Tras 25 años viviendo en Estados Unidos, Aram Han Sifuentes solicitó la nacionalidad esta semana.

Después de vivir en Estados Unidos durante 25 años, Aram Han Sifuentes solicitó la ciudadanía esta semana. Sifuentes dice que está un poco triste por desprenderse de su ciudadanía surcoreana y renunciar a cosas como la sanidad universal, pero teme por su seguridad y su trabajo como artista bajo la presidencia de Donald Trump.

En los últimos años, Sifuentes ha defendido firmemente a los inmigrantes en su obra artística a través de proyectos como su Muestrario de pruebas de ciudadanía de EE.UU. y Biblioteca de préstamo de pancartas de protesta. Gran parte de su obra se inspira en la lucha de sus padres como nuevos inmigrantes y en la numerosa población latina indocumentada que la rodeaba de niña.

Borderless se sentó con Sifuentes en su estudio público en el Centro Cultural de Chicago para hablar de su obra.

Tenía cinco años cuando llegamos a Estados Unidos en 1992. Mi familia se trasladó al Valle Central de California, donde vivía mi tía. En realidad, el plan era ir a Los Ángeles. Pero justo después de llegar aquí se produjeron los disturbios de Los Ángeles y muchos negocios coreanos fueron atacados. Así que nos quedamos aquí.

Venir de Seúl, que es tan activa y tiene rascacielos por todas partes, a estar en el campo en California fue bastante raro. Mi familia me dijo que dejé de hablar durante un año. Ni coreano ni inglés. Estaba muy confusa intentando entenderlo todo.

Más del 50% de la población del Valle Central es latina y mucha gente está indocumentada, porque son trabajadores agrícolas emigrantes. Como crecí en un lugar así y era inmigrante, siempre fui consciente del problema de la inmigración. Así que me licencié en la Universidad de Berkeley y estudié estudios latinoamericanos, centrándome en la política de inmigración. Pensé que iba a ser veterinaria o abogada de inmigración, pero allí me enamoré del arte.

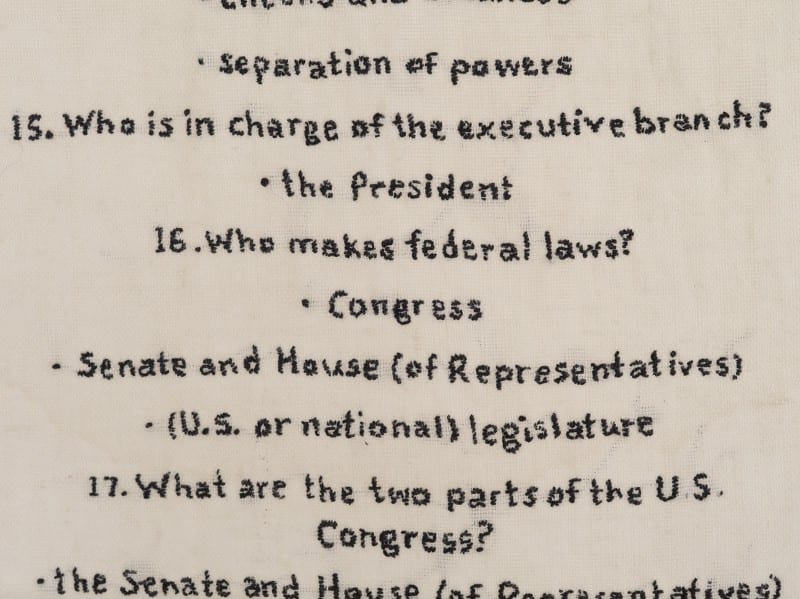

En mi trabajo actual intento complicar y profundizar la comprensión de la experiencia del inmigrante. Así, con mi proyecto U.S. Citizenship Sampler, coso las preguntas del examen de ciudadanía. Destaco lo difícil que es el examen y lo discriminatorio que es el lenguaje contra los inmigrantes. Que tenemos que aprender estas preguntas realmente estúpidas que los ciudadanos nunca necesitarían saber. ¿Como quién fue presidente durante la Primera Guerra Mundial? ¿Por qué eso me va a convertir en un buen ciudadano si lo sé?

Hago talleres con los muestreadores en los que voy a grupos de no ciudadanos que ya se están reuniendo, a menudo como grupos de padres en colegios. Voy cada semana durante dos meses o así y hablamos del examen y de lo injusto que es. También compartimos recursos y estudiamos juntos, y hacemos estos muestrarios que están a la venta por el coste de solicitar la ciudadanía - $725. Así podemos vender estos muestrarios y quien los haga puede utilizar el dinero para el examen o para lo que necesite. Muchos de mis participantes son indocumentados y tienen un montón de gastos legales.

Ahora tenemos cien muestrarios y he vendido diez. Antes, los que se vendían eran los que eran más decorativos, pero ahora he estado presionando para vender los de la gente que tiene más necesidad con Trump y usarlos para hablar de lo precario que es ser no ciudadano, aunque seas residente legal. Especialmente ahora, vemos que con la prohibición de viajar que incluso con su tarjeta verde no importaba. Solo tienes ciertos derechos como ciudadano.

Sigo sin tener la ciudadanía. Iba a esperar a terminar mi sampler para solicitar la ciudadanía, pero me asusté después de Trump. Especialmente haciendo trabajo político, solo quiero ser más confrontativa y no temer las consecuencias. Y tengo que preocuparme por mi hija, mi "bebé ancla". Así que con eso, me asusté. Sabía que esta persona estaba interesada en comprarlo, así que le pregunté si lo compraría sin que estuviera completo. Y me dijeron que sí.

La gente me dice que su trabajo es muy oportuno. Pero yo pregunto: ¿cuándo no es oportuna la inmigración? ¿Cuándo estas cuestiones no son un gran problema? Con Trump, creo que la gente es más consciente de lo que está pasando y está más presente. Hay más urgencia y conciencia. Espero que las cosas hayan empeorado para que mejoren, para que la gente se movilice y exija que ocurran cosas mejores.

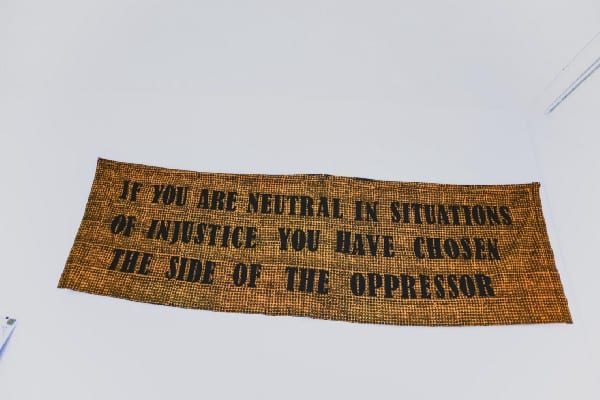

Decidí crear la Biblioteca de Préstamo de Pancartas de Protesta justo después de las elecciones. Es una especie de espacio de trabajo en el que hacemos pancartas constantemente, pero otras personas vienen y pueden aprender a hacer sus propias pancartas y nosotros les proporcionamos todos los materiales. Se tarda entre una hora y media y dos horas. Así que la gente viene y hace sus propias pancartas. Para mí, lo más importante es que se usen, así que les digo que si van a usarlos, que se los lleven. Pero si quieres que los use otra gente, puedes donarlo a la biblioteca.

Ahora mismo tenemos más de 110 pancartas. Y tenemos unas 50 en préstamo. La mayoría se utilizan en protestas, pero también en producciones teatrales y algunos profesores las han cogido para colocarlas en sus aulas como parte de sus clases. Algunas personas las cogen y las colocan en sus lugares de trabajo o en sus casas.

La razón por la que es una biblioteca es que quería crear un espacio para las personas que no se sienten cómodas yendo a las protestas. Creo que yo tengo un poco más de miedo porque lo tengo delante de la cara y sé que deportan a la gente, a los residentes legales por cosas sin importancia. Incluso por ser detenidos en protestas. Así que tengo miedo de eso y, por supuesto, siendo una madre primeriza, no me siento cómoda yendo a protestas y llevando a mi hija, porque nunca sabes lo que va a pasar. Por eso acabó convirtiéndose en una biblioteca. De ese modo, las pancartas podían seguir utilizándose. No tenemos que quedarnos callados. Podemos seguir participando de esta manera.

A veces me deprimo y creo que el futuro es realmente sombrío. Pero espero que luchando y resistiendo a Trump nos superemos. He estado leyendo que las ventas de material artístico han subido porque la gente está haciendo sus propias pancartas y participando activamente en las protestas. Ese tipo de cosas realmente me hacen seguir adelante. Hay mucha gente a la que le importa y que está haciendo algo al respecto.

Tenemos que resistir juntos y protegernos y querernos, porque que le den a Trump.

La biblioteca de préstamo de pancartas de protesta de Sifuentes estará en el Centro Cultural de Chicago hasta el 17 de mayo. Después de esa fecha, las personas que deseen contribuir a la biblioteca o tomarla prestada pueden hacerlo poniéndose en contacto con Sifuentes en Facebook.