When Abu Nabil* tastes shish barak (ششبرك), he remembers his mother.

When Abu Nabil* tastes shish barak (ششبرك), he remembers his mother. The traditional Syrian pasta stuffed with ground beef and spices, which is cooked in yogurt and served hot over rice, was a dish she would make only for him.

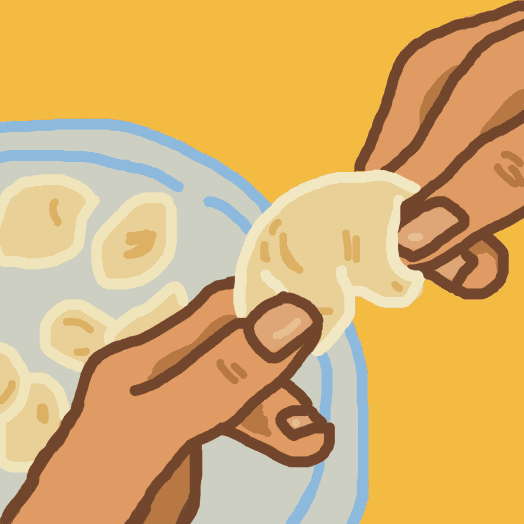

“Everyone in the family likes shish barak, but no one loves it like me,” he says, remembering the hours his mother would take to gently fold each individual ravioli before adding them to a pot of warm yogurt.

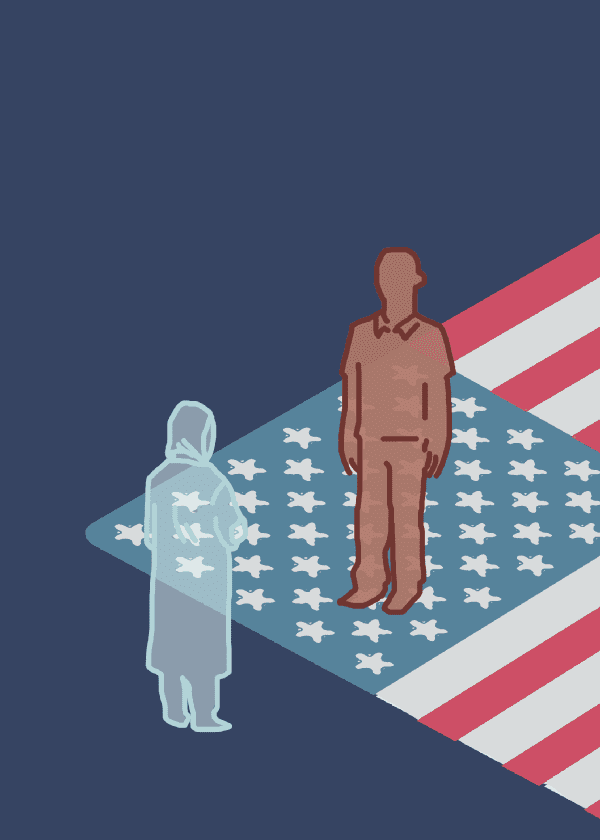

It’s been eight years since he heard his mother’s voice on the phone, enticing him to come over to his family’s Damascus apartment with the promise of shish barak. Since 2014 he has lived as an asylum seeker in the United States, awaiting the court’s decision on whether he will stay or leave.

Abu Nabil came to the United States from Dubai, where he had worked at a news station. There, he spoke out against everyone doing wrong in Syria from ISIS to the rebels to the government. He gained many enemies, he says, which worried his family back in Damascus.

“The last thing my father told me before I left Syria in 2009 was, ‘Son, please do not speak of politics with anyone,’” Nabil says. Politics had long been a taboo topic in his house and no one was allowed to discuss it. “Not just my parents, my entire family. Even when I would say something growing up about our system in Syria they would shush me saying, ‘We don’t talk about that. We don’t talk about that here.’”

The fear of punishment was a specter that haunted his family after relatives disappeared into jails during the Hama uprising of 1982. “I had two cousins thrown in prison: one for 17 years and the other for 11 years for no reason. They were simply captured for being young men in Hama that was in an uprising at the time,” says Nabil.

When security agents came to take Nabil’s father to prison in 2012 to punish him for his own work at the news station, his family’s worst fears were confirmed. His father bribed the officers to not take him away, and then the family fled to Egypt. Their home was later shelled. “I’m not sure if there is anything left of our home,” says Nabil.

Fearing for his own life, Nabil decided to leave Dubai and went to the U.S. Consulate in desperation.

“I never thought the U.S. Consulate in Dubai would give me a visa, but I applied to study to be a pilot in the United States,” he recalls. “I remember the consulate officer smiling at me and asking, ‘Why do you want to be a pilot?’”

“You know at this point, I had nothing. I literally had lost everything. Our house was bombed in Damascus, my family was forced to flee to Egypt and my passport was almost expired.” Though getting a student visa was life or death, the only answer he could muster was, “Because I look like one,” he remembers.

The officer gave him a visa and he applied for asylum in the United States in 2014. His fate in the United States is uncertain and he is unsure whether the Trump administration will let people like himself stay.

Nabil misses his family, especially his mother, who he hasn’t seen since 2012. Their last meeting was a difficult one. He was visiting his family in Egypt and his mother cried. She wasn’t happy that he was going back to Dubai. His news station had already lost several workers in Syria and they knew the danger was closing in on him. “She believed it was the last moment she would hold me,” he says.

It was also hard for him to see his family suffering as refugees in Egypt. His mother wanted leave Egypt for Istanbul or Sweden because life in Egypt for Syrians meant a life of poverty and oftentimes abuse. Sometimes people on the street would curse his family telling them to leave their country. Without work, Abu Nabil’s father could not afford to send his little brother to grade school, or his sister to high school. His sister, now 20 years old, never finished high school.

“They were depressed all the time. All of them crying,” he remembers. “When you are separated from your family and you hear them cry all the time, it’s very hard on your soul.”

Today, Nabil’s family lives as resettled refugees in Australia. Without a passport, he finds himself again separated from his mom. “I don’t regret anything I’ve done. But if I was asked to do it again I wouldn’t want my family to go through the things they went through because of me. I know they are safe now, but they went through hell. There is nothing harder in life to see your own father cry, and it is because of you,” he says.

Then again, he can’t live life in silence. “If the situation were different, and my family were safe, I would do it again.”

This New Year, a friend invited Nabil over to make shish barak and to taste home again. It was the first time he tried his hand at his mother’s dish and he laughs remembering the experience. “I didn’t expect it to be that difficult, but when I tried it it was really difficult. When I was cooking it with Yasino, I was like ‘Oh my God, Mom, now I know why you were complaining all those years!’”

Even though he is separated by an ocean, it took him home, just for a taste.

Shish Barak with Yogurt — 6 servings

Shish barak is a traditional Syrian dish found in the 15th-century Damascus cookbook entitled “Kitab al-Tibakha” which is made of tiny meat dumplings cooked in a plain yogurt stew. It’s a traditional food in the tabeekh tradition, Arabic home food that is not usually found in restaurants. Shish barak is traditionally served over rice.

For the shish barak dumpling dough:

5 cups of flour

1 teaspoon salt

2 and 1/4 cups of water

1/4 teaspoon yeast

1/2 cup of warm water to mix with the yeast

1/8 teaspoon of sugar to mix with the yeast

For the dumpling filling:

1 pound coarsely ground beef

1 small onion, finely chopped

1 tablespoon olive oil

1 teaspoon salt

1/4 teaspoon white pepper

1 pinch of cinnamon

1 pinch of black pepper

1 pinch of cumin

1 pinch of ground cloves

Handful of pine nuts

For the yogurt sauce:

5 cups of plain Greek yogurt

1 cup of water

3 tablespoons cornstarch, dissolved in ½ cup water

3 cloves garlic, crushed

1 tablespoon vegetable oil

1 teaspoon salt

1 squeezed lemon (to taste)

Filing

- Sauté the onions with a bit of olive oil until translucent for 10 mins.

- Add the ground beef, spices, salt. Mix well and then sauté until the beef is cooked for about 10 minutes.

- Add the pine nuts in the last 5 minutes. The meat stuffing is now ready.

Dough and stuffing

- To prepare the dough, sift the flour in a bowl with some salt.

- In a separate bowl, add yeast and sugar to warm water.

- Gradually add water to the flour, then knead to obtain a soft dough. Cover the dough with a plastic wrap and put it in the refrigerator for 30 min.

- To make the shish barak dumplings: on a lightly floured surface, roll the dough using a rolling pin until thin.

- Cut the dough into 1.5 inch small circles using a bottle cap.

- Place 1 teaspoon of filling in the center of circle of dough and fold in half. Press edges together, sealing the filling, then squeeze both corners together to create a circle dumpling shape. Make sure the dumplings are sealed well.

To prepare the sauce

- Pour 5 cups of plain yogurt, 1 cup of water and cornstarch in a pot and stir continuously on low heat until it reaches a simmer. It is very important that heat is very low. Stir continuously in a circular movement until yogurt thickens then reduce the heat.

- In a small skillet, fry the crushed garlic and fresh cilantro with olive oil, then and add them to the yogurt.

- Add juice from 1 freshly squeezed lemon.

- Add the shish barak dumplings, then stir gently on low heat for 15–20 minutes until the shish barak dumplings are cooked.

- Serve hot as a soup. In each individual plate, place a serving of rice and shish barak dumplings and cover with yogurt sauce.

*Names and certain details of the story were changed to protect the subject’s identities.