Camilla Forte/Borderless Magazine/Catchlight Local/Report for America

Camilla Forte/Borderless Magazine/Catchlight Local/Report for AmericaLo que hace décadas comenzó como oraciones silenciosas los viernes por la mañana se ha convertido en un movimiento más grande y ruidoso, a medida que los activistas se unen a un grupo de oración de larga trayectoria para exigir la liberación de los detenidos.

Al salir el sol en los suburbios de Broadview, Illinois, el abogado de inmigración Royal Berg se sitúa en el centro de una pequeña congregación a pocas cuadras del centro de procesamiento del Servicio de Inmigración y Control de Aduanas de Estados Unidos (ICE, por sus siglas en inglés), ubicado en 1930 Beach Street.

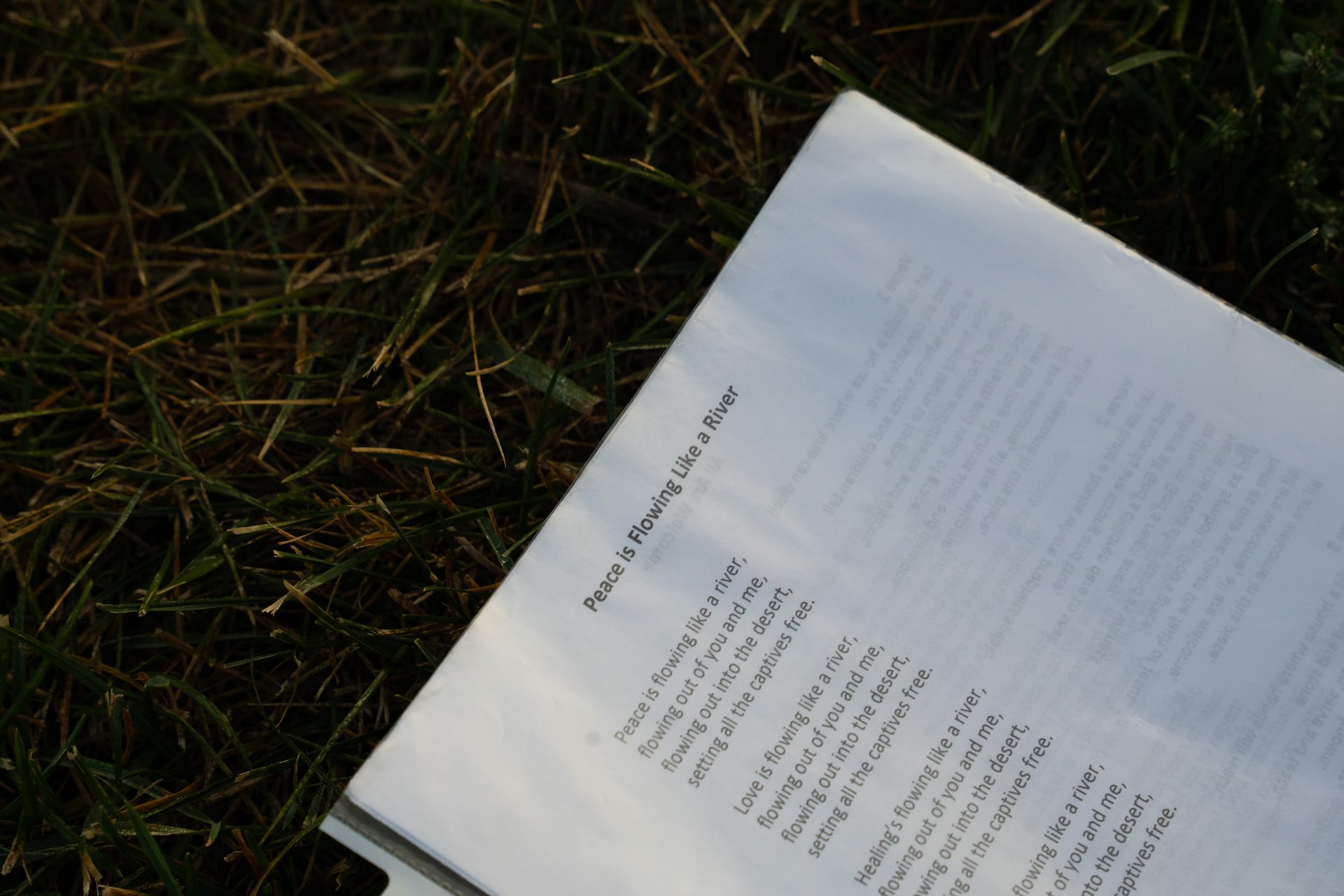

El grupo se reúne, con las cabezas inclinadas en señal de oración, en torno a un iPad utilizado para transmitir un servicio de la iglesia a través de Zoom. Murmuran oraciones en inglés y español. Al terminar el servicio, Berg y los demás se dan la mano y cantan una versión de "We Shall Overcome."

"Es una oración pacífica, pero está vinculada a los inmigrantes y refugiados y familias que vemos ser deportadas," dijo Berg. "Rezamos por ellos. Rezamos por compasión."

Noticias que ponen el poder en el punto de mira y a las comunidades en el centro.

Suscríbase a nuestro boletín gratuito y reciba actualizaciones dos veces por semana.

Durante casi 20 años, el grupo se ha reunido para rezar a las 7 de la mañana todos los viernes frente a la instalación de procesamiento del ICE en Broadview. Ha sido una protesta silenciosa y constante contra la deportación de sus vecinos inmigrantes. Pero recientemente, ese ambiente ha cambiado.

Durante el último mes, Beach Street se ha convertido en un punto álgido de la campaña de control migratorio del presidente Donald Trump en Illinois. Los manifestantes y los agentes del Departamento de Seguridad Nacional (DHS, por sus siglas en inglés) se han enfrentado. En varias ocasiones, los agentes han desplegado gases lacrimógenos y balas de pimienta contra manifestantes y periodistas. Más recientemente, la policía estatal ha empleado fuerza excesiva y ha arrestado a manifestantes, incluyendo líderes religiosos y clérigos.

A medida que han aumentado las tensiones, la rutina del grupo de oración, que se mantenía desde hace ya una década, ha cambiado — han perdido el acceso a los detenidos dentro del centro y ahora tienen que trasladar sus reuniones a lugares más alejados.

Los manifestantes dicen que se están movilizando para poner fin a las deportaciones y detenciones a medida que aumentan las políticas y la aplicación de las leyes de inmigración por parte de la administración de Trump.

Retrasar las operaciones de deportación "aunque solo sea por una hora... podría significar que el ICE secuestre a una o dos personas menos," dijo David Black, pastor de First Presbyterian Church of Chicago.

Las oraciones de Broadview han perdurado

La resistencia a las deportaciones en Broadview comenzó mucho antes de la represión de este año.

En diciembre de 2006, Berg se sintió abrumado por la sensación de impotencia ante el aumento anual de las deportaciones durante la administración del Presidente George W. Bush.

"Me estaba afectando mucho ver cómo destrozaban a esas familias," recuerda. "Dije, 'Soy más que un abogado. También soy católico,' y dije, 'Podemos rezar.'"

Ese mes, invitó a la gente a rezar un viernes por la mañana durante las deportaciones programadas del centro. Siguieron reuniéndose todas las semanas, incluso en los gélidos inviernos de Chicago.

La hermana JoAnne Persch y la hermana Pat Murphy, ambas apasionadas defensoras de los derechos de los inmigrantes y refugiados, se unieron a la congregación en enero del año siguiente. Abogaron por el acceso al centro para hablar y rezar con los detenidos.

Su defensa del acceso a los detenidos condujo a la aprobación de una ley en 2008 que garantizaba el acceso a atención espiritual para los inmigrantes detenidos, así como a la fundación de Illinois Community for Displaces Immigrants (ICDI, por sus siglas en inglés), que proporciona vivienda, necesidades esenciales y servicios para solicitantes de asilo.

Los retos pusieron a prueba al grupo durante los años siguientes, a través de nuevas administraciones presidenciales.

Durante la administración del presidente Barack Obama, entre tres y cuatro autobuses a la vez transportaban a los detenidos fuera del centro, recuerda Joaquín Martínez. Lleva unos 19 años participando en el grupo de oración y ahora también se ha unido al numeroso grupo de manifestantes en Broadview.

"Había una larga fila de gente que iba a despedirse de sus familiares," dice Martínez, inmigrante mexicano y fundador de una misión que dio origen al Santuario de Nuestra Señora de Guadalupe en Des Plaines, Ill. "Así que vimos derramar muchas lágrimas allí, y por eso seguimos luchando."

Desde finales de agosto, la pequeña congregación ha tenido que adaptar su planteamiento casi todas las semanas a medida que las tensiones fuera de las instalaciones alcanzaban un punto crítico.

En respuesta al conflicto, la alcaldesa de Broadview, Katrina Thompson, decretó un toque de queda de 9.00 a 17.00 horas para las protestas, limitando el activismo a "zonas de libertad de expresión" delimitadas con barreras de hormigón.

El grupo de oración, que solía reunirse justo frente a las puertas del centro con la esperanza de ser escuchado por quienes estaban dentro, ha perdido terreno semana tras semana. Ahora rezan a dos cuadras del edificio, en un intento de cumplir las normas locales.

Un punto de inflexión

El 29 de agosto, tres activistas se sentaron frente a camionetas del ICE para impedir que transportaran a detenidos al Gary Chicago International Airport para su deportación.

Desde aquella manifestación, el número de manifestantes ha crecido exponencialmente, reuniéndose casi a diario con el objetivo de cerrar la instalación. El conflicto también ha intensificado el activismo de los activistas religiosos, que consideran que la prohibición del acceso del clero al centro es una violación tanto espiritual como legal.

El 11 de octubre, una coalición de sacerdotes católicos, monjas y líderes laicos de la Coalition for Spiritual and Public Leadership (CSPL, por sus siglas en inglés) encabezó una procesión desde la iglesia Santa Eulalia de Maywood (Illinois) hasta el centro de detención de Broadview para ofrecer la comunión a los detenidos, pero los funcionarios del ICE les negaron el acceso.

"No hay nada estadounidense en esto," dijo el padre Daniel Hartnett tras negársele la entrada al centro. "Cualquier persona [que haya sido] detenida tiene derecho a recibir los sacramentos. Se les están negando derechos humanos básicos."

A pesar de la prohibición de los centros de detención de inmigrantes en Illinois, el Chicago Sun-Times informó que este año la instalación se ha convertido en un centro de detención de facto, donde algunas personas permanecen retenidas durante tres días o más sin camas.

La instalación de Broadview se ve directamente afectada por las nuevas políticas de inmigración de la administración Trump, argumenta Berg.

El mes pasado, la Junta de Apelaciones de Inmigración dictaminó que cualquier persona que entra en el país sin inspección no tiene derecho a fianza, lo que significa que deben permanecer en centros de detención mientras sus casos de inmigración avanzan en los tribunales.

"Nunca he visto nada tan cruel, tan despiadado," dijo Berg, que ha sido abogado de inmigración durante más de 40 años.

La decisión sobre la fianza se produce en un contexto de intensificación de la aplicación de las leyes de inmigración y de tácticas agresivas por parte de los agentes del ICE como parte de "Operación Midway Blitz," un plan para deportar en masa a los inmigrantes indocumentados con antecedentes penales en Illinois. Según el DHS, en el último mes se han realizado más de 1.500 arrestos en el área de Chicago. Borderless no ha podido verificar esta cifra.

Black, de First Presbyterian Church of Chicago, sigue protestando contra la instalación todos los viernes, y ha recibido gases lacrimógenos y un disparo de pimienta en la cabeza.

"Soy una de las muchas personas que se están informando sobre la instalación de Broadview y sobre el hecho de que han estado deteniendo allí a personas durante, a veces, varios días seguidos, llamándolo instalación de procesamiento," dijo Black.

Reconoce haber llegado "tarde" a los esfuerzos organizativos y haberse "subido a los hombros" de personas que llevan muchos años manifestándose frente a la instalación. Los dos grupos funcionan como "grupos separados que se apoyan mutuamente" en lugar de un movimiento unificado, dijo.

"Hay alguien rezando por ellos."

Ahora, Berg y otras personas que se unen a él en oración los viernes por la mañana se congregan más lejos de su lugar habitual después de que la policía local estableciera toques de queda y zonas de protesta en Broadview.

Mientras manifestantes y policías se enfrentan a pies de donde reza el grupo, Persch, que ahora se une a través de Zoom, dice, "Simplemente creo que es espantoso que en nuestro país hayamos recurrido a esto."

A pesar de las dificultades de Beach Street, Berg y otros que se unen a él en la oración no dan señales de detenerse.

"Levantamos nuestros rosarios, levantamos nuestra imagen de ellos sentados durante más de un día, para que vean y que sepan que hay alguien ahí rezando por ellos, alguien que se preocupará por ellos," dijo Berg.

Aydali Campa es miembro del equipo de Report for America y cubre temas de justicia medioambiental y comunidades inmigrantes para Borderless Magazine. Envíale un correo electrónico a [email protected].

Camilla Forte es becaria de CatchLight y miembro de Report for America que cubre las comunidades inmigrantes para Borderless Magazine. Envía un correo electrónico a Camilla a [email protected].