At least 8,372 Muslim Bosniaks were killed in the 1995 Srebrenica genocide when Bosnian Serb soldiers swept into a U.N.-designated “safe haven.” Šehović remembers the fear and horror that her family experienced at the time, emotions that she has channeled into her public monument to the genocide: ŠTO TE NEMA or “Why are you not here?”

At least 8,372 Muslim Bosniaks were killed in the 1995 Srebrenica genocide when Bosnian Serb soldiers swept into a U.N.-designated “safe haven.” The soldiers executed the men and boys who lived there and deported and abused between 25,000 and 30,000 women and elderly residents.

Aida Šehović was just a teenager when the genocide happened. Born in Banjaluka, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Šehović remembers the fear and horror that her family experienced at the time, emotions that she has channeled into her public monument to the genocide: ŠTO TE NEMA or “Why are you not here?”

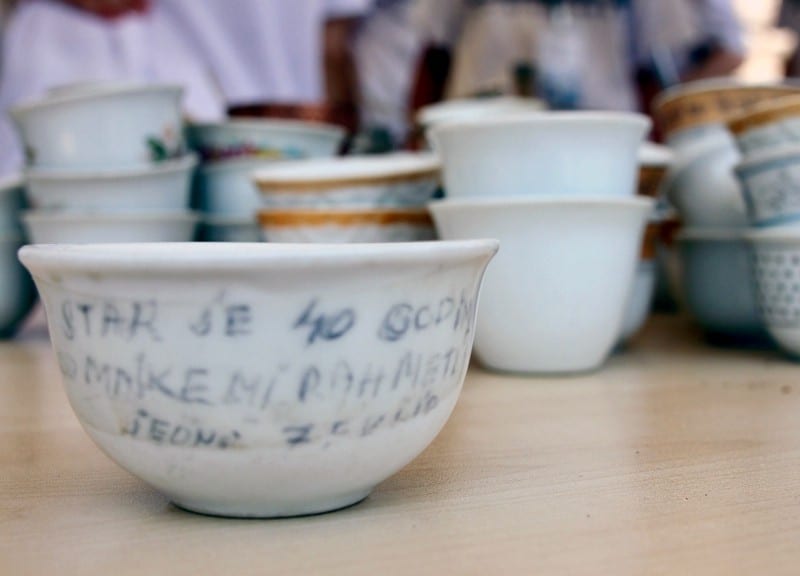

At its heart, ŠTO TE NEMA is about the physical rituals of loss, remembrance, and healing. Anyone who passes by is invited to assist in the assembly of 8,372 delicate fildžani — small porcelain coffee cups donated by Bosnian families around the world — that are then filled with strong Bosnian coffee. Their number roughly corresponds to the growing number of remains found, identified, and buried to date.

This year’s nomadic monument was set up in Chicago on July 11 for the anniversary of the genocide. Borderless sat down with Šehović to discuss the life of ŠTO TE NEMA and her experience advocating for genocide awareness.

I was fifteen when the war in Bosnia started, and I believe that has influenced my decision to become an artist more than anything else. My life was turned upside down and art allowed me to start processing everything that was happening. Fifteen is an interesting age because you are too young to understand what’s going on, but old enough to understand that something horrific is taking place.

The war opened up this whole other side of what it means to be human. It is something I’m grappling with or trying to understand to this day. How can something like this happen? How and why do humans become so violent toward each other? How can it happen on such an organized scale? People collectively deciding to do horrible things to each other. And most importantly, why is it that nobody seems to care? All of my artwork in one way or another goes back to these questions.

In 2004, a couple of years before ŠTO TE NEMA began, my family went back to Bosnia together for the first time, and that was quite an emotional and intense trip for all of us. I’m pretty sure that was also the first year, or first time that that the body remains from those killed in Srebrenica were collectively buried in Potočari.

I remember reading two stories that had a huge impact on me during this trip. One was by a survivor who was exactly my age. He was a young man who fell down during one of the mass executions, so that he was covered with other bodies. This is how he had survived. Because he and I shared the same birth year, I couldn’t stop thinking, “What if I had been born in Srebrenica? What would have happened to me?” It was so random that I happened to be born in one part of the country, Banjaluka, and he happened to be born in Srebrenica.

The other story I read was by a woman who talked about how much she still missed her husband. She talked about not having closure because she was still waiting to find his remains, which is also why she felt as if she was still waiting for him to return. And how much she missed him every day because she had nobody to drink coffee with. I connected to that immediately because I grew up watching my parents drink their morning and afternoon coffee together every day. Coffee is such a big aspect of our culture.

In 2006, I had an idea to do a one-time performance with fildžani and coffee about the aftermath of the Srebrenica genocide. I was a very young artist at the time, and this was right before I started graduate art school in New York. I wanted to do this performance in a public square in the heart of Sarajevo. My idea was to make Bosnian coffee on site and serve it into fildžani placed on the ground for the men from Srebrenica who would never come to drink it. Because so many families have been affected by the genocide, I thought from the beginning that it was very important that fildžani are collected and donated by others and not just me.

I reached out to an organization called “Women of Srebrenica” who supported my idea and collected 923 cups that I used during the first iteration of ŠTO TE NEMA. At the time, I really did not think past this initial idea of a one-time performance. I was too young to understand the effect it would have on people who were there with us that day (July 11th, 2006). Our team was very small: my cousin, her boyfriend, my American boyfriend, my aunt, and a few other relatives. They were making the coffee all day and helping with logistics while I was placing down fildžani, and filling them with coffee.

Once passersby realized what I was doing, everyone seemed to have such a visceral and emotional reaction that the word about my performance just kept spreading throughout the day. More and more people kept coming to the square, bringing me fildžani they wanted to contribute to ŠTO TE NEMA. That was also how I got the oldest fildžan ever donated to the monument. It’s a cup more than 40 years old from a woman from Sarajevo, not from Srebrenica. But she told me that she and her husband had lost two daughters during the siege of Sarajevo.

As overwhelming as that first performance was for me, it was clear that what I was doing, what we were doing, had a very powerful impact on people. The performance itself was perhaps not creating real change, but it stirred something up, it opened up a space. Until that moment, I don’t remember any other opportunities that allowed Bosnians to simply talk to each other about their losses and trauma, to share their experiences with each other, to mourn and heal collectively in a public space. The next year, my friends here in New York organized an exhibition at the United Nations headquarters that was based around the commemoration of the Srebrenica genocide, and they invited me to repeat the performance. So, I did, still not quite realizing that this would be a recurring work that I would make every year.

When we set up ŠTO TE NEMA for the third time, in third consecutive year, the performance became a participatory project. This was in Tuzla, Bosnia and quite special for me because the same women from Srebrenica, who helped me collect those first fildžani, and their children, could all be present. When I started placing the cups on the ground in Tuzla, they approached and said: “Let us help you.” And I thought to myself: “Oh, of course I’ll let them help me. We should be doing this together because all of this is for them.”

This organic evolution is exactly how ŠTO TE NEMA has been changing and growing over the years. What happened in Tuzla convinced me that we need to do this every year. That we should just keep adding more fildžani to the existing collection, so that the number of cups symbolically follows the number of body remains that have been found, identified, and buried to date.

Today, ŠTO TE NEMA has evolved into an annual nomadic monument that has traveled to 12 different cities during the past 12 years. By now, the monument has its own sort of myth or story; most information about it is still shared orally. People tell each other about it. They share stories about fildžani they collected and donated, or other ways in which they participated and contributed. It all began with the first 932 collected fildžani and this year the monument consisted of more than 7,500. So, the monument has grown in its size quite a bit. As has the organizing team behind it to accommodate a project of this scale.

Over time, my role has changed as well. I am now the caretaker of a nomadic monument that continues to grow. My job now also includes protecting everything that ŠTO TE NEMA represents. Of course, I need to always be respectful, first and foremost, toward survivors and their families. A lot of times, their experiences, their stories of their struggles and tremendous losses get used and misused for people’s personal agendas. I am aware of the potential to manipulate ŠTO TE NEMA and it is my job prevent that from happening.

I am also responsible for making sure that we continue moving forward. I want to make sure that ŠTO TE NEMA remains a monument that is open to everyone, and that we persist in trying to figure out how to make it even more inclusive and relevant for people who might not be connected to Srebrenica or Bosnia. Even though we are commemorating one specific genocide, this is truly about all genocides and what we can all do to change the current trajectory. This is why, for example, there are no signs, flags, or banners on the site where we construct the monument. This is an intentional and very important decision I’ve made by learning what works and doesn’t work in the past. I know from experience that using any kind of symbols is just another way for us to create a border between us, so eliminating those divisions is essential.

But every time I work with a new community we have to sort of relearn all of that together. I have to convince them that the monument is more effective if we don’t have any Bosnian flags. That it is more powerful if passersby don’t know what’s going on. If people just ask each other about the fildžani on the ground that are filled with coffee that nobody is drinking. So, instead of symbols and signs, we have trained volunteers on site who encourage conversations between visitors. People end up organically inviting each other to participate by filling the collected fildžani with coffee in memory of the victims who will never drink it. It is so important that we are all there first and foremost as humans, supporting and taking care of each other. This is also why I talk about ŠTO TE NEMA as our monument and not my monument.

Chicago has the second largest Bosnian community in the United States, but it is not necessarily unified because of its size. Certain divisions have existed for years, and different groups have different ways of doing things. Asja Dizdarević, who was my local project coordinator for Chicago, and I worked so hard to transcend those divisions and bring everyone together. Many of our partner groups and organizations collaborated for the first time. Once the results of that transformation started manifesting itself, it was so exciting for everyone involved.

Personally, I was very grateful to have worked with survivor families from Srebrenica who are Chicago residents. Some of the men among them had survived the “March of Death” through the woods and mountains, which was actually a trap and how the men and boys were killed. The Association of the Srebrenica survivors in Chicago had organized the transportation of all the fildžani from Boston, the city that hosted ŠTO TE NEMA in 2016, to Chicago and helped us with all the preparations. Most of them went back to Bosnia for the mass burial in July so they couldn’t be with us at Daley Plaza on July 11th, but several other families from Srebrenica joined us.

Six of the volunteers on our team are children of the survivors, and that was very special for them and all of us who were part of our team. They’ve lost most of their male family members and relatives. To create a space for them where they could talk about this in a way that’s also simultaneously healing while they are mourning is one of the main reasons why I continue to make this work.

Overall, we had over 100 volunteers during the whole day who came at different times and helped, so this was the largest iteration of the monument in many aspects. Some of them were making coffee throughout the day or helping with logistics around that. But the majority of them were engaging the public. They were dressed in plain clothes and not easily identified so that nobody actually knew who had the information about what was going on. This was done in order to encourage people to just ask the nearest person, “Hey, do you know what this is?”

When I train the volunteers I do not give them any prescribed information about the monument. I do not think it’s interesting for them to just recite facts about genocide or Srebrenica. This is how we normally receive this information — in a way that we cannot relate to. Instead, we work together so that each one of them can find their own language. We are all learning in the process and trying to figure it out together: How do we talk about genocide? How do we educate others? How do we heal together?

I’m not sure that we have found a proper language that allows us to process the violence of genocide as humans. We have legal language, but how do we have a conversation with somebody who has lost 20 family members, for example? Or with somebody who cares but is not directly impacted by any of it? Or even with a five-year-old kid who wants to help and be part of the commemoration? Or with somebody who doesn’t seem to care at all?

We usually talk about the victims, those who were systematically killed, as if they were just numbers and not actual human lives. I don’t have an answer, but ŠTO TE NEMA gives us an opportunity to ask these questions. I believe genocides continue to this day because we are too afraid to really look at what it is or too uncomfortable to confront it. Genocides are one of the most developed forms of human oppression, they are so horrific that a wall just goes up.

After the Holocaust we collectively said “never again,” yet the Bosnian genocide took place a little more than 50 years later in the heart of Europe. There is a genocide taking place right now. Raising genocide awareness is a very important aspect of ŠTO TE NEMA. By creating a personal relationship for every person who walks by it, my hope is that then they will never think of Srebrenica — or any genocide — in the same way again. There is a difference when people are just exposed to this information, feeling that there is nothing they can do, versus having the opportunity to perform a gesture of remembrance — as symbolic as that might be. Once somebody has held the cup that represents one person who is no longer here in their hand, once they have placed it down on the ground, filled with coffee honoring that person, they are directly connected to Srebrenica and that history. For a moment, they feel that they have agency and a role in all of this.

I really believe that art can change the world — but it can’t fix it. Art can inspire. ŠTO TE NEMA is not about creating laws, and we won’t stop genocide directly. But I’m hoping that if we touch enough people, if we make them feel that together we can make a difference, perhaps then we will continue finding better ways of grappling with genocides. Especially today in this world where we actually have real-time information when atrocities taking place. We know what happens, when and where. There is truly no excuse for us as humans to allow this to go on.

I feel that if we can’t prevent genocides — one of the most extreme forms of violence — how can we ever imagine a world without violence at all?