Max Herman/Borderless Magazine

Max Herman/Borderless MagazineA year after the city’s largest migrant shelter turned into a temporary intake zone for unhoused individuals, the Shelter Placement and Resource Center sometimes takes months before placing them in homeless centers, some residents say.

Ashley Bello has faced several dead ends in her hope to find safe and stable housing.

She has left shelters for safety concerns and aged out of facilities after turning 25.

For two days, she slept on the ‘L’ train before temporarily staying at a friend’s home. After returning to the streets, she visited a drop-in center for families and individuals experiencing homelessness.

News that puts power under the spotlight and communities at the center.

Sign up for our free newsletter and get updates twice a week.

That’s when she was referred to the Shelter Placement and Resource Center (SPARC). The city-run intake center felt like a fresh opportunity and much-needed help in finding a safe and stable place to live, Bello said.

But after arriving at the city-run intake facility in August, her struggle to find a home continued.

She remembers being told she would be placed in a designated shelter within two weeks after arriving at the intake center. But two months went by as she waited — sleeping on thin mats with bedbugs and witnessing fights frequently breaking out inside.

“It was very stressful,” said Bello. “I couldn’t sleep. It was just draining.”

SPARC is meant to serve as an intake center — a brief stopover point for unhoused Chicagoans to access resources while waiting for placement in a city shelter. The center was intended to be a new chapter in the city’s efforts to expand services for unhoused people, repurposing a former migrant shelter in Pilsen that had poor and inhumane living conditions. A Borderless investigation, however, found the former shelter-turned-intake center is falling short in its promise to connect unhoused people with dignified, long-term shelters.

Over a dozen current and former SPARC residents Borderless spoke to said they have waited up to six months at the center, enduring poor conditions such as bed bugs, rats and frequent fights while waiting to be placed in a shelter.

Months later, Bello finds herself back at SPARC, having left the shelter she was placed in after two and a half months, wondering how long it will take to find a place to live.

A former migrant shelter

Before it became SPARC, the city operated a migrant shelter in the building at 2241 S. Halsted St. on the city’s Lower West Side. The Halsted shelter — a converted warehouse in one of the city’s industrial corridors — was part of a network of buildings used to house some of the 30,000 migrants bused to Chicago between 2022 and 2024 as part of Texas Gov. Greg Abbott’s Operation Lone Star. At its peak, more than 2,300 people stayed at the Halsted shelter.

A December 2023 investigation by Borderless found inhumane conditions at the shelter, with residents describing freezing temperatures, unsanitary bathrooms, and cramped living quarters. Just days after the investigation was published, five-year-old Jean Carlos Martinez Rivero died from sepsis after getting sick at the Halsted shelter.

Read More of Our Coverage

In the spring of 2024, the Chicago Department of Public Health confirmed tuberculosis cases among newly arrived migrants staying at the shelter, as well as cases of measles, the first in the city since 2019.

Ultimately, city officials closed the migrant shelter in October 2024, ending a city contract with its former shelter operator.

Hector, a Nicaraguan immigrant, sought shelter at the Halsted location last year after living with his partner on the streets in the snow for two weeks. Hector is only using his first name because of fear of retribution.

Around the time of his arrival, the warehouse was repurposed from a migrant shelter to an intake center as part of the city’s efforts to merge the migrant and existing homeless shelter systems.

Read More of Our Coverage

“We are shifting to a more cost-effective, equitable, and strategic approach that addresses homelessness for all who need support in the City of Chicago,” Mayor Brandon Johnson said in an announcement of the One System Initiative last year.

Hector said that while he stayed there for at least a month, there wasn’t enough food and that the sleeping area was crowded.

“I’ve experienced a lot of things living on the streets, but I am not used to being with that many people,” he told Borderless in Spanish.

Instead of taking his chances with shelter placement, Hector and his partner decided to live out of an abandoned truck they found. He frequently goes back to SPARC, however, because he has friends still staying at the building.

“We cleaned the truck, and thanks to God, we are there now.”

‘Not intended for long-term placement’

In December 2024, the city began using the Halsted building as its first physical intake center, called SPARC, for single adults without children, according to a 2025 annual homelessness report by the city.

The site is “intended to be a reliable, safe, and 24-hour site for up to 250 to 300 single adults to wait for coordinated transportation to a shelter when a bed is available, without having to sleep outside or in places not intended for human habitation,” according to a city scope of work document.

The Department of Family and Support Services (DFSS), the agency tasked with addressing homelessness, stated in a written response to Borderless that SPARC is intended to be a temporary location where individuals can wait for shelter placement, not a long-term residence.

However, the SPARC building is located in a planned manufacturing district intended to accommodate manufacturing, warehousing, wholesale and industrial uses — not for residential use.

“SPARC is not a shelter or housing location and is therefore not zoned as a shelter or housing site,” a representative of the Department of Family and Support Services (DFSS), the city agency tasked with addressing homelessness, told Borderless in a statement.

As of Sept. 2, 2025, the average length of stay for individuals at SPARC was 8.5 days, according to DFSS.

However, over a dozen current and former SPARC residents told Borderless that they had stayed at SPARC for much longer, with some residents staying up to six months at the intake center.

“It’s just a waiting game,” said Bello, who ultimately stayed at SPARC for two months after being told she would be placed in a shelter within two weeks.

Sadiq Adeniran, a Nigerian immigrant who is between jobs, checked into SPARC and expected to stay there for only one to two nights. Two months later, he was still there.

Stephen Batom, another current SPARC resident, said he’s been waiting for placement at SPARC for six months now. He told Borderless he hopes to find a home soon, somewhere on the West Side, where he grew up.

Ethan Davenport, a former SPARC resident, said that he stayed at SPARC for over two months in the spring. Since leaving, he joined the Illinois Union of the Homeless, a volunteer-based support and advocacy group for the unhoused. He frequently goes back to SPARC to distribute food and donations to current SPARC residents.

“There are still residents there from before I was there,” said Davenport. “The least I’ve heard [someone staying there] is a month.”

In response to Borderless’ findings, DFSS stated that shelter bed availability for single adults is limited, resulting in longer wait times for shelter placement.

“However, individuals are able to remain at SPARC for as long as it takes to be connected to a shelter bed through the centralized shelter placement process,” the department said in a written statement. “DFSS looks for opportunity to increase capacity with the shelter system through expanding services with existing providers and through new opportunities.”

DFSS partners with Franciscan Outreach and The Salvation Army to operate SPARC. Franciscan Outreach, a nonprofit organization based in Chicago, manages day-to-day operations while The Salvation Army connects unhoused individuals with long-term shelter placement.

Brian Duewel, senior director of communications at The Salvation Army North and Central Illinois Division, said there are designated pick-up times to help streamline placement operations, but “there were circumstances that occasionally resulted in longer wait times for placement.”

These factors included the individual’s absence or lack of readiness to proceed with placement at the scheduled time, as well as a shortage of beds for certain populations, according to Duewel’s written statement.

“With no possible match to a shelter, wait times increase,” said Duewel. “Despite these nuances, the established process was designed to be responsive and flexible, ensuring individuals were transported as soon as beds became available while balancing safety, urgency, and system-wide demands.”

Luwana Johnson, senior director of programs and operations at Franciscan Outreach, said that while the intended length of stay at SPARC is short-term, some guests may remain longer “due to factors largely outside of Franciscan Outreach’s control.”

“These include limited shelter bed availability citywide, guests being unavailable at the time of placement, refusal of offered placements, or restrictions related to specific shelters,” said Luwana Johnson. “These challenges contribute to variations in length of stay for some individuals.”

While the normal capacity is 200 individuals, the capacity was expanded by an additional 200 to serve more individuals during the winter weather months, according to DFSS. Of the 400 available beds at SPARC, about 340 are occupied as of early December, said the department.

In January, the nonprofit organization A Safe Haven will assume the role of intake operator, replacing The Salvation Army, which had a contract with the city to handle the centralized shelter placement process for four years. According to the city’s scope of work document, A Safe Haven will be responsible for completing shelter placement within 24 hours of an individual’s request for shelter.

‘Just like a prison’

While the Salvation Army handles intake coordination for shelters, DFSS has a $4.5 million contract with Franciscan Outreach to manage operations at SPARC through December 2026. Franciscan Outreach’s mission is to “provide healthy meals, safe shelter and critical services that affirm the dignity of men and women who are marginalized and homeless,” according to their website.

DFSS told Borderless that it is working with Franciscan Outreach to identify any maintenance needs or issues that require attention at SPARC. All identified issues must be reported to DFSS, officials said.

Over a dozen current and former SPARC residents Borderless spoke to identified serious health and safety issues with SPARC. These include rats in the building, bed bugs on the mats and sheets where people sleep, and poor security.

Tanisha Pepper said she stayed at SPARC for a little over a month in June following her divorce. It was the first time she stayed at a homeless shelter, and she said she was upset at the conditions and how unsafe she felt.

During her time at SPARC, Pepper said she didn’t have access to washers, dryers or towels. She also said she saw fights breaking out often and that the security staff didn’t intervene.

“They run that facility just like a prison,” said Pepper. “It is very unsafe.”

DFSS told Borderless that Franciscan Outreach hosts bi-weekly meetings to encourage residents to share their feedback. Residents can also report their concerns by filling out a grievance form or calling 311.

Pepper attempted to submit a grievance report about the shelter’s conditions using the grievance box at SPARC, but she said that the box was overflowing with reports and did not hear back about the complaints she reported. DFSS said grievance forms are reviewed weekly by the site director.

Dephentril Cunningham and his partner, Rose Murray, stayed at SPARC for about a month this summer. The couple said they slept on uncomfortable cots, rarely had towels to dry themselves after showering, and saw rats inside the shelter during their stay.

Murray, who was pregnant at the time, added that she was bitten by bed bugs on several occasions. She bought disinfectant spray to try to kill the bugs around her sleeping area, she said.

“Their reasoning [for the conditions] is they’re a placement shelter,” said Cunningham. “That’s their excuse for everything that they’re doing wrong, but [there have] been people there upwards of six months to a year. How that happens at a place of shelter, I don’t know.”

Luwana Johnson, of Franciscan Outreach, said the organization takes concerns seriously and that protocols are in place to respond to issues such as bedbugs.

“Given the transient nature of the population served, issues such as bed bugs and other infestations can occur,” Luwana Johnson said. “However, established protocols are followed to mitigate and reduce their spread, including routine extermination services for bed bugs, rodents, and other pests.”

The SPARC operator serves more than 700 unhoused individuals each month, many of whom present significant mental health issues, and staff members receive training in professionalism, trauma-informed care, harm reduction and customer service, Luwana Johnson said.

“The organization remains committed to responding to guests with care and dignity while maintaining a safe and supportive environment,” said Luwana Johnson. “SPARC functions as a supportive stabilization site in a city facing a significant shortage of shelter beds and affordable housing.”

Despite complaints about the conditions at SPARC, some former residents have had to return after their shelter placement didn’t work out.

Two months after SPARC placed Bello at the Young Women’s Leadership Academy shelter in South Commons, Bello finds herself back at SPARC.

She hoped she wouldn’t have to return there because the conditions were worse compared to those of other shelters she had stayed.

Before returning to SPARC, she said she called five different shelters asking for placement. Two said they were full and the other three said she had to be placed at a shelter by the city.

Without another option, she finds herself back at SPARC.

Advocating for more resources

In November, Ald. Byron Sigcho-Lopez (25th) told Borderless that the conditions at the building, particularly the overcrowding, have improved since it was used as a migrant shelter.

“This is night and day compared to what it was before,” said Sigcho-Lopez.

He said, however, that he has heard from unhoused people at SPARC that their biggest concern is the length of time they have to stay at the intake center. The alderman is advocating for more resources to address homelessness in the 2026 budget.

“The biggest obstacle is not having enough affordable or public housing options,” Sigcho-Lopez said.

Illinois has only 34 affordable rental homes available for every 100 extremely low-income renter households, according to a 2025 report from the National Low Income Housing Coalition.

The lingering impacts from the COVID-19 pandemic, combined with a struggling economy and housing shortage, has made it challenging for Chicagoans to get housed. According to city homelessness data, there are more newly unhoused people than housing resources can support.

During this crisis, members of the Illinois Union of the Homeless are advocating for improved shelter conditions and services for the local homeless community. Each week, they take a group of SPARC residents to a nearby laundromat and supply them with detergent and a few dollars to do their laundry. They also distribute food, clothing and other donations as part of their People’s Clinic.

On a recent Wednesday, union members gathered at an office near SPARC to participate in a virtual call with national union organizers and representatives from chapters across the country.

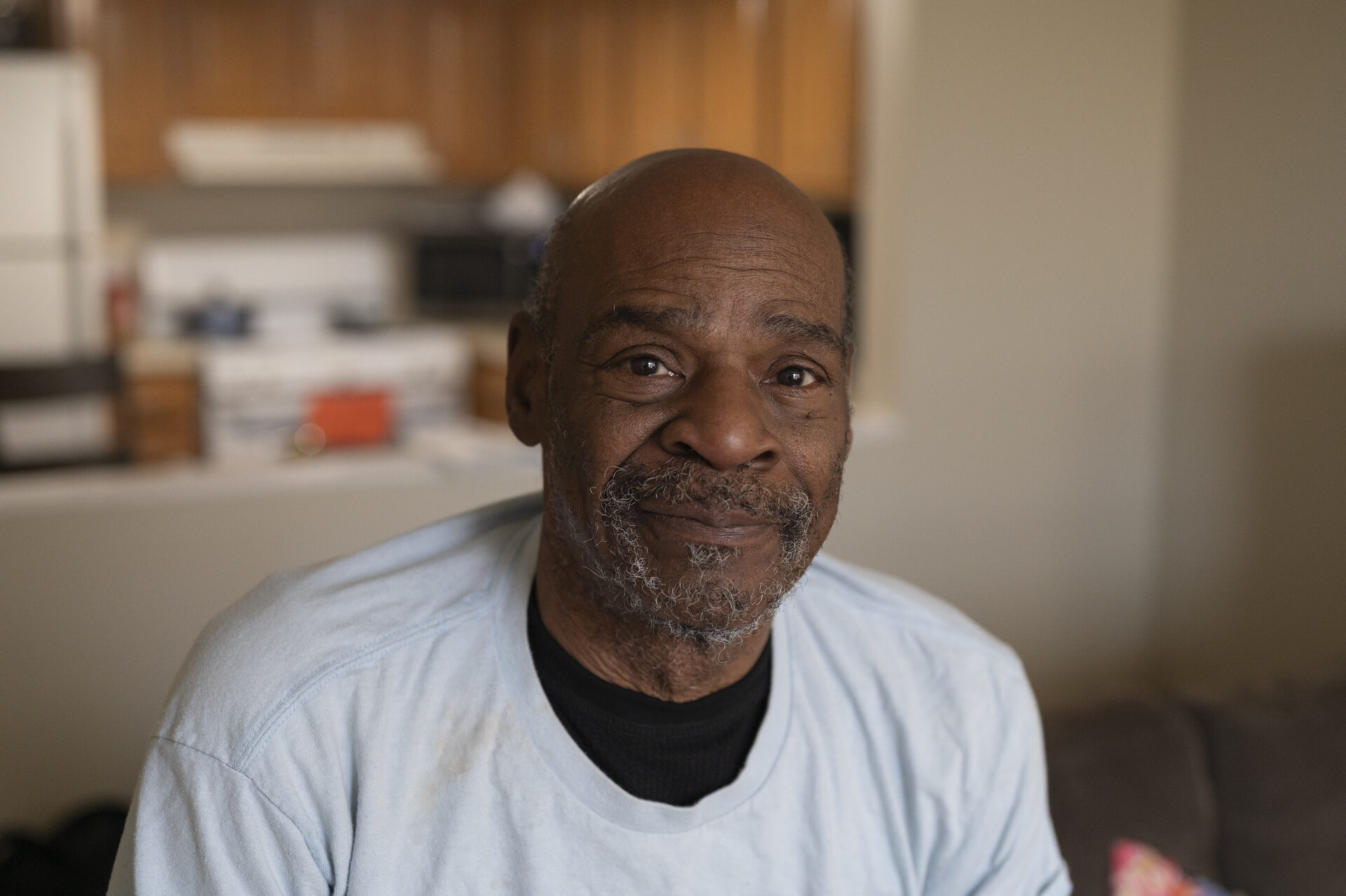

Gerald Bright, a former resident of SPARC, was there with eight other members of the Illinois chapter. He listened to the national organizer recite statistics about the growing housing crisis and the right to adequate housing that is part of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights. It was then his turn to share his testimony with the attendants.

“The conditions that I experienced at SPARC were atrocious,” he told attendees.

Bright, a 66-year-old retired security guard from Ohio, told Borderless that security guards at SPARC were unprofessional. Since there was no access to washers and dryers at the intake center, he had to wash his clothes in the bathroom. He stayed in SPARC for three months during the summer, during which he said he was required to carry his belongings up and down the stairs for meals with no assistance from staff.

“You have to carry this suitcase out with you everywhere you go, up and down steps; it’s really hard on the elderly,” Bright told Borderless.

Bright said he was placed in an assisted living apartment that costs $6,000 per month, which he pays for with health insurance and Social Security.

Despite the high cost, he doesn’t want to return to SPARC. He says he’ll keep fighting.

“They don’t know that we got God on our side,” Bright said, wiping tears from his face. “We got the power.”

Support for this investigation came from the Fund For Investigative Journalism.