Max Herman/Borderless Magazine

Max Herman/Borderless MagazineAunque el Presidente Biden amplió el estatus de protección temporal para los venezolanos, las barreras lingüísticas del TPS, los largos tiempos de espera y las costosas tasas de solicitud dificultan que muchos inmigrantes puedan solicitarlo.

Unas frondosas plantas verdes bordean la ventana de una pequeña casa de ladrillo en McKinley Park. En el interior de la casa poco iluminada, un tímido gato gris y blanco se ha convertido en el nuevo amigo de Moisés Gacias, ayudándole a combatir la soledad de estar en un nuevo país. Por la noche, el emigrante venezolano cierra los ojos ante la visión de la figura gris y cada mañana se despierta junto al pequeño felino.

Noticias que ponen el poder en el punto de mira y a las comunidades en el centro.

Suscríbase a nuestro boletín gratuito y reciba actualizaciones dos veces por semana.

Gacias hizo el viaje de 69 días para venir a Chicago y poder enviar dinero a su mujer, sus tres hijos y su madre, que se está recuperando de una operación y recibe tratamiento contra el cáncer.

Pero en los seis meses que lleva aquí, Gacias no ha conseguido un permiso de trabajo, y sus esperanzas de mantener a su familia no se han cumplido.

Como uno de los más de 24.000 inmigrantes que han llegado a Chicago desde agosto de 2022, las opciones de Gacias para trabajar son limitadas. Podría intentar encontrar trabajo ilegal. Pero incluso este trabajo, que a menudo está por debajo del salario mínimo y con condiciones laborales peligrosas, es difícil de encontrar.

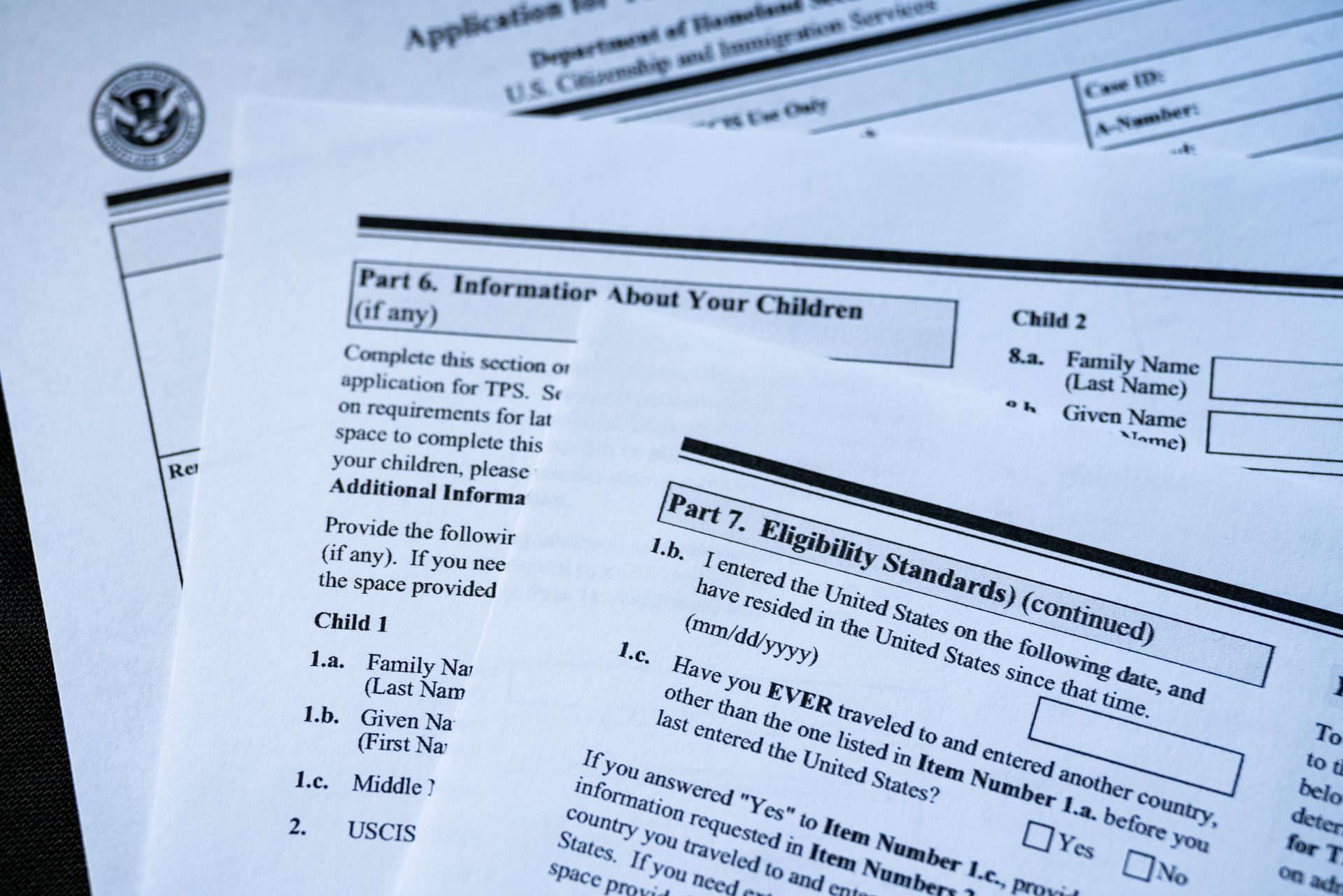

Otra vía para trabajar es solicitar el Estatus de Protección Temporal (TPS)que le protege de la deportación y le permite obtener un permiso de trabajo. Sin embargo, las barreras lingüísticas y tecnológicas, las elevadas tasas de solicitud, los largos tiempos de espera y las complicadas preguntas de la solicitud crean un proceso inaccesible -y casi imposible de completar- para inmigrantes recién llegados como Gacias.

"A veces te dicen que cuando entres en Estados Unidos habrá muchas oportunidades de trabajar y de tener cosas", dijo Gacias. "Pero no puedo trabajar si no tengo permiso, y dondequiera que voy me lo piden".

En septiembre, la administración Biden ampliado el Estatus de Protección Temporal (TPS) designación para los venezolanos que llegaron a EE.UU. antes del 31 de julio, abriendo la puerta a que miles de inmigrantes venezolanos en Chicago soliciten protección contra la deportación y permisos de trabajo.

Aunque el TPS concede protección temporal frente a la deportación, el programa no ofrece a los solicitantes una vía hacia la ciudadanía.

Quienes solicitan el TPS se enfrentan a retrasos en el proceso de inmigración, lo que significa que pueden pasar meses antes de que puedan trabajar legalmente en Estados Unidos. Y eso solo si logran superar el desalentador y complejo proceso de solicitud.

Docenas de preguntas, huellas dactilares y $545

Antes de poder presentar su solicitud, Gacias se esforzó por rellenarla. La solicitud, totalmente en inglés, requiere que el solicitante suba una foto suya. Sin embargo, la foto debe subirse en un formato de archivo concreto con unas dimensiones muy específicas.

Para rellenar la solicitud, Gacias recurrió a la ayuda de una voluntaria local que conocía, pero incluso así, la voluntaria, que habla inglés y español con fluidez, no pudo ayudar a Gacias por sí sola. Hacer y subir la foto les llevó casi tres horas. El portal en línea no les permitió seguir trabajando en la solicitud hasta que pudieron subir la foto.

"Tienes que tener un portátil, una impresora, de todo", dijo Gacias. "Calificar para el TPS no debería ser un privilegio para una sola persona. El TPS debería ser para todos por igual".

La solicitud TPS contiene docenas de preguntas que span 13 páginasen las que se pregunta al solicitante por sus antecedentes penales, su situación familiar, su situación en materia de inmigración, etc.

La solicitud requiere una prueba de residencia y de nacionalidad venezolana. Para Gacias, eso significaba pedir a su familia en Venezuela que obtuviera documentos oficiales de las autoridades locales, como su cédula de identidad, antes de subir una copia digital a un portal de solicitudes en línea.

La tasa de solicitud del TPS y del permiso de trabajo es de $545 para las personas de entre 14 y 65 años. Las tasas incluyen una tasa de $85 por "Servicios biométricos", que cubre el coste de la recogida de información biométrica, como las huellas dactilares.

Las elevadas tasas de solicitud han supuesto un obstáculo para muchos de los inmigrantes venezolanos que intentan solicitar el TPS. Algunos describen una situación imposible en la que no tienen permiso de trabajo pero no encuentran el dinero para solicitarlo sin él.

Esperamos, si Dios quiere, tener el dinero".

Fuera de una despensa de alimentos en Pilsen, docenas de personas hacen cola para la distribución de alimentos y ropa de la despensa. Algunos han atravesado la ciudad para conseguir alimentos, pasando más de una hora en autobús para llegar hasta allí. El aire frío se cuela por la fila, arrastrando el bullicio de las voces a lo largo de la manzana, mientras la gente espera a que se abran las puertas de la despensa.

Muchos de los que están en la cola son inmigrantes venezolanos y, como Gacias, han tenido dificultades para encontrar trabajo en Estados Unidos sin permiso de trabajo.

"Ha sido muy duro porque mi marido es el único que trabaja", dijo a Borderless Nasareth H.**, de 28 años, mientras esperaba en la cola con su hijo pequeño. "No he podido encontrar trabajo. Es muy, muy difícil. No encuentro trabajo en un restaurante ni en ningún sitio. Nada".

Dijo que una organización comunitaria venezolana se ofreció a ayudar a su familia a solicitar el TPS, pero calculó que el coste sería de casi $2.000 para cubrir a Nasareth, su marido y sus tres hijos. Después de pagar el alquiler, la familia ahorra lo que puede para la tasa de solicitud.

"Esperamos, si Dios quiere, tener el dinero en dos meses", dijo Nasareth.

Al igual que Nasareth, otros migrantes venezolanos dijeron a Borderless que las tasas de solicitud hacían imposible presentar la solicitud. Un migrante dijo que su familia estaba esperando a ver el resultado de su solicitud de asilo antes de decidir si solicitar el TPS.

Existe una solicitud de exención de las tasas de solicitud del TPS, pero consiste en un proceso separado de la solicitud del TPS y más tiempos de espera, dijo Lisa Koop, directora de servicios legales del Centro Nacional de Justicia para Inmigrantes.

"La gente ha estado viviendo en el limbo", dijo Koop. "La gente ha estado viviendo sin mucha seguridad, y la gente ha estado viviendo sin un camino claro hacia adelante".

Lo que se ve es desesperación

La mayoría de los inmigrantes rellenan la solicitud con la ayuda de un amigo o de organizaciones comunitarias locales que ofrecen asesoramiento jurídico gratuito, ya que puede resultar difícil rellenar la solicitud por sí solos para quienes no hablan inglés. La solicitud también requiere un acceso fiable a Internet, una impresora para los documentos y un escáner para cargarlos.

Centro Romero, una organización de servicios para refugiados e inmigrantes en el noreste de Chicago, ofrece servicios legales a inmigrantes, ayudando a muchos de ellos a solicitar programas como el TPS. La organización está desbordada por las necesidades de los miles de inmigrantes recién llegados a Chicago, dijo Diego Samayoa, director asociado del Centro Romero.

Muchos de los inmigrantes pueden no saber dónde buscar ayuda en primer lugar, explicó Samayoa, o que son elegibles para solicitar programas como el TPS, que son vías esenciales para vivir y trabajar en Estados Unidos.

"El TPS es una solución que permite [a los inmigrantes] dormir por la noche sabiendo que no pueden ser deportados", dijo Samayoa.

Por parte federal, había más de 200.000 solicitudes de TPS que están siendo procesados en todo el país por el Servicio de Ciudadanía e Inmigración de Estados Unidos (USCIS) a partir del 31 de marzo de 2023 - un total que no incluye a los miles de inmigrantes que actualmente están presentando solicitudes de TPS después de que Venezuela fuera rediseñada para el estatus hace dos meses.

Samayoa dice que ha visto solicitudes que tardan entre dos y seis meses en tramitarse. De acuerdo con USCIS, el tiempo medio que tomó para proceso solicitudes de TPS en 2023 fue de aproximadamente 12 meses.

Samayoa recuerda cuando ayudó a una familia en el departamento de inmigración legal del Centro Romero y conoció a su hijo pequeño, que entonces sólo tenía dos o tres años. Al ver la planta junto a un escritorio, el niño hambriento empezó a comerse las hojas verdes de la planta y la arena de la maceta.

La familia había atravesado la brecha del Darién para llegar a Estados Unidos, recorriendo 100 km a través de pantanos, montañas y bosques tropicales en la selva entre Panamá y Colombia. El niño, según Samayoa, se había acostumbrado a comer plantas durante el viaje a EE.UU., porque no había nada más que comer.

"En la mayoría de los casos, lo que se ve es desesperación", dijo Samayoa. "Ellos sí quieren trabajar, y sí quieren poner pan en la mesa aportando valor a la comunidad...[Pero para] alguien que lleva meses aquí, y saben que no pueden trabajar legalmente en EE.UU., ¿qué haces para sobrevivir?".

Una solución más amplia para los permisos de trabajo

Los defensores de la política han estado presionando para que se amplíen los permisos de trabajo a más inmigrantes fuera del programa TPS y trabajando por soluciones más permanentes para quienes desean trabajar legalmente.

El concejal de Chicago Jessie Fuentes (26º) ha impulsado un resolución que, de ser aprobada por el Ayuntamiento, pediría al gobierno de Biden que expidiera permisos de trabajo a los inmigrantes recién llegados, así como a los residentes indocumentados que llevan más tiempo viviendo en Estados Unidos, para que puedan trabajar legalmente aquí. La resolución, que cuenta con el apoyo de muchas asociaciones empresariales y organizaciones de inmigrantes, fue aprobada por el comité de inmigración del ayuntamiento el pasado jueves y podría someterse a votación en el pleno esta semana.

En la parte de comentarios públicos de la reunión del comité de inmigración, el presidente de la Asociación de Restaurantes de Illinois, Sam Toia, habló de las luchas del sector por la grave escasez de mano de obra, que afecta drásticamente a todos los restaurantes debido a que el Congreso "no ha resuelto nuestros problemas de inmigración".

"La solución a este problema ya está aquí", dijo Toia. "Millones de inmigrantes e indocumentados de larga duración están aquí, dispuestos a trabajar. Pero necesitamos que el gobierno lo haga posible".

Para Gacias, poder trabajar no sólo significaría poder mantenerse en Estados Unidos, sino también mantener a su madre en Venezuela, que necesita dinero para medicinas, y a su esposa e hijos.

"Me duele no estar junto a ella", dijo Gacias sobre su madre. "Lo he perdido todo".

A pesar de la incertidumbre de su solicitud de TPS y de las dificultades a las que se enfrentó al presentarla, Gacias piensa en aquellos que son menos afortunados que él, y que tal vez ni siquiera puedan presentar la solicitud en primer lugar.

Gacias tiene una dirección porque está viviendo con un amigo, por ejemplo, pero las personas que no tienen una dirección permanente no pueden solicitar el TPS porque los solicitantes necesitan una prueba de residencia y una dirección postal para recibir actualizaciones sobre sus solicitudes.

"Esto tiene que ser para todos, no sólo para una persona", dijo Gacias. "Seas venezolano o mexicano, seas lo que seas, debes ser respetado".

"Esto tiene que ser para todos, no sólo para una persona", dijo Gacias. "Seas venezolano o mexicano, seas lo que seas, debes ser respetado".

Mientras espera a saber si recibirá un permiso de trabajo y el TPS, Gacias pasa sus días retribuyendo a la comunidad, trabajando como voluntario en despensas de alimentos y colaborando con organizaciones de ayuda mutua para distribuir alimentos y otras donaciones a otros inmigrantes.

Dice que pensar en su madre en Venezuela, en todo lo que ha sacrificado para llegar hasta aquí y en quienes le han ayudado en Chicago le han hecho seguir adelante. Ahora quiere ayudar a otros inmigrantes como él, que empezaron viviendo en albergues y en la calle.

"Lo que me motiva es la gente de la comunidad", afirma Gacias. "Si no fuera por ellos, ya habría vuelto".

*Moises Gacias optó por utilizar un seudónimo para proteger su seguridad y privacidad.

**Nasareth H. prefirió no utilizar su nombre completo para proteger su seguridad y privacidad.