Oscar Gomez/Borderless Magazine

Oscar Gomez/Borderless MagazineDescendants of Japanese Americans incarcerated during WWII gathered to remember the injustices of detention camps while calling for solidarity with other immigrant communities impacted by Trump’s sweeping immigration policies.

In 1984, Nancy Matsumoto’s grandparents built a small garden in their home near the edge of Lake Michigan. There, Tomiko and Ryokuyō Matsumoto planted shiso and myoga seeds, strawberry plants, and morning glories gifted to them by their Issei friends, fellow first-generation immigrants born in Japan.

The seeds, Nancy Matsumoto said, symbolized her grandparents’ resilience despite the struggles they faced resettling in Chicago after all they endured when the U.S. government incarcerated Japanese Americans during World War II.

“In one corner of our small garden I plow- / the flowers I intend to grow are large in number,” Tomiko Matsumoto wrote in a Japanese tanka poem. “The buds of myoga that we received from a friend in Oregon grow rampant and lush in the soil of Chicago.”

News that puts power under the spotlight and communities at the center.

Sign up for our free newsletter and get updates twice a week.

Matsumoto’s grandparents were among more than 20,000 Japanese Americans who resettled in Chicago after being released from incarceration camps in the 1940s.

80 years after the end of World War II, Japanese American community members in Chicago gathered at the Chicago History Museum for the annual Day of Remembrance. They reflected on the intergenerational impact of incarceration and how the community can continue healing and moving forward.

The event’s organizers also drew connections between their history and the current treatment of immigrant communities under the Trump administration. Since returning to the White House, President Donald Trump has prioritized attacking immigrants without legal status and threatening large-scale immigration raids and detention. These policies, organizers said, are reminiscent of the policies that detained and excluded Japanese Americans during World War II.

“We’re especially honored to be here today when the civil liberties of so many in the immigrant, BIPOC and LGBT communities are under assault,” Matsumoto said. “Remembering our own families, stories of unjust marginalization and incarceration will, I hope, serve as a call to action to dissent and to advocate for those whose civil rights are being threatened in our country today.”

The Executive Order to Incarcerate Japanese Americans

The Day of Remembrance refers to the day Franklin D. Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066 on Feb. 19, 1942. The executive order led to the forced relocation and detention of 125,000 Japanese Americans living on the West Coast during World War II. More than half of those incarcerated were U.S. citizens.

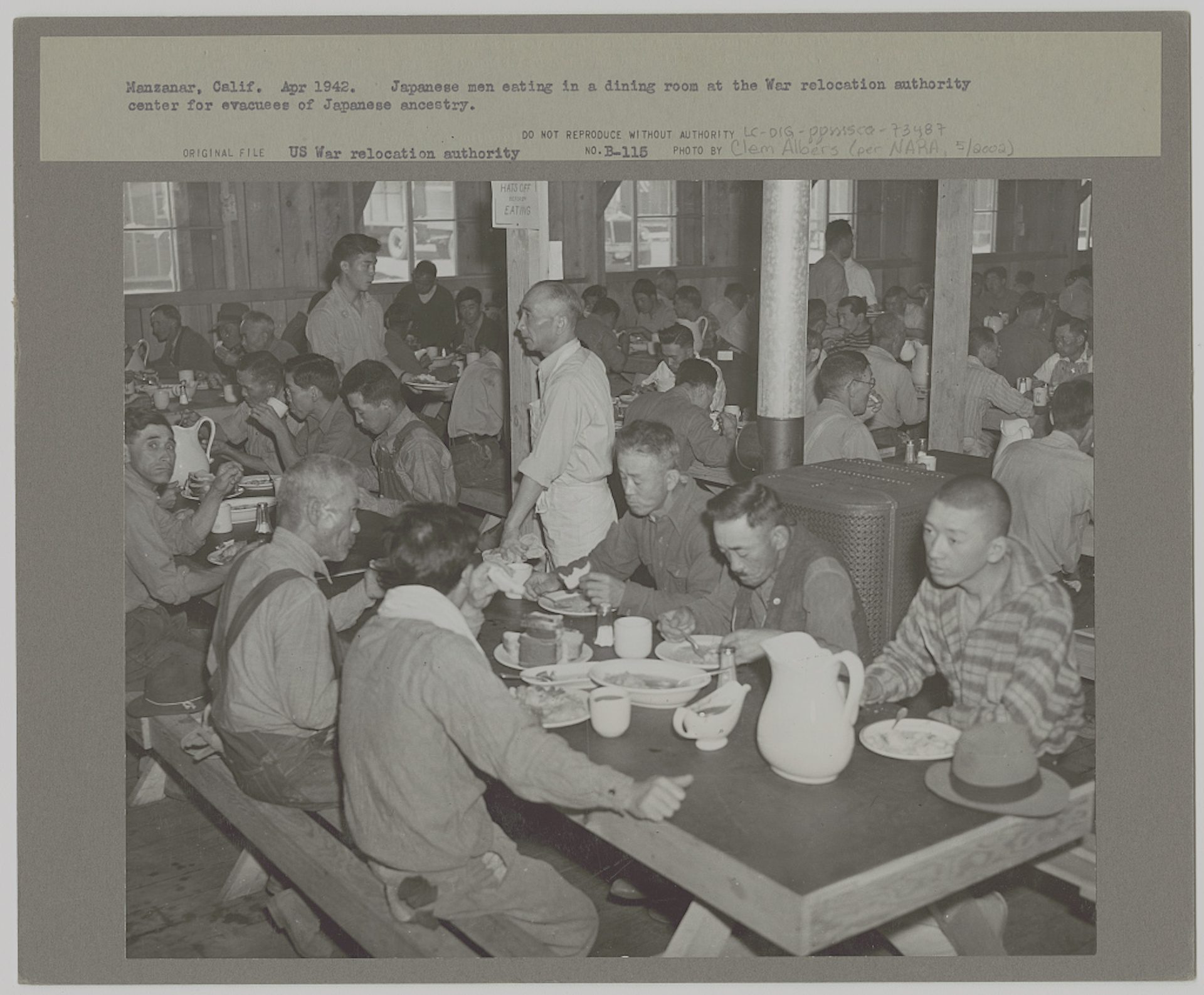

The U.S. government, through its military forces, detained Japanese Americans at camps in isolated parts of California, Arizona, Arkansas, Idaho and other states further away from the coast. While incarcerated, Japanese Americans slept in barracks and small rooms with no running water, according to the Library of Congress.

Harold Ickes, the U.S. Secretary of the Interior at the time, described the camps as “hastily constructed and thoroughly inadequate.”

“We gave the fancy name of ‘relocation centers’ to these dust bowls, but they were concentration camps nonetheless,” Ickes told the Washington Evening Star in 1946.

Almost 50 years later, Congress passed the Civil Liberties Act of 1988, which acknowledged the injustice of Japanese American incarceration and offered a formal apology and payments of $20,000 in cash to survivors of detention.

Read More of Our Coverage

The reparations came after a congressional committee determined the forced removal of Japanese Americans was driven not by military safety but by “race prejudice, war hysteria and a failure of political leadership.”

“There’s many people…that may not know about this history and may not understand what the Japanese American community had to go through and how they got established in Chicago,” said Bob Hashimoto, president of the Chicago Japanese American Council (CJAC).

Remembering Racist Atrocities

For decades, people in Chicago and nationwide have commemorated the Day of Remembrance for Japanese Americans incarcerated by the United States.

This year’s “Resilience in One Chicago Family” event was spearheaded by Japanese American Service Committee (JASC). Chicago Japanese American Council (CJAC), Japanese American Citizens League – Chicago Chapter (JACL), Chicago Japanese American Historical Society and the Japanese Mutual Aid Society of Chicago were also among several organizations co-hosting the event.

“Resilience in One Chicago Family” centered around Matsumoto’s grandparents’ poetry, which explored their forced relocation from Los Angeles to a detention center at Heart Mountain, Wyoming, and their eventual resettlement in Chicago after World War II.

The Day of Remembrance speakers highlighted lessons from Matsumoto’s grandparents’ poetry, looking at themes of hope and resilience in their writing.

“Labels are powerful and can be insidious,” said Eri F. Yasuhara, a Japanese literature scholar. “[‘Tekikokujin,’ or ‘enemy alien’] had an enormous effect on [Matsumoto’s grandparents’] lives because it was one of the justifications used for their incarceration.”

Japanese instructor and editor Mariko Aratani said the poetry form Matsumoto’s grandparents wrote in, tanka, allows for deep personal expression and holds an important place in Japanese culture.

Matsumoto’s grandparents’ tanka poetry, Aratani said, was an outlet for them to document their emotions amid the harsh desolation of incarceration camps.

“While being incarcerated in the camp, stripped of their freedom and facing uncertainty, they turned to tanka to express their emotions and preserve their cultural identity,” Aratani said. “In the barren environment…they found solace in 31 syllables that had shaped their lives.”

Jennifer Trautvetter, the event’s lead organizer and JASC’s program and special events manager, said the Day of Remembrance is a necessary time for people to learn more about Japanese American incarceration and the history of Japanese American communities here in Chicago.

While numbers are important to understanding the impact of Japanese American incarceration, Trautvetter said it is also important to remember the stories behind those numbers and the individual lives impacted by detention.

“When there is a more negative part of your country’s history, it’s important to learn that so you don’t repeat it in the future instead of hiding it and pretending like it didn’t happen,” Trautvetter said. “If we don’t learn about mistakes that were made in the past, it’s easier to repeat them.”

‘We Need To Be The Allies That We Wish We Had In 1942’

JACL Chicago Program Director Rebecca Joy Ozaki said there are parallels between what happened to Japanese Americans in 1942 and Trump’s efforts to dismantle birthright citizenship and utilize the Alien Enemies Act of 1798 to conduct mass deportations.

“We’re not the ones directly targeted right now, so with that privilege, how do we show up for other communities?” Ozaki said. “We need to be the allies that we wish we had in 1942.”

Ozaki coordinated an effort alongside other organizations involved with this year’s Day of Remembrance in Chicago and nationwide to publish a letter to the Japanese American community encouraging readers to take action against Trump’s immigration plans, particularly his efforts to use the Alien Enemies Act to target immigrants without legal status.

“Raids across the country are terrorizing immigrant communities reminiscent of the FBI raids that ripped Issei from their homes and inspired others to keep a toothbrush by the door in case they were next,” the organizations wrote in the letter. “…The repetition of history is upon us.”

The Alien Enemies Act allows a president to detain, relocate or deport noncitizens who are from countries considered ‘enemies’ of the U.S. during wartime. The act was the legal basis for Executive Order 9066 and the incarceration of Japanese Americans.

Since taking office, Trump has made immigration and deportation of people without legal status a top priority. His administration is working to ramp up Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) raids and arrests, detaining immigrants at Guantanamo Bay’s detention facility, building immigrant detention facilities on military bases, and contracting with a private prison company to detain immigrant families.

“No one should be facing what is happening now, regardless of time, or people, or who it is,” Ozaki said. “Especially from their government.”

In the 1940s, Ozaki’s grandfather and family were moved to a relocation center at Santa Anita Racetrack in California. In conversations with Ozaki, her grandfather said the U.S. government “treated the animals better than they treated him” while detained at the racetrack.

Ozaki’s grandfather, the first Asian American principal in Chicago Public Schools, according to the Chicago Tribune, passed away in 2015.

Lessons of Healing and Resilience

CJAC President Bob Hashimoto said for great-grandparents and grandparents who lived in or were direct descendants of those who were incarcerated, speaking about their experiences can be difficult.

Hashimoto, who is Sansei, or third-generation Japanese American, said that when he was younger, he was told not to learn Japanese and to distance himself from his culture to be more accepted.

But now, Hashimoto said, many younger generations of Japanese Americans are finding ways to learn more about their history and grandparents’ experiences.

“The fourth generation [Yonsei] is asking more about: ‘How come we don’t know more about our heritage?’” Hashimoto said. “They’re starting to gravitate back towards asking those questions and looking into their grandparents and how all this happened.”

For the organizers of the event, speaking about Japanese American history served as an important reminder of the need to advocate for other immigrants and marginalized communities whose civil rights are under attack today.

But central to the Day of Remembrance, too, was thinking about how the Matsumotos and thousands of other Japanese Americans built lives for themselves and future generations despite their challenges and hardships.

“In this current time of so many uncertainties, perhaps we can find strength in and learn from our forebearer’s resilience against all odds,” said Kyoko Miyabe, a Japanese American translator and artist and the final speaker at the Day of Remembrance event.

“[They endured] hardships through acts of creation, whether through poetry, agriculture or horticulture, never losing hope for future possibilities.”

Katrina Pham is Borderless Magazine’s audience engagement reporter. Email Katrina at [email protected].