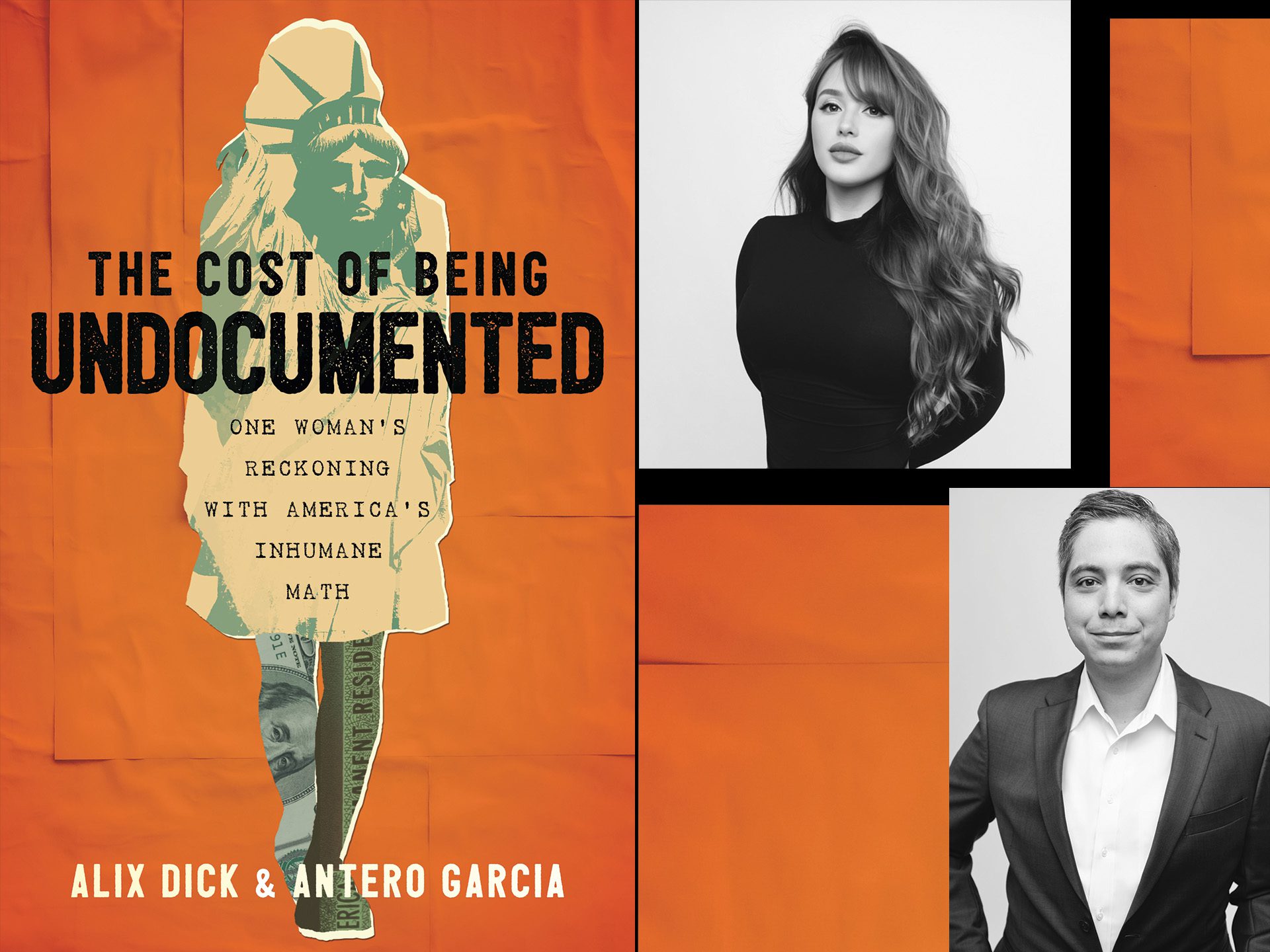

Fotos de Alix Dick y Antero Garcia por Caitlin Fisher Photography

Fotos de Alix Dick y Antero Garcia por Caitlin Fisher Photography En un extracto de su nuevo libro, Alix Dick y Antero García hacen recuento de los costes estructurales de la vida indocumentada.

Extraído de The Cost of Being Undocumented: One Woman's Reckoning with America's Inhumane Math, de Alix Dick y Antero García.

El coste del tiempo

Una vida sana debe tener un pasado que se pueda apreciar, un presente que ofrezca retos y alegrías, y un futuro al que aspirar. Sin embargo, debido a mis circunstancias, mi pasado no tiene nada para mí. No es más que una casa que perteneció a mi familia, despojada de las pertenencias de mi infancia y situada en una ciudad que ahora me es desconocida. Mi presente está lleno de gastos crecientes, todo para vivir en un país que no siempre me tolera. Y mi futuro es una serie de perspectivas sombrías y callejones sin salida.

Rara vez me preguntan por qué vivo en Estados Unidos. Me frustra que las circunstancias que traen a la comunidad indocumentada a este país se pasen por alto o se representen como estereotipos problemáticos. Es conveniente no tener que conocerme a mí y mi verdad. Así es más fácil mantenerme en una posición de explotación. Estados Unidos se beneficia de no reconocer por qué estoy aquí. Pero al compartir en este capítulo los costes de mi pasado, mi presente y mi incierto futuro, empezaré por la dolorosa historia que me trajo de allí a aquí, de entonces a ahora.

Noticias que ponen el poder en el punto de mira y a las comunidades en el centro.

Suscríbase a nuestro boletín gratuito y reciba actualizaciones dos veces por semana.

El pasado

Crecí en el seno de una familia muy acomodada en el estado mexicano de Sinaloa durante las décadas de 1990 y 2000. Si paseabas por las calles de mis ciudades natales de Culiacán y Navolato durante esos años, es posible que escucharas a los camiones de reparto tocando el jingle de la cadena de mi familia de tortillerías: "¡Tortillería Alix!" La cadena llevaba mi nombre, y las tortillerías eran una piedra angular de la riqueza de mi familia. Mi hermana y yo crecimos trabajando en varias de las tortillerías cercanas. Antes de convertirse en empresarios, mi padre ejerció de abogado mercantilista y mi madre fue directora y profesora de un colegio privado. Cuando yo era pequeña, ambos habían dejado esas carreras para centrarse en construir su imperio de comestibles.

Mi familia tenía varias casas y una colección de coches. Crecí entre niñeras y amas de llaves. Nos educaron con valores cristianos conservadores, apostólicos/pentecostales. Mis padres nos inculcaron a mí y a mis dos hermanos, junto con lecciones de humildad y respeto a todo el mundo, que el dinero era una ilusión que podía desaparecer. Por eso mis padres consideraron tan importante que mi hermana y yo trabajáramos en el negocio familiar desde muy pequeñas. Sinaloa había sido durante mucho tiempo un centro de cárteles de la droga. La escalada de violencia en mi ciudad y las amenazas de extorsión dirigidas a los negocios de nuestra familia hicieron que nunca diéramos por sentada nuestra comodidad.

Estas lecciones se compartían en silencio y deliberadamente. Mi padre era introvertido por naturaleza, aunque también una persona enérgica y exuberante. Sólo hablaba cuando tenía algo importante que decir. Hablaba y se movía despacio. Para mí era una presencia tranquila y firme, un ángel. Tenía tanta paz en el corazón que desbordaba por todos los rincones de nuestra casa. Mi infancia tiene como banda sonora a mi padre tocando himnos en el piano de nuestra familia. Nos quería a mí y a mis hermanos más que a nada.

En 2008, cuando yo estaba en la universidad, mi papá empezó a invertir en proyectos que implicaban colaborar con personas más allá de su red establecida. Un amigo de la familia le presentó a alguien interesado en asociarse para expandir nuestra cadena de tiendas por todo México, quizá incluso a nivel internacional. Mi padre obtuvo un importante préstamo de este inversor. Sin embargo, la oportunidad llegó en un momento desafortunado. La economía mundial empeoró y nuestras vidas empezaron a ir cuesta abajo. Las ventas bajaron y la gente de la ciudad se vio obligada a arreglárselas con menos dinero, comprando menos comestibles o tortillas de más. Mi padre empezó a trabajar horas interminables, pues había que despedir a empleados de toda la vida.

Parecía que todo el mundo en mi país estaba perdiendo dinero. Las empresas cerraban. Mucha gente a nuestro alrededor perdía sus casas y sus coches. Las particularidades de la vida en Sinaloa hacían aún más adversa esta situación. En aquella época, el 90% de la cocaína de Estados Unidos se introducía de contrabando desde México, gran parte de la cual estaba controlada por los cárteles de Sinaloa. La escalada de enfrentamientos entre cárteles y con los gobiernos mexicano y estadounidense hizo que la vida en Sinaloa fuera aún más peligrosa. Los tiroteos en las calles, los robos a plena luz del día y los secuestros eran sucesos cotidianos. Las familias que disponían de medios huyeron de la zona. Mi familia también tenía planes de mudarse y abrir tiendas en Cabo. También sabíamos que las deudas de nuestra familia nos seguirían a otro estado. Retrasamos nuestra partida, con la esperanza de hacer primero una mella sustancial en el dinero que debíamos. Sin embargo, a pesar de sus esfuerzos, mi padre se vio incapaz de hacer frente a los pagos a su nuevo socio comercial.

Uno de los mayores temores de mis padres era que mi hermana, mi hermano o yo nos viéramos envueltos en la vida de los cárteles. Debido a esos temores, quizá nos protegieron demasiado. No nos permitían, por ejemplo, escuchar el popular narcocorridos que glorificaba los horripilantes crímenes del cártel en las calles de Culiacán.

Los corridos son un género de baladas narrativas en México, y los narcocorridos se centran en la violencia de los cárteles. Cati de los Ríos, profesora asociada de la Universidad de Berkeley, me explicó a través de una llamada de Zoom: "Los narcocorridos se dispararon a finales de los 90 y en la década de 2000. Alrededor de 2010, el gobierno [mexicano] empezó a prohibirlos en la radio. A los niños básicamente no se les permitía escucharlos. Y esa es también la razón, en cierto modo, por la que muchos corredores en México venían a Los Ángeles y encontraban refugio en ciertos sellos discográficos porque pensaban: 'Vale, es menos probable que nos demanden por difamación o que nos maten por este lado si firmamos con [sellos discográficos en EE.UU.]'".

Al explicar sus años de trabajo escuchando, entrevistando y observando a los jóvenes mexicanos que escriben y escuchan corridos en California, de los Ríos tiene cuidado de dejar claro que los narcocorridos violentos son sólo una parte de los corridos que circulan más ampliamente: "Muchos de los chicos, sí, escuchaban narcocorridos. Pero tampoco era necesariamente un modelo de cómo vivir la vida. Era, para ellos, una especie de lectura y aprendizaje sobre los horrores del capitalismo y la guerra contra las drogas".

Esta glorificada guerra contra las drogas era el centro de atención de mi familia. El estrés de la nueva realidad financiera provocada por esa guerra, además de la recesión mundial, pesaba mucho sobre mi padre. La casa se volvió más silenciosa mientras él se encerraba en sí mismo, tratando de encontrar una manera de sacarnos de la creciente deuda. En pocos meses, su pelo encaneció y su figura, antes ágil, adelgazó de forma alarmante. En 2009, un anciano había sustituido a la persona que yo conocía como mi padre.

Fue entonces cuando empezó a vender nuestros coches, nuestros negocios y nuestras casas. Las cosas empezaron a ponerse tensas en casa, pero yo era demasiado joven para comprender que mi padre estaba inmerso en una pesadilla viviente.

Dos años después, a finales de 2010, cuando yo tenía diecinueve años, mi padre nos reunió para una conversación muy dura. Éramos los cinco: mi padre, mi madre, mi hermana mayor, Cindy, mi hermano de ocho años, AC, y yo. En la mesa donde habíamos compartido las cenas de Navidad y reído como una familia, mi padre se encorvó en un asiento diagonal al mío, no en su habitual posición en la cabecera. Exhaló lentamente, controlando la voz. Nos contó que había descubierto que su nuevo socio había estado blanqueando dinero para uno de los principales cárteles de la droga de Sinaloa. Esto significaba que el socio era un hombre increíblemente peligroso. Los nuevos guardaespaldas que mi padre había contratado de repente para la seguridad de nuestra casa ahora tenían sentido. Mi familia ya había contratado guardaespaldas antes, cuando yo era más joven y la violencia relacionada con los cárteles se había agravado especialmente, pero la aparición de esta seguridad adicional había sido una sorpresa. En aquel momento, no sabíamos que la deuda que teníamos se convertiría en el punto de ruptura de nuestra familia. Que nos separaría.

A medida que mi padre hablaba, se hizo evidente que la pesadez que llevaba encima le estaba matando. Nos contuvimos mutuamente, sin querer llorar, mientras escuchábamos a mi agotado padre. Me derrumbé en silencio, secándome las lágrimas para que mi padre me viera fuerte. Me puse de pie y me paseé ansiosamente por el comedor, demasiado agitada para permanecer sentada, mientras mi padre decía: "¿Sabéis qué? Vamos a tener que vender las otras casas. Vamos a quedarnos con esta casa porque este es nuestro hogar. Vamos a vender todos los coches. A fin de cuentas, no me importa si perdemos cosas materiales. Sólo tengo miedo de que nuestras vidas corran peligro".

El peligro resultó ser mayor de lo que mis hermanos y yo podíamos imaginar en aquel momento. Mis padres nos ocultaban el hecho de que miembros del cártel habían estado en contacto regular con mi padre, y que él había vendido algunos de nuestros coches y nuestras casas para mantenerlos alejados de nosotros. Aunque Cindy, AC y yo podíamos ver cómo se agotaba nuestro patrimonio, no podíamos ver hasta qué punto mi padre entregaba desesperadamente nuestras pertenencias en un intento de protegernos.

Al final de la conversación, mi padre dijo algo que se me ha quedado grabado en el corazón: "Lo estamos perdiendo todo. Pero mira, somos nosotros cinco. No vamos a centrarnos en lo que ya no tenemos, que es dinero. Vamos a centrarnos en lo que nos queda: nosotros cinco."

Lo dijo dos veces más. Vamos a centrarnos en lo que nos queda: nosotros cinco. Vamos a centrarnos en lo que nos queda: nosotros cinco..

Pienso en esa frase todos los días de mi vida.

Cuando oí eso, me di cuenta de que probablemente íbamos a acabar sin casa. Pero oír a mi padre decir "nosotros cinco" me reconfortó. Me recordó que las dificultades ocurren en la vida. Podríamos perder todos los lujos de la riqueza, pero no pasaba nada. Nos seguiríamos teniendo los unos a los otros. Aquella noche dormí sabiendo que tenía a mi familia.

El día que lo perdí todo

Soy dieciocho meses menor que mi hermana, pero a las dos siempre nos trataron como "hermanas mayores". Si eres una hermana mayor en México, eres como una madre. Prácticamente tuvimos que criar a nuestro hermano pequeño como un equipo, porque esa era la expectativa cultural. Como resultado, desarrollé muchas de las habilidades en las que confío hoy en día. Puede que mis padres trabajaran duro, pero nosotros también.

Una de mis tareas en casa era cocinar. Me encantaba cocinar porque mi padre lo apreciaba mucho. Siempre estaba muy agradecido cuando cocinaba un plato especial solo para él. Una tarde de diciembre de 2010, decidí prepararle camarones en crema mientras estaba en el trabajo. Le encantaba el marisco.

Había hecho un buen trabajo preparando ese plato y estaba deseando que volviera a casa.

Pero nunca llegó a casa a comer esa comida. Justo antes de las seis, uno de sus empleados empezó a llamar a gritos a mi hermana: "¡Cindy! ¡Cindy! Cindy!"

Cindy y yo fuimos a la ventanilla. El empleado nos dijo que nuestro padre iba al hospital en ambulancia. Se había desmayado.

Mi hermana y yo cogimos las llaves, fuimos al hospital y esperamos horas para verle, mientras mi madre permanecía junto a su cama. Finalmente, salió y nos dijo algo que no entendí del todo: "Vuestro padre se desmayó y se despertó sin memoria". Acababa de ver a mi padre aquella mañana. ¿Cómo podía no tener memoria?

Durante tres días, los médicos intentaron averiguar qué le pasaba. Al tercer día, un médico nos dijo que mi padre tenía cinco tumores cancerosos en el cerebro. Por ellos no recordaba nada.

El médico añadió entonces que los efectos de los tumores en su cerebro y su percepción eran la razón por la que los médicos se habían visto obligados a atar a mi padre a la cama. Mi madre nos había ocultado esa información. Nos había estado protegiendo de la realidad de que mi padre había estado intentando escapar del hospital, gritando que tenía que irse a casa.

Mi padre permaneció en esa cama durante treinta y dos días. El 2 de enero de 2011, recuperó la memoria durante tres minutos. Nos dijo: "Me voy a ir con Dios muy pronto". Estaba llorando. Y dijo que quizá las cosas no fueran más fáciles ahora, pero que teníamos que confiar en Dios de que en algún momento las cosas mejorarían. Nos dijo a Cindy y a mí: "Todo el tiempo os he estado diciendo cómo ser fuertes, sabias y valientes. Lo más importante que tenéis que hacer es proteger a vuestro hermano y protegeros entre vosotras. Vuestras vidas están en peligro, así que tenéis que tener cuidado con cada movimiento que hagáis. Tenéis que manteneros a salvo".

Aquella noche dormí en el frío suelo del hospital, junto a su cama. Aunque era incómodo, estaba muy agradecida por acostarme junto a mi padre por última vez. Cuando oí su respiración agitada a las seis de la mañana, me levanté. Le costaba respirar. Le cogí la mano porque pensé que podía estar teniendo una pesadilla.

Lo que sucedió después fue una de las mayores bendiciones de mi vida. Vi morir a mi padre. Vi cómo daba su último suspiro. Aunque fue una pesadilla, fue un honor presenciarlo.

Era inútil intentar recomponerme. Salí al pasillo y todo el mundo estaba allí: mis abuelos, mi madre, mi hermana y el médico. En cuanto me vieron la cara, supieron que se había ido.

Les seguí hasta su habitación. Ahora desearía no haberlo hecho, porque me arrepiento de lo que vi. Los médicos intentaron reanimarle poniéndole todo tipo de cosas en el pecho, pero nada sirvió de nada. Sabía que nada le iba a devolver la vida.

Yo era la persona que tenía que decir al resto de nuestra familia y amigos que mi padre había muerto. Y entonces llegó el momento para el que mi padre me había preparado: decírselo a mi hermano. Cuando le abracé y le di la noticia, se quedó completamente destrozado. Me dijo: "Oye, vamos a estar bien. Vamos a estar bien". Me agarró la cara con una confianza desconocida. Creo que su firme agarre era Dios recordándonos que, como había dicho mi padre, las cosas podrían ir mal, pero estaríamos bien. En aquel momento, mi hermana y yo estábamos en la universidad. Ahora no podríamos terminarla. Aún debíamos mucho dinero y nuestras vidas corrían peligro. La muerte de mi padre no borró nuestro saldo y ya no teníamos dinero para pagar seguridad o sobornos. Una ley tácita de Sinaloa es que si no puedes pagar a los cárteles con dinero, al final pagarás con tu vida.

Buscar ayuda de amigos o familiares en otras ciudades mexicanas sería ponerlos en peligro. Como no teníamos dinero ni recursos para escondernos en ningún otro estado, tuvimos que salir del país.

Los forasteros no entienden que en estados mexicanos como Sinaloa, si alguien quiere matarte, puede contratar a un sicario por $100 y esa persona te matará. Encontrar un sicario es tan fácil como entrar a Amazon y que te entreguen un paquete. Amo a México con todo mi corazón, pero no puedo negar lo fácil que es cometer crímenes allí. En Estados Unidos, en cambio, se comprueban los antecedentes de los mexicanos que desean entrar en el país, lo que hace impracticable cruzar la frontera para quienes tienen antecedentes penales. La vigilancia a la que me sometí para obtener un visado de turista a EE.UU. significaba que los delincuentes violentos no seguirían a mi familia hasta aquí.

Yo tenía una vida en México. Tenía amigos, familia, escuela y una iglesia. Tenía un restaurante favorito. Tenía un lugar en la playa donde el sol besaba mi nariz todo el año. Todo eso me lo arrebataron porque necesitaba seguir vivo. Si me hubiera quedado en México, puedo asegurarles que estaría muerto.

Teníamos un amigo de la familia en Georgia que se ofreció a escondernos de la gente que quería matarnos. AC y yo nos iríamos a vivir con ellos. En ese momento, yo tenía veinte años y él nueve. Mi madre y mi hermana iban a quedarse en México para intentar pagar nuestras deudas vendiendo lo que quedaba de nuestras casas, coches y pertenencias. Se mudaban de ciudad en ciudad, sin quedarse mucho tiempo en el mismo sitio.

Han pasado los años, cada uno con nuevas sorpresas. Mi madre sigue intentando asimilar nuestras pérdidas colectivas. En cuanto a mí, nunca tuve la oportunidad de llorar a mi padre. Estaba en Estados Unidos intentando ganarme la vida y aprendiendo a ser madre de mi hermano pequeño.

Antes y después

Nuestras vidas se dividen en una serie de antes y después, momentos que alteran irrevocablemente el terreno de adónde iremos y en quién nos convertiremos.

Antes de que muriera mi padre. Y después.

Antes de que la pérdida y los cárteles de la droga me enviaran a través de fronteras geográficas y husos horarios. Y después.

Antes de que EE.UU. me viera como "ilegal". Y después.

También hay acontecimientos que hendieron el mundo mucho antes de que yo naciera. Antes de que las fronteras hicieran ilícitas a las personas. Y después. Este mundo escindido aún puede unirse en algún momento futuro, si se suprimen las fronteras.

Mientras me enfrento sin querer al coste del futuro incierto que me ha tocado en suerte, pienso en los millones de personas indocumentadas que hay en este país y me pregunto cómo afrontan esta misma ansiedad. Exhalamos colectivamente una nube negra cada día, tratando de mantener este estrés dentro de nosotros. Últimamente, me pregunto cómo será el futuro si sigo quedándome en Estados Unidos. No sé cuánto tiempo más podré vivir así.

Estar en Estados Unidos es una batalla contra el tiempo. Dejé todo de mí en el pasado y tuve que reconstruirme a través de la terapia, la creación de redes y pasos cuidadosos para evitar la deportación. A pesar de lo en desacuerdo que estoy con este país y de lo mucho que me deshumaniza, conservo el amor por la posibilidad de lo que puede llegar a ser Estados Unidos. Aunque no me sienta segura, sé que estoy viva porque vine aquí. Soy un residente que ama este país, y sin embargo aquí sólo se me da cobijo, ni siquiera soy tolerado por la mayoría de la gente. Quiero que este lugar me acoja con seguridad.

Hace poco, me puse al día con algunos de mis amigos de Los Ángeles en una llamada de Zoom. Cuando empezó la pandemia, decidieron alquilar una casa en la playa para poder hacer surf mientras se aislaban. Vivieron allí gran parte de lo peor de la pandemia, surfeando todos los días.

Ahora están todos de vuelta en casa. Tienen trabajos bien pagados, un futuro seguro. Así que, mientras estábamos en Zoom, empezaron a hablar de que quizá, cuando se hicieran mayores y estuvieran listos para jubilarse, podrían comprar una casa juntos en Hawai o en la playa aquí en California. Entonces podrían "ser libres". Era el tipo de ensoñación lúdica respaldada por posibilidades financieras y legales reales. Podría hacerse realidad algún día si ellos quisieran. Para ellos.

Amo a estos amigos. Pero no tienen ni idea de cómo es mi vida. Claro que saben que soy indocumentada, pero en nuestras conversaciones siempre queda claro que nadie entiende del todo lo que eso significa para mí. Siempre dan por sentado que se trata de una pequeña laguna legal que con el tiempo será fácil de solucionar. No me considero una persona celosa, pero la verdad es que estoy celosa de la capacidad de mis amigos para visualizarse a sí mismos en el futuro.

Me aterra no ser capaz siquiera de soñar con un futuro para mí cuando sea mayor. Es una de las razones por las que no dejo de preguntarme: "¿Merece la pena quedarse en Estados Unidos?". Pero ahora mismo no tengo otras opciones seguras para vivir. Estoy atrapada en el doble vínculo de la vida indocumentada: un pasado peligroso me obliga a un futuro incierto. No sé qué me depararán las próximas décadas. Pero tampoco sé dónde estaré dentro de un año, o dentro de seis meses. El futuro es dentro de cinco minutos, y en ese tiempo, mi mundo podría derrumbarse de repente, otra vez.

Extraído de The Cost of Being Undocumented: One Woman's Reckoning with America's Inhumane Math por Alix Dick y Antero García. Copyright 2025. Extraído con permiso de Beacon Press.