Fighting for a chance to stay, many immigrants wade alone through backlogs and attorney shortages that plague the immigration court system.

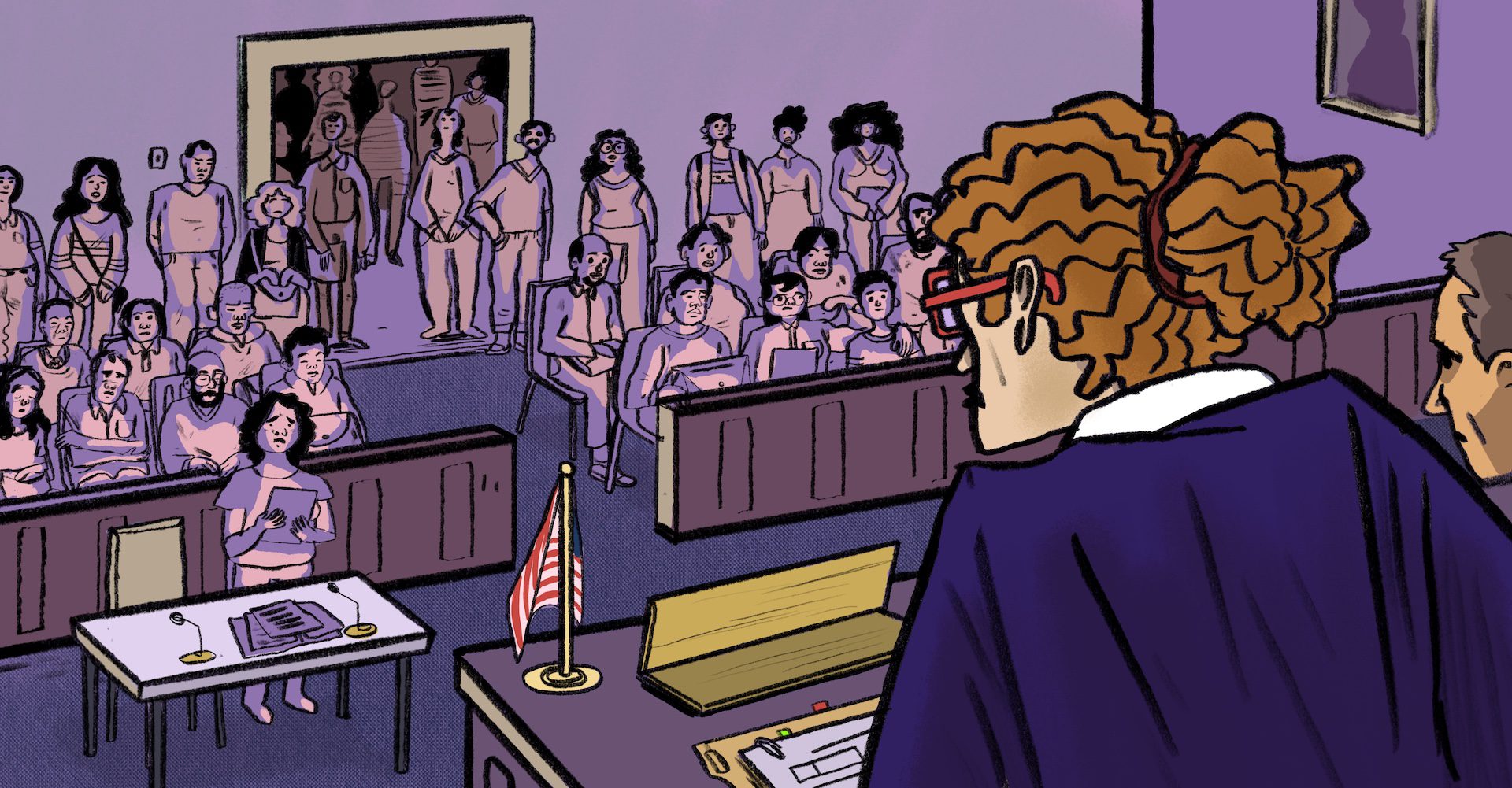

With a pile of documents spread out in front of her, Auscena Rodriguez begins to explain why death awaits her in Honduras.

And because she doesn’t have a lawyer and time is not on her side, she will be her own lawyer, she tells a judge in Chicago’s Immigration Court.

“I fear that my life and my children’s lives are in danger so I will present my evidence,” she explains in hurried Spanish.

News that puts power under the spotlight and communities at the center.

Sign up for our free newsletter and get updates twice a week.

Why doesn’t she have a lawyer? The judge asks.

She had a lawyer, but he was “negligent,” and since she cannot afford another one and can’t leave her job to find a new lawyer, she is on her own, she says.

She is desperate because drug traffickers in La Ceiba, Honduras, where she was a veteran police officer, tried to kill her and her children, and their threats haven’t stopped, she says.

“I received a message that [the gangs] are going to kill my [two] children, but I don’t have a way to bring them here,” she adds, wiping a tear away.

Before she goes any further, the judge says she will have more time to find another attorney. Outside the courtroom, she vows to find one but admits she is unsure how.

Her worry is a common one nowadays in Chicago’s Immigration Court — a scene that plays out in many other courthouses across the U.S.

A scarcity of immigration attorneys for immigrants in Chicago amid a wave of new arrivals has made finding a lawyer an insurmountable task. And the failure to obtain one can mean the difference between starting a new life in the U.S. or joining the millions of undocumented immigrants in the country who live in limbo, forever at risk of deportation. Or, worse yet, returning to the dangers they fled.

Chicago’s Immigration Court

On the 15th floor of a sleek downtown office building, the Court fills up in the morning with single men and women, mothers and fathers and their children, sitting in a nervous hush. They are mostly Spanish speakers, but they also come from everywhere and speak many dialects and languages.

Before the sessions begin, they gather around and try deciphering the information on the flashing digital information boards that tell them which courtroom they should be in. Some study long-printout lists with more up-to-date information on court assignments. These lists show who has attorneys, and usually only a handful do.

As hearings begin, there’s the feeling of being in a traffic court rather than anything else, as one immigration judge remarked some years ago.

That’s because preliminary hearings quickly zip by, and immigrants shuffle in and out of the courtrooms, their names and cases tacked on to the court’s growing backlog. But the process can come to a halt if an immigrant says they want to defend themselves and risk their fate. Suddenly, the court is no longer a traffic court but a place where someone’s life can be on the line.

Read More of Our Coverage

Chicago’s Immigration Court is one of the nation’s largest courts, handling proceedings for Illinois, Indiana and Wisconsin. It’s where immigration court judges, in most cases, have the final word on whether someone can stay or be deported.

Reflecting the nationwide trend of courts slammed by the thousands of immigrants arriving at the nation’s borders, the court faces a massive increase in backlogged cases. As of March, the backlog in Illinois had grown to 235,200 — up from 47,462 in 2020, according to TRAC.

In most of those cases, people are fighting on their own to stay in the U.S.

Only one out of four immigrants had a lawyer among the 211,096 persons whose cases were backlogged in Chicago as of Dec. 2023, according to research done by the Transactional Records Analysis Clearinghouse (TRAC) at Syracuse University.

That put the Chicago court among those with lower rates of representation. In comparison, the rate was 49% in California and 44%in New York state.

But having a lawyer can be essential to navigating the court system — from knowing when their court date is, understanding how to update their address, knowing what immigration relief forms they apply for, as well as ultimately having someone to represent them and plead their case in front of the judge.

According to the National Immigration Forum, someone’s chance of winning their asylum case is five times higher if they have an attorney to represent them.

“If people have the information to make informed decisions about what opportunities are available for them under the law, the system works better,” said Lisa Koop, the national director of legal services for the Chicago-based National Immigrant Justice Center.

Band-Aids on Bullet Wounds

On a bench in one of the crowded waiting rooms, Malick Sai, 28, is leaning forward, talking with a young Haitian couple sitting stiffly waiting for their hearing. An immigrant from Senegal, he is talking in French with the couple, sharing some basic details about how the courts work.

He is not here for himself, however, but comes every so often with a friend, driving up from Indianapolis, so they can help immigrants, he explains. He is a green card holder.

“If they don’t have a lawyer, they are condemned,” he whispers in the room, where there’s rarely a loud noise, except for a baby’s cry. “And most of the time, they don’t.”

“You really need to get a lawyer,” immigration court judge Kaarina Salovaara said for the nth time on a very busy day. Almost everyone who stood before her offered the same answer — how could I possibly afford a lawyer?

The problem is that attorneys can cost hundreds to thousands of dollars in Chicago, according to Chicago-area immigration law group, Scott D. Pollock & Associates, P.C. The other problem is that panicked immigrants may take any attorney, whether or not they know their qualifications.

Compared to other states, Illinois has a network of pro bono immigration counselors and attorneys available through long-standing community organizations across the state. The Resurrection Project (TRP), a Chicago-based community and advocacy agency, heads the immigrant efforts of the Illinois Access to Justice effort that supports these organizations.

TRP historically provides long-term case management and support for immigrants in Illinois. But with the increase in demand for legal services, TRP’s help for new arrivals has shifted mainly toward their immediate needs, including legal consultation, applying for asylum or changing their venue to the Chicago immigration court, says Immigrant Justice Legal Clinic Director Katherine Greenslade.

“There are so many people seeking asylum that we don’t have capacity to take all of those cases and do that full scope representation where we provide them with a case manager and ongoing support,” Greenslade said.

As an alternative to asylum representation, TRP has been hosting free asylum workshops where attendees can receive help filling out asylum applications.TRP also provides consultations by appointment, but those can fill up in minutes, Greenslade added.

“I feel like it’s just putting a Band-Aid on a bullet wound,” Greenslade explains. “It’s addressing their immediate needs, but it’s not providing a long-term solution.”

Without a lawyer, immigration court can be a maze with no exit.

“It’s almost impossible for someone to navigate the system themselves,” says attorney Shannon Shepherd in Chicago. “It is tough enough with legal training [to] do it.”

For immigrants with limited or no English, the challenges are many.

If they have moved and missed the mail about a court hearing or didn’t understand the language in the notice, that could ultimately trigger court-ordered deportation. Shepherd says she has seen cases where immigrants didn’t know they faced a deportation order until they were stopped by police.

Nationally, the number of immigrants who were deported for failing to appear in court spiked markedly in 2023, reaching 159,379 — almost doubling since 2020, according to government reports. Of the 5,058 immigrants deported in Illinois in 2023, 68% had failed to attend court hearings, TRAC figures show.

A young Guatemalan mother sitting with two active children, awaiting a hearing, is one of those who says she lost contact with courts since she began moving around the Midwest in 2019. But now, she says, she has caught up with the court.

And then there are those who received court notices, known as a Notice To Appear, or NTA, that had the wrong or inadequate information. Immigration court judges nationally threw out 200,000 cases between 2021 and 2023 because of flaws with these notices, according to TRAC.

Read More of Our Coverage

Judges in Chicago’s court threw out 5,040 of all cases, or 11%, during this time. Only 9% were renewed by the court within a year. A dismissed case can suddenly plunge someone into limbo since they need to have a new case filed if the government doesn’t refile it. But that’s not an easy effort for an immigrant without an attorney.

Then, there are cases that are delayed for different reasons. Since 2022, a Guatemalan immigrant, who is a client of Shepherd, has had their court hearings delayed three times for a lack of a translator, says Shepherd.

Lauren Aronson, head of the Immigration Law Clinic at the University of Illinois in Urbana-Champaign — one of few resources for immigrants in downstate Illinois — has a 15-year-old client who entered the U.S. in 2022. He has yet to receive a court date. That doesn’t matter for him, however, because he has other legal options not available to everyone, she explains.

There are two sides to the reality of long delays in criminal court for immigrants.

For those unlikely to win their case, a delay means more time to work and live in the U.S. But for those hoping to rescue family members from danger, like the former Honduran police officer, a delay can be deeply worrisome. As of March, the average wait in the Chicago court for an individual hearing, which is often the final hearing, was just over 1,000 days, according to TRAC.

How to fix the problem

Koop, the immigration legal advocate with NIJC, said the system requires change at all levels, noting the backlogs are not just a problem of the courts.

“We need immigration legal reform,” she says. “We need things that are outside of the control of the city and the state to happen to alleviate the pressure on the system.”

Greenslade, of the Resurrection Project, explained how some people in removal proceedings may be waiting to hear back on applications for relief through USCIS, but because many of those applications face yearslong backlogs as well, people have to wait years for any sort of immigration relief.

“There are backlogs not just in court, but across all different parts of immigration — and there are people in removal proceedings who may be able to have their case terminated and end their proceedings if they could ever get a grant on something else,” Greenslade said.

“The court backlog would clear itself a bit if some of these other parts of immigration weren’t also backlogged.”

A system where everyone in immigration court, regardless of their status, could have access to free representation, she adds, could not only help people navigate the system better, but could also help more people win their cases.

“I think we have to move towards a system where, whether detained or non-detained, folks who are in removal proceedings and cannot afford counsel are provided an attorney” just as those in criminal proceedings in Cook County or the Federal courts are, she says.

Until then, more and more immigrants will face an unforgiving system on their own, advocates say.

Unlike the men in the three cases in front of her, who glumly tell the judge they couldn’t find a lawyer; Jesika Pino tells the judge she has the same problem. But she adds with a warm and assuring smile that she will do her best.

Immediately outside the courtroom, however, Pino, a small, soft-spoken woman who worked with children in Venezuela, breaks into heaving sobs that she doesn’t seem capable of stopping.

How, she asks out loud, can she find a lawyer when she works every day at a factory and then just earns enough to live? And what can she do if she knows nobody, “ni una sola amiga,” “not a single friend,” no family members, nothing?

But she is not going to go back to live under the Maduro government, she says defiantly in Spanish. Nor, she says, will she give up after coming all the way by herself, and especially after crossing the jungle, and points down at bruises on her feet.

That jungle is the Darien Gap, a stretch of dense jungle between Colombia and Panama, where immigrant travelers have been robbed, raped, and lost their lives. In the last few years, it has been a lethal funnel for immigrants headed north from South America.

“I have no choice,” she says, catching her breath. “I have to find a lawyer.”

Her lament is a common one here.

Here are links to organizations providing services, including legal support to immigrants.

- Illinois Department of Human Services

- Immigration Advocates

- Illinois Access to Jusice

- University of Illinois, Law Clinic, Urbana-Champaign

- American Immigration Lawyers Association (AILA)

- How to Find an Immigration Attorney, U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement

- List of Pro Bono (free ) lawyers by state, U.S. Department of Justice

- U.S. approved legal organizations nationally, U.S. Department of Justice

- U.S. approved legal representatives nationally, U.S. Department of Justice