Claudia Hernández/Borderless Magazine

Claudia Hernández/Borderless MagazineCheaper medicine and doctor visits have drawn Mexican-Americans to Ciudad Juárez during the pandemic, despite concerns about COVID.

Waiting in line at the Cordova Bridge to cross from El Paso, Texas to Ciudad Juárez, Mexico and back is an everyday act for many Mexicans and Americans living along the Mexico-U.S. border. The bridge is often congested with cars as people wait up to four hours to cross to go to work, visit family, shop or see their doctor.

News that puts power under the spotlight and communities at the center.

Sign up for our free newsletter and get updates twice a week.

Over 29 million people cross between Ciudad Juárez and El Paso every year, with people coming from as far as Chicago to visit Mexico. During the escalating coronavirus pandemic that has many experts concerned.

Neither the U.S. nor Mexico require any health checks in order to enter each other’s country at the border crossing. While for a time Mexican authorities were taking the temperatures of people who crossed the border in order to curb the spread of the virus, they no longer are doing so.

Today, both El Paso and Ciudad Juárez are COVID-19 hotspots. Both cities are under lockdown and El Paso has the second highest COVID-19 infection rate in the United States. As of October 20, Ciudad Juárez has 10,043 active COVID-19 cases and 992 COVID-related deaths while El Paso has 8,350 active cases and 557 deaths.

To help slow the spread of the virus, the U.S. has restricted border access since March by barring non-U.S. citizens, non-permanent residents and people without a letter from their employer from crossing the border. They have also discouraged people who are allowed to cross from doing so in order to help slow the spread of the virus. On Monday, the head of Ciudad Juárez’s local government asked his country to work with the United States to bar non-Mexican citizens from crossing the border as well.

Read More of Our Coverage

non-Mexican citizens from crossing the border as well.

“Considering that El Paso is one of the cities with the highest number of infections in the entire United States, I am requesting the corresponding authorities to evaluate the restriction of North American visitors for non-essential matters,” Ciudad Juárez Municipal President Armando Cabada Alvídrez said.

Yet for many of the people most impacted by COVID-19 in El Paso crossing the border is a necessity. With health care costs dramatically different in the two countries, each day people from the United States wait hours to cross the border to get tested for COVID-19, purchase medicine or even get hospitalized.

‘We all had COVID at the same time’

Valeria Terrazas is a 27-year-old American citizen who works in El Paso but lives in Ciudad Juárez with her parents. She works full-time and is in charge of getting groceries and other essential items for the household. When the border restrictions began earlier this year, Terrazas continued to cross between Ciudad Juárez and El Paso border to go to work.

On the morning of July 14 she woke up at her home in Ciudad Juárez feeling light-headed and decided to get a COVID-19 test in El Paso. Two days later her test results came back positive.

“I barely had any symptoms. I had a little bit of fever and a headache, but I just took some aspirins. The day I started to feel better is when I found out I had COVID. That same day I noticed I lost my sense of smell and taste,” Terrazas said.

Terrazas self-isolated in her bedroom and continued working from home, but she feared her parents could get infected since they shared a home. Her father, Raul Terrazas, has thrombocytopenia and hypertension, which puts him at high risk for severe infection. Four days after Valeria started feeling sick, her parents began showing symptoms of COVID-19 as well. Her father was initially reluctant to get tested for the virus, but when he couldn’t continue his normal routine he agreed to take the test.

“We all had COVID at the same time. The bright side was that I no longer had to be isolated in my room because everybody else already had it as well,” Terrazas said.

The family stayed at home and waited until they all tested negative for the virus, Terrazas said.

“My parents wanted to blame me because I was the one going out of the house. But then everyone [else in my family] started getting sick,” Terrazas said.

Despite the stay-at-home order, Terrazas’ aunts, uncles and cousins who don’t live with her and her parents continued seeing each other. The CDC has warned family gatherings put people at increased risk of COVID-19 infection and such gatherings have driven a surge in COVID cases in places like Chicago.

Terrazas’ extended family got together for a July 10 dinner party and three days later eight family members started showing symptoms.

“It turns out I wasn’t the first one who got sick. My aunt was. And she was the one who got the worst symptoms,” Terrazas said.

Eight people from the Terrazas family tested positive for COVID-19. Her aunt was hospitalized in Ciudad Juárez. Four of them were prescribed Jakavi, also known as Ruxolitinib, a drug typically used to treat high-risk myelofibrosis — an uncommon type of bone marrow cancer. The price for a dose of the drug in Mexico averages around $2,000 USD.

“We were shocked because it is so expensive. Luckily I didn’t have to take any expensive medicines. I was so lucky,” Terrazas said.

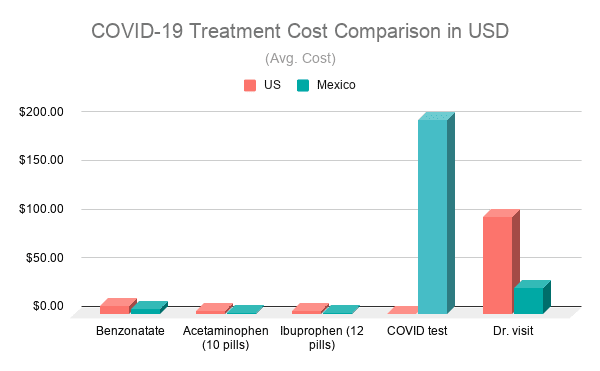

A Borderless Magazine survey of health care providers and pharmacies in both El Paso and Ciudad Juárez found dramatic differences in health care costs between them. While people can get tested for COVID-19 in El Paso for free thanks to a city order, the same test just blocks to the south in Juárez costs between $60 to $200.

And while a prescription-strength cough medicine like Benzonatate — which is frequently used to treat COVID-19 symptoms — costs an average of $9 in El Paso, it only costs an average of $5.60 in Ciudad Juárez, where it can be purchased over the counter.

Terrazas and her family bought all their medicine in Ciudad Juárez after they started comparing prices with what was available in El Paso.

Two weeks later, Valeria’s COVID test came back negative and she was able to get back to work. She and her parents had mild symptoms, and the three of them were able to go back to their pre-COVID routine.

“We were all very lucky. It was actually nice to stay at home together. We really bonded,” Terrazas said.

‘It Is Hard Not Imagining The Worst’

Brenda Rubio, 23, is an American citizen who lives with her parents in El Paso where she also works as the front desk receptionist at a local pediatric dental clinic on Mesa Street. She contracted COVID-19 from her parents, Ana Moctezuma and Jorge Rubio, who in turn got it from a family member who visited their home.

Rubio says her parents kept visiting family members despite the city’s stay-at-home order.

“My mom was still a little bit skeptical about COVID-19, she kept going out of the house. I didn’t go out at all. But we live together so I would see her and my father every day,” Rubio said.

Rubio’s mother was the first one to get sick. She had severe complications from the infection because she suffers from asthma.

Rubio’s parents initially considered going to a hospital in Ciudad Juárez for cheaper COVID treatment. Mexican citizens enrolled in Ciudad Juárez’s public healthcare program can typically receive hospital treatment for free. Meanwhile, staying at a hospital in El Paso can cost an average of $4,000 per day.

Despite the potential to save money, after some research Rubio realized the hospitals south of the border were overcrowded and decided it was probably best to seek treatment in El Paso. Her mother spent three days at the hospital and despite doctors releasing her to go home, she continued to get worse.

“My dad was the next one to get COVID. He was the one who was taking care of my mom at all times. He had fever for five days before he even considered going to the hospital,” Rubio said.

Rubio’s father was also hospitalized in El Paso and was there for five days. Doctors diagnosed him with both pneumonia and COVID-19.

“It is hard handling a situation like this one. It is hard not imagining the worst. When I drove my parents to the hospital I didn’t really know if it was the last time I would see them,” Rubio said. “I’ve heard so many stories about people who didn’t even have the chance to say goodbye to their loved ones. I was so scared.”

Rubio’s mother ended up spending three days in the hospital, while her father spent five days there. When they were released, they received a bill from the hospital for $2,500.

“I was shocked, I thought we were going to have to pay way more. When we called and tried to pay, they told us we didn’t have to worry about it. It turns out the State of Texas paid the bill [through the CARES Act] because my parents were in the hospital due to COVID,” Rubio said.

Once they were released from the hospital Rubio was the only one caring for her parents. They were quarantined for a month at home by orders from the El Paso Health Department. Health officials would check in every day on the family’s status.

“We would order groceries on Walmart delivery and our friends would help us buy medicine,” Rubio said.

The family’s El Paso doctors prescribed her parents some medicines like Benzonatate. Altogether, the medications the doctor prescribed for her parents ended up costing a total of $60. When these prescriptions ran out, Rubio sought cheaper COVID treatment in Mexico. She asked a friend to buy her the same medicines but in Ciudad Juárez so she wouldn’t have to pay the doctors in El Paso to get a prescription again.

One week after her parents started feeling better on May 25, Rubio got COVID-19.

“It was a good thing that I got it a few days later than my parents because they didn’t need me to take care of them anymore. It would have been awful for the three of us to be in bed at the same time,” she said.

Rubio suffered from symptoms for six days, but she didn’t need to visit the hospital.

Choosing Between a Healthy Life or Life Without Debt

While this year has seen an increase in American patients seeking medical care in Mexico, the phenomenon didn’t start with the current coronavirus pandemic.

Jesús Rivera is a 64-year-old general practitioner in Ciudad Juárez. For four years he worked at a Benavides Pharmacy in Ciudad Juárez, where he treated many patients who came from the United States, including places like Chicago.

“A lot of them came not only from El Paso, but also from northern parts of the United States,” Rivera said. “The healthcare system in the United States is very overpriced and inefficient. I guess that’s why they cross the border to get medical assistance.”

Most of his American patients didn’t have medical insurance in the United States, and they came to him to get more affordable care. Rivera now works as a doctor at a factory, but he still receives calls from his former patients living in the United States asking for his help.

“Our border life consists of purchasing certain things that are cheaper in the U.S., and other things in Mexico,” Rivera explained. “Medicine is definitely cheaper here [in Mexico]. Especially now with the pandemic, people are more desperate to save money.”

Researchers have reported evidence that patented brand name medications in some other countries tend to be 28 to 42 percent cheaper than the ones being sold in the United States.

So while testing for COVID-19 is more expensive in Ciudad Juárez, a visit to a doctor can be up to ten times cheaper than in the U.S. And in addition to medicines costing less, many of them which are only available for purchase with a prescription in El Paso can be easily bought without one in Ciudad Juárez.

But the rush of people seeking medicine without a doctor’s prescription in Mexico is causing other problems, according to a joint study by the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services and the University of Pennsylvania.

“In some cases, the ability to purchase brand name drugs without prescriptions may be causing inventories to be depleted in Juárez,” the study’s authors wrote.

And cheaper COVID treatment is only the most recent cause of medical tourism to Ciudad Juárez. Out of 1,000 people interviewed from both sides of the border, over one-third of adult residents of El Paso reported crossing into Ciudad Juárez to buy medications, according to another study published by the Journal of the National Medical Association in 2009.

A lack of access to health insurance in the United States was cited as one reason Americans cross into Mexico to buy medications and seek dental and other medical care, the authors wrote.

“Medical assistance is basically free in Mexico, and Americans take advantage of that.” Rivera said.

Both Terrazas and Rubio were quarantined around the same time; Terrazas in Ciudad Juárez and Rubio in El Paso. A disease that could have cost them a fortune ended up being an affordable bill. But for Rivera, the fact that both women had to consider the price of healthcare at all while being sick with the coronavirus and caring for their families is heartbreaking.

“People shouldn’t have to choose between living a healthy life or a life without debt,” Rivera said. “I guess I wouldn’t have had as many patients if it wasn’t for the people who cross the border, but I can’t imagine what it must be like going through all that trouble just to be healthy. Mexico may not be the best country in many aspects, but at least people here have access to free healthcare.”

Editor’s note: All monetary amounts in this article are USD.