Efrain Soriano for Borderless Magazine

Efrain Soriano for Borderless MagazineChicago is phasing out Favorite Healthcare Staffing after paying the agency $342 million to oversee its shelter system. Records show that Favorite had a poor track record of resolving complaints.

This story was a collaboration between the Investigative Project on Race and Equity and Borderless Magazine.

Reina Isabel Jerez Garcia filed a grievance with the City of Chicago last fall when staff started serving smaller meals at the city-funded migrant shelter where she and her teenage son were staying.

Dinner was a scoop of rice and a couple of pieces of meat at the Super 8, a compact motel building on the far North Side. The city’s main shelter contractor, Kansas City-based Favorite Healthcare Staffing, opened the shelter at the Super 8 in July 2023.

Other changes at the shelter worried Jerez, 40, a lawyer and advocate for the rights of victims of violence in Colombia. Amid increasing threats from guerilla groups, she and her family left the city of Cúcuta to seek asylum in early 2023.

News that puts power under the spotlight and communities at the center.

Sign up for our free newsletter and get updates twice a week.

She said shelter staff, who worked for Favorite, wouldn’t let anyone, even kids, take more than two bottles of water a day. Staff were also blocking residents from bringing in donations of winter clothing, though the temperature was dropping, and the shelter wasn’t providing any to arriving families.

“The treatment was terrible,” said Jerez. As she and her son, then 16, awaited the arrival of the rest of their family — Jerez’s husband, two younger sons and an adopted daughter — she organized with other residents to push back against the changes.

In grievances filed later that year, another migrant parent said that Favorite staff blamed the food shortage on the city. “I don’t believe that the government told them to only give us a spoonful of rice,” the resident wrote in Spanish in a December 2023 grievance, adding that workers treated residents with hostility. “Enough with the xenophobia.”

Parents at the Super 8 filed 12 grievances between August and December 2023, most alleging misconduct by the shelter manager, a Favorite contractor. They urged city officials to intervene. But Jerez said she and her neighbors never heard back about their complaints.

Over the last two years, the City of Chicago built an unprecedented shelter system to provide safe, temporary lodging and resettlement resources to incoming migrants like Jerez and her family.

But as complaints against shelter staff poured in, the city passed off much of the work of overseeing that system to Favorite contractors, according to a review of hundreds of pages of public records, including contracts, invoices and emails, obtained by the Investigative Project on Race and Equity and Borderless Magazine.

The analysis of grievances filed in the last half of 2023 revealed a poorly attended system. Contractors let complaints sit for weeks or months without response and rarely recommended discipline for staff members accused of misconduct.

Migrants’ allegations against staff ranged from cruel treatment and threats of eviction to more serious charges of discrimination based on migrants’ sexuality or nationality and the denial of emergency medical care or accommodations for medical or disability needs. In some cases, staff accused of misconduct — such as the shelter manager at the Super 8 — were assigned to investigate and respond and close out complaints filed against them, records show.

Read More of Our Coverage

The Investigative Project and Borderless found that these records also included several grievances likely filed by other contracted shelter staff, who alleged that their coworkers or supervisors were enforcing shelter rules unevenly, acting inappropriately with residents, or, in one case, serving meals that had been plated with rotten chicken.

Meanwhile, in dozens of interviews with the Investigative Project and Borderless, residents and staff expressed disappointment with city oversight. Several described the shelters as a “toxic” and “hostile” environment, where people got leadership positions out of favoritism rather than experience working in resettlement services or with asylum seekers. Some said that attempts to improve conditions or report misconduct were either ignored or led to retaliation.

“Their needs are met as far as shelter and food, but we really don’t help them,” said a former contractor, who requested anonymity because they were scared of losing future contract work opportunities. “We really don’t. We try our best, but like, there’s nothing we can do for them.”

At its peak in January, the city’s migrant shelters housed just under 15,000 residents, more than a third of them small children, according to city data. They slept on bunk beds in small motel rooms and cots in congregate spaces in fieldhouses, former schools and industrial buildings.

The city’s reliance on Favorite to staff these shelters has come at a high cost. Since September 2022, more than $3 of every $5 spent on migrant care — roughly $342 million — has gone to Favorite for staffing and oversight.

For months, the city defended its contract with Favorite.

“Favorite is our only solution,” Department of Family and Support Services (DFSS) First Deputy Commissioner Jonathan Ernst told the Chicago Tribune in August.

The following month, Chicago Mayor Brandon Johnson increased the city’s contract with the company by another $100 million.

However, shortly after, Johnson announced in late October a plan to shut down most of its migrant shelters by the end of the year while integrating 3,000 remaining beds into the city’s existing homeless shelter network. That network will accept migrants who have arrived in the United States within the last 30 days but will no longer guarantee them beds — and Favorite will be phased out as a shelter contractor, said DFSS Commissioner Brandie Knazze.

City officials have continuously praised the city’s work in caring for newly arrived migrant families over the past two years. “We fought back and showed the world just how welcoming we can be,” Johnson said at the October press conference announcing the end-of-year shelter closures.

Before the announcement, experts called to overhaul the system and its contract with Favorite.

“It’s time for the city to step back and evaluate the shelter system and try to figure out how to improve it,” said Nicole Hallett, director of the Immigrants’ Rights Clinic at the University of Chicago Law School. Before the announcement, she said, “there’s no reason why these contractors should just get renewed contracts over and over again without any review of the work they’ve already done.”

Records Denial

The city’s migrant shelter system has remained shut off from public scrutiny. Few organizations are allowed to provide services inside the shelters. Under the terms of its contract, Favorite must seek approval from the city before making public statements, and its contractors are barred from speaking to the press. City officials and Favorite spokespeople declined multiple interview requests about the grievance process but defended their efforts to improve their QR code-based grievance system since launching it in June 2023 in written responses.

“Favorite takes its role in the grievance process for its employees and new arrivals very seriously,” Favorite Senior Vice President Keenan Driver wrote in an emailed statement. “To that end, Favorite worked with the City to review and update the grievance processes at the shelters in late 2023 to ensure more rapid processing and a safe environment in the shelters for workers and residents.”

One of those late 2023 improvements was to hire two full-time Favorite contractors who would be “solely responsible” for resident grievances, according to Julie Gilling, director of advocacy and policy at DFSS. Previously, responsibility was split between “a few team members overseeing operations at new arrivals shelters,” Gilling wrote in an email response.

More recently, the average response time for grievances decreased to 13 days, according to DFSS spokesperson Bryan Berg. In a statement, Berg wrote that the shelter grievance system is “vastly more responsive and effective in addressing the needs of our residents than it was at the inception of the mission.” Berg is no longer with DFSS.

The Investigative Project and Borderless have been unable to independently corroborate these improvements. The Office of Emergency Management and Communications, which maintains grievance records, denied a public records request for more recent grievance records. That denial is under review by the Illinois Attorney General’s Public Access Counselor.

Many Complaints, Little Action

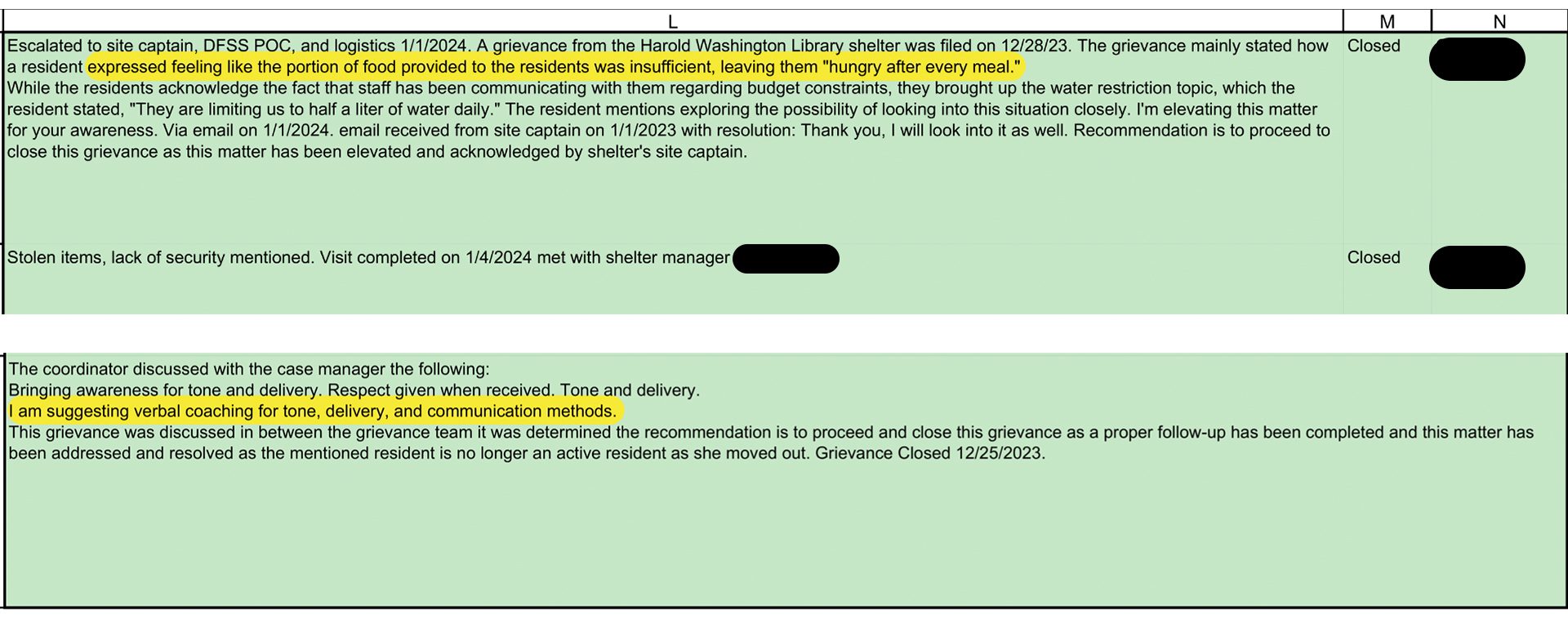

The grievance data reviewed by the Investigative Project and Borderless tell a different story. DFSS employees identified themselves as responding to just 29 of 244 grievances filed from the city’s migrant shelters between June 2023 and early January 2024, records show. The remainder of the grievances were marked as being resolved by an assortment of Favorite contractors, including shelter managers, site captains and project managers.

Nearly two of every three complaints identified some form of staff misconduct, WBEZ first reported.

Records show that over the six-month span, response to complaints was inconsistent and slow, with an average time of 35 days.

Favorite contractors monitoring the city’s grievance portal rarely recommended disciplinary action for staff accused of misconduct, suggesting a “corrective action” in just 24 of the 215 cases Favorite investigated.

One of those staff was the shelter manager of the Super 8. Migrant parents accused him and other staffers of limiting kids’ access to water, barring donations of clothing and threatening families with eviction. Records indicate that the manager closed out earlier grievances. (The Investigative Project and Borderless are not naming the manager because he could not be reached for comment.)

But in mid-December, one of the city’s newly onboarded grievance counselors — another Favorite contractor — reviewed the grievances and recommended “corrective action” for the shelter manager and the project manager for “failing to communicate with residents in a professional manner” and not ordering enough food for shelter residents.

Only a handful of the records indicate what corrective action was recommended or who administers discipline. However, those records show incidents and discipline being handled with little or no city intervention.

One example: A mother in a family shelter in Hyde Park wrote that after she asked for a glass of milk for her young child, she was mocked by a project manager and other staff over her requests for milk and told to take off her sweater. In her grievance, she asked for help pressing charges against the staff.

An investigation by Favorite contractors found that the project manager’s actions constituted a “potential abuse of authority” and a “serious matter that cannot be ignored.” Several weeks later, according to the grievance notes, other Favorite supervisors gave those staff members a “write-up” and a “counseling” session. Records indicate the investigators called and sent several emails to the mother but did not speak with her before closing the complaint.

Favorite contractors did recommend terminating staff once in response to allegations of a staff person yelling at a child. In one other case, city officials recommended terminating a security guard over allegations in grievances that he was having a relationship with a resident in his shelter. In another case, Favorite contractors recommended that a supervisor with eight complaints be transferred to another shelter after identifying a “lack of professionalism and respect” that was “interfering” with shelter operations.

The remainder were closed without recommendations for further action.

DFSS did not respond to questions about specific grievances or disciplinary procedures. “DFSS is encouraged by the fact that shelter residents have and continue to engage with our resident grievance process,” a department spokesperson wrote in a statement. “It means the process is being clearly communicated across the system, shelter residents feel comfortable raising their concerns and feel comfortable doing so.”

But, experts say that oversight in the shelters shouldn’t be dependent on people filing complaints. “The number of actual complaints was probably 10 times that amount,” said Hallett, the director of the Immigrants’ Rights Clinic. “But you have a population who doesn’t speak English, who may be moving from shelter to shelter, so may not be invested in complaining about a particular shelter, who may not have the wherewithal or the time or the resources to file a complaint.”

Favorite did not respond to the Investigative Project and Borderless’s findings or specific questions about its grievance policies. “Favorite temporary staff are subject to Favorite’s internal HR policies, and Favorite temporary staff help support and implement the City’s resident grievance processes,” Driver, Favorite’s senior vice president, wrote in the emailed statement. “Favorite is committed to continuous quality improvement and is constantly reviewing its policies and procedures to enhance the resident and staff experience.”

Staff Fear Retaliation

Grievance data released reviewed by the Investigative Project and Borderless included at least 10 complaints likely to have been filed by shelter staff. Most concerned supervisors’ treatment of them or the residents under their care, records show.

For example, one grievance came from a staffer assigned to serve food, who noticed that a batch of chicken smelled rotten. A manager told staff to wear gloves and put the food out as is, the staffer alleged. “Not even to animals would we serve rotten food,” they wrote in the complaint. “Would [the project manager] eat rotten food?”

The Investigative Project and Borderless interviewed 11 current and former shelter staffers who worked for Favorite and GardaWorld about their experiences working in the shelters. All of them spoke on the condition of anonymity because they were contractually barred from talking to the press without permission or feared it could cost them future work opportunities. Most worked contracts in federal shelters for unaccompanied migrant children before taking work in Chicago.

Three said they left the job over concerns about how the shelters operated. Three other workers said their contracts were not renewed after they brought up issues they encountered with shelter operations or with coworkers.

Before the city launched its web-based grievance portal in June 2023, shelters distributed paper grievance forms to give to residents, said Jordan, a Favorite case manager who started working for the city-run shelters that January. The Investigative Project and Borderless are using a pseudonym for the worker, who asked that their name not be used out of fear of being denied future contract work in migrant shelters.

“A lot of residents would want to do grievances, and they’re like, ‘Nothing ever happened, do they even read this?’ ‘Who can we talk to?’” said Jordan. “I didn’t know how to explain that we were just stuck there, that everything would stop at the shelter manager. Nothing would proceed after that.”

Read More of Our Coverage

The creation of a web-based portal that allowed anonymous submissions alleviated some of Jordan’s concerns about residents’ grievances.

However, the city’s grievance portal was designated for residents, not staff. DFSS’ Gilling acknowledged that staff could have filed some grievances via that portal, because it could be accessed by a readily available QR code. In an email, Gilling wrote that the “most direct and effective way” to address concerns would be to reach out to their supervisors. But Jordan said that without a formal grievance system, they and their coworkers continued to worry about grievance response and potential retaliation.

Some of the Favorite contractors working as supervisors or grievance counselors worked directly in the offices of DFSS and OEMC and were given city email addresses, records show. Jordan said that caused confusion when reporting problems. “The people that I was talking to [about issues in the shelters], I thought were from the city,” Jordan said. “But I don’t even know if I ever got to the city. We didn’t know who we were talking to.”

After submitting a complaint about poor shelter leadership, Jordan said that a supervisor told them to monitor quarantine rooms in addition to their usual caseload of more than 40 families. The quarantine shift started three hours before their case management shift.

Jordan quit in October 2023.

“The way things were being handled [in the shelters] was not appropriate,” said Jordan, who previously worked in federal shelters for unaccompanied migrant children. “I had never worked under staff that was just so unqualified to be in their role.”

“Favorite just failed as a company to its client and to its staff,” a second contractor told the Investigative Project and Borderless. “Many good staff left that really wanted to make a difference, but they were pushed out.”

City Leans on Favorite

Favorite Healthcare Staffing is one of three staffing companies that has supported Chicago’s migrant response since 2022.

The city first signed a contract with Favorite in September 2022 to staff shelters for migrants, shortly after Texas officials announced that they would send asylum seekers to Chicago, among other cities.

Colorado-based Jogan Health staffed makeshift shelters in hotels across Chicago and the suburbs on behalf of the Illinois Department of Human Services starting in September 2022, records show. The company, which was founded the year before, was a subcontractor of state crisis response vendor Innovative Emergency Management.

After launching an emergency rental assistance program for asylum seekers, the state closed those shelters in April 2023. That funding “eliminat[ed] the need” for state-run shelters and staffing services, a spokesperson for IDHS said. Later that year, IDHS reversed course and announced plans to open more shelters, this time using the services of security contractor GardaWorld.

GardaWorld has previously staffed migration facilities, including federal shelters for children arriving at the border unaccompanied. Favorite has provided staff for 10 immigration facilities since 2012, including federal shelters for unaccompanied minors, according to an internal document submitted to the City Council’s Committee on Immigrant and Refugee Rights in early 2024. Jogan did not advertise shelter staffing or immigration experience and the company did not respond to requests for comment.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, Favorite developed a reputation as a company that could remedy large staffing gaps in a pinch. The staffing agency signed more than $1 billion worth of contracts to staff developmental facilities, senior housing for veterans and even prisons throughout Illinois.

Both Favorite and Jogan had recent run-ins with labor and employment law, however. In 2020, the U.S. Department of Labor ordered Favorite to pay back more than $3 million in unpaid wages to contracted employees in Florida. In September 2022, the Colorado Department of Labor and Employment issued a citation to Jogan Health for its “willful” failure to pay overtime wages totaling more than $7,000 to a contractor working at a COVID-19 vaccine site, according to public records obtained by the Investigative Project and Borderless.

As the rate of migrants sent to Chicago has fallen, the local shelter system has shrunk. Earlier this year, Favorite managed more than two dozen shelters. Now, 12 city- and state-funded shelters are hosting around 4,400 migrants, according to the most recent city data. Ten of those are operated by Favorite and three by IDHS and GardaWorld. Earlier this year, the city transitioned two shelters from Favorite to local nonprofit management. The city continues to use Favorite contractors to manage its grievance system, DFSS confirmed.

Read More of Our Coverage

Residents in shelters operated by other companies have also filed grievances about shelter conditions, according to records obtained by the Investigative Project and Borderless.

In the first half of this year, migrants at a state shelter staffed by New Life Centers and GardaWorld in Little Village submitted 32 unique complaints about conditions and staff conduct. One staff member also filed a grievance. That shelter closed down in early November.

The records did show the date of submission and the outcome for each complaint but not the date of closure.

However, records do show that contractors fired by Favorite were rehired by GardaWorld to work in the shelter, which is located in a former CVS store on Pulaski Road.

One of the contractors, a Favorite security guard, was recommended to be fired in December 2023 after two complaints were filed alleging that he was having an inappropriate relationship with a resident, records show. Three months later, that security guard had a new position at the Pulaski shelter where a female resident complained that he entered her room without permission and started commenting on her physical appearance.

“Having a worker like him is scary,” the resident wrote in the grievance. Within three days the security guard was fired from the Pulaski shelter, according to the grievance file notes.

“IDHS takes the safety of all shelter residents seriously and prioritizes the dignified treatment of all,” the agency wrote in a statement. “IDHS is also constantly reviewing and evaluating its shelter policies and operations to best serve its residents and maintains open communications with the City of Chicago.”

When asked about the grievance process in state-run shelters, both IDHS and GardaWorld pointed to the city. IDHS uses the city’s grievance system, spokesperson Daisy Contreras confirmed. That means that all resident grievances from state-funded shelters also go to the Favorite contractors responsible for reviewing and responding to grievances in the city shelters. GardaWorld has no “visibility into either the grievances or the process,” a spokesperson for the company wrote.

GardaWorld did confirm that one of the two contractors rehired after dismissal from the city shelters has since been terminated. Both IDHS and GardaWorld declined to comment on specific grievances.

Life Beyond the Super 8

Reina Isabel Jerez Garcia said she never heard anything from the city or Favorite contractors about the grievances she and other parents filed at the Super 8 shelter, even after grievance counselors determined that shelter staff were responsible for shortchanging residents on meals.

Several weeks later, in January 2024, Jerez said the shelter manager gave her and her 17-year-old son a week to leave Super 8. She said that staff had written her up for violating a shelter rule prohibiting parents from leaving their kids unattended. She felt that the write-up was retaliation for her role in organizing and submitting grievances. “They were throwing people out in the streets in winter,” Jerez said. “This was inhumane treatment.”

At the time, Jerez was the only support and source of income for her and her son. Her husband was still traveling toward Chicago with their two younger sons. While she waited to receive federal work authorization, she had found under-the-table work tutoring children.

“There’s a lot of legal holes,” said Benjamin Ramos Anderson, a social worker and volunteer at the Super 8. “These people are vulnerable, and their rights are not being protected, and violations against them are not being investigated.”

Ramos Anderson helped Jerez file her grievances and said he heard complaints from other residents, including one about the shelter manager stopping a parent and child in quarantine from leaving to seek medical care.

Ten months after being evicted from the Super 8, Jerez and her family are settled on the city’s far South Side. A shelter worker helped her pin down an apartment in January, and she used the state’s emergency rental program to put down three months’ rent. Her husband and two younger sons joined them earlier this year, as have her nephew and his small family.

She tried to hang on to the work she had found near the Super 8. However, in February when she traveled north to pick up her pay, her boss sent her to a new address, and a man she had never met assaulted her, she said. She filed a police report and a restraining order against the man and was too scared to return to her job.

Jerez says she hopes to build on her advocacy work in Colombia by creating an organization to support migrants here in Chicago and ensure their humane treatment in shelters.

“They’re not overseeing them, they’re not inspecting [the shelters],” Jerez said. “I’d like to propose that the City of Chicago meets with residents in the shelters every month to ask them, ‘How are you feeling?’ ‘How are they treating you?’”

“If I knew the language, I would say this all in English, truly,” she laughs. “I have so many things to say … I’ll have to spend a year studying to prepare myself to say it all.”

Contributing reporting by Jonathan Torres, Katrina Pham and Martha Contreras.

This investigation was supported with funding from the Data-Driven Reporting Project. The Data-Driven Reporting Project is funded by the Google News Initiative in partnership with Northwestern University | Medill.