Amanda Cervantes and Jose Luis Benavides look at how far the queer Latinx community has come in their work with Chicago’s Gerber/Hart archives.

In 2016, Jose Luis Benavides was working on an experimental documentary, Lulu en el Jardin, about his mother’s experience as a queer Latina in the ’70s and ’80s. At the time, the Chicago video artist and documentary filmmaker was getting his Master of Fine Arts degree at the University of Illinois at Chicago and was creating work about his own personal archives and queer family histories. He asked Amanda Cervantes, a photographer who was also a student at the time, to play the part of his mother for reenactment scenes. It was the start of an incredible friendship and collaborative relationship.

Benavides and Cervantes, who are both queer Latinx artists, have since created works that respond to archival collections both personal and public. The two are now working on a project they are tentatively calling “Amigas Latinas Queer Time” that reflects their explorations of the archive of Amigas Latinas. Between July 1995 and July 2015, Amigas Latinas built community in Chicago for lesbian, bisexual, transgender and questioning Latinas, beginning as a monthly discussion group and evolving into a primarily volunteer-run nonprofit. Its archive is housed at the Gerber/Hart Library and Archives.

News that puts power under the spotlight and communities at the center.

Sign up for our free newsletter and get updates twice a week.

In the fall, Benavides and Cervantes will launch a website that presents artworks, conversations and writings inspired by this trove of archival material. The project is an extension of “Inner Lives Out: Archiving Queer Time/Vidas interiores hacia fuera: Archivando tiempos queer,” a bilingual online exhibition they launched in 2021 that explores queer time and queer kinship across generations and identities.

Borderless Magazine interviewed Cervantes and Benavides about their latest exhibition and how the Amigas Latinas collection is a continuation of their work that delves into archival collections and “queer time.”

Borderless Magazine: What is queer time?

Jose Luis Benavides: In 2005 queer theorist Jack Halberstam wrote, “Queer Time and Place,” where he argues “queer uses of time and space develop … in opposition to the institutions of family, heterosexuality, and reproduction.” Basically, there is a timeline that is part of heteronormative culture that moves linearly with particular milestones. For example: You’re born. You go to school. Get married. Have kids. Have a career. Have grandkids, retire, and die.

But if we’re thinking about queer life paths, cycles and timelines, you may come out in high school or college, but also you could be someone that comes out at 50 or 60! If that is when you start having the sex and romance you want for the first time in your life, it gets even more complex. Because when queer people are putting themselves in different categories of time by “delaying” adulthood because of experiencing an “adolecence” later in life, it’s not good or bad. It’s just a different timeline. And for some people going back in the closet, like my mom did, you may experience time linearly but then you go backwards.

Jose Luis Benavides, “Lulu’s Journal,” 2017, digital video, 04:32 min

Borderless Magazine: You made a video about your mother called “Lulu’s Journal.” What is it about?

Benavides: I made an experimental documentary film about my mother’s life called Lulu en el Jardin. Her story is one of these queer timelines, literally. She was institutionalized in Chicago in the ’70s the first time she came out, emancipated herself at 18 and then lived on the streets. After she had a son (me), she ended up going back into the closet for what at the time was survival. “Lulu’s Journal” is an excerpt from the film. Back then my mom didn’t have access to something like Amigas Latinas, and if she had, I wonder if she wouldn’t have gone back in the closet. This Amigas investigation is about getting access to that space and time, and imagining a life where she could have had the support to not go back into the closet.

Borderless Magazine: Your current collaboration is a response to the Amigas Latinas archive. How did you find the archive, and what does your response look like?

Benavides: I came across the Amigas Latinas archive through a public Zoom talk done by Gerber/Hart during the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic. Our collaboration has been an investigation of Amanda’s and my relationship to this archive and a personal, deep dive into our own archives. We look at the way we relate to queerness, our own family histories, personal histories and then connect that to the Amigas Latinas archive. We were working through queer histories and queer interpretations of elder figures in our lives — for me, my mother, and Amanda, her great-grandmother and her aunt. I think now we’re doing the same thing, but this time they can talk to us. The queer elders who were part of Amigas Latinas are alive. They’re not ghosts.

Read More of Our Coverage

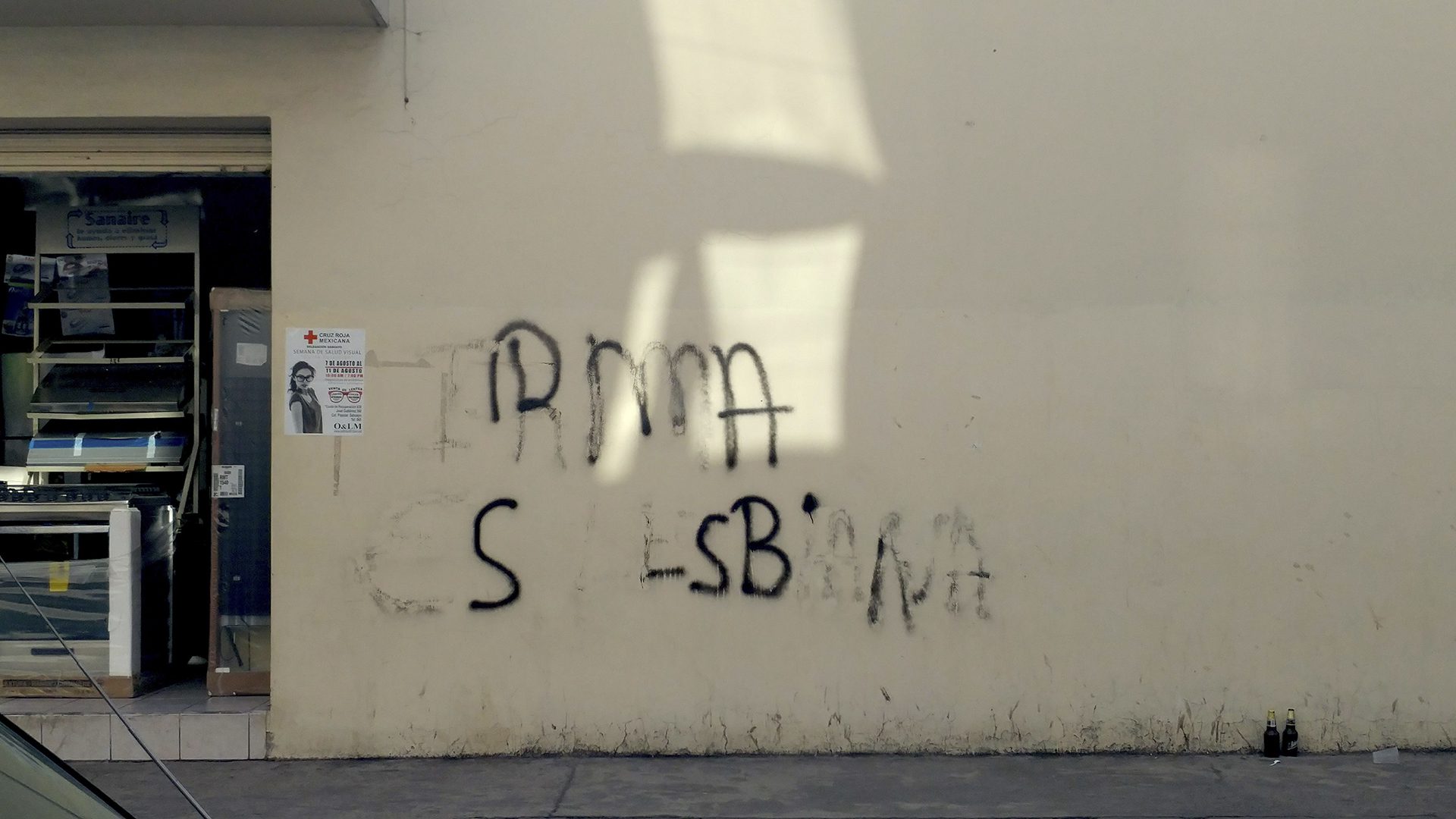

Amanda Cervantes: It is us making artistic responses to the archive. There’s a few things that we are working on. The first thing is recreating the flyers and photographing them being handled. These folks were sending hundreds of these flyers in the mail every week. We’re thinking about the ways that we want to honor the work and labor that went into producing these and sending them out, and thinking about how this was a physical social network that existed.

Benavides: We want to recreate the world of the flier — the whole atmosphere of how they were made, to how they ended up on someone’s fridge or in someone’s back pocket. That’s also part of one of the reenactment videos I want to make: a scene that is featuring the flyers in its original environment.

The video is a continuation of my mother’s story. I have recordings of my mother talking about her experiences in the ’80s and the ’90s. The idea for me is that I’ll be able to turn those recordings into a story that runs parallel with the Amigas Latinas records.

I found in the Amigas Latinas fliers that so many of their platicas (chats) were addressing topics that directly apply to someone like my mom at the time: being closeted, having families, coming out, being working class. In this video I’m working on, I’m imagining her in that space with Amigas. Imagining how she could have navigated coming out and having the support that Amigas Latinas existed to provide, wondering what it would’ve been like if Amigas had been part of her life.

Jose Luis Benavides, “Amigas Latina’s flyers,” 2021, GIF. Images courtesy Amigas Latinas papers at Gerber/Hart Library and Archives

Borderless Magazine: What are the critical questions you asked yourselves during this process? Did you encounter any challenges?

Benavides: Some critical questions we’ve asked ourselves through this process have been around nostalgia, how we relate to these pasts — both our own personal histories, family histories — and how we relate personally to these archives, while being careful about ethical approaches in sharing these lesbian Latina women’s images and work from the 1990s. We are not trying to glorify them. They admit they had issues around trans inclusion and racism. People had to struggle to have more representation within the group. That’s a growth process.

In terms of the care we took and the ethics, we had to redact personal info from the fliers, which are also personal invitations. There were names, numbers, and addresses of people who were not out and we want to be respectful and not put people in danger or compromised situations.

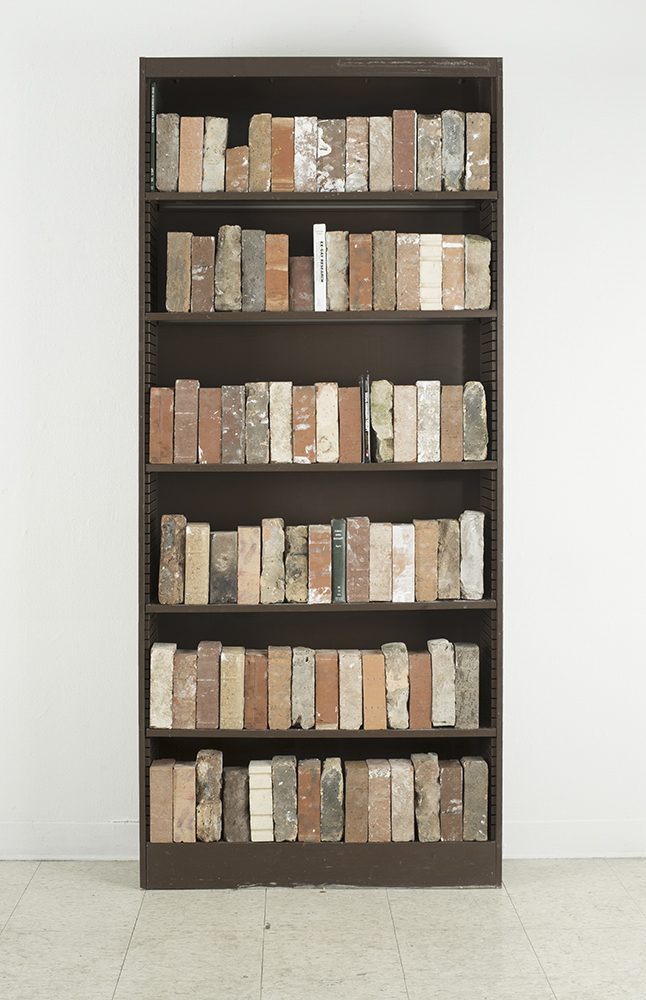

Borderless Magazine: Are there other particular objects or documents in the archive that you are interested in beside the fliers?

Benavides: We’re very interested in other ephemera in the archive, including educational pamphlets and business meeting notes, among other photographs and newsletters, and Amigas Latinas’ softball uniforms. Funnily enough the uniforms are another overlap with my mother’s story. She tried to join the softball team at Truman College but didn’t succeed or didn’t stick with it. I forget, but I feel that mirrors the way [Amigas Latinas cofounders] Evette and Mona described their own team as a bit of a failure, too, because they told us how the team was terrible but it never mattered. They didn’t play to win, they played because it was something to do together.

Borderless Magazine: What are you hoping people experience when checking out your online exhibition?

Benavides: Gaps in history are just kind of inevitable. Archives can be places that produce those gaps, or archives can be a place that closes those gaps. We want to expose and talk about things we hadn’t talked about or seen before, and finding the Amigas Latinas archive, we now have an abundance of imagery and things to work with. We’re just super geeked out and excited.

Cervantes: Learning about this archive and doing this work is a way of showing my past self, my current self, and also other queer youth, that we’ve always been doing this work.

Just 20 years ago, it was a different world for people like us. It was before social media, before everybody had access to the internet. It was this time where they came together and put in the work to talk about these topics that these women really wanted to hear, heavy-hitting topics at that. Whereas now, you can look up anything and everything in the palm of your hand. I think it’s a reminder of how far we’ve come and how we can honor our past as we move forward in the future.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

This story is in collaboration with a podcast series by the Gerber/Hart Library and Archives titled Unboxing Queer History. Check out episode 3, Amigas Latinas – Latina, queer, and together: