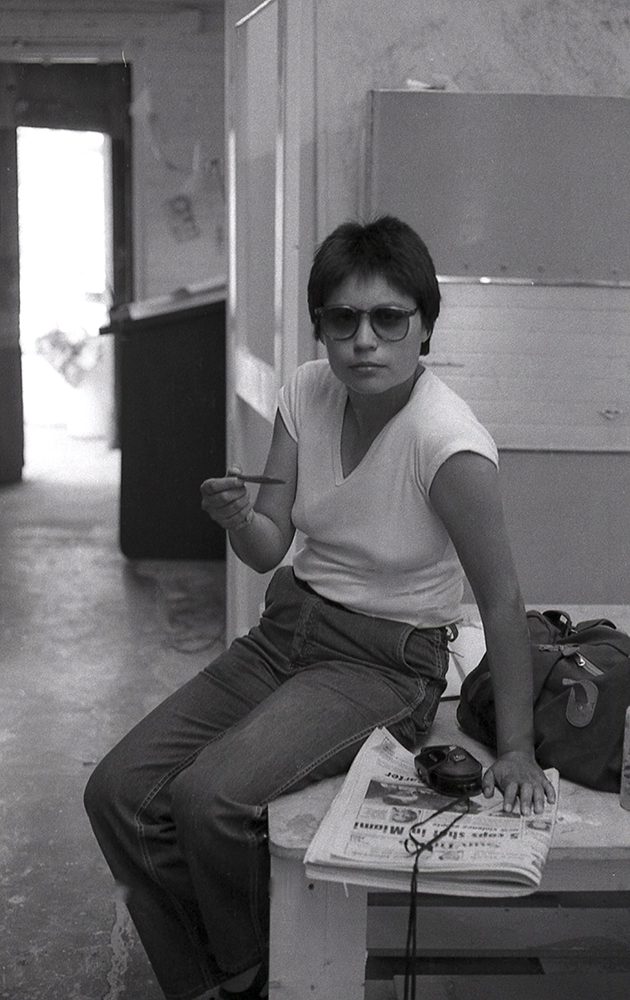

Jonathan Aguilar/Borderless Magazine

Jonathan Aguilar/Borderless MagazineThe longtime Pilsen resident will release a new, bilingual photography book this fall.

During the coronavirus pandemic, longtime Pilsen resident Diana Solís started taking long, early morning walks through her neighborhood. As she took photos of the people and places in her community, she thought about how her Lower West Side neighborhood of Chicago has weathered change, not only through pandemic lockdowns, but also the effects of violence and gentrification over the decades.

News that puts power under the spotlight and communities at the center.

Sign up for our free newsletter and get updates twice a week.

Now Solís, a queer, Mexican-born visual artist, photographer and educator is releasing a book reflecting on the resilience and complexity of Pilsen through images made of people and places during the pandemic. The limited-edition book, Luz: Seeing the Space Between Us, is slated to be published in early September in both English and Spanish. She is currently trying to raise $3,000 to cover additional publishing costs due to supply issues.

“It’s sort of a love letter to the community and a love letter to the practice of photography,” said Solís, who worked as a documentary photographer from the 1970s through the early 1990s for neighborhood newspapers, Spanish-language publications and as a freelancer for the Chicago Tribune.

It’s a return to photography for Solis, 66, who has spent the last two decades focused on illustration and painting as well as her continuing work as an educator. She has organized and taught several illustration and photography, including workshops for mothers and daughters through Mujeres Latinas en Acción. Currently, she is working on a project on kinship and chosen family in the LGBTQ+ and Latinx communities.

Borderless spoke with Solís about her connection to Pilsen and her return to photography after over 20 years.

In high school, I was anti-war. We wore black armbands to protest the Vietnam War, and we were really involved. The Latino students, not all, but a lot of us, were more radical. We had alliances with the Black students too. So when I went to University of Illinois Chicago in ‘73, right away I joined political groups. It was part of my formation, my being interested in issues of social justice. I was always interested in doing work through my photography and my artwork that benefited the community somehow.

There was a lot of intersectionality. We had immigration issues, we still do, we had housing issues, we still do, we had fighting gentrification, Plan 21, we still do, environmental pollution, we still do. Right back here, you can see the tower from the old power plant. I’ve been battling cancer on and off for over 30 years and am currently battling lymphoma. A lot of people in the neighborhood have asthma or cancer. There was a lot of grassroots organizing, and I grew up in that atmosphere.

Fast forward to pre-pandemic and pandemic, right around 2019 and 2020. I started to walk a lot, even though we were told “don’t go outside.” I was walking like, six in the morning or seven, so I didn’t really run into too many people. If I did, we would cross the street because it was so scary to be out. I took my cell phone, and started taking photographs with it. In those walks, I saw the neighborhood like I had never really seen it, because I really slowed down. Once I started going out and photographing, I couldn’t stop.

I first started photographing buildings and places and noticing less and less panaderias (Mexican bakeries) and grocery stores – everything was closing, closed or being bought out. I wanted to showcase people from different generations. I really wanted to get people who lived here for a long time, or had some sort of tie to Pilsen. Some of them didn’t live here anymore. Others never lived here, but came here for different things such as cultural arts, not just food. Everyone in the book has a tie to Pilsen in some way or another.

During the first spring in the pandemic, people were starting to go out and do things, but they were cautious. We all were. I was fascinated by the closeness that I had to get, even though we were running through a pandemic. A lot of times people talk about the photographer’s gaze – I was interested in their gaze upon me, and that communication we have. It’s like, talking a little bit, getting to know them. Both of us are feeling each other out. They’re like, “What would you like me to do?” And I ask people to, “Think about how you would like to be seen, not how I would like to see you or how someone else would.”

For me, photography is about knowing that when you do this kind of work, it’s impossible for you to feel like you’re doing it all on your own, because without the people you’re working with or collaborating with, you wouldn’t be able to do what you’re doing. My work has always been done in communion with others. I prefer to work with them as collaborators as opposed to my subjects. I feel that they feel they get a lot more out of it. I want them to feel that they have control over the type of work that I’m doing with them, as opposed to me posing them a certain way.

The whole idea of seeing “the space between us” is seeing literally the communication between two people. Or you could also say, seeing the landscape, seeing the building, but it’s mostly about people. There’s a lot of silent communication, if you want to call it that, between myself and the person I’m photographing. Once we become really comfortable, it becomes so much fun and we don’t have to talk.

I arrived here [to Chicago] when I was eight months old. My dad was here. He went ahead. He worked for Rock Island Railroad. And then he sent for my mom and I from Mexico. We moved to Pilsen in the early ‘60s. I moved here to this apartment in 2006. I have wanted to live on this block since I was a child.

For me, being a resident of Pilsen means embracing the community, the good and the bad. You have to say it that way. You know this neighborhood was very different from when I grew up. I think it was a really rough place to live. When I was a kid, there was a bar on every corner. I’m not lying, there was a lot of violence. There’s still violence all around us.

But we still found the time to be kids. We played at Dvorak Park, we learned how to swim, we went to the field house, there were camping trips, there was all kinds of stuff. When you are a kid, you try to have a good time. We saw some harsh things as well. There were a lot of shootings, there was a lot of gang activity, a lot of problems with the housing.

I think what I love most about Pilsen is it has a lot of this history of people being very resilient and also fighting for justice. It’s been going on even before this neighborhood became primarily Mexican, with the other groups that lived here before, the immigrant groups.

The Czech Bohemians, and even the Irish that were actually first. All these people were fighting for better living conditions. Eastern Europeans, they had a lot of people who were involved in socialist organizations. So Pilsen is a unique neighborhood. And even though it’s been super gentrified now, it’s still a really strong community.

Read More of Our Coverage

I live right next to the Senior Center. I thought I might end up there, because I’m getting up there in age and I need to find a place to live. I won’t be able to go up the stairs, probably in eight more years – my knees already hurt, you know? So, I don’t know if I’ll be living here.This was a pretty low rent apartment, but not anymore. So how much longer could I, on the money I make, be able to afford to live in this community?

That’s what saddens me, that I may be one of those people having to move out, but it changes, right? And gentrification is everywhere. So what I like about Pilsen is the history, the people that I grew up with, I feel like it’s really home. I’ve lived in other countries and I’ve lived in other places, and I’ve loved them but I’ve always come back here.

Gentrification has altered the visual landscape of the community tremendously. I think one of the things that struck me the most was the disappearance of the Mexican bakeries. It really shocked me to see that there’s almost none left. I was never one for pan dulce even when I was growing up, but I just loved the smell of it and going in there buying it for my family or other people.

I want people to see their neighbors in my book. I want them to see themselves a little bit in this book. I want them to know these people and their stories. I want people to know that we want to present ourselves with dignity.

I’m just happy to be alive because I’ve had a lot of brushes with cancer. I’m happy to be doing the work I’m doing. For the first time in my life, I’m doing what I really love to do and doing it almost full time. That almost never happens!

Diana Solís still needs $3,000 to get the book printed, because of rising costs due to supply issues. You can donate to help Solís publish her book via Zelle at [email protected], Venmo @Diana-Solis-47 or contact her at [email protected] to send a check donation. Her 3Arts page outlines what your donation will get you.

Editor’s Note 8/1/22: A line within this article has been removed at the interviewee’s request.