Max Herman/Borderless Magazine

Max Herman/Borderless MagazineWhile the Trump administration uses tattoos to target and deport Latino immigrants, these artists are tapping into Chicano tattooing’s origins to resist and uplift their community.

Brian Nazario was 9 years old when he tattooed for the first time.

With his mom’s sewing kit, he and his friends poked designs of small crosses, praying hands and neighborhood names on themselves. He says these symbols, alongside graffiti and music, represent his corner of Albany Park — a neighborhood in Chicago’s Northwest Side where almost half of all residents are Hispanic or Latino.

“All of these people around me in my neighborhood, in my barrio, were just hungry to wear these things that were close to them,” Nazario said.

News that puts power under the spotlight and communities at the center.

Sign up for our free newsletter and get updates twice a week.

In recent months, President Donald Trump’s administration has used tattoos as a broad indicator of gang involvement, justifying the detention and deportation of Latino immigrants nationwide. However, this has fueled a renewed sense of pride in Nazario’s work and that of other Chicano, or Mexican American, tattoo artists in Chicago as they use their skills to push back on false narratives criminalizing Latino immigrants.

These Chicano tattoo artists have been fundraising for immigrant rights, supporting mutual aid efforts and sharing political messages while evolving their skills to keep their passion for tattooing alive.

“The fear of being targeted is real, but so is pride,” Nazario said. “Having so much pride that it develops into bravery.”

Using tattoos to criminalize Latinos

Since January, the Trump administration has focused its agenda on the mass deportation and detention of immigrants and noncitizens, disproportionately impacting Latino communities.

Department of Homeland Security (DHS) officials have openly argued in favor of using racial profiling to make arrests. In California, the Supreme Court green-lit Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) agents targeting suspects based primarily on apparent race or ethnicity, whether they have an accent, the type of work they do, and presence at locations such as car washes or agricultural sites.

“The Government … has all but declared that all Latinos, U.S. citizens or not, who work low wage jobs are fair game to be seized at any time,” Supreme Court Justice Sonia Sotomayor wrote in her dissent of the decision.

Last month, Gregory Bovino, commander-at-large of the U.S. Border Patrol, told WBEZ that agents under his watch have arrested people based partly on “how they look.”

Tattoos have become one of the characteristics that agents take into account when considering a person’s appearance, with federal immigration authorities arguing that some tattoos indicate criminal ties to groups such as the Venezuelan Tren de Aragua gang. Law enforcement experts told the New York Times that tattoos alone are not sufficient to prove someone is a member of a criminal group.

Read More of Our Coverage

For some Venezuelan men with no known criminal records or gang affiliations, tattoos of crowns over the words “mom” and “dad” and a pocket watch became the justification for their alleged Tren de Aragua ties. The men were then deported to El Salvador’s mega-prison under the Alien Enemies Act, CBS reported.

Earlier this year, Kilmar Abrego Garcia, a man from El Salvador who lived in Maryland for more than a decade, was illegally deported to El Salvador. DHS claimed his finger tattoos reflected ties to the MS-13 gang, despite gang experts telling CNN that Abrego Garcia’s tattoos had “nothing” that was “definitively gang representative.”

This week, a fired Department of Justice lawyer overseeing immigration cases said he was told to lie about Abrego Garcia’s criminal history and to argue that he was an MS-13 member to prevent his return to the United States. The lawyer, Erez Reuveni, was fired after refusing to sign a brief falsely calling Abrego Garcia a terrorist, according to CBS News.

The U.S. justice system has long used tattoos to designate people — often Black and Latino men and youth — as gang members, according to research by Southwestern Law School professor Beth Caldwell.

“Aztec or Mayan symbols depicting people’s ancestral roots, words or numbers representing places in Mexico or other Latin American countries, religious symbols … are some examples of tattoo art that has been used to define people as gang members [by law enforcement],” Caldwell wrote. “But these symbols are not uniquely used to demonstrate gang membership; rather, they are more broadly characteristic of Chicano identity.”

The art and history of the Chicano tattoo

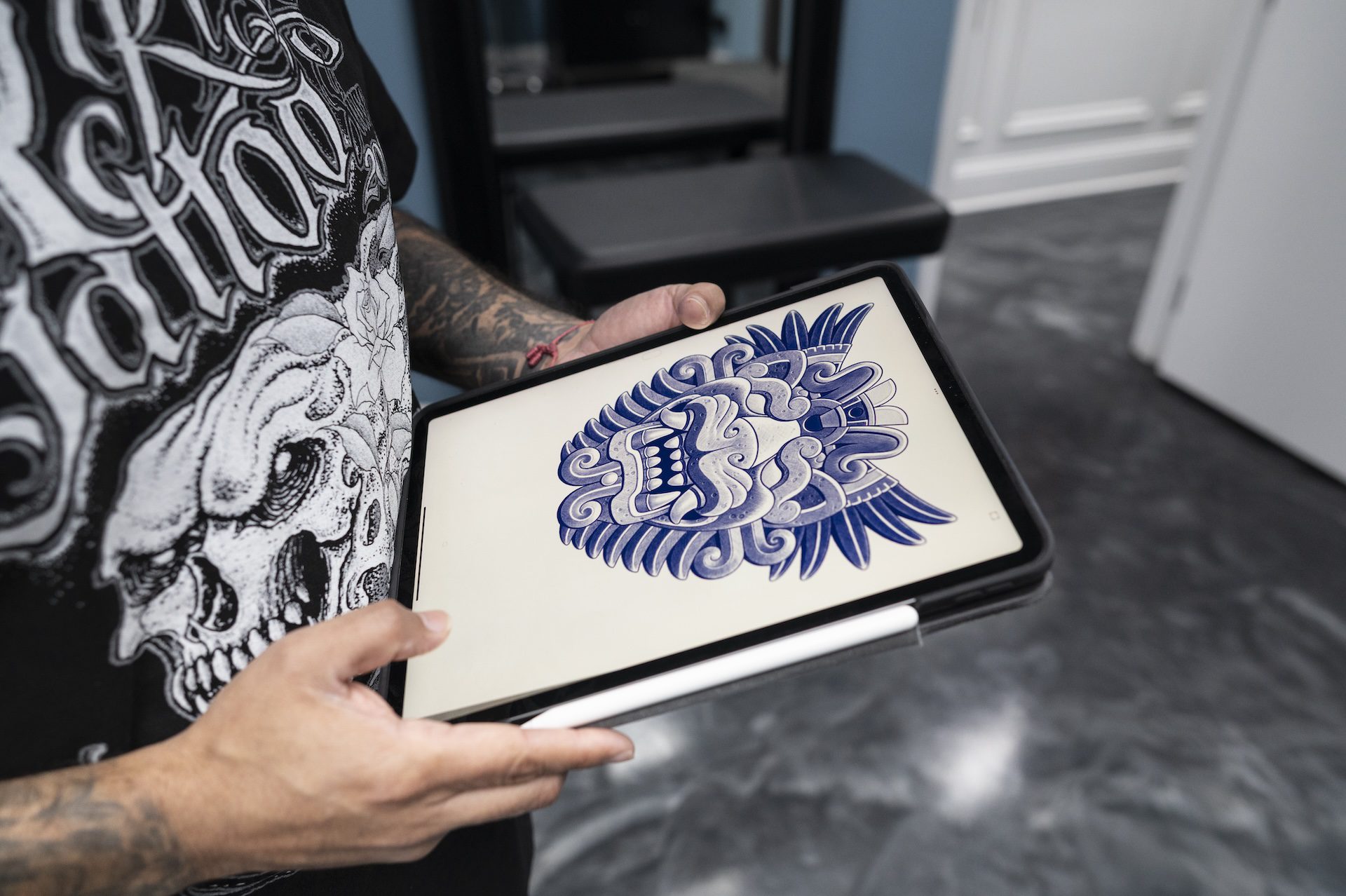

Tony Carrillo, a Chicano-style tattoo artist known as “Tony Uno” with over two decades of professional tattooing experience, said his tattoos are a form of pride in his identity as the son of first-generation immigrants from Zacatecas, Mexico.

Most of Carrillo’s early tattoos were in the Chicano style: black-and-gray tattooing that features Mexican symbols, religious icons, Old English lettering, lowriders, and Mexican revolutionaries.

The images he tattooed on himself and his friends in his teens reflected the street life he was a part of at the time, said Carrillo, who was born and raised in Pilsen.

“We were looking for an identity,” Carrillo said. “As Mexican Americans, or Chicanos, we are sometimes seen as not Mexican enough. We’re also not fully accepted as Americans, so we found the streets as our comfort.’”

Incarcerated Mexican Americans in the California prison system created Chicano-style tattoos in the late 20th century. They used self-assembled tools and homemade black ink to tattoo themselves, making the photorealistic style now known as black-and-gray.

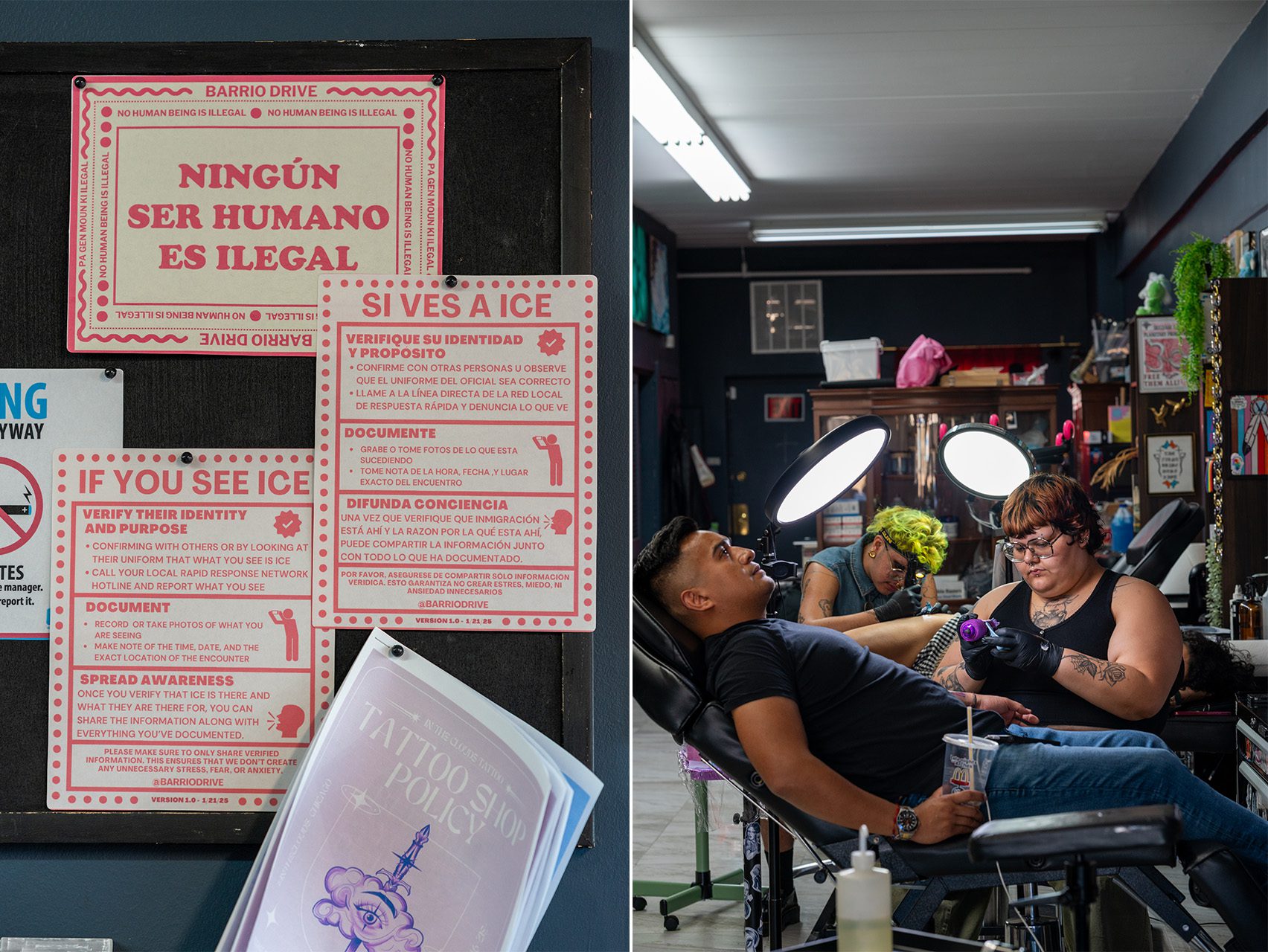

Victoria Aguirre, a Chicana tattoo artist at In The Clouds tattoo shop, said the Chicano style is tied directly to how Latino communities have been disproportionately criminalized and impacted by the U.S. prison and justice systems.

“The reasons why these people were imprisoned is hugely because of their identities as Chicanos,” Aguirre, also known as “V Inks,” said. “Mexican Americans were not being considered American and were being criminalized for it.”

In the 1970s and 80s, people of color were disproportionately incarcerated and targeted as the federal government cracked down on President Richard Nixon’s “war on drugs” and as the U.S. prison population nearly doubled from 329,000 to 627,000 under President Ronald Reagan.

Under these conditions, tattooing became a way for incarcerated Latinos to practice greater autonomy over their own bodies — documenting their experiences and “micro-histories” by creating a new tattooing style, Aguirre said.

“They can be stripped of literally everything in prison but their identity and these symbols of their identities,” they said.

As tattooing became more normalized in the mainstream with shows like Miami Ink in the 2000s, the black-and-gray style also grew in popularity, with celebrities like David Beckham, Adam Levine and Justin Bieber sporting Chicano tattoos.

“The images are just beautiful in their own world,” Carrillo said. “I think they speak to everybody.”

Putting art to action

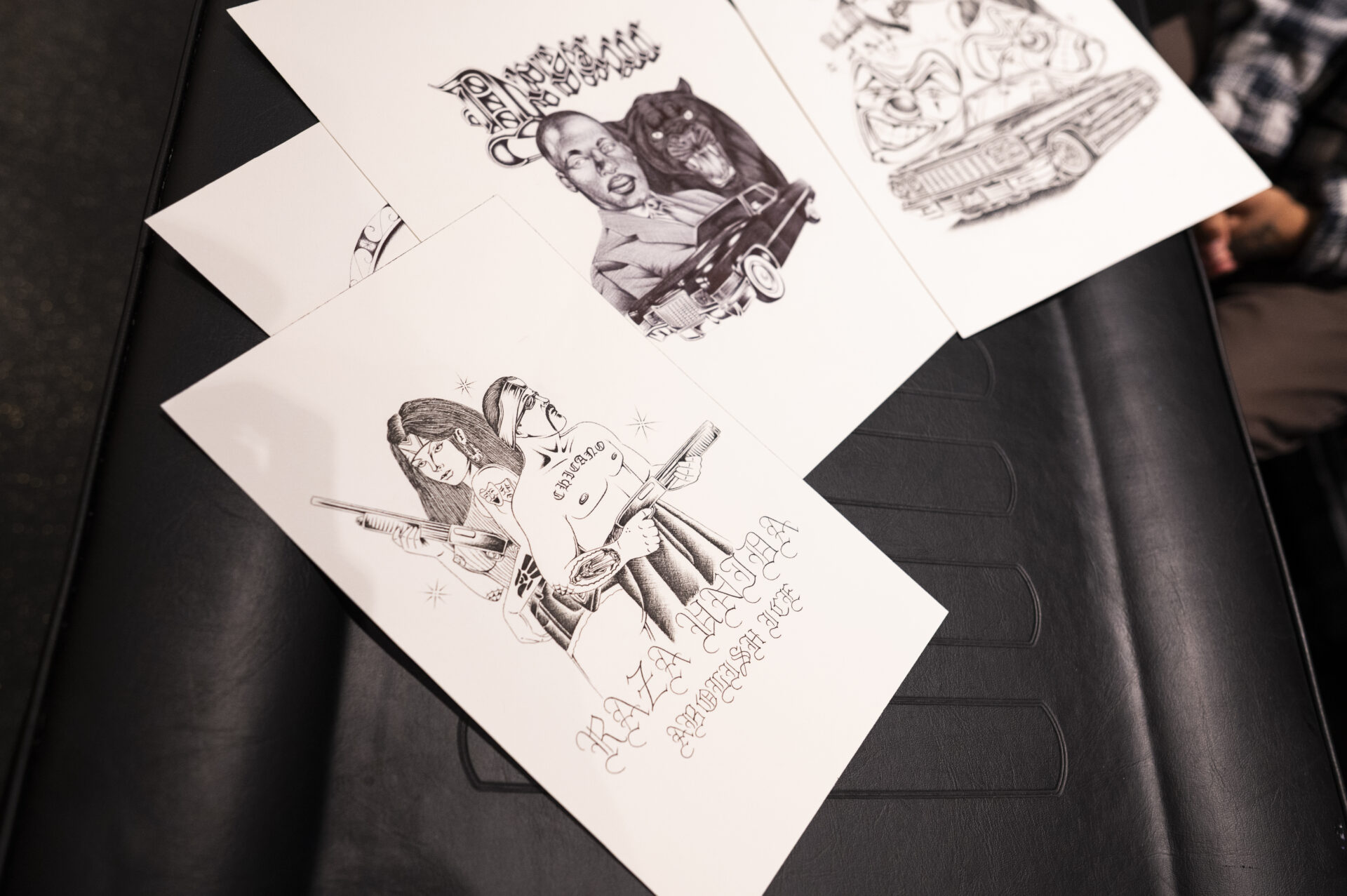

Inside the Family Tattoo shop in West Lakeview, Nazario’s Chicano designs line the walls of his station. Almost a decade into his career, Nazario says he’s honored to be in a position where he’s tattooing people from different walks of life.

But even though his craft is more widely available now, some designs aren’t for sale.

Hidden in a drawer at his station, one design features a Mexican man and woman above text that reads, “Abolish ICE.” Another shows ice cubes melting, while another is of Martin Luther King Jr. next to a black panther.

Nazario has used his art and tattoo design skills to create these pieces for various causes, including a fundraiser that donated proceeds to the Illinois Coalition for Immigrant and Refugee Rights (ICIRR).

Doing something tangible to help his community as an artist is important, Nazario said, because having pride in identity without action won’t bring change.

“Now more than ever, it’s been revealed to me that out of everything, Chicanismo, being Chicano, means just being there to serve your community,” Nazario said. “I’m no one with resources that other people don’t have. I’m just a regular person who uses my hands and creates art. But amongst all of that, I’m still able to help the community.”

That’s a sentiment that resonates across tattoo artists in the city.

At In The Clouds tattoo shop on the Far Southwest Side, Aguirre and other tattoo artists host fundraisers for transgender, women’s and immigrant rights. A recent fundraiser, Aguirre said, raised almost $1,000 to support GoFundMes for immigrants’ legal services.

For Mexican Independence Day, Aguirre and colleagues at In the Clouds created flash, or pre-drawn, designs featuring Mexican gun girls, Aztec warriors and messages such as “F— ICE” and “La revolución no será televisada” — “The revolution will not be televised.”

As Aguirre has referenced flash from the ‘70s and ‘80s to reflect on the incarceration of Latinos at the time, they said they hope their flash can be looked at by future artists in a similar way: through the lens of their experiences and modern history. Flash tattoos are often direct responses to the historical contexts they were designed in, Aguirre said.

“History continues to repeat itself,” they said. “You can’t rely on what racism and discrimination looked like in the ‘60s and be like … ‘it’s not happening.’ It’s still happening.”

Redefining Chicano

Alongside using their art for important causes, these tattooers are pushing the Chicano style forward, maintaining their passion for their craft while expanding the Chicano tattooing community.

Aguirre said they like incorporating more feminine symbols, such as Mexican gun girls, into their tattoo designs. Many early Chicano and American traditional tattoos were more masculine, Aguirre said, which pushed out female and queer artists and patrons.

“You can continue to do traditional Chicano pieces, and that’s always going to be super important,” Aguirre said. “But drawing people, especially people who identify as Chicano, as they are right now, living in the aesthetics and visually living as they do right now is super cool and super important … because it is all about this documentation of life and self.”

Seeing artists like Aguirre change and evolve the Chicano art style is something Carrillo hopes will continue as more talent joins Chicago’s Chicano tattooing community.

“They’re going to keep pushing the Chicano style even further,” Carrillo said. “That’s the plan, right? Each generation should do better than the next.”

Carrillo said his mindset and dedication to his craft stem from his parents, whose work in low-paying, physically demanding jobs laid the foundation for his current life and career.

“You could tell us that this is who you think we are. You could group us as criminals or whatever you want in the news, but that’s not who we are,” Carrillo said. “I’m going to show you that we have a rich history.”