Caroline Gutman/Inside Climate News

Caroline Gutman/Inside Climate NewsHoboken (Nueva Jersey), una ciudad propensa a las inundaciones, ha abierto una zona de juegos para sus residentes más jóvenes que también sirve para almacenar las aguas pluviales.

Este reportaje forma parte de un proyecto de información en colaboración dirigido por la Instituto de Noticias sobre las Organizaciones sin Ánimo de Lucro e incluye Revista Borderless, Cicero Independiente y Noticias sobre el clima. Contó con el apoyo del Fundación Field e INN.

HOBOKEN (Nueva Jersey)-Para ser una ciudad casi tan pequeña que cabe en el Central Park de Manhattan, a pocos kilómetros de distancia, Hoboken (Nueva Jersey) ha visto pasar mucha historia dentro de sus estrechas fronteras.

Fue el emplazamiento de la primer partido de béisbol organizado en 1846, hogar de uno de las primeras cervecerías del país en el siglo XVII y el lugar donde se vendieron por primera vez las galletas Oreo en 1912. Y, como le dirá cualquier hobokenita, la ciudad de la milla cuadrada, como se la llama, también es conocida por algo más.

"Todo se inunda aquí arriba", dijo Maren Schmitt, de 38 años, con una risita nerviosa un reciente martes por la tarde, mientras observaba a sus dos hijos trepar en un parque infantil de la ciudad.

Noticias que ponen el poder en el punto de mira y a las comunidades en el centro.

Suscríbase a nuestro boletín gratuito y reciba actualizaciones dos veces por semana.

De hecho, casi cuatro quintas partes de la superficie de Hoboken, situada en la ribera occidental del río Hudson, corresponden a la zona de la ciudad. en una llanura inundable. Y su intensa susceptibilidad a las inundaciones probablemente nunca ha sido más evidente que durante la supertormenta Sandy en 2012, cuando 500 millones de galones de marea de tempestad inundaron la ciudad.

Ahora, una docena de años después de la tormenta, las autoridades de Hoboken han puesto en marcha una serie de medidas destinadas a mitigar los efectos destructivos de las tormentas provocadas por el cambio climático, incluida una innovación que la ciudad espera que se conozca como otra primicia de Hoboken.

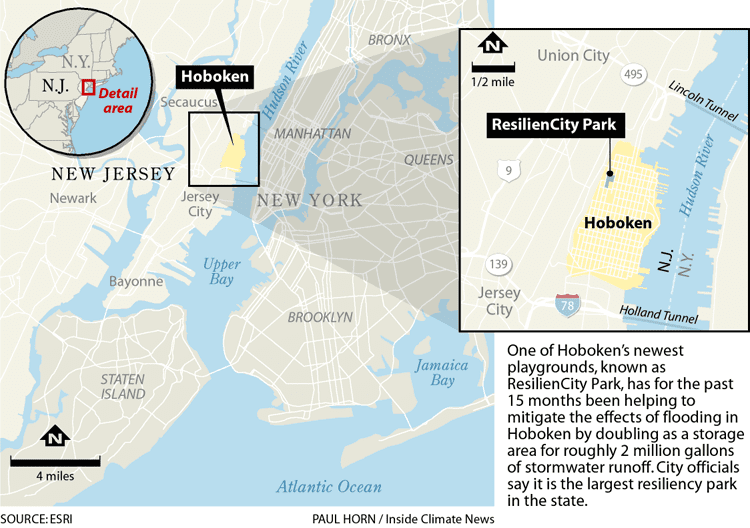

Situado en la esquina de las calles 12 y Madison, uno de los parques infantiles más nuevos de Hoboken, conocido como ResilienCity Park, lleva 15 meses ayudando a mitigar los efectos de las inundaciones en Hoboken al servir de zona de almacenamiento de unos 2 millones de galones de aguas pluviales de escorrentía. Las autoridades municipales afirman que es el mayor parque de resiliencia del estado.

El parque, que ocupa una superficie de dos hectáreas a apenas kilómetro y medio del túnel Lincoln de Manhattan, cuenta con columpios, toboganes, una cancha de baloncesto y un campo de atletismo, además de un depósito subterráneo capaz de retener cientos de miles de litros de aguas pluviales que, según las autoridades municipales, de otro modo se habrían vertido a las calles o a los sótanos de las viviendas y comercios de Hoboken.

La construcción de parques infantiles resistentes al cambio climático forma parte de un movimiento creciente tanto entre los municipios como entre los grupos de defensa del medio ambiente. Aunque no se dispone de cifras exactas sobre el número de áreas de juego en todo el país que se han reconfigurado como espacios respetuosos con el clima, el Trust for Public Landun grupo conservacionista sin ánimo de lucro, calcula que ha ayudado a financiar la construcción de más de 300 espacios de juego de este tipo en comunidades de todo el paíscomo Filadelfia, Nueva York y Los Ángeles.

En Chicago, los parques resistentes son parte integrante de la proyectos de infraestructura previstos en la ciudad. En el West Side de Chicago, por ejemplo, El Conservatorio Garfield Juega y crece en la naturaleza ha sido diseñado para utilizar árboles y jardines de lluvia que ayuden a gestionar la escorrentía de las aguas pluviales. Según las autoridades municipales, hay al menos otros 16 espacios de recreo que suman un total de 2.000 acres y que cuentan con plantas de raíces profundas que ayudan a ralentizar la escorrentía de las aguas pluviales al permitir que penetren en el suelo.

Algunos espacios, como los de Hoboken, utilizan un depósito subterráneo, césped artificial poroso e imbornales o aberturas en una cancha de baloncesto para almacenar el exceso de aguas pluviales. Otros aumentan la resiliencia con árboles recién plantados que pueden absorber el dióxido de carbono y los contaminantes atmosféricos; una vez que maduran, esos árboles también proporcionan una cubierta de sombra que puede reducir el efecto de isla de calor de las zonas urbanas, un problema intensificado por los tradicionales parques infantiles de asfalto negro habituales hace generaciones.

Los expertos en planificación medioambiental afirman que los nuevos espacios reflejan el interés de muchas ciudades y pueblos por construir infraestructuras multifuncionales teniendo en cuenta el cambio climático.

"Este parque infantil es uno de los muchos buenos ejemplos en los que realmente pensamos: Vale, es un lugar para que jueguen los niños, pero también es un lugar para almacenar las aguas pluviales". Daniella Hirschfeldprofesor adjunto de la Universidad Estatal de Utah que estudia la planificación medioambiental. "También puede ser un lugar para tratar las aguas pluviales. Y puede convertirse en un centro de refrigeración durante episodios de calor extremo. Puede ser una oportunidad de aprendizaje, una forma de que la gente se involucre y adquiera conocimientos sobre estos temas. Así que hay que pensar en la multifuncionalidad de las infraestructuras y los terrenos".

Aunque este tipo de versatilidad no es nuevo en la planificación urbana, a la hora de afrontar el cambio climático puede adoptar un cariz distinto según la geografía, explica Hirschfeld. Según ella, todo depende de las distintas formas en que el cambio climático y sus efectos -temperaturas extremas, incendios, inundaciones y mareas de tempestad- se manifiesten en los distintos lugares.

"Cada geografía va a tener factores de estrés ligeramente diferentes", dijo Hirschfeld. "Hoboken es un lugar que solía ser una isla. Y la cantidad de agua que necesita almacenar es muy diferente de la que yo necesito aquí, en Utah. Pero en última instancia, ya sabes, los lugares pueden funcionar tanto como un refugio seguro para las aguas pluviales como, hipotéticamente, incluso pueden ser un refugio seguro para el fuego, que es otra amenaza a la que nos enfrentamos."

Caleb Strattonjefe de resiliencia de Hoboken, recuerda cómo las autoridades municipales le pidieron que dirigiera los esfuerzos de reconstrucción y recuperación tras el huracán Sandy, un componente clave del cual implicaba abordar el antiguo problema de la ciudad con las inundaciones, que se ha visto exacerbado por el calentamiento global.

El parque, uno de los cuatro sitios de resiliencia previstos en la ciudad, se pagó principalmente con subvenciones para la reposición de infraestructuras, incluidos unos $10 millones de la Agencia Federal de Gestión de Emergencias. Stratton dijo que un elemento clave del diseño del parque es su enfoque múltiple para mitigar las inundaciones.

"Es un parque, una estación de bombeo de aguas pluviales, todo", dijo Stratton durante una entrevista en el parque mientras un grupo de campistas de verano chillaba en un parque infantil cercano. "Se trata de todas las estrategias mezcladas en una, y de ser agresivos tanto para mejorar la comunidad como para hacer frente al riesgo de inundaciones".

Además del tanque subterráneo de detención de aguas pluviales, con capacidad para un millón de galones de agua, Stratton dijo que la infraestructura sobre el suelo, incluidos los jardines de lluvia, puede contener un millón más. Una bomba subterránea también puede devolver el agua al Hudson.

"Lo que estamos haciendo es crear lugares para que el agua vaya a parar, de modo que podamos gestionarla y mantenerla fuera de las calles, alejada de los edificios de la gente, y prepararnos para un futuro incierto, que en cierto modo estamos experimentando en tiempo real".

Stratton señaló que el parque infantil está construido en un terreno que tenía sirvió como planta química desde el siglo XIX hasta hace unos 20 años. El emplazamiento fue rehabilitado y sellado por la empresa química alemana BASF, que lo vendió a la ciudad de Hoboken en 2016.

Con esa historia en mente, dijo Stratton, el concepto de diseño de gran parte del parque era "restaurar la ecología natural".

"Si no pasan coches, se oye el zumbido de las abejas y el canto de los grillos", explica Stratton. "Esto es lo que había antes de este parque. Esto es lo que había antes del solar de BASF, que era una zona industrial abandonada".

Stratton dijo que la estrategia de la ciudad es "no sólo reconstruir, sino reconstruir mejor, reconstruir de forma más integral".

"Como si pudiéramos construir más estaciones de bombeo", dijo. "Pero se convierte en una infraestructura aislada que no cuenta una historia sobre cómo la comunidad se está adaptando al cambio climático".

Martin Karaba Bäckström, investigador de la Universidad de Lund (Suecia), afirma que los parques infantiles son importantes para la salud de los niños. Es autor de un estudio sobre parques infantiles al aire libre y descubrieron que preparar estos espacios para las catástrofes climáticas no sólo creaba resiliencia para la comunidad, sino que podía generar "muchas espirales de salud positivas para los niños en su vida cotidiana".

Karaba Bäckström, terapeuta ocupacional y candidata al doctorado, afirma que cuando los niños interactúan con distintos ecosistemas y diferentes elementos naturales en un espacio resiliente al clima, se favorece su desarrollo mental y físico.

Los parques infantiles tradicionales minimizan el riesgo y tienen materiales duros y poco naturales. Pero en un parque resiliente al clima, dijo, hay posibilidades de que los niños encuentren un insecto interesante porque el parque tiene más madera muerta o suelos más penetrables para los insectos.

Dijo que, en teoría, ese descubrimiento despertará un mayor grado de curiosidad entre los niños y les llevará a aprender sobre la naturaleza.

"Cuanto más se expone uno a la naturaleza, más se crea el amor y el comportamiento de estar al aire libre y en la naturaleza", dijo Karaba Bäckström. "Si aumentamos la cantidad de entornos de juego basados en la naturaleza que atienden tanto a más servicios ecosistémicos como a una mayor resistencia al cambio climático... más niños querrán ir a la naturaleza".

También dijo que podría ayudar a preparar a los niños para la incertidumbre que se avecina, inspirando un comportamiento más adaptado al clima.

Desde su apertura en junio de 2023, el parque de Hoboken se ha convertido en un centro neurálgico para los padres de la zona, como Maren Schmitt, que lo visitaba por primera vez con sus hijos Theo, de 5 años, y Benno, de 3, y ya estaba deseando repetir.

Schmitt, que gestiona el Panadería Otok de la ciudad, dijo que como el diseño del parque se basaba en reducir los daños del cambio climático, había muchos momentos de enseñanza en medio del recreo de sus hijos.

"Es bueno que los adultos también lo conozcan porque, sinceramente, yo no sabía nada de esto. "Es bueno que los adultos también lo conozcan porque, sinceramente, yo no sabía nada de esto. Creo que Hoboken lo necesita porque, obviamente, todos luchamos contra el cambio climático -y Hoboken se ve especialmente afectada por él en lo que respecta a las inundaciones, por ejemplo- y, por tanto, cuanto más podamos hacer para preservar nuestra hermosa ciudad, mejor".

Y para los residentes de Hoboken, una parte clave de esa preservación pasa por crear más espacios de juego para los jóvenes. Además de ser uno de los municipios más pequeños de Nueva Jersey por superficie, es también el más pequeño del país. cuarta comunidad más densamente poblada con más de 57.000 personas hacinadas en sus 1,25 millas cuadradas.

"Se necesitan más parques como éste, para que los niños puedan salir al aire libre", dijo Tyrik Davis, de 26 años, residente en la cercana Fairview (Nueva Jersey), que visitaba el parque con sus hijos, Naylani, de 6 años, y Tyrik Jr., de 3. "Especialmente esta generación. Ya no hay niños en los parques. Están todos dentro con sus teléfonos".

Además de esas preocupaciones prácticas, otros padres dijeron que esperaban que, a medida que los niños aprendieran más sobre las fuerzas del cambio climático que impulsaron la creación del parque, podrían inspirarse para ser más conscientes del medio ambiente.

"Ver que el aspecto medioambiental se incorpora a la vida cotidiana es estupendo", declaró Nick Sims, de 49 años, que jugaba en el parque con su hijo Henry, de 5 años. "Si se puede empezar a pensar en ello y convertirlo en la norma, es estupendo. Igual que reciclar es normal".

Para padres como Schmitt, esa sensación de normalización no puede llegar lo bastante pronto.

"Espero que otras ciudades de Estados Unidos se inspiren en esto y sigan haciéndolo", afirmó. "Necesitamos más de esto".

Esta historia fue producida por Dentro de Climate News.