by Benjamin Giska. Jason Marck / WBEZ

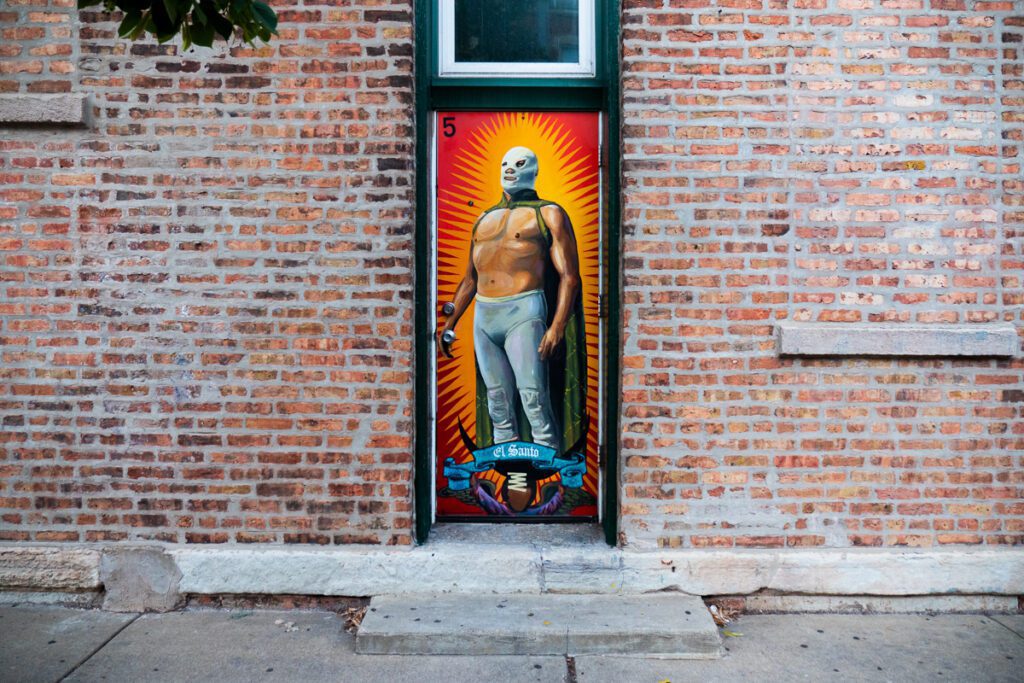

by Benjamin Giska. Jason Marck / WBEZDifferent artists have painted a series of murals on doors along 18th Street, inspired by the classic Lotería game.

Pilsen has long been known for its murals featuring images of lost loved ones, Chicano history, anti-war movements and struggles for education and workers’ rights.

But since 2016, a series of doors painted with images inspired by the classic Mexican game of chance called Lotería has popped up along 18th Street. And while the series of nine doors includes some traditional images from the game, like the ladder that accompanies the card La Escalera, other doors feature creative riffs on classic Lotería images, like the luchador El Santo.

El Santo, located just off 18th Street, was commissioned by Rick Garza and painted by Benjamin Giska. Maggie Sivit / WBEZ

Rick Garza came up with the concept for the doors and also funded the project. Garza isn’t the first to riff off imagery from the Lotería game but as he puts it, he’s “run with it.”

After traveling back and forth between the U.S. and Mexico for several years, Garza’s family settled in Chicago permanently in the 1960s, when he was around four years old. “So since 1964,” he said, “I’ve had a connection to Pilsen in one way or another.”

Today, Garza and his wife, Eiliana, run International Real Estate, a real estate company based on 18th Street.

In 2016, Garza said he became frustrated by graffiti and gang activity in the neighborhood and wanted to do something about it. So he began approaching artists whose work he’d seen, asking if they would be interested in painting the doors of some of the buildings near his office.

“It was mostly to combat gang graffiti, which was a problem on our doors,” Garza said. “The gangbanging culture was so thick. It was just a detriment to all the young people in the community,” he said.

Plus, said Garza, commissioning the paintings was a way to do something “nice for the heritage of the Mexican American community” — whose contributions, he added, are often overlooked.

Since the first door was painted in 2016, the project has grown to include nine doors all over the neighborhood on 18th Street, 17th Street, and Laflin Street. It’s also inspired several copycats, like La Dama on 18th Street, something that Garza said he’s encouraged.

“We asked people to keep imitating it and decorating their doors,” he said, because it helps give the community “more character.”

Young artists making a mark on Pilsen

Garza commissioned Rocio Urbano, a 35-year-old painter who grew up in Pilsen, to paint the door titled La Doña.

It depicts the image of María Félix, one of the most prominent actors in Latin American cinema during the 1940s and ’50s.

La Doña, located on Laflin Street, was painted by artist Rocio Urbano. Jason Marck / WBEZ

“She was one of the biggest, probably the first female who took over Mexican cinema,” said Urbano. “She played a huge role.”

Urbano said she was excited to paint Félix because of what the actress represents to young women. “I think that María Félix represents a lot of things that empower women,” said Urbano. “She was brave, and a lot of her roles had to do with fighting through patriarchy and oppression and rising to the top. And so that makes her a saint to me.” That’s why a halo appears around her head on the door design, Urbano said.

For Urbano, some of the most special parts of this project were the conversations she got to have with people from the neighborhood who came up to her while she was painting.

“All of these older people came out and were really excited and really happy to see something that they recognized from their era,” she said.

Urbano also said the project has given her the opportunity to be a part of the long tradition of mural painting in Pilsen.

“Growing up in this neighborhood, there’s always been art being painted in this neighborhood, since before I was even born,” she said. “So to be a part of that, in my own neighborhood, is really special. And I think to keep that tradition going is also really special, honestly. It’s the biggest honor to be able to do it. I never in a million years would have thought that I would be doing this.”

A long tradition of mural making

For Teresa Magaña, a Pilsen artist who is also executive director at Pilsen Arts and Community House, it’s important to think about murals like the Lotería doors in context.

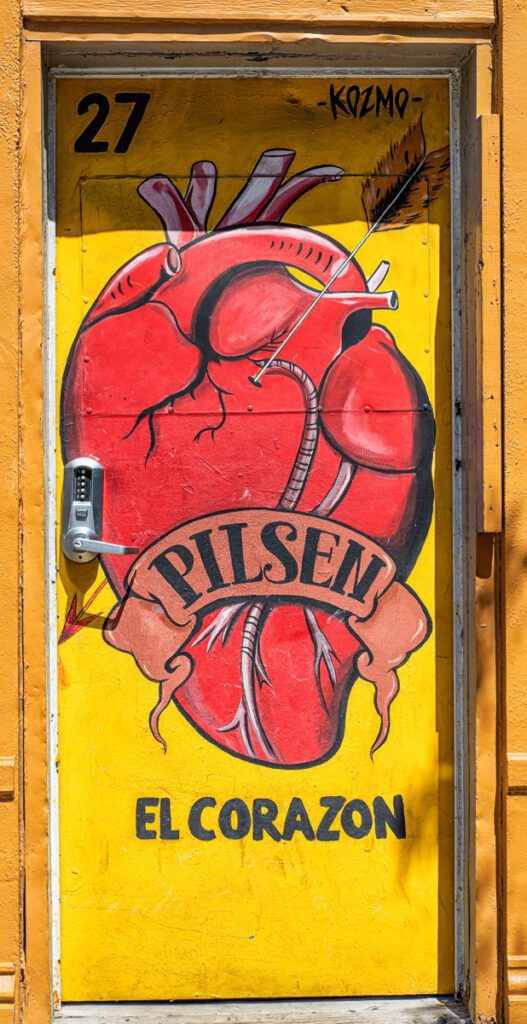

El Corazón on 18th Street by the artist KOZMO. Jason Marck / WBEZ

“I’m a little bit of the old-school, traditional belief that the purpose of murals is telling a story, being a voice for a mass of people that aren’t being heard. So the murals in Pilsen have served that — from the first generation that started doing those here in the ’70s, they were all very politically driven, really telling the story of the culture and the community that was being built here.”

For Magaña, who did not paint any of these murals, the Lotería doors may be part of a new wave of mural-making, but they still speak to a community that has deep roots here and is struggling to hold onto them.

“I think it’s interesting, because it definitely highlights the culture that’s still here,” Magaña said. “And I think as Pilsen’s changing all the time, it’s a reminder to any new residents that there is still this Latino culture, this Mexican culture here.”

Nevertheless, Magaña thinks it’s important for painters of public art to ask themselves questions about the impact that the work will have. Particularly in a neighborhood like Pilsen, where the struggle against gentrification is always top of mind.

“I think that as artists, we have to ask ourselves, when we’re doing artwork on a particular building, how that contributes [to a changing neighborhood] or not?” said Magaña. “Who’s going to benefit from viewing the art that you’re creating, and who is it really for?”

Who benefits from the murals?

Urbano, the artist behind La Doña, does not shy away from these questions.

La Sirena on 18th Street by the artist MATR. Jason Marck / WBEZ

“It’s interesting because the tradition of mural painting has been going on in Pilsen for [years and years],” Urbano said. “And so to say that these murals are contributing to [gentrification], then you’re saying that since the beginning of people painting in this neighborhood, they’ve been contributing to this. I’m all for helping defend families from being pushed out of the neighborhood. But it’s hard for me to agree that murals are contributing to that [displacement].”

Magaña, for her part, wants to attend to the nuances of different kinds of public artworks. Over the years she’s seen murals go up in Pilsen on new or rehabbed buildings, and they seem to have been commissioned for the sole purpose of cashing in on aesthetic appeal while increasing property values.

“That’s why I think it’s kind of a fine line,” said Magaña. “But I’ve also seen long-standing, local mom-and-pop shop businesses here that embrace the artist community and ask them, ‘Hey, can you help do this door? Can you help do this small mural on the side of my wall?’” For Magaña, these projects initiated by people who grew up in the neighborhood — and who are choosing, or fighting, to stay there — are important, even when the artworks themselves don’t appear political in content.

Magaña said she hopes the Lotería doors remain in Pilsen and other Mexican American neighborhoods. There’s a history, a context in these communities, she said, that helps give them their meaning.

Rick Garza, who came up with the idea for the Lotería murals, takes a slightly different view. He thinks they’ve been a good thing for Pilsen because they draw all kinds of people to the neighborhood — including tourists and the descendants of people who grew up there.

“Hopefully it [the project] will continue to grow throughout the community and maybe even the whole city,” he said.

Additional reporting for this story came from Leslie Hurtado and Monica Eng. Follow Leslie at @LessHurtMedia and Monica at @monicaeng

Thanks to María Inés Zamudio, Marie Mendoza and Linda Lutton for their help producing this episode. Listen to the full episode to hear more about the Lotería doors as well as answers to two other questions about Pilsen — including one about the history of Benito Juarez Community Academy and another about Pilsen’s sidewalks.