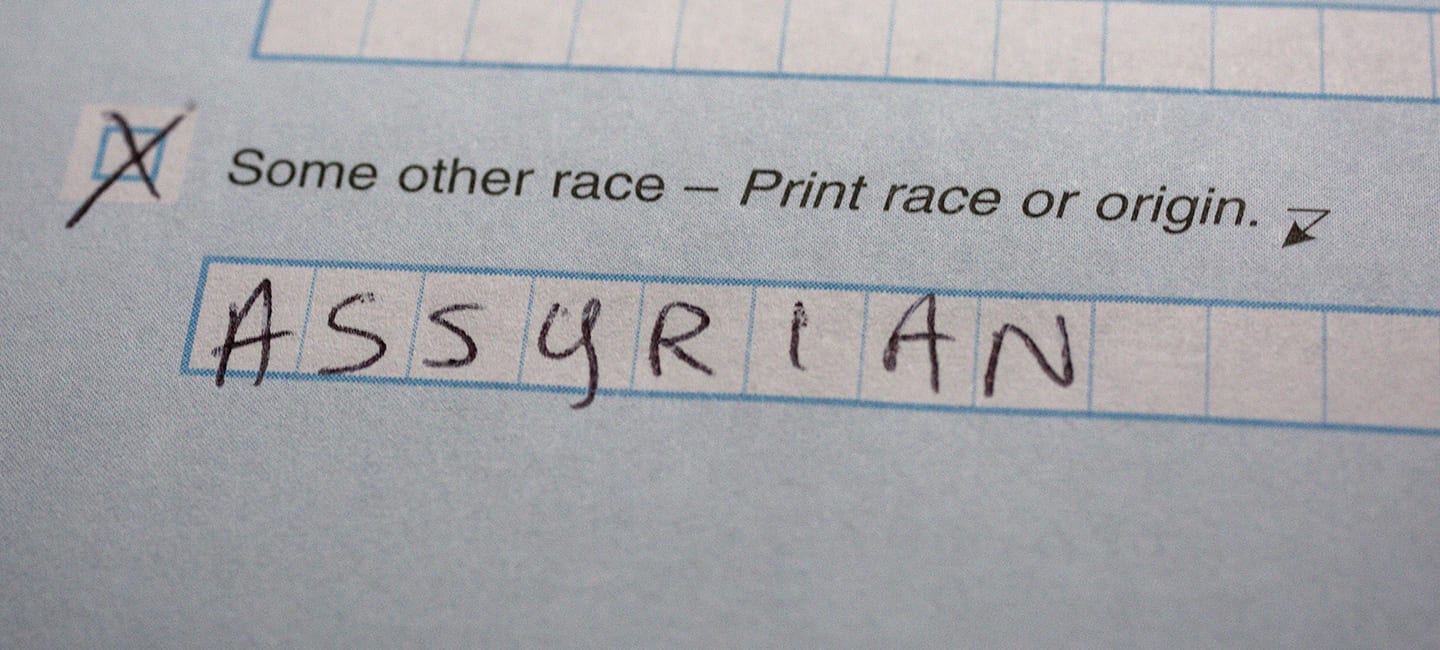

Local Assyrian leaders are encouraging community members to participate and write in ‘Assyrian’ as their race in this year’s census after massive undercounting in previous national surveys.

Above: Photo illustration. Michelle Kanaar/Borderless Magazine

Billy Haido was a one-year-old when he immigrated from Iraq to the United States in 1978. Witnessing the continued persecution of Christians in his homeland his father decided to seek asylum for his family in another country.

After moving Haido continued to speak his Assyrian language at home while also learning English and acclimating to life in the United States. He kept eating his ancestors’ food, like stews ladled on heaping piles of rice. He attended Easter celebrations and indulged in rich and creamy bowls of hareesa often served at his church. He listened to music from Assyrian artists Linda George and Sargon Gabriel.

When Assyrians celebrated Kha b’Nissan, the Assyrian New Year, in 1992 for the first time on Chicago’s King Sargon Boulevard, located on a stretch of Western between Peterson and Pratt, Haido was there front and center.

Haido lived and breathed a very distinct Assyrian culture, one passed down for thousands of years by his ancestors.

Yet, every ten years when he filled out the census he chose “white” as his race. This year, he says, that’s changing.

“Census 2020 is more than just filling out an online document and counting how many Assyrians are here. It will show us and the rest of the country that we can get organized and we can be taken seriously,” said Haido, co-founder of the local grassroots organization Vote Assyrian.

Assyrians are one of the indigenous, ethnolinguistic populations of modern-day Iraq. Their ancestral homeland is spread over Iraq, Iran, Turkey and Syria. Since the 2003 Iraq War, and more recent conflicts led by ISIS, Assyrians find themselves displaced both within and outside their homeland. Some estimate that 60 percent of Iraqi Assyrians have fled the country since the Iraq War began, according to PBS NewsHour.

The 2018 American Community Survey estimated there were 104,381 Assyrians in the United States. Yet, community leaders in Illinois believe there are closer to 100,000 Assyrians in the state.

Undercounts in both the U.S. Census Bureau’s 10 year headcount and yearly community survey are common in immigrant populations. But it may be exacerbated in Assyrian communities because of confusion over what to put as their race and fears about government persecution.

To avoid similar undercounts in this year’s census local Assyrian leaders like Haido are encouraging community members to participate and write in ‘Assyrian’ as their race.

Billy Haido, a co-founder of the local grassroots organization Vote Assyrian, pictured outside his home in Skokie, Ill. on May 4, 2020. Michelle Kanaar/Borderless Magazine

“The future of our existence in America is at stake. Not to sound too dramatic, but not having a country to fall back to, we have to know some details about our people in diaspora. We have to be proud to say who we are and not worry about repercussions. We aren’t the first immigrants in this country and certainly won’t be the last,” Haido said.

What makes a community ‘hard-to-count’?

Across the nation areas are broken up into census tracts. Equivalent to about 1,500 housing units or 4,000 people these tracts are used to analyze populations and their tendency to be counted. Tracts with the lowest levels of response are deemed “hard-to-count.”

Specific populations, including immigrant communities, historically have been or are at risk of being missed in the census at disproportionately high rates, according to government data.

One reason immigrants are undercounted are their concerns about the government. When a government agency shows up at their door to ask Assyrians questions it may trigger memories of detainment and unlawful interrogation similar to what happened under Saddam Hussein, Haido said.

“There’s a lot of fear, people not trusting their government even though [census] data is not given to any other agency. It starts triggering that old Middle Eastern mentality because they lived under dictatorships,” Haido said.

Assyrians hesitant to fill out the survey may not understand that a census miscount can mean disadvantaged communities don’t receive accurate levels of political representation in Congress and access to federal funding, Haido said.

Additionally, funding for senior care services, Assyrian language education, community program grants and Assyrian language services in hospitals, colleges and schools are all dependent on accurate census numbers.

In order to prevent under-counting again Haido’s group has been reaching out to community members and educating them on the importance of filling out their census form. With the support of the Assyrian National Council of Illinois and the Illinois Coalition for Immigrant and Refugee Rights, VA received a $109,875 grant from the state of Illinois to do census outreach.

Earlier this year, the group held an informational session for potential canvassers and ambassadors. The original plan was to hire canvassers to visit Assyrian homes in the Chicagoland area. But strategies have shifted as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic. While the goal remains the same the group has started to use remote phone banking to reach out to Assyrians asking them to fill out the census.

“Our refugee and immigrant population have become hard to reach as a result of COVID-19,” said Mary Oshana, Vote Assyrian’s executive director.

“We’re working with individuals that may not have access to the Internet, are facing job loss, and may not have the literacy skills to complete the census online or on paper. These are definitely challenging times not being able to reach our community in-person,” she said.

The group has also developed Assyrian and Arabic social media posts about filling out the census for families with Internet access. They’ve also held Facebook Live sessions to dispel myths and rumors about the decennial count, including rumors that responses could affect their social security benefits or citizenship status.

Assyrian American MMA fighter Beneil Dariush speaks to the Assyrian community about marking “some other race” and writing in “Assyrian” on the 2020 Census in a video posted about a month ago on Vote Assyrian’s Facebook page.

Atour Sargon, the first Assyrian elected to the Lincolnwood board of trustees, has been a strong advocate of the campaign. It’s especially important for older Assyrians to understand the importance of the census in providing political representation and directing federal funds to local schools and infrastructure, she said. For every person who is not counted in this year’s census, Illinois stands to lose between $1,400 and $1,800 in federal funding per year for the next decade, according to the Illinois census office.

“Since the census is only every 10 years and because the numbers were so low in 2010, we knew it should take precedence and be a priority for us,” said Sargon. “Growing up in this country, [we have] opportunities and resources that our parents, being new to the country, didn’t know about. So it’s really incumbent upon us to make sure we get accurate numbers this year.”

Not “White”

Joseph Hermiz, an Assyrian-American currently working on his PhD in Near Eastern Languages and Civilizations from the University of Chicago, agrees part of the challenge with accurately filling out the census comes from a generational gap.

“I think the census can be a little bit overwhelming for members of our community since a majority of them are immigrants,” says Hermiz. “My parents, for example, and I know many of my own friends, we’re all first generation. For many years our parents were the ones who completed the census and they were never very sure because ‘Assyrian’ isn’t an obvious option. It’s not one of the racial categories that are presented and a lot of times they may think that the question may actually be asking what their national origin is — Iraqi, Syrian, Iranian.”

The race category on the census is confusing for many Assyrians who, like other Middle Easterners, do not consider themselves white, Hermiz says.

And while categorically identifying as ‘Assyrian’ on the census speaks to issues of self-identity and visibility, doing so exists against the centuries old backdrop of racial ineligibility for U.S. citizenship.

The Naturalization Act of 1790 limited citizenship to “a free white person” having lived in the United States for two years. Amendments were passed over the years to provide inclusion for Native populations and people of African descent.

In 1915 a pivotal case came to the steps of the Supreme Court when George Dow, a Syrian immigrant, was denied naturalization. As Dow made his way through the U.S. legal system he successfully argued, “that the inhabitants of a portion of Asia, including Syria, were to be classed as white persons.”

Ultimately Dow was granted naturalization and Middle Easterners and North Africans across the nation began to identify as white. But as the political climate in the United States has changed, these old modes of identification no longer seem to accurately encompass the identity of Middle Eastern Americans.

“We’re starting to see the kind of futility of racial categorization and we’re stuck with these old models and categories. Assyrians in their native homelands don’t really associate themselves with being white,” Hermiz said.

“Generally speaking, they come from countries where they’re second class citizens for the most part. They don’t really have the privilege that many white people in the U.S. may enjoy compared to immigrant communities,” he said.

Currently, Assyrians and other people of Middle Eastern origin are not considered minorities under Illinois law. In addition to trying to get an accurate count of Assyrians in Illinois, the group is working with the American Middle East Voters Alliance PAC to get both Chicago and Illinois officials to recognize Middle Easterners as minorities.

“If we can get Middle Easterners on that list, it will give opportunity for our Assyrian business men and women,” said Haido. Many government projects set aside a certain amount of contracts for minority businesses. The City of Chicago, for example, has a goal of awarding 10 percent of the annual dollar value of non-construction contracts to minority-owned businesses.

All this makes this year’s census even more important, Oshana said.

“We will not have another opportunity for another 10 years to get an accurate count of Assyrians in Illinois. We need to make Assyrians more visible than ever numerically. This is an opportune and monumental time where we can leverage census data to lobby for more programs and services on behalf of Assyrian organizations,” Oshana said.

Have questions about the coronavirus and how to protect yourself from COVID-19? Read the CDC’s guide to the coronavirus here.