heard of Movimiento Cosecha in 2017 through the executive director of the worker center, who learned that Cosecha was planning a national gathering in Boston. She invited me to come along. That trip changed everything for me. I remember, like, 400 people gathered in one room at this university. I think I was the only one with gray hair. We went to Old Navy and danced inside and shut down the store. It was very, very cool. I immediately felt that Cosecha was what our movement needed.

In February of 2017, the ground was fertile to plant Cosecha in Michigan. Trump was being his “bad hombre” self more and more each day, and the people were ready to do something about it. Our first march for Cosecha Michigan brought out 2,000 people in Grand Rapids. For a regular march, if 500 people showed up, that was big. I usually have to drag my daughters to events. But this time, they were the ones who brought their own signs that said “I’m a proud daughter of an immigrant.”

Gema Lowe’s daughters, Jazpe Cano-Quintero and Jade Lowe, during the “Un dia sin inmigrantes” (A day without immigrants) march organized by Cosecha Michigan on Feb. 16, 2017 in Grand Rapids, Mich. Photo by Roli Mancera courtesy of Gema Lowe

In my years prior to Cosecha, everything was a slow process. We had case-by-case victories. If a worker wasn’t paid their wage, we’d fight together to get the wage back. If a worker was working in poor conditions, we’d fight to change the conditions. But that was the extent of it. It wasn’t social change. Cosecha has taught me all about people power — the power of taking our liberation into our own hands. And that’s what we need now.

In Grand Rapids in 2019, we ended local law enforcement contracts with ICE, as well as ICE holds. These practices were established in Kent County in 2012 during the Obama administration: ICE formed contracts all over the country with local governments to increase deportations of undocumented people who were often stopped for petty charges and held in detention centers.

But in 2019, Cosecha Michigan saw two opportunities to end these practices. On a national scale, we started seeing kids in cages, which made ICE look so bad in the public eye. Locally, there was the story of U.S. Marine veteran [and U.S. citizen] Jilmar Ramos-Gomez who suffered from PTSD and trespassed on a hospital helipad. He was arrested by police, who contacted ICE, who took him to a detention center where he almost faced deportation. That story made the news and emphasized that this system is so messed up and that we need to end ICE holds and contracts.

Gema Lowe in January 2015. Photo by Roli Mancera courtesy of Gema Lowe

And when we ended the city’s relationship with ICE, it had an immediate impact. Immigration lawyers called us to say that their clients got out because of what we did. We literally snatched our community back from ICE, and the undocumented community did it by organizing together.

As an undocumented person, I don’t fear deportation. I think that if it ever happens, I will have a whole community, and together we will fight to defeat this unjust immigration system. I haven’t been back to Guanajuato since I lost my status over 20 years ago, and while I do have relatives in Mexico, I feel more Michigander than Mexican.

Of course I am very proud of my heritage and my ancestry, but I was also raised by this country. My mother lives here with us now. My oldest daughter graduated from college. Even with two kids of her own, she pulled through and graduated, and I’m very proud. My youngest is a freshman in high school, and she’s very good in school. I have two grandbabies here. All my roots are here now, so I don’t fear.