Photo by April Alonso for Borderless Magazine/Catchlight Local

Photo by April Alonso for Borderless Magazine/Catchlight LocalA new unit within the Cook County public defender’s office wants better representation for noncitizens clients at risk of being deported.

Alejandra Cano thought she was in the clear.

It had been five years since she got sober after a decades long struggle with drug addiction. She racked up several misdemeanors when she was using, mostly for shoplifting. But that was another life. In this one, Cano, 46, was a working single mom who lived in a comfortable first-floor apartment on the West Side of Chicago with her two teenage sons. And after almost 20 years of not seeing her dad or her homeland, Cano decided to fly to Chile in August 2019.

“I still had my green card. I had no reason to worry,” Cano said.

She was wrong. Upon her return from Chile, U.S. Customs and Border Protection agents at O’Hare International Airport pulled Cano aside. Her rap sheet had popped up when they ran her fingerprints at the customs checkpoint, even though her last conviction was five years earlier. After hours of waiting alongside other noncitizens, an agent took away Cano’s green card. The government is now seeking to revoke her legal status and deport her.

Cano is one of thousands of people — including undocumented immigrants, visa holders, and lawful permanent residents — who go through deportation proceedings in Chicago each year, according to federal immigration court data collected by Syracuse University’s Transactional Records Access Clearinghouse. Many end up there via the criminal justice system. Not only do arrests draw the attention of U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement, certain criminal convictions can also trigger a deportation case. That includes offenses that, for a citizen, might mean only a court fee or short jail sentence. But noncitizens can end up being punished further with deportation — what’s known as a “collateral consequence,” akin to the loss of voting rights and other civil penalties that get tacked on to criminal convictions.

Alejandra Cano and her high school son Nico Ortiz outside their home Tuesday, March 16, in Evanston, Illinois. April Alonso for Borderless Magazine/CatchLight Local

The Cook County Public Defender’s Office estimates that its staff represents hundreds of noncitizens in felony cases at any given time — all of which could result in such collateral consequences. A new immigration unit within the public defender’s office aims to disrupt this conviction-to-deportation pipeline. Working with public defenders, prosecutors, and community groups, the unit will ensure that noncitizens are warned when a plea deal could cost them their status and their home.

While Illinois has long required defense attorneys to do so, Cano said her Cook County public defenders never did — an oversight that’s all too easy under the current system, according to several immigration and defense attorneys in Cook County who spoke to Injustice Watch and Borderless Magazine.

Three of the five misdemeanors that Cano pleaded guilty to between 2005 and 2013 were for retail theft, making her deportable under federal immigration law.

Had she been warned of this, Cano said she would’ve thought twice before boarding a plane. “At the very least, I would’ve hired an immigration lawyer to help me figure out what was going on,” she said.

While the scope of the new immigration unit is currently limited to advising public defenders, county officials say they ultimately want to provide free immigration attorneys to more immigrants facing deportation in Chicago. But fulfilling this promise will require changing state law, as well as overcoming the fiscal constraints that have hampered the public defender’s office for decades.

A deportable offense

Immigration issues loom large within the court system in Cook County, where one in five residents was born in another country. Most of those residents live in metro Chicago, which is home to 480,000 green card holders and an estimated 460,000 undocumented immigrants, according to a recent study published by The Chicago Council on Global Affairs.

It’s unclear how many noncitizens are facing criminal charges in Cook County; the circuit court doesn’t track a defendant’s immigration status. An internal survey conducted last year found that Cook County public defenders collectively represented approximately 700 noncitizens from more than 80 different countries in open felony cases.

“All those folks face immigration consequences stemming from that criminal case,” said incoming Cook County Public Defender Sharone Mitchell Jr., who takes the reins April 1.

When it comes to which crimes could get a noncitizen deported, immigration law is both exact and vague. Deportable convictions generally fall under two categories: aggravated felonies — a laundry list of more than 30 types of offenses, including drug trafficking, filing a false tax return, and failing to appear in court — and crimes “involving moral turpitude.”

The latter category is purposely vague; even the Justice Department has said the term is “difficult to define with precision.” Murder and other violent acts are included, but so are nonviolent crimes, such as embezzlement, fraud, forgery, and theft. In the absence of a clear definition, immigration courts make determinations on a case-by-case basis, informed by relevant case law and state criminal statutes.

Download a shareable PDF of an immigration lawyer’s tips for noncitizens in criminal court.

To make matters more complicated, alternative sentences, such as probation, restitution, community service, and drug rehabilitation — options regularly sought out when looking to cut a deal with prosecutors — may also put a noncitizen at risk for deportation.

For these reasons, anticipating collateral immigration consequences can prove difficult, even for the most informed criminal defense attorneys. Nevertheless, in the 2010 Padilla v. Kentucky ruling, the U.S. Supreme Court held that, under the Sixth Amendment, attorneys have an obligation to ask clients about their citizenship status and inform them whether a plea deal carries a risk of deportation.

While the mandate from the courts is clear in theory, multiple Chicago immigration attorneys told Injustice Watch and Borderless Magazine that, in practice, gaps in the system frequently leave immigrant clients unprotected from collateral consequences.

Kate Ramos, a supervising attorney at the National Immigrant Justice Center, a Chicago-based nonprofit, is representing Cano in her deportation proceedings. Cano isn’t the only client who landed in deportation proceedings following a plea deal, Ramos said: “A lot of our clients come in and tell me … they were not aware of the consequences.”

Having a dedicated immigration unit in the public defender’s office could matter, according to Ramos. “Public defenders are not immigration attorneys,” she said. “They’re looking [out] for the good for their clients from a criminal standpoint, [and] that’s why it’s important to have an office that can really focus on both.”

Before the immigration unit got up and running, public defenders consulted with immigration lawyers on a case-by-case basis.

But Angela Kilpatrick, the head public defender at Cook County’s Bridgeview courthouse, said sometimes it’s hard to square the most immediate relief for a client — taking a plea deal to get out of custody, for example — with the potential impact to their immigration status down the line.

Having an in-house immigration lawyer to advise public defenders on these concerns will go a long way toward creating a “360-degree, bubblewrap approach on how we do [criminal] defense,” she said.

Hena Mansori, the head attorney of the new immigration unit in the Cook County Public Defender’s Office, near her home March 22, on the Northwest Side of Chicago. April Alonso for Borderless Magazine/CatchLight Local

Heading the unit is longtime immigration lawyer Hena Mansori, who worked at the National Immigrant Justice Center for more than a decade. Since January, she has been busy training dozens of Cook County public defenders via Zoom and developing a new intake system to identify and track cases where public defenders are representing noncitizens. The system will be protected by attorney-client privileges, so clients won’t have to worry about being targeted by ICE.

The immigration unit is still a team of one, but the county plans to hire two more immigration lawyers and a case manager to join Mansori later this year, she said.

Mansori also hopes to put knowledge directly in the hands of immigrant communities through information sessions with community partners. At a virtual training with the Chicago-based United African Organization in November, Mansori explained how a criminal conviction may lead to deportation, and she fielded questions from an audience of about 40.

“[The immigration unit] is critical for our community,” United African Organization Programs Director Fasika Alem said. “Like all other Black people, the interaction of African immigrants with law enforcement is greater because we live in communities that are overpoliced.”

While Black immigrants make up about 7% of the total noncitizens residing in the U.S., they made up more than 20% of immigrants facing deportation on criminal grounds between 2003 and 2015, according to an analysis of federal immigration data by New York University School of Law’s Immigrant Rights Clinic.

Alem’s group is part of the coalition of activist and civil rights groups that pushed to establish the immigration unit. While she applauds its launch, she said officials shouldn’t lose sight of what she thinks is the main goal: universal representation for all immigrants in need of a lawyer in Chicago.

“We’re going to continue to push for that. The sooner, the better,” she said.

A lawyer for every immigrant

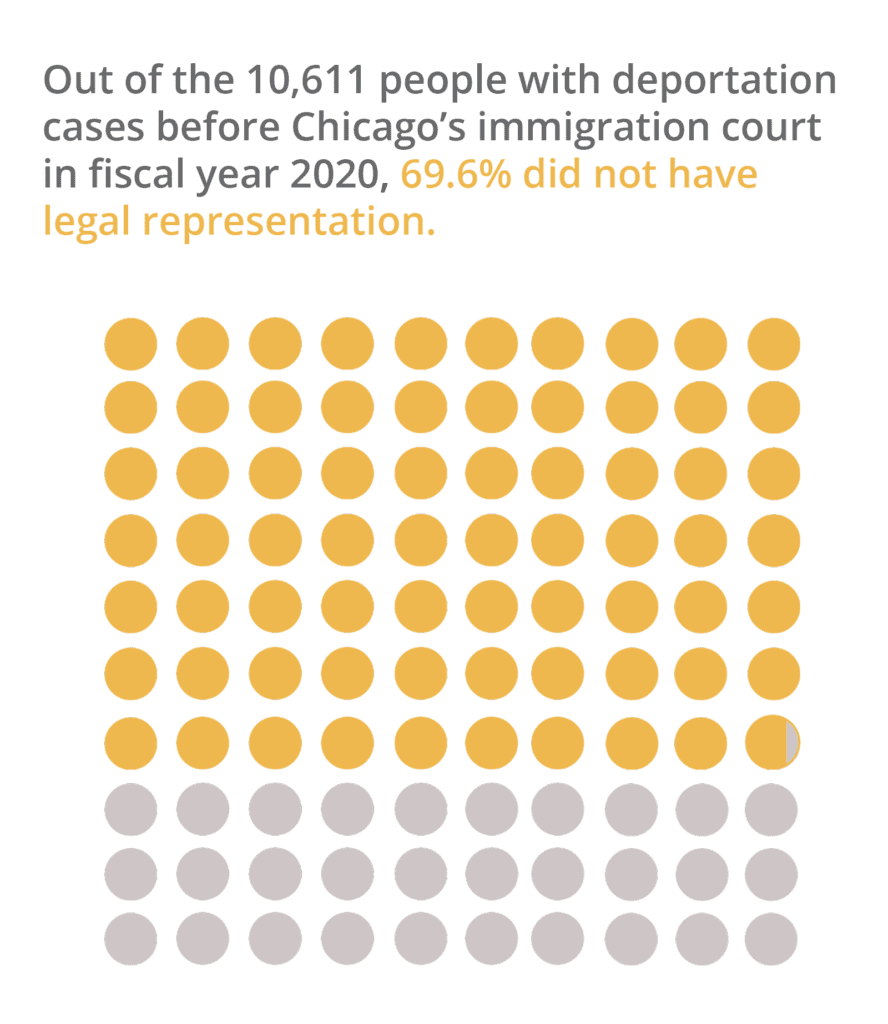

While the Sixth Amendment guarantees criminal defendants a right to a lawyer, that same right does not extend to immigration court. Last fiscal year, 66% of immigrants in deportation proceedings nationwide did not have a lawyer, according to Syracuse University’s Transactional Records Access Clearinghouse. At the Chicago Immigration Court, that figure was closer to 70%.

When immigrants facing deportation do have a lawyer, they are up to 10 times more likely to win their cases, according to an analysis by the Vera Institute of Justice. Several localities already provide at least some publicly funded immigration defense. New York guarantees universal representation in immigration court statewide.

Data provided by TRAC.Michelle Kanaar/Borderless Magazine

It’s unlikely that Illinois will follow suit anytime soon. The Cook County public defender’s office is currently pushing an amendment to an Illinois law that would expand who public defenders can represent to include noncitizens with cases before Chicago’s immigration court. The amendment passed out of an Illinois House committee in March.

Even if the measure succeeds, a lack of funding and personnel means that the county would still pick and choose which noncitizens get a lawyer. For the time being, the priority will be to provide immigration attorneys to defendants who are either currently represented by a Cook County public defender or have been in the past, according to Era Laudermilk, a legislative affairs deputy at the Cook County public defender’s office.

“Our goal … is to ensure that we’re providing the most services that we can and balancing the needs of the central functions of the office without robbing Peter to pay Paul,” said Mitchell, the incoming Cook County public defender.

That points to a larger concern for Xanat Sobrevilla, an organizer with Organized Communities Against Deportations, an immigrant rights group in Chicago. She worries that Cook County will not adequately fund the immigration unit or the public defender’s office writ large to properly do its job, as crushing caseloads have overburdened public defenders for years.

“If we can’t stop the over-policing of [Black and brown] communities, then we won’t stop more immigrants coming in contact with the criminal justice system,” Sobrevilla said.

Mansori hopes to see the county eventually invest in universal representation, especially given the financial and emotional impact that detention during deportation proceedings has on family members. But for now, defending cases in which immigration law is murky could have a broader impact in stopping collateral consequences. Where immigration courts must interpret, for example, which types of crimes involve “moral turpitude,” winning deportation relief in one case can “set a precedent that benefits many others as well,” Mansori said.

For her part, Cano is hopeful that more robust immigration defense in Cook County will mean that others won’t have to go through what she did. Cano’s case is still in limbo, as her hearing before an immigration judge was canceled because of the Covid-19 pandemic and has yet to be rescheduled.

Until she knows whether she can stay, Cano is taking it one day at a time.

“That’s something I learned in recovery,” she said.

Rita Oceguera contributed reporting. This story is part of the collateral consequences series, a partnership between Injustice Watch and Borderless Magazine to explore the criminal conviction to deportation pipeline in Cook County.