Colin Boyle/Block Club Chicago

Colin Boyle/Block Club ChicagoDos años después de que empezaran a llegar a Chicago autobuses cargados de niños inmigrantes, muchos han aterrizado en escuelas donde la mayoría no habla español. Los conserjes y los maestros de guardería están asumiendo el papel de traductores, pero los alumnos siguen quedándose atrás.

Este reportaje fue una colaboración producida por Chalkbeat Chicago, una redacción sin ánimo de lucro que cubre las Escuelas Públicas de Chicago y Block Club Chicago,una redacción sin fines de lucro enfocada en los vecindarios de Chicago.

Gabriela Aquino Ruiz confía en una aplicación de traducción para aprender, pero algunos de sus profesores hablan tan rápido en inglés que el software no puede seguirles el ritmo.

A esta niña de 12 años, de voz suave y que sólo habla español, le encanta leer, pero en su escuela -la Isabelle C. O'Keeffe School, en la zona sur de Chicago- no hay libros en su lengua materna, y le cuesta hacer amigos, dice.

Gabriela echa de menos su colegio en Venezuela, de donde ella y su familia emigraron en octubre.

"Quiero aprender", dijo en español a través de un traductor. "Me siento frustrada cuando llego a casa".

Gabriela es una de casi 9.000 estudiantes inmigrantes matriculados en las escuelas públicas de Chicago en abril. Muchos de esos estudiantes están abandonando los refugios y encontrando una vivienda que les proporciona la estabilidad que tanto necesitan.

Noticias que ponen el poder en el punto de mira y a las comunidades en el centro.

Suscríbase a nuestro boletín gratuito y reciba actualizaciones dos veces por semana.

La familia de Gabriela se trasladó de un centro de acogida en Little Village a un apartamento en South Shore, el barrio donde más familias se han reasentado en Chicago a través de un programa estatal que les ayuda a cubrir el alquiler, según datos obtenidos por Chalkbeat y Block Club Chicago a través de una solicitud conforme a la Ley de Libertad de Información.

Pero la promesa de la vivienda tiene un coste: Las familias se están trasladando a barrios más asequibles que también son algunos de los más segregados de la ciudad. Como resultado, los estudiantes están aterrizando en escuelas con poco o ningún personal bilingüe o apoyo, según los datos obtenidos a través de solicitudes de registros abiertos y más de 50 entrevistas con familias, profesores y expertos.

Esto ha provocado que algunos alumnos se retrasen aún más en sus estudios, que los conserjes asuman funciones de traducción y que los directores de los centros tengan dificultades para cumplir el requisito estatal de impartir enseñanza bilingüe si la matriculación de alumnos alcanza determinados umbrales.

La oleada de nuevos estudiantes, muchos de los cuales huyen de la agitación política y económica en países de América Central y del Sur, está dejando al descubierto las grietas de un sistema escolar que durante años ha luchado por cumplir plenamente las leyes estatales y federales sobre educación bilingüe.

Incluso antes de que los autobuses con migrantes comenzaran a llegar en oleadas desde Texas en 2022, las escuelas públicas de Chicago no cumplieron plenamente con múltiples auditorías internas y estatales relacionadas con la instrucción bilingüe, según muestran los documentos.

Las escuelas de CPS que ya contaban con programas bilingües no han cumplido una serie de requisitos, como impartir enseñanza bilingüe en las asignaturas básicas a todos los alumnos que la necesitan, contar con profesores debidamente titulados y enseñar a los alumnos su país y cultura de origen. Ahora, un grupo de escuelas adicionales que han matriculado oleadas de estudiantes inmigrantes necesitan reforzar el personal.

"Nos preocupan mucho los desiertos lingüísticos de la ciudad... donde no hay servicios para los estudiantes de inglés", dijo Karime Asaf, jefa de la Oficina de Educación Lingüística y Cultural del distrito, que supervisa la enseñanza para los estudiantes de inglés.

En marzo, al menos 72 escuelas K-12 de todo el distrito tenían vacantes para personal bilingüe o profesores certificados para enseñar inglés como nueva lengua, al menos una cuarta parte de las cuales se encuentran en los 10 principales barrios a los que se trasladan las familias solicitantes de asilo.

Funcionarios del distrito dijeron que la creación de programas bilingües y el cumplimiento de las auditorías requieren encontrar profesores debidamente certificados, lo que ha sido un reto nacional. Señalaron los esfuerzos más recientes, como la contratación de estudiantes de CPS para convertirse en profesores, pero añadieron que CPS necesita más financiación.

"Siempre hay una necesidad de apoyo adicional y mejoras en el proceso, y estamos trabajando para asegurar más fondos de los gobiernos estatales y federales para apoyar a todos nuestros estudiantes", dijo el portavoz de CPS Sylvia Barragán.

A la pregunta de por qué el distrito y la ciudad siguen luchando por proporcionar apoyo a los estudiantes inmigrantes, el alcalde Brandon Johnson dijo a Chalkbeat y Block Club que las familias solicitantes de asilo se están asentando en "barrios históricamente desinvertidos", lo que ejerce "presión sobre ese sistema que ya está lastrado", refiriéndose a las escuelas de barrio que, en su opinión, carecen de los recursos adecuados.

Como antiguo profesor de secundaria y organizador del Sindicato de Profesores de Chicago, Johnson ha pedido que se invierta más dinero en las escuelas de barrio.

En respuesta a la rápida llegada de estudiantes inmigrantes en los últimos dos años, CPS abrió un "centro de bienvenida" en el instituto Roberto Clemente y está trabajando con la ciudad y el personal del refugio para ayudar a las familias con la inscripción en la escuela, dijeron los funcionarios. El distrito también está tratando de atraer a más educadores bilingües y está dando prioridad a un mayor apoyo a las escuelas que tradicionalmente no han servido a los estudiantes de inglés, dijeron funcionarios.

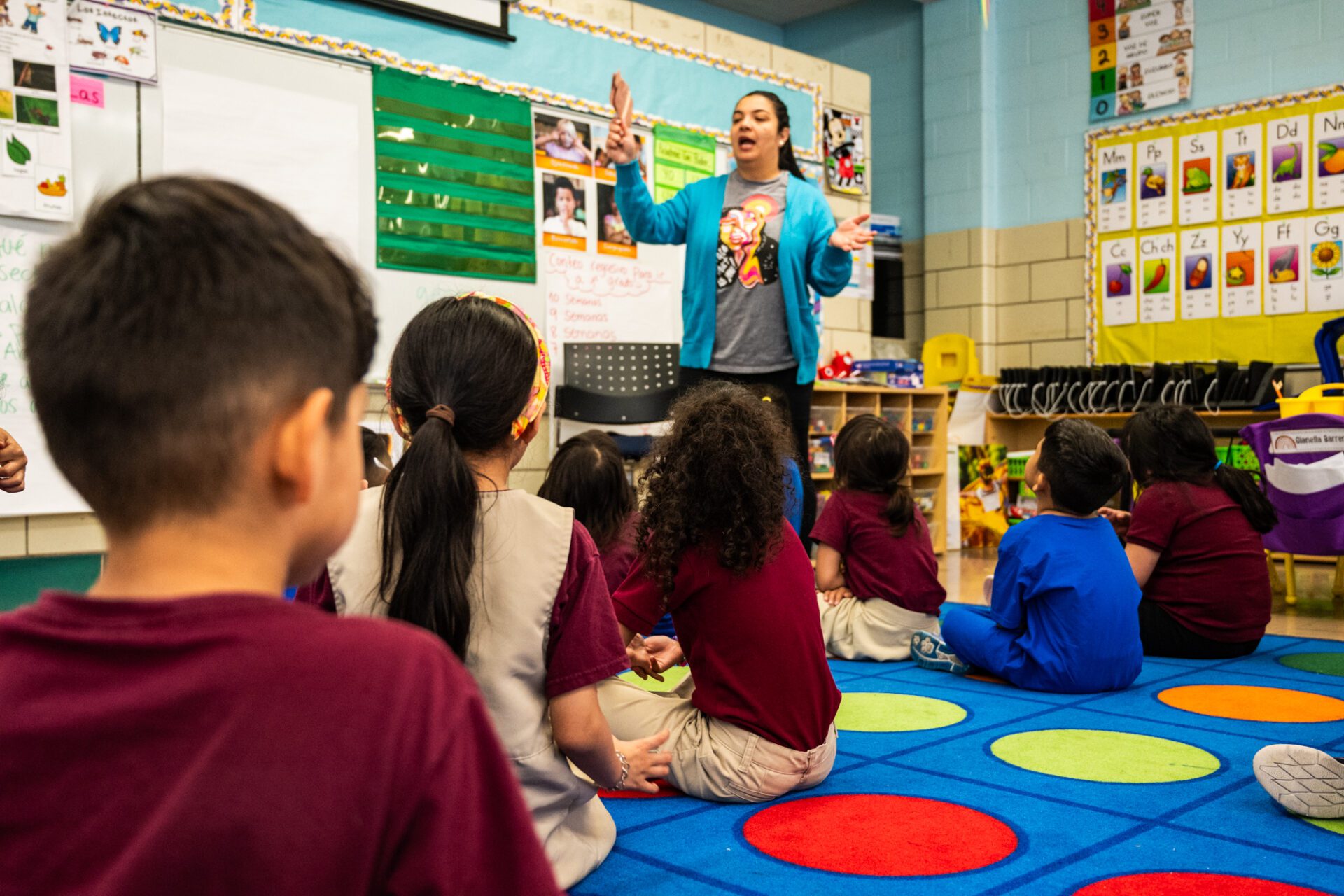

Pero los profesores dicen que los esfuerzos del distrito no se han traducido en más recursos sobre el terreno, y los niños inmigrantes se están perdiendo una instrucción vital. En la escuela primaria Laura S. Ward, en el West Side, que ha acogido a docenas de estudiantes de inglés, un profesor de preescolar y dos conserjes traducen para todo el edificio.

"Los dejaron en nuestra puerta, y se supone que debemos mantenerlo en movimiento, aceptar a estos niños, educarlos y mantenerlo en movimiento", dijo Dewanda Watt, maestra de primer grado en Ward, una de las docenas de escuelas que CPS identificó como carentes de suficiente personal para los aprendices de inglés.

"Debería haber habido un plan. No había ningún plan de las Escuelas Públicas de Chicago".

Las familias inmigrantes se reasientan en los lados Sur y Oeste

Como muchos emigrantes, Gabriela y su familia se marcharon de Venezuela a Chicago en octubre para huir de la agitación socioeconómica y política del país, dijo la madre de Gabriela, Yennifer Ruiz.

La familia vivió en la comisaría de Englewood durante unos meses antes de trasladarse a un albergue en Little Village, un barrio históricamente mexicano. Ruiz matriculó a su hijo y a su hija en escuelas con personal hispanohablante: Eli Whitney Elementary School y Richards Career Academy.

Pero cuando la familia se mudó a unos 13 kilómetros al sureste, a un apartamento en South Shore, Ruiz decidió cambiar a su hija al O'Keeffe, un colegio de mayoría negra y bajos ingresos que carece de recursos bilingües pero que estaba cerca de casa.

Como los Ruizes, una de cada diez familias solicitantes de asilo ha recalado en la zona de South Shore a través de un programa estatal de reasentamiento llamado Programa de Ayuda de Emergencia al Alquiler para Solicitantes de Asilosegún datos obtenidos por Block Club y Chalkbeat.

Dirigido por la Autoridad de Desarrollo de la Vivienda de Illinois y el Departamento de Servicios Humanos de Illinois, en colaboración con Caridades Católicas, el programa de ayuda al alquiler cubre tres meses de alquiler para las personas que emigran desde la frontera sur, solicitan asilo y llegaron a los refugios de la ciudad antes del 17 de noviembre de 2023. Es la principal estrategia de la ciudad para conseguir que las familias tengan una vivienda permanente una vez que abandonan los refugios.

Los datos muestran que casi el 60% de las aproximadamente 5.000 familias que utilizan el programa para reasentarse en Chicago encuentran vivienda en comunidades predominantemente negras y de bajos ingresos de los barrios sur y oeste. barrios históricamente desatendidos con escuelas que no atienden a muchos estudiantes de inglés y a menudo no cuentan con personal certificado para enseñar a esos alumnos.

A través del programa estatal, las familias pueden elegir dónde vivir, y "en última instancia, el bajo coste del alquiler es lo que impulsa la selección", dijo Daisy Contreras, portavoz del Departamento de Servicios Humanos de Illinois.

Legislación estatal exige a las escuelas que pongan en marcha programas bilingües -enseñanza en inglés y en la lengua materna del niño- cuando matriculen a 20 o más estudiantes de inglés que hablen la misma lengua materna. Las escuelas también deben enseñar a los alumnos la historia y la cultura de su país de origen.

Pero a medida que las familias abandonan los refugios y encuentran vivienda en barrios segregados y relativamente baratos, se encuentran con escuelas segregadas que sufren años de descenso de matriculaciones y recursos inadecuados, y mucho menos programas bilingües dotados de todo el personal necesario.

Este fue el caso de Nathaly García cuando recientemente se mudó de un albergue del centro de la ciudad a un apartamento de tres habitaciones en South Shore con el alquiler cubierto por el programa estatal. Su hijo de 11 años, Santiago, se había matriculado en la Ogden International School de Gold Coast y el traslado suponía triplicar el tiempo de desplazamiento.

Pero García no quería matricular a su hijo en la escuela cercana al nuevo piso porque había oído hablar mal de ella y consideraba que los resultados de los exámenes de lectura y matemáticas de la escuela no eran lo suficientemente altos, dijo.

Incluso después de que las familias abandonen los albergues, sus hijos tienen derecho legal a permanecer en la escuela en la que se matricularon originalmente porque las directrices del distrito clasifican a esos estudiantes como personas sin hogar, lo que les proporciona ciertas protecciones federales.

Así que García y su hijo ahora tomar dos autobuses una hora y media en cada sentido para continuar en Ogden. García dijo que nadie les dijo que podría solicitar el servicio de autobús amarillo.

En el caso de Yennifer Ruiz, nadie le explicó que su hija tenía derecho legal a permanecer en Eli Whitney, la escuela a la que iba la niña cuando vivían en el centro de acogida de Little Village, dijo. De hecho, cuando Ruiz mostró al personal de Eli Whitney dónde se iba a trasladar, le dijeron que estaría "demasiado lejos" de los límites de asistencia, dijo.

Los funcionarios del distrito dijeron ayudan a las familias a matricularse o trasladarse a otras escuelas que no están en su barrio, pero que pueden tener mejores recursos, como programas bilingües. Asaf dijo que las familias inmigrantes, como todas las familias de Chicago, pueden elegir dónde enviar a sus hijos a la escuela.

"Son residentes individuales e independientes de la ciudad", dijo Asaf, y añadió que el distrito se pone en contacto con los directores "en cuanto oímos llamadas de apoyo de las escuelas".

El director de O'Keeffe ha solicitado ayuda al distrito, y Gabriela ha empezado recientemente a aprender inglés a través de un programa extraescolar, dijo Ruiz.

El portavoz del distrito escolar dijo que O'Keeffe inscribió recientemente suficientes estudiantes de inglés para justificar un programa bilingüe, y la escuela ha sido aprobada para contratar a un profesor a tiempo parcial para trabajar con esos estudiantes.

Aún así, Yennifer Ruiz está ahorrando para que la familia pueda mudarse fuera del barrio y más cerca de una escuela que atienda mejor a su hija, dijo.

Tenemos que construir un programa desde la base

La escuela primaria Ward está en West Humboldt Park, un barrio con viviendas asequibles y con un elevado número de delitos relacionados con drogas y armas. Casi todos los alumnos de la escuela son negros y proceden de familias con bajos ingresos.

Los datos muestran que casi 140 familias se han reasentado en la zona de Humboldt Park gracias al programa estatal.

Tras años de descenso de la matrícula, las cifras de Ward se estabilizaron este curso escolar, ya que las familias inmigrantes encontraron apartamentos cerca de la escuela, dijo Watt, el profesor de primer grado de la escuela.

Watt tiene ahora nueve nuevos alumnos de Venezuela y Ecuador. Pero, como otros adultos de Ward, no habla español. La escuela primaria tiene docenas de estudiantes de inglés, pero sin profesores bilingües ni programa bilingüe, según Watt y los datos preliminares de matriculación.

Es una situación "abrumadora", dice Watt. Antes de este año, Watt, profesora desde hace 25 años, nunca había dado clase a alumnos de habla no inglesa.

Una auditoría de CPS de Ward en abril pasado encontró que la escuela, que tenía alrededor de 20 estudiantes de inglés en el momento, no estaba proporcionando la instrucción requerida a todos los niños que aprenden inglés y carecía de suficiente personal certificado, según documentos obtenidos por Chalkbeat y Block Club.

Ward es una de las 72 escuelas K-12 que CPS identificó con vacantes de personal certificado para enseñar ESL o clases bilingües en abril, según datos del distrito. Eso excluye la Academia Virtual del distrito. Una certificación de ESL no significa que el maestro habla otro idioma - sólo que están certificados para enseñar clases de ESL.

Según un análisis de los datos preliminares de matriculación realizado por Chalkbeat y Block Club, el número de estudiantes de inglés ha aumentado una media de más del 40% este curso escolar.

A principios de este año, Ward matriculó suficientes estudiantes de inglés como para justificar un programa bilingüe y ahora está trabajando para establecer uno, según un portavoz del distrito. La escuela fue aprobada en octubre para contratar una posición de maestro de medio tiempo para trabajar con aprendices de inglés y puede contratar para una posición de tiempo completo el próximo año ahora que la escuela ha matriculado a más de 50 aprendices de inglés, dijo un portavoz de CPS.

Actualmente en Ward, Watt y otros profesores confían en el personal hispanohablante que no tiene credenciales bilingües -el profesor de jardín de infancia y dos conserjes- para que les ayuden a comunicarse con los alumnos inmigrantes y las familias que buscan ayuda con las solicitudes escolares.

Durante un tiempo, la maestra de jardín de infancia tuvo que salir de su clase hasta cinco veces al día para traducir, dijo. El distrito proporcionó a los profesores dispositivos de traducción, pero los profesores de Ward afirman que no siempre funcionan correctamente y que no sustituyen a hablar el idioma.

La maestra de jardín de infancia, que no quiso ser identificada porque no estaba autorizada a hablar con la prensa, dijo que está dividida entre sus responsabilidades docentes y su trabajo no oficial como traductora de la escuela. Según Watt, algunos de sus alumnos inmigrantes progresan académicamente, pero otros tienen dificultades para entender sus tareas y aprender inglés.

"Algunos [profesores] están en colegios en los que el programa [bilingüe] ya está en marcha; simplemente lo continúan. A diferencia de nosotros, que tenemos que crear un programa desde la base", dice la maestra de jardín de infancia.

Asaf, la jefa de la Oficina de Educación Lingüística y Cultural del distrito, dijo que CPS ha estado abriendo puestos de enseñanza para las escuelas que están matriculando a muchos más estudiantes de inglés. Reconoció que la ayuda no puede venir de inmediato, y se necesita tiempo para construir programas bilingües.

"No siempre es fácil y no siempre es inmediato y no siempre es rápido", dijo Asaf. "Este es un distrito grande, y estamos constantemente prestando atención al número de [estudiantes de inglés] que tenemos".

Una historia de fracaso escolar para los alumnos bilingües

No es la primera vez que Chicago es objeto de escrutinio por la forma en que atiende a los alumnos que aprenden inglés.

En 1980, un decreto federal de consentimiento obligó a CPS a elaborar un plan para eliminar la segregación en las escuelas y garantizar que los estudiantes de inglés recibieran el apoyo adecuado. El decreto tuvo que actualizarse dos veces, en parte porque el distrito no conseguía proporcionar suficiente personal y materiales para los alumnos de inglés.

Los centros escolares son responsables de examinar a sus alumnos para determinar cuáles de ellos están aprendiendo inglés como nueva lengua. Esos alumnos tienen derecho por ley a recibir apoyo adicional, como enseñanza especializada de inglés.

Además de los requisitos estatales para los programas bilingües, las escuelas con 19 o menos estudiantes de inglés deben tener un programa conocido como Punto de Instrucción Transicional, que enseña a los estudiantes en inglés. No está claro cuántas escuelas de CPS están ahora obligadas a tener programas bilingües pero todavía no los tienen.

La segregación puede desempeñar un papel importante a la hora de decidir si los centros escolares ofrecen apoyo bilingüe a los alumnos.

Los inmigrantes de Chicago siempre se han asentado en barrios con personas que comparten su etnia o lengua materna, afirma Jim Lewis, especialista en investigación del Instituto de Grandes Ciudades de la Universidad de Illinois en Chicago, que ha estudiado la segregación.

Pero algunos de los recién llegados latinoamericanos a Chicago, como los venezolanos, no tienen enclaves, dijo Lewis. Además, muchos barrios históricamente latinos se han vuelto inasequibles para las familias que no tienen unos ingresos estables, lo que puede empujar a los recién llegados de hoy a barrios segregados que han sido ignorados durante mucho tiempo.

Para obtener un apartamento en el marco del programa estatal, las familias tienen que encontrar un propietario que participe en el programa o conseguir uno a través de Caridades Católicas. La única condición es que el alquiler sea asequible, dijo Emily Dagostino, portavoz de Catholic Charities.

Caridades Católicas no participa en el proceso de matriculación escolar, dijo Dagostino.

Funcionarios del distrito dijeron que CPS trabaja con el Departamento de Servicios Familiares y de Apoyo de la ciudad, albergues y directores para ayudar a las familias a matricularse en la escuela, y Asaf, el jefe de la Oficina de Educación Lingüística y Cultural del distrito, hizo hincapié en que las familias tienen opciones.

Pero la práctica del distrito de ayudar a las familias a matricularse en escuelas fuera de sus barrios no "sigue el espíritu" de lo que CPS dice que pretende ofrecer: igualdad de acceso a las escuelas de calidad del barrio, dijo Jesse Ruiz, ex director general interino de CPS y vicepresidente de la Junta de Educación de Chicago.

Ruiz lideró el encargo de auditar todos los programas bilingües y de ESL del distrito en 2015. Ese año escolar, el 71% de los centros auditados incumplían gravemente los requisitos estatales en materia de educación bilingüe. Chicago Reporter encontró en su momento.

Los problemas han persistido.

Durante el año escolar 2021 - antes de que los autobuses de Texas comenzaran a llegar - la Junta de Educación del Estado de Illinois puso a CPS en lo que se llama un "plan de acción correctiva" después de que los funcionarios determinaron que el distrito estaba fuera de conformidad con requisitos de educación bilingüe, dijo Lindsay Record, portavoz de la junta.

En una visita de seguimiento el año pasado, el Estado constató varias mejoras. Pero el distrito seguía sin tener programas bilingües en todas las escuelas que debían tenerlos, ni suficientes profesores titulados, según los documentos del plan de acción correctiva.

Ruiz, también ex presidente de la Junta de Educación del Estado de Illinois, dice que entiende por qué las escuelas con menos recursos no han tenido programas bilingües si históricamente no han atendido a estudiantes de inglés.

"Pero ahora tienen estos estudiantes, y eso es lo que dice la ley, que tienes que proporcionar servicios de educación bilingüe a esos estudiantes", dijo Ruiz. "El distrito va a tener que proporcionar esos recursos".

Fue un largo viaje

María, una inmigrante venezolana que llegó a Chicago el verano pasado, se mudó este febrero de un albergue del centro de la ciudad a un apartamento en South Shore gracias al programa estatal de ayuda al alquiler. Block Club y Chalkbeat utilizan un seudónimo para María por temor a la seguridad de su familia.

Tras la mudanza, la familia tuvo problemas para matricular a su hija de 8 años en la escuela. La primera escuela advertía que carecía de personal bilingüe, y en la segunda les rechazaron por vivir fuera de los límites de asistencia, cuenta María.

Desesperada por encontrar otra opción, la familia de María pidió ayuda a la Centro de Bienvenida del Instituto Clementedonde un empleado les indicó el Erie Elementary Charter School, un centro de enseñanza bilingüe situado en Humboldt Park, a 90 minutos en transporte público de su apartamento de South Shore.

El largo viaje a Erie no fue fácil, pero María dice que mereció la pena porque su hija aprendía más inglés y "entablaba conversaciones". Su hija dejó Erie hace poco, cuando la familia se trasladó a las afueras.

Muchos de los 49 alumnos recién llegados a Erie proceden de toda la ciudad, explica Carlos Pérez, director ejecutivo de la escuela.

Erie está mejor equipada que otras escuelas para atender a los hispanohablantes nativos que aprenden inglés. Como una de las 43 escuelas bilingües de la ciudad, Erie imparte clases en español e inglés a estudiantes de inglés y a hablantes nativos de inglés. Ocho de los profesores de Erie proceden de países latinoamericanos, según Pérez.

"Muchos de ellos han recorrido un largo camino para llegar hasta nosotros. Este era su objetivo: traer a sus hijos a una escuela en Estados Unidos... Hay un peso y una responsabilidad que vienen con ello", dijo Pérez.

Incluso con esos recursos, los profesores se enfrentan a grandes retos. La mayoría de los estudiantes migrantes llegan a Erie con más de dos grados de retraso, y algunos no han asistido a la escuela formal hasta por dos años, dijo Pérez. En 2022, Erie no cumplía con los requisitos del programa bilingüe y ESL, según la auditoría más reciente de CPS.

Varios directores cuestionaron la eficacia de las auditorías. Pérez dijo que un maestro que consideran eficaz no está certificado para enseñar a los estudiantes de inglés - una de las razones por las que la escuela está fuera de cumplimiento.

"A¿tenemos como objetivo el cumplimiento de las normas, o queremos poner delante de los estudiantes a buenas personas que puedan educarles?". dijo Pérez. "A menudo no son cosas intercambiables.“

Según CPS, cuenta con unos 7.500 profesores certificados para impartir clases bilingües, ESL o ambas, una cifra que ha crecido en los últimos años. Muchos profesores certificados para impartir esas clases ocupan puestos docentes ordinarios, dijo un portavoz.

Funcionarios del distrito dijeron que han tratado de atraer a más profesores bilingües mediante la subvención de los costes de la obtención de bilingüe o ESL endosos y la ampliación de las ofertas de trabajo temprano a los maestros que están completando sus requisitos. Pero es difícil cubrir puestos de enseñanza a mitad de año, dijo Ben Felton, jefe de talento del distrito.

Felton dijo que "simplemente no tenemos el talento" para que todas las escuelas tengan grandes programas bilingües "porque históricamente no ha habido tantos estudiantes bilingües en estas escuelas."

Un niño prospera, otro está "simplemente atascado

Aunque Yennifer Ruiz cambió a Gabriela de colegio tras mudarse a South Shore, optó por mantener a su hijo Gabriel, de 16 años, en Richards Career Academy, que tiene un programa bilingüe.

Después de sólo cinco meses en Chicago, Ruiz dijo que ha visto cómo esos recursos bilingües han ayudado a Gabriel a prosperar - está aprendiendo inglés rápidamente e incluso se ha unido al equipo de béisbol de la escuela - y cómo la falta de servicios ha hecho que Gabriela se sienta perdida en la escuela.

Gabriela desearía poder volver a Eli Whitney, donde le gustaba poder comunicarse con sus profesores y otros niños, dice.

"Me siento muy mal porque todo el objetivo de mudarme aquí era conseguir calidad de vida", dijo Ruiz en español a través de un traductor. "Sé cómo mi hijo está sacando su máximo potencial, pero ella está estancada".

Ias entrevistas con hispanohablantes se realizaron con la ayuda en la traducción de Yoha Salmeron Chaparro, becaria del Centro de Acompañamiento a Inmigrantes y Refugiados de la Universidad de Loyola, y Alex Hernandez, reportero de Block Club Chicago.

Reema Amin es reportera cubriendo las escuelas públicas de Chicago. Contacte a Reema en [email protected].

Mina Bloom es periodista de investigación de Block Club Chicago. Contacte con Mina en [email protected].