I was welcomed, and I’m thankful.

I was welcomed, and I’m thankful.

I owe my life and the lives of my wife and children to U.S. refugee law and the compassion of the American people. It is difficult for me to reconcile the anti-refugee actions of President Donald Trump on January 27 with the generosity I experienced when I arrived in this country 14 years ago, fleeing Somalia’s civil war. America gave me a second life. Now, I wonder what will happen to Syrian refugees, who want only peace.

Before I arrived in the United States, my family and I lived in the Dadaab refugee complex in Kenya, the largest refugee base in the world which holds more than 320,000 East Africans fleeing war. Almost 80 percent of Dabaab’s residents are women, most are Somalis and many have only known Dabaab as home.

Life there was never free: our movement was restricted and there were many dangers for women. Often times, they were raped when they went outside the camp to collect wood for fire or while fetching water for cooking.

We came to Dabaab from our home in Somalia, which we were forced to leave when we were attacked during the war. Some members of my family were killed, and I saw loved ones tortured and raped in front of me.

By luck, I found a way to reach America as an asylum seeker. But starting a new life in America meant that I would have to leave my family behind. It pained me to know that I couldn’t protect my wife and children in the camp anymore, and I missed them dearly.

When I arrived here in 2001, I was depressed. I was worried about my family and had to deal with the trauma of torture without their support. It was through the kindness of so many Americans I met — social workers, legal aid providers and good Samaritans — that I was able to put my life back on track. They helped me overcome my depression and fear and navigate the rigorous asylum process. They provided moral support as I underwent security screenings and had my fingerprints taken six times over the course of the application process so the Department of Homeland Security could ensure that I had not been involved in wrongdoing here or outside the country.

When I finally was approved for asylum protection and allowed to apply to bring my family to safety, they again supported me while I waited for my wife and children to go through their own security screenings — a process that took two years. My lawyer, who defended me in court on a pro bono basis, even drove a U-Haul truck all the way from the suburbs full of furniture so my family would have a furnished apartment when they arrived. She and the many others who helped me are the America I know.

Because of them, I am able to be a part of society again. When you are tortured, you lose your trust in man. Therapy here has helped restore my faith in humanity. In my therapist, I saw that there are good people in the world who are doing good, despite those doing bad.

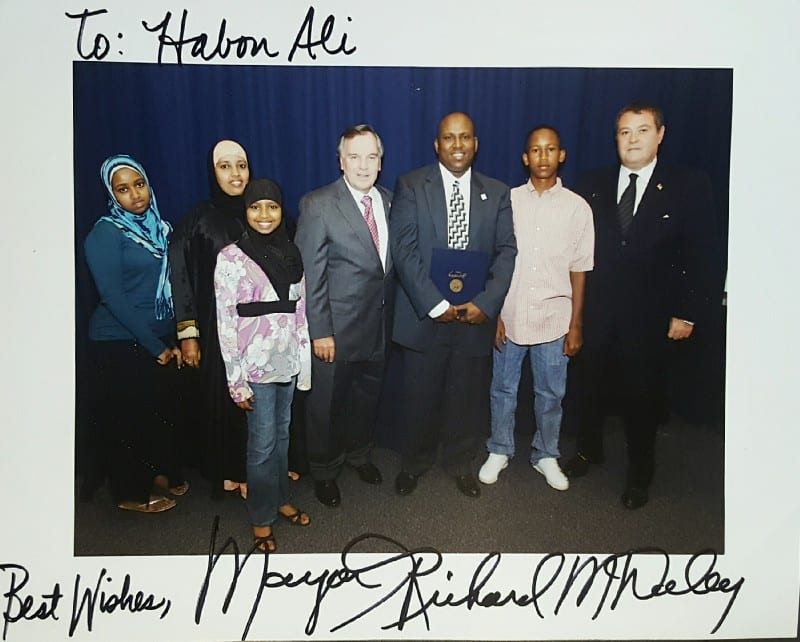

In May of 2016, I became a U.S. citizen. Since then, I’ve dedicated my life to giving back to the country that has given me so much and to helping other refugees still in the early stages of rebuilding their lives. I direct them to the organizations that helped me, interpret for Somali and Swahili speakers during their meetings with attorneys and immigration interviews and accompany them to doctor visits. I share my family’s story so that people can understand the realities refugees and asylum seekers face, and the complicated process they must go through to get legal protection in the United States.

As a father, it pains me to see the images of Syrian refugees on TV who are traumatized from the persecution they’ve escaped, but still in limbo, separated from their families and often deprived of food and other basic needs. That is how my family lived for nine years before they were able to join me in Chicago. I was in their shoes.

While I watch the actions of President Trump and his supporters, I ask myself what happened to that compassion? We must all remember our humanity and our country’s promise to welcome strangers and respond with compassion to those in need. While I have lost faith in the sympathy of those in power, the people demonstrating in airports have renewed my strength in these dark times. Those protestors are the faces of the America I know and love.

I was proud to be welcomed to this country, and I am deeply thankful for the opportunities me and my children — now in college — were given. I only ask: Please don’t close the door on Syrian refugees. Their futures depend on it.

Written by Abdinasir Kahin with help from Sarah Conway. Abdinasir Kahin is a taxi driver and member of Board of Directors of the East African Somali Community in Chicago.